A journey to multi-sector nutrition programming in Nepal: evolution, processes and way forward

By Pradiumna Dahal, Anirudra Sharma and Stanley Chitekwe

Pradiumna Dahal is a nutrition specialist with UNICEF Nepal and has more than 15 years’ experience in public health, nutrition and food security. Having helped formulate major nutrition policies, plans and strategies in Nepal, he is one of the core experts supporting the National Planning Commission of the Government of Nepal to develop the Multi-Sector Nutrition Plan (MSNP). He is actively engaged in scaling up nutrition in Nepal.

Anirudra Sharma has worked as a nutrition specialist with UNICEF for 17 years, including as emergency nutrition cluster coordinator for the last six years. He has more than three decades experience with the Government of Nepal, Save the Children and UNICEF. His scope of work has included formulation of national nutrition and health policies, plans and strategy; national programme design on integrated management of acute malnutrition (IMAM); and disaster risk reduction. He is a core expert team member supporting the National Planning Commission in the MSNP development.

Stanley Chitekwe is the Chief of Nutrition for UNICEF Nepal. He has worked for more than 17 years with UNICEF in Africa and now in South Asia. His vision is to treat acute malnutrition and eradicate stunting. He is a mentor to many young professionals. His focus is on evidence-based, cost-effective programme delivery and using innovations.

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Planning Commission, Ministry of Health and other sector ministries of the MSNP (Education; Women, Children and Social Welfare; Agriculture, Livestock and Birds; Water and Sanitation; and Federal Affairs and Local Development). The authors also sincerely thank the European Union for their generous support to UNICEF for scaling up MSNP in Nepal, as well as the contributions from other UN agencies and nutrition stakeholders, mainly USAID/Suaahara and World Bank, in rolling out the MSNP in Nepal.

Location: Nepal

What we know: Multi-sector policies and plans are an increasing feature of country efforts to tackle undernutrition.

What this article adds: In 2012, Nepal developed a Multi-Sector Nutrition Plan (MSNP I), a reflection of 30 years of policy evolution. Rollout included restructure and development of national and district/village level coordination and steering committees, technical working groups and pilots in selected districts. Subsequent scale-up was informed by lessons learned. Since MSNP I, resourcing for nutrition-sensitive programming has significantly increased. Stunting prevalence has fallen from 57% (2001) to 37% (2014); an annual rate of reduction of 3.3%. A 2014 report described a participatory and inclusive MSNP development process, enabled by high-level champions. Recommendations to address identified challenges included urgent improvement in nutrition capacity at district and sub-district levels and continued targeted advocacy; actions have been taken. Moving ahead, there is a need to map interventions and their coverage, stakeholders and resources at district level, identifying gaps; and to develop budget codes for nutrition to facilitate tracking on spend. The six-step process of development for MSNP II (2018-2022) is underway, led by the National Planning Commission, Government of Nepal together with UNICEF.

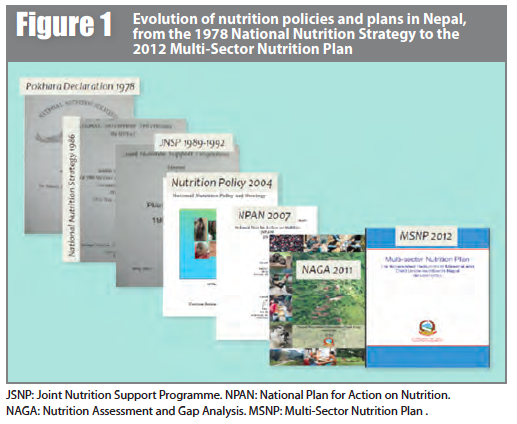

Multi-sector thinking on nutrition programming in Nepal began back in 1978 with the first National Nutrition Strategy, followed in 1986 by the Second Nutrition Strategy. These were jointly known as Pokhara Declaration I and II (see Figure 1). Subsequently, the Joint Nutrition Support Programme (JNSP) (1989-1992) was the first attempt at multi-sector programming for nutrition. However, due to poor engagement of sectors while formulating the programme and hence poor ownership, the JNSP had limited success. The 2004 National Nutrition Policy proved to be the first effective response. Developed by the health sector, it was immediately implemented through its annual work plan and budget, with key indicators included in the Health Management Information System (HMIS) and monitored.

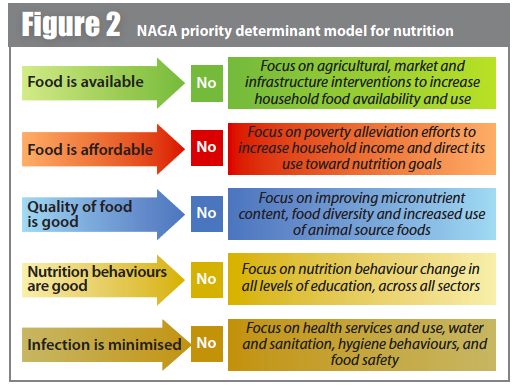

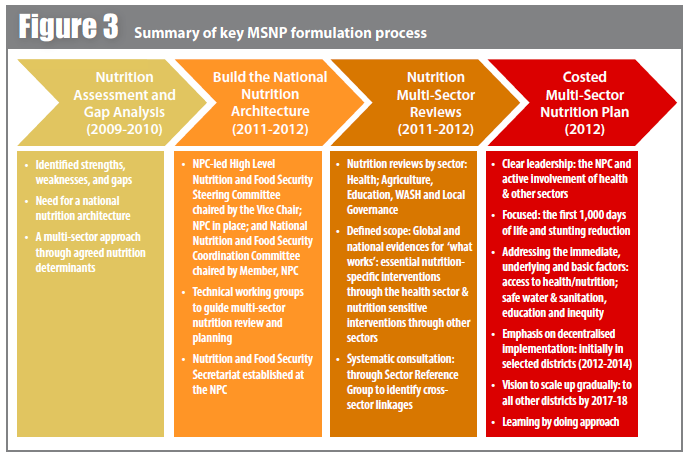

In 2009, the Nutrition Assessment and Gap Analysis (NAGA) identified strengths, weaknesses and gaps in nutrition programing. Primary determinants of undernutrition identified in the NAGA included inadequate food availability, access and affordability; poor food and care-related behaviours; inadequate food quality/nutrient density; and high prevalence of infection, which reduces food absorption and utilisation (see Figure 2). These reflected the need for a multi-sector approach. Recommendations from NAGA were endorsed by the National Planning Commission (NPC) in 2011 and a Memorandum of Understanding was formally signed between NPC and UNICEF to develop a Multi-Sector Nutrition Plan (MSNP) in Nepal (see Figure 3).

MSNP development and rollout

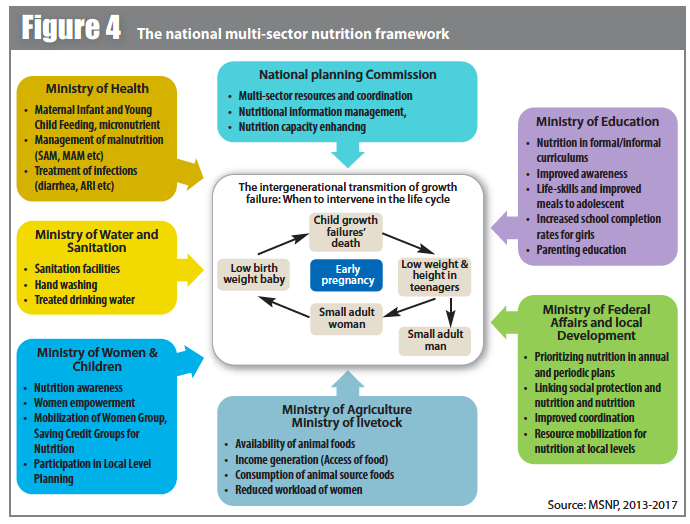

In May 2011, Nepal joined the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement, the fifth country to join and an ‘early riser’. This reflected and reinforced the political space and momentum for nutrition in Nepal. In the same year, two national committees on Nutrition and on Food Security were merged into one, the High Level Nutrition and Food Security Steering Committee, chaired by the Vice-Chair of the NPC with secretaries of the relevant ministries as members. Various reference groups were formed consisting of government officials, development partners, academia and independent sector experts, to guide multi-sector nutrition reviews and planning in both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive sectors (health, education, governance, WASH and Agriculture). Their defined scope was to review global and national evidences for ‘what works’.

Through systematic consultations within and between reference groups, each sector formulated its nutrition objectives and strategies and developed log frames with clear outcomes, outputs and activities. These were later costed and consolidated into one national document - the MSNP - with clear goals and indicators, five-year plans (2013-2017) and ten-year visions (to 2022).

The MSNP was approved by the cabinet of ministers in August 2012 and launched by Prime Minister Dr Baburam Bhattarai in September 2012. Declaration of Commitment for implementation was signed by the NPC, secretaries of the sector ministries, representatives of the United Nations (UN) and development partners, civil society and the private sector.

A high-level coordination committee, chaired by the honourable member of the NPC, was formed at central level to strengthen coordination across government ministries and development partners. In addition, a National Nutrition and Food Security Secretariat was established in 2013 to support the high-level steering and the coordination committee, particularly in strengthening the capacity of sectors in nutrition planning, advocacy, communication, monitoring and evaluation.

Decentralised (district) implementation

The MSNP offered a platform to integrate ‘top-down’ nutrition plans from the central sector ministries on delivering essential nutrition services, as well as ‘bottom-up’ nutrition plans made at community and district level that contextualise and prioritise the central plans for implementation. Implementation was planned initially in six districts (Achham, Bajura, Jumla, Kapilvastu, Nawalparashi and Parsa) with a view to gradually scaling up through a ‘learning-by-doing’ approach. This was necessary as there was no global guidance on multi-sector, decentralised implementation. Learning was gathered in each district through district-level reviews and at steering committee meetings. A few studies were also undertaken and experiences documented in a review of the MSNP development process in 2014 (see below).

Nutrition and Food Security steering committees were formed initially in all six districts and in village development committees (VDCs); these bodies are proposed in all VDCs, municipalities and districts, in addition to national level. Nutrition ‘focal officers’ were identified in the districts and trained on MSNP planning and implementation. This model has now been scaled up to cover more than 50 (out of 75) districts as of 2016.

The Multi-sector Nutrition and Food Security Communication and Advocacy Strategy was put in place in 2015 and a national Golden 1,000 Days public awareness campaign was launched in April 2016 to further operationalise the strategy.

Nutrition resourcing and programming

Nutrition budget allocations were determined by analysis by budget heads of different ministries. Cost categories for nutrition-sensitive interventions varied from an estimated 5% to 75% contribution to nutrition. For example, for agriculture, the weighting varied from 10% (e.g. agricultural extension) to 50% for an agriculture and food security project. The cost contribution of nutrition-specific programmes was 100%.

After establishing the MSNP, resources and level of programming on nutrition, particularly on nutrition-sensitive, have significantly increased in Nepal, both through government and development partners. Figure 5 reflects the upward trend in expenditure from 2013-14 to 2015-16. Government funds make up around 40% of all nutrition allocations and closer to 50% of expenditures. Significant projects currently being implemented in line with MSNP include Suaahara II; Feed the Future (USAID funded); Agriculture and Food Security Project (AFSP) and Golden Thousand Days (World Bank funded); and the EU-UNICEF partnership for scaling up MSNP.

Impact and lessons to date

Although formal evaluation of MSNP has yet to be undertaken, the National Multi-Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2014 revealed that the prevalence of stunting has fallen to 37%, with improvements in infant and young child feeding practices. The average annual rate of reduction of stunting from 2001 (DHS) to 2014 (MICS) is 3.3% (DHS 2001 - 57%; DHS 2006 - 49%, DHS 2011 - 41%). The upcoming national DHS 2017 will shine further light on the impact of the implementation of MSNP on nutrition.

A process of documenting the MSNP was undertaken in 2014 (Shrimpton et al, 2014), which highlighted that the MSNP development process was participatory and inclusive. Furthermore, there is an enabling environment for multi-sector collaboration in Nepal with high-level champions of nutrition. Coordination has improved between stakeholders both at district and national levels. However, the study also highlighted that there is a limited national nutrition capacity, lack of common understanding among all stakeholders and between sectors at central and district level; and need for intensive efforts at district level to ensure effective implementation.

Recommendations included urgent improvement in nutrition capacity at district and sub-district levels and continued advocacy to ensure a consensus-driven results framework for district level decision-making for the MSNP. Acting on these, the 2015 Communication and Advocacy Strategy was one major effort to develop common understanding. The MSNP training manual at central, district and VDC levels was also updated to facilitate this. Regarding capacity development, the MSNP planning Training of Trainers (ToT) has been completed so far for focal officers from different sectors at 17 districts and is planned for the remaining 11 districts by April 2017. The Maternal Infant and Young Child Nutrition Training (as part of health-sector nutrition) was undertaken in more than 50 districts of Nepal through UNICEF, Ministry of Health and partners like Suaahara/USAID.

Challenges in implementing the MSNP remain. There is still work to be done to achieve common understanding, commitment and ownership of MSNP by all ministries and stakeholders; a need to mainstream resources and minimise duplication; and rollout of the full MSNP intervention package is needed in all districts. There is limited budget absorptive capacity of the line ministries and a need for continued and strengthened coordination at national and local levels. Furthermore, there is limited institutional and human-resource capacity within sectors at all levels. An effective implementation-monitoring framework for the MSNP is still required.

![]()

Next steps

Moving forward, there is a need to map interventions and their coverage, stakeholders and resources at district level and identify gaps.

Periodic financial tracking of investment and expenditure is necessary. The National Planning Commission has now determined that a budget code for nutrition is needed to effectively track investment and expenditure. Nutrition-sensitive costing (proportional allocations to nutrition) to date has required manual analysis by the budget head of different ministries. Budget codes would allow the Ministry of Finance to undertake nutrition-sensitive budgeting at the budget source every year.

The multi-sector architecture at all levels (national, regional, district, municipality and VDCs) needs to be further strengthened and made more functional. For example, committees need to meet more frequently at strategic times, particularly during district-level planning and budgeting, as well as ensure quality of implementation.

The NPC, Government of Nepal has requested UNICEF to lead the process of drafting the new phase of MSNP (MSNP II). This will update and build upon MSNP I, rather than develop a completely new plan. The roadmap for MSNP II (2018-2022) formulation has six steps, already underway:

- Deprivation Analysis (By Aug 2016) - Led by UNICEF, this was undertaken to understand the current levels and trends of deprivation, including indicators of malnutrition, their severity and where are they prevalent.

- Causality Analysis (Sept 2016) -- Causality of malnutrition (including under and over-nutrition) was analysed by context, focusing on three typologies where the prevalence of undernutrition is high and problems are distinct: the Terai; the Mid and the Far-West mountains and hills; and the rest of the country.

- Review of MSNP I Implementation (March 2017) - A systematic review of MSNP implementation to identify achievements, gaps, lessons learned and best practices will be undertaken by independent expert(s) in consultations with relevant stakeholders. The report is due mid-2017.

- Finalising the Theory of Change (March/April 2017) - Planned.

- Finalising the write-up of MSNP II (by mid-2017) - Planned.

- Endorsement/Approval by Government) - Planned.

Thus development of MSNP II (2018-2022) will be informed by reviews, situation analyses, causality analyses, theory-of-change programming and the latest global and national evidence on nutrition.

For more information, contact: Pradiumna Dahal, Nutrition Specialist, UNICEF Nepal, email: pdahal@unicef.org

References

Shrimpton et al, 2014. Shrimpton RJ, Crum S, Basnet S, Mebrahtu S and Dahal P. 2014. Documenting the process of developing the Nepal Multi-sector Nutrition Plan and identifying its strengths and weaknesses: Report of a research project. Kathmandu, Nepal: UNICEF/European Union.