Assessing the differences in the scale of nutrition response efforts to El Niño in Ethiopia

By Getinet Babu, Alexandra Rutishauser-Perera and Claudine Prudhon

Getinet Babu is a humanitarian nutritionist with over 12 years’ extensive international and national experience in the sector and is currently a nutrition advisor in the Humanitarian Surge Team with Save the Children UK.

Getinet Babu is a humanitarian nutritionist with over 12 years’ extensive international and national experience in the sector and is currently a nutrition advisor in the Humanitarian Surge Team with Save the Children UK.

Alexandra Rutishauser-Perera, has 11 years of experience in both humanitarian and development contexts and is currently the global humanitarian nutrition advisor with Save the Children UK.

Claudine Prudhon PhD is a researcher in humanitarian infant and young child feeding in emergencies with Save the Children UK.

Location: Ethiopia

What we know: Ethiopia suffered the worst droughts in decades in 2011 and in 2016, requiring nutrition emergency response.

What this article adds: Save the Children has compared the 2011 and 2016 nutrition responses. The severity of the drought was greater in 2016. The Government of Ethiopia led the humanitarian effort, supported by partners including UNICEF, WFP, OCHA, NGOs and donors. There was a significant improvement in the 2016 response compared to 2011 in terms of government leadership, programme coverage and quality of intervention. Humanitarian nutrition partners’ commitment to the country humanitarian coordination mechanism was strong. There was greater nutrition staff capacity in-country, a reflection of capacity-building since 2011. As a result, more children were screened in 2016 (13 million) compared to 2011 (3.3 million) and the nutrition response reinforced existing community systems, rather than taking the form of direct implementation. Persisting challenges include capacity limitations at multiple levels, reporting and referral pathways between sectors, and the need for a more comprehensive nutrition response.

Context

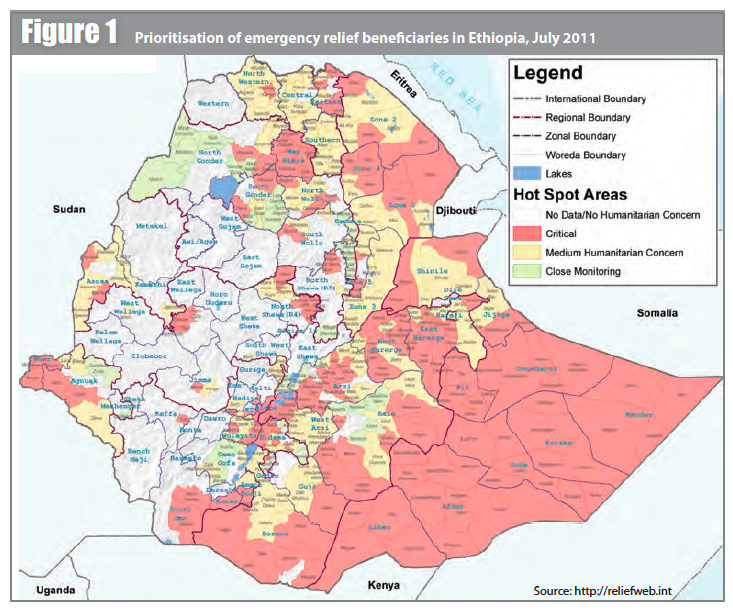

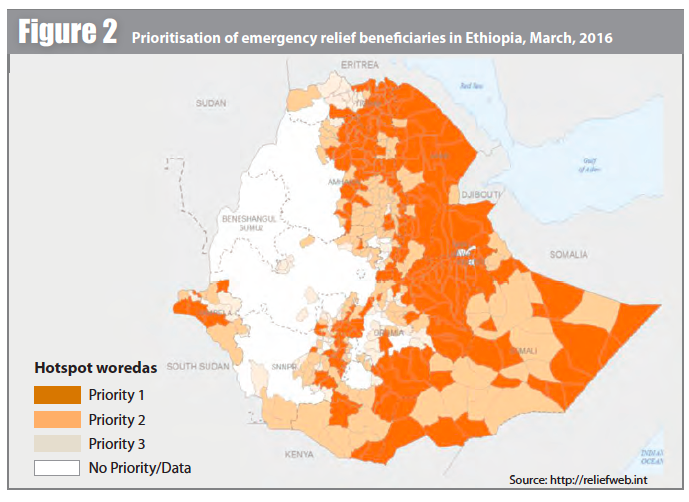

In Ethiopia 80% of the population relies on rain-fed agriculture or pastoralism. In 2015-16, the country experienced one of the worst droughts in decades, driven by El Niño; eastern areas were particularly affected (see Figure 1). The most recent previous drought was in 2011, when two consecutive seasonal rains failed, impacting the southern, eastern and north-eastern parts of the country (Somali, Afar, East and Southern Tigray, Southern Oromia and SNNPR) (see Figure 2). This article compares and contrasts the nutrition response to the droughts.

Projected needs

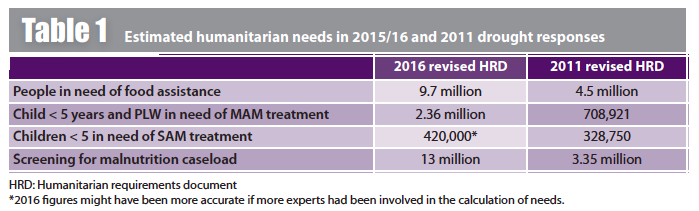

In the 2015-16 response, estimates of those in need of urgent food assistance rose from 2.9 million in January 2015 to 9.7 million (10% of the total population) in August 2016. An additional eight million people were benefitting from the Productive Safety Net Programme (cash and food support). Projected acute malnutrition caseloads for under-fives and pregnant and lactating women were higher than previous years, including the 2011 drought year, and expected to rise (see Table 1).

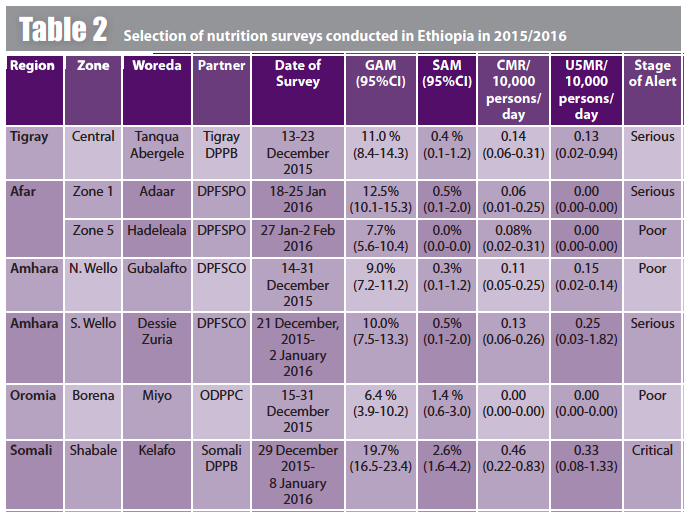

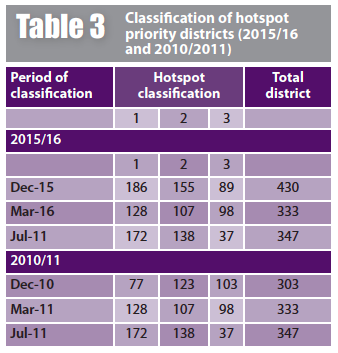

Twenty-one biannual standard nutrition surveys (BANs) were conducted between December 2015 and January 2016 (Afar, Amhara, Tigray, SNNPR and Oromia regions). Of the four classifications used to describe the nutrition situation, two out of 21 surveys were classified “critical”; four “serious”; 11 “poor”; and four “normal” or “typical” (see Table 2 for a selection of survey results). In addition, Ethiopia has an established early warning system, involving “hotspot” nutrition and food security data collection and classification systems, similar to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC). In July 2016, a total of 420 hotspot priority 1 to priority 3 districts were identified, compared to 347 in June 2011 (see Table 3 for 2016 breakdown).

Modalities of the 2016 response

Coordination

The Government of Ethiopia led the humanitarian response, supported by partners including UNICEF, WFP, OCHA, NGOs and donors. The Government activated the Multi-Agency Coordination (MAC) and Incidence Command Systems (ICS) taskforce, which was expanded to include representation from humanitarian and donor partners. The MAC provides strategic guidance and coordinates response at national level. The ICS facilitates and coordinates response at regional and zonal levels. Sector efforts are coordinated by taskforces established in each line ministry. For example, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) assistance is coordinated by the Ministry of Water, with support from UNICEF through the WASH Emergency Task Force (ETF)/WASH Cluster. Health and nutrition assistance is coordinated by the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) with support from the Health and Nutrition Taskforce and ENCU).

The 2015-16 response reflected lessons learned from the 2011 response, with new or improved systems in place. Key elements of the 2015-16 response included:

Treatment of severe acute malnutrition (SAM): Community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) services are delivered through the Health Extension Programme to treat severe acute malnutrition (SAM). Escalation in caseload beyond capacity of health facilities was met by scale-up of supportive interventions, involving training, quality assurance (supervision), human resource management and strong coordination with the district-level health department. (For an example of such scale-up, see field article by GOAL in this edition of Field Exchange).

Logistics support to improve access to therapeutic food, drugs and medical supplies: Supplies of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) to cover 75% of estimated need and F-75 and F-100 therapeutic milk and medications were supplied by UNICEF and the zonal/district health offices. Nutrition partners provided logistic support and additional supplies as needed. During the first half of 2016, 194,892 cartons of RUTF were dispatched to the regions.

Strengthening of referral systems linking services to communities: Nutrition-sector partners supported hospitals, health centres, health posts and mobile health and nutrition teams (MHNTs) and strengthened referral systems between outpatient therapeutic programmes (OTPs), stabilisation centres (SCs) and community screening points. Vitamin A supplementation (VAS) was combined with screening and referral of malnourished children. Treatment facilities expanded; as of September 2016, SAM services were available at 14,903 OTPs and 1,527 SCs, as well as 49 MHNTs nationally.

Screening: Since 2012, the FMOH has implemented Child Health Days (CHDs), a joint programme supported by UNICEF and WFP. District-level health office and health extension workers implement quarterly campaigns of VAS and deworming and nutrition screening of all under-fives and pregnant and lactating women (PLW), with referral as necessary. The CHD mechanism was used as the screening/referral mechanism through 2015 and the first quarter of 2016. At the start of the second quarter, the Government agreed to increase screening by health extension workers (HEWs) to a monthly schedule in all priority 1 districts in Amhara, SNNPR, Oromia, and Tigray regions to improve timely admission and reduce food-sharing at household level. In practice, capacity challenges in many districts, particularly Afar and Somali regions, delayed screening, hotspot classification and consequently response.

Management of moderate acute malnutrition (MAM): WFP supports the Disaster Risk Management and Food Security Sector (NDRMC) to deliver supplementary rations of corn-soya blend (CSB) and oil to MAM cases. In 2016, WFP was responsible for the provision of targeted supplementary food (TSF) rations for all priority 1 districts; rations were distributed through existing government systems. Since monthly screening began in Q2, delayed submission of information to WFP delayed WFP distribution of commodities to the affected population scheduled for the first quarter of the response and impacted on the formal release of the updated list of priority hotspot woredas by the Government. When released, the number of priority 1 districts had increased considerably, from 186 in December 2015 to 219 in March 2016.

Infant and young child feeding (IYCF): UNICEF and a number of nutrition agencies identified gaps in IYCF programming and in January 2016 UNICEF requested a technical rapid response team specialist on IYCF in emergencies (IYCF-E). Several tools were developed, including guidance for Mother-Baby Areas and Mother-to-Mother Support Groups, an IYCF-E curriculum module for HEWs, and an IYCF-E multi-sector integration document. A workshop was organised with several ENCU members, which oriented the development of a national IYCF-E workplan.

Beneficiaries reached in 2015/2016 response

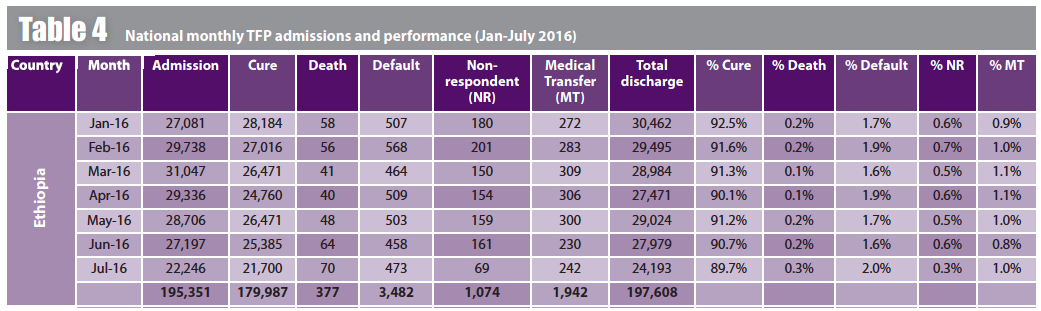

The nutrition situation and response was closely monitored by MOH/ENCU/ NDRMC in collaboration with nutrition partners using monthly TFP admissions, ad hoc surveys, updating hotspot woreda lists and examining nutrition responses. Analysis of these data indicated that the nutrition situation deteriorated considerably in most of the El Niño-affected districts of Somali, Afar, Amara, Oromia and SNNPR. A total of 195,351 SAM cases were admitted in over 14,568 TFP sites between January 2016 and July 2016 (88.6% reporting rate; see Table 4). This comprised 33,817 cases in SNNP; 88,270 in Oromia; 18,368 in Somali region; 29,086 in Amhara; 16,669 in Afar; 6,868 in Tigray; and 2,273 in other regions. By the end of the third quarter of 2016, the TSFP had reached 1,208,917 moderately malnourished children and 1,258,718 PLW.

Comparing actual and projected caseloads in the first semester 2016, the total TFP admissions between January to June 2016 was 173,105 (89.1 % reporting rate), 23.5% less than the projected caseload (226,400) for that period (Humanitarian Requirements Document (HRD), June 2016). The projection prevalence was estimated based on existing screening data (coverage above 80%) from the second round of 2015 screening data (July to December 2015) and taking into account hotspot classification. Taking into account the context, response and underlying causes of malnutrition from July-December 2015 and based on the projections for the future context and underlying causes of malnutrition, prevalence increased by a factor of 2. Incidence was estimated, based on historical programme data: MAM incidence of 1.6 and SAM incidence of 2.6. The actual SAM caseload was affected by seasonal variation in SAM admissions due to MAM treatment (most MAM cases was treated during the second and third quarter and contributed to less SAM caseloads). Some SAM admissions were not captured (89.1% reporting rate).

Key areas of difference between 2011 and 2016 responses

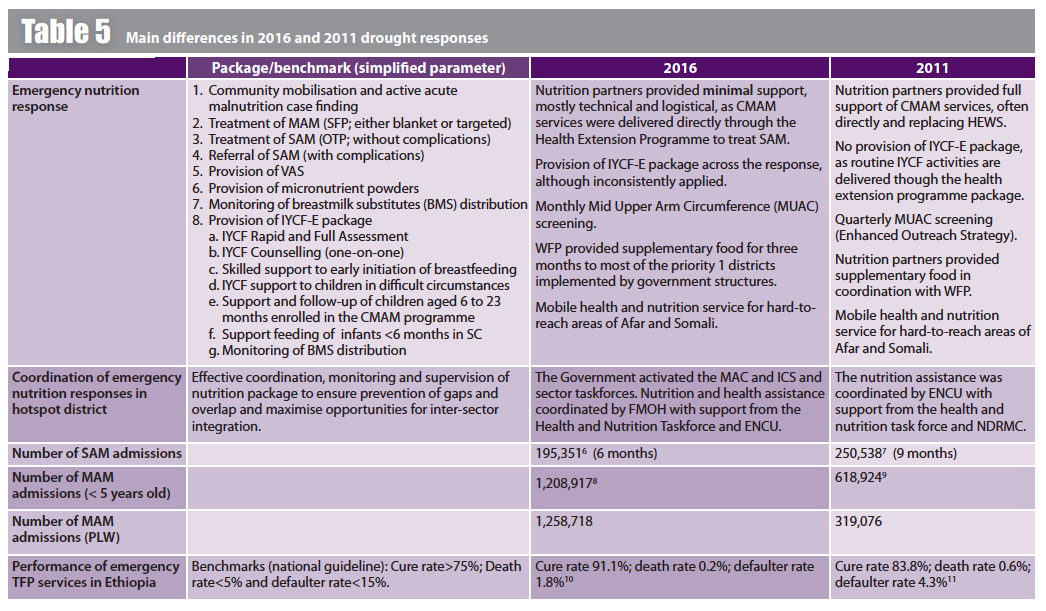

Table 5 outlines the distinguishing features between the 2011 and 2016 drought responses. In the 2016 response, there were more trained manpower/nutrition staff to focus on emergency nutrition. Recognition of community engagement as a key service delivery strategy was demonstrated by a strong community outreach support system, involving HEWs and health development armies (HDAs), who played a key role in implementation of government services. This is a reflection of capacity-building by FMOH and nutrition partners from 2011 onwards. As a result, many more children were screened in 2016 (13 million) compared to 2011 (3.3 million) and nutrition partners could respond by reinforcing existing community systems, rather than setting up new ones. Another important area of progress in the 2016 response was the inclusion of IYCF-E in the planning and emergency resource mobilisation and allocation. IYCF-E was also included in some priority response areas, although later than warranted. Government leadership and coordination was much stronger in 2016, and significant government resources were allocated; government provided over US$200 million of emergency support, including a first instalment of US$97 million to support food distribution in early 2016.

Challenges and lessons learned

Ethiopia has made steady progress over the last ten years, dramatically improving child and maternal mortality and making huge strides towards globally agreed targets. While drought increased the vulnerability of millions of people, the 2016 government-led response, with strong UN, NGO and donor support, ensured recovery in the hardest-hit communities and has helped build longer-term resilience of systems and people.

Resource shortfalls constrained humanitarian operations during the first half of 2016; in particular in Amhara, Oromia and Tigray regions that did not receive TSFP during quarter 1 due to commodity-distribution delays related to information delays. The growing food insecurity challenges necessitated urgent reinforcement of response efforts and scaling-up of operations by all actors, including mobilisation of additional resources.

One key intervention area was the service delivery mechanisms to provide treatment for SAM cases. Humanitarian partners supported health facilities, with HEWs providing the service. However, given the high caseload, nutrition partners could have considered a fuller provision of CMAM services, especially for priority 1 districts. This approach would have helped HEWs focus on routine activities and protect the community element of SAM treatment.

It is important that responses in hotspots do not focus solely on health facilities and that the emergency response is comprehensive; in both 2011 and 2016 most nutrition partners focused on treatment of severe malnutrition. Key future considerations include integration of emergency nutrition responses with WASH and health where needed; capacity-building of health staff and improvement of infrastructures for provision of TFP services; maximised and more timely IYCF-E support; strengthened monthly nutrition screening and expansion to the worst-affected Afar and Somali regions; and improved monitoring of the response with timely TFP reports and coordinated surveys.

Government and humanitarian actors should invest in clear reporting, referral and follow-up systems/pathways for cases of nutrition, health and child protection concern; there were gaps in household follow-up of such cases in the 2016 response. Additionally, capacity of the health and nutrition sector at regional, zonal and district levels, including the multi-sector emergency preparedness committees and the emergency rapid response teams, was not adequate and would have benefited from more technical support. For example, the emergency preparedness committees provide nutrition early warning information; however in some regions they did not report increased cases of malnutrition, related to capacity constraints. Continued capacity-strengthening is vital at all levels through training, development of guidelines, technical and financial support and provision of communications materials.

Donors and nutrition agencies were not always able to respond to the hotspot classification updates. The significant increase in priority 1 hotspots in early 2016 (from 186 to 219) came as agencies were still submitting proposals for the previous hotspot caseload. Intervention delays were partly due to the time taken for federal and state authority signatures of necessary regional MoUs. Irregular screening data submission to WFP led to late distribution of supplementary foods for eligible MAM cases, especially in Somali and Afar regions where capacity is particularly lacking. While changing distribution and screening modalities helped, operational and logistics constraints persisted in the face of an accelerated distribution schedule.

Although IYCF-E interventions were implemented in some high-priority districts, they were limited in scope and did not cover all priority districts due to late prioritisation of IYCF-E by donors and most agencies and lack of agency expertise. IYCF-E interventions were not successfully integrated into OTPs. Development of a minimum response package tool by the NTWG, to harmonise IYCF-E with CMAM programming and other sectors such as child protection would have helped. For future preparedness, it will be vital to organize nationwide IYCF-E trainings to improve the capacity of governments, UN agencies and NGOs.

Conclusion

Responding to the nutritional needs of an emergency-affected population requires a commitment to a coordinated and collaborative approach among a collective of key actors. There was a significant improvement in the 2016 response compared to 2011 in terms of government leadership, national response, and coverage and quality of interventions. Humanitarian nutrition partners’ commitment to the country humanitarian coordination mechanism was excellent. Most actions were aligned with agreed priorities, used shared expertise and ensured that the nutrition response was based on sound and informed decision-making. This helped avoid or resolve gaps and duplication. Despite considerable progress, challenges remained. The 2016 response benefitted greatly from lessons learned and subsequent actions taken post-2011 drought; lessons from 2016 should inform preparedness and future response.

For more information, contact: Getinet Babu, email: g.babu@savethechildren.org.uk