Recommendations for multi-sector nutrition planning: Cross-context lessons from Nepal and Uganda

By Amanda Pomeroy-Stevens, Heather Viland and Sascha Lamstein

Amanda Pomeroy-Stevens is a Research and Evaluation Advisor on the USAID SPRING Project (JSI). While with SPRING she was principal investigator of the Pathways to Better Nutrition studies and has led work on nutrition financing and nutrition-related, non-communicable disease prevention.

Amanda Pomeroy-Stevens is a Research and Evaluation Advisor on the USAID SPRING Project (JSI). While with SPRING she was principal investigator of the Pathways to Better Nutrition studies and has led work on nutrition financing and nutrition-related, non-communicable disease prevention.

Heather Viland is a project coordinator for the SPRING project at JSI. Prior to joining SPRING she worked as an educator internationally and in Washington, DC.

Dr Sascha Lamstein leads SPRING’s work on promoting systems thinking and strengthening for nutrition. Dr Lamstein has over 20 years’ experience in health and nutrition projects.

This article summarises work completed by the USAID SPRING Project Pathways to Better Nutrition Research Teams in Uganda and Nepal (Amanda Pomeroy-Stevens, Nancy Adero, Alexis D’Agostino, Hannah Foehringer Merchant, Abel Muzoora, Daniel Lukwago, Diana Tibesigwa, Herbert Mona, Edgar Agaba, Lidan Du, Ezekiel Mupere, Madhukar B Shrestha, Monica Biradavolu, Kusum Hachhethu, Robin Houston, Indu Sharma, Jolene Wun and Manisha Shrestha). The authors would like to acknowledge Gwyneth Cotes for her support in drafting and reviewing this article. This study was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of JSI and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Location: Nepal and Uganda

What we know: A multi-sector approach to addressing undernutrition is increasingly reflected in national multi-sector nutrition action plans (NNAPs).

What this article adds: SPRING Pathways to Better Nutrition (PBN) case studies documented successes and challenges in implementing NNAPs in Nepal and Uganda at national and sub-national level. A longitudinal, mixed-methods approach was applied across multiple levels of governance, gathering qualitative and budgetary data over two years. Common drivers of change across both countries included strong multi-sector coordination of nutrition activities that involved national nutrition secretariats and strong advocacy partnerships and communication. Barriers to change included vertical coordination, poor coordination with academia and business, high staff turnover and constrained staff availability. Integrating NNAPs into existing local and national policy and work planning structures, budgeting processes and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) systems remains a key challenge. Linked to NNAPs, increased prioritisation of nutrition across sectors and increased funding allocation for nutrition was observed; however, nutrition spend did not necessarily increase. Lack of clear accounting mechanisms for nutrition-related allocations and spending limited analysis. Cross-country recommendations include: setting long-term goals for scale-up; all partners, including donors and UN agencies aligning with NNAPs; consideration of formal funding mechanisms for nutrition; and embedding nutrition into national strategies, financial reporting systems and M&E mechanisms.

Background

A multi-sector approach is often thought to be the most effective way to address undernutrition (Levinson, Balarajan and Marini, 2013). Many countries have instituted national multi-sector nutrition action plans (NNAPs), an important first step in advocating for multi-sector nutrition action. However, an NNAP alone will not achieve nutrition goals at scale: these plans must be translated into improved commitment, financing and programmes from national down to community level. SPRING’s Pathways to Better Nutrition (PBNN) case studies spent two years analysing the changes in Nepal and Uganda following the rollout of their NNPs. The results of the studies, released in 2016 and documented in the Food and Nutrition Bulletin (see references), provide insight into how nutrition policy influences stakeholders’ understanding, prioritisation and funding for nutrition-related activities.

The Strengthening Partnerships, Results and Innovation in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) project recently completed these PBN case studies in Nepal and Uganda (Pomeroy-Stevens, Biradavolu et al, 2016; Pomeroy-Stevens, D’Agostino et al, 2016). When SPRING began these studies, both countries had adopted multi-sector plans (Nepal in 2013 and Uganda in 2011) and had appointed coordinating bodies within high-level offices (the National Planning Commission (NPC) in Nepal and the Office of the Prime Minster (OPM) in Uganda. (Government of Nepal and National Planning Commission, 2012; Government of Uganda, 2011). The roles of these coordinating bodies vary by country, but generally they are responsible for convening and coordinating NNAP stakeholders across multiple sectors and organisations. Both countries engaged key sector ministries, donors, United Nations groups, academia and civil society organisations (CSOs) in developing the plans. Both countries had also joined the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement in 2011 and had signed onto other relevant global nutrition agreements, which helped to inform the goals and targets included in the final NNAPs. In the case of Nepal, SUN (via REACH) helped to staff the secretariat.

The PBN case studies sought to document how nutrition is prioritised under these NNAPs and how that prioritisation, in turn, influences the funding of nutrition, knowing that these are important intermediate steps in improving nutrition outcomes. We identified successes and challenges that provide lessons for other countries seeking to develop and implement similar NNAPs.

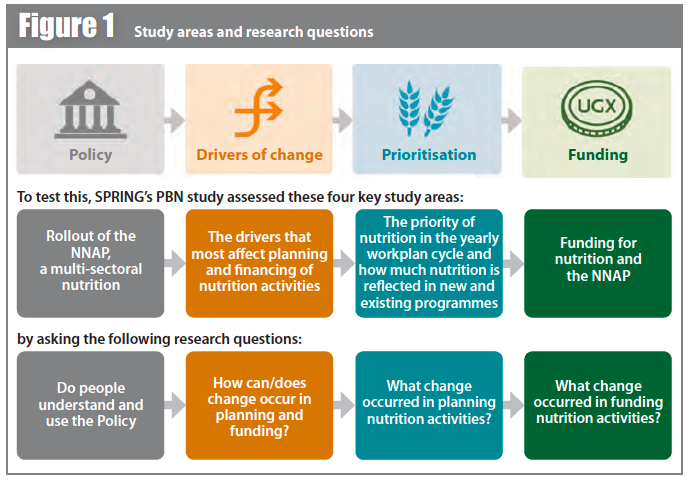

As shown in Figure 1, SPRING hypothesised that the NNAPs in Uganda and Nepal would positively influence stakeholders’ understanding of the policy, leading to changes in planning and action for nutrition and greater prioritisation, resulting in increased funding for nutrition over the two years of the study.

Methods

Nepal and Uganda were selected to represent countries with similar nutrition goals but different contexts. They were also chosen because they have been successful, relative to other countries, in reducing undernutrition, developing NNAPs and achieving World Health Organization (WHO) nutrition governance targets (WHO 2014). Two to three districts were selected in a similar fashion in each country. In Nepal, one village development committee (VDC) per district was also selected. The district and VDC selection were not meant to be representative; rather they are examples of districts and VDCs that have already begun the NNAP rollout process and are actively addressing malnutrition.

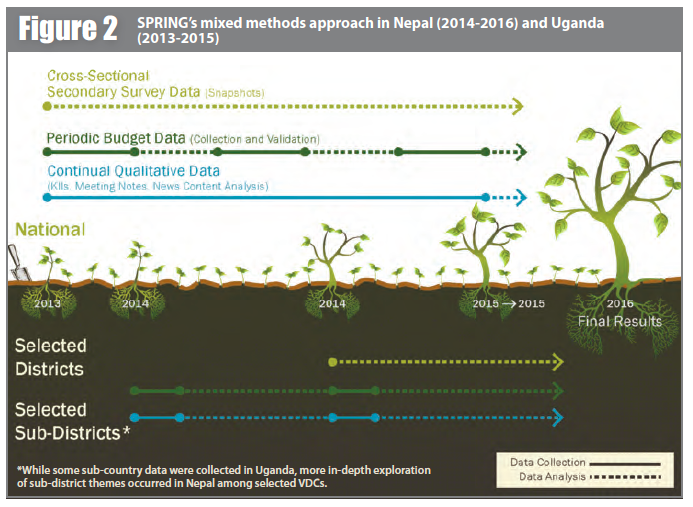

To answer the research questions (Figure 1), a longitudinal, mixed-methods approach was applied across multiple levels of governance (see Figure 2). Methods are fully described elsewhere (Pomeroy-Stevens, Shrestha et al, 2016; Pomeroy-Stevens, Adero et al, 2016); in brief, SPRING collected both qualitative and budgetary data. Qualitative data were collected primarily through repeated, in-depth, key informant interviews (KIIs), review of minutes from meetings related to the NNAP and weekly analysis of content from major national newspaper outlets. A broad selection of stakeholders was selected for regular interviews, representing the government, donors, UN groups, the private sector, academia, and civil society.

Publicly available budget data were analysed and validated annually. SPRING’s approach to nutrition budget analysis (which included analysis of both the allocated budget and the actual expenditures), which was developed for these studies, has now been documented in a user’s guide and tool, available on the SPRING website (www.spring-nutrition.org/publications/series/users-guide-nutrition-budget-analysis-tool).

*While some sub-country data were collected in Uganda, more in-depth exploration of sub-district themes occurred in Nepal among selected VDCs.

Findings

While many useful context-specific insights came out of both country studies, some lessons appeared to span both countries.

Drivers of change in nutrition policy and programming

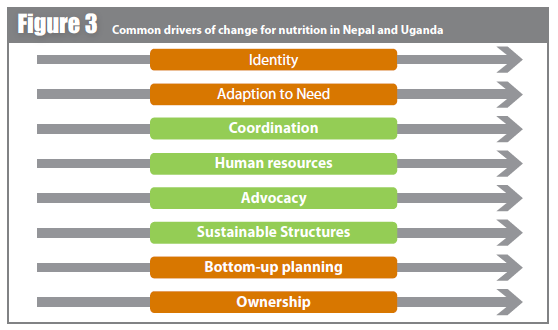

SPRING identified a number of factors that facilitated or hindered the influence of the NNAPs. We call these “drivers of change.” Although there were differences between the two countries, some drivers appeared to be universal across both contexts (Figure 3). In this figure, the drivers of change that cut across both countries are shown in green; those in orange were found only in one country.

Common drivers of change across countries

Multi-sector coordination of nutrition activities: Coordination of nutrition planning, funding and implementation across sectors, stakeholders and government levels was identified by nearly all stakeholders as critical for scaling up nutrition programming. Changes in decision-makers’ behaviours and perceptions, as a result of improved coordination, can make a large difference when it comes to what is prioritised and funded.

Across both countries, stakeholders reported that multi-sector coordination at national level improved during the study period; many attributed this improvement to the NNAP structures. Moreover, there has been greater acceptance of the nutrition secretariats (the NPC in Nepal and the OPM in Uganda) as coordinating bodies. It was also noted that, over the course of the study, working groups or technical committees became more active, with regular coordination meetings and greater participation of different sectors during meetings.

Stakeholders also reported improvement in inter-sector coordination; increased understanding of multi-sector approaches to nutrition and the importance of such an approach to combatting malnutrition; increased understanding of the purpose and content of their NNAP; and increased understanding of each sector’s roles and responsibilities in supporting the NNAP.

Some constraints were also noted in coordination across both countries. Vertical coordination (coordination between national, district and community levels) was identified as a key barrier to implementation of nutrition activities. In both Nepal and Uganda, structures had been established for coordination at the district level and below, but many stakeholders felt that these structures remained isolated from the national level, due to a breakdown in feedback loops, inadequate time given for lower-level work planning and lack of budget flexibility at the local level.

Coordination with the private sector and academia was also a struggle. While we did see an increase in private sector organisations’ interest in nutrition and the NNAPs in both countries, this had not yet translated into increased engagement. Key informants from private sector organisations in Nepal felt they needed a nutrition focal person dedicated to coordinating private sector actions and meeting with private sector representatives. Key informants from academia were frustrated with the stalled progress and concerned with the lack of engagement of academia. During the study period, the academic and private sector coordination working groups either did not exist, or their creation had stalled and no meetings were convened.

Human resources: An important driver of change in how nutrition is prioritised and funded is the level of human resources that are committed and made available for nutrition. Human resources include all people engaged in nutrition, including clinical and community providers, policy makers, programme managers and support staff at every level in every stakeholder group.

High staff turnover was one of the biggest human-resource constraints in both countries, across all levels, stakeholder groups and sectors. This was also true of the NNAP focal positions, with just under half of these positions turning over in both countries and an additional position in Uganda and two positions in Nepal going vacant during the period of the study. This affected institutional memory and commitment to nutrition and contributed to delays in spending funds earmarked for nutrition.

Staff availability was another universal human-resources issue. This particularly affected government staff and provider and policy-making positions in hard-to-reach areas. This shortage of staff meant that often one person had to hold several positions, leading to burnout and reducing staff interaction on key NNAP committee meetings.

Advocacy for nutrition: Advocacy for nutrition is a critical driver in convincing governments and development partners to prioritise and allocate funds for nutrition. Advocacy was an area in both countries where we saw regular multi-sector activities and regular partnerships between the government, funders (donors and UN groups) and CSOs. Both countries saw major advocacy milestones during the study period, including the launch of advocacy and communication working groups and strategies, and successful lobbying for new nutrition activities. Beyond that, the successes and formation of efforts varied quite a bit.

Another universal aspect was the desire and need for advocacy to happen at many levels, from grassroots to the highest echelon. In both countries there was persistent concern about how to fully engage parliamentarians and other high-level champions in the nutrition effort.

Sustainable structures: To maintain momentum for nutrition or accelerate progress, structures and processes for planning, funding, implementing and monitoring nutrition activities must be in place. Stakeholders have an important role in ensuring that nutrition is embedded in existing local and national policy and work-planning structures, budgeting processes and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) systems in order to ensure sustained commitment to nutrition.

We heard a lot about the importance of building nutrition into existing systems in both countries, especially financing and M&E structures (planning structures were also discussed but often in more indirect terms). Both countries were considering options for creating more permanent financing mechanisms (including tracking codes, budget lines and pooled funds), but only Nepal had instituted a budget line designated for nutrition by the end of the study.

Building nutrition indicators into M&E strategies and structures seemed a particularly difficult issue in both countries. Despite what appeared to be significant effort and discussion both before and during the study period, the NNAP M&E frameworks in both countries had still not become operationalised as of 2016. Some of the difficulties that crossed over in both contexts included sensitivity on who has to report M&E data to whom across sectors and stakeholder groups and how to develop or strengthen reporting up from the districts and below.

Successes in understanding and increased priority of nutrition across sectors

Understanding is pivotal to creating high-level coordination and implementation at scale. We found that, over the course of the study, understanding and use of the NNAP by all nutrition stakeholders increased. This included not just understanding the purpose and content of the NNAPs, but also understanding each stakeholder group’s roles and responsibilities for supporting the policy. We also found that NNAPs expanded or increased knowledge of nutrition as a multi-sector issue, addressed by nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive actions, at least down to district level. This appeared to be facilitated in both countries by local and regional trainings coordinated by nutrition secretariats.

Regarding the extent to which nutrition was seen as a priority, it appeared that one of the main mechanisms to indicate this (and translate it into action) was to name nutrition as a priority in sector or organisational strategy documents.

In Nepal, three of six sectors had nutrition as a named priority by the end of the study and the education sector had elevated it to core theme (which doesn’t designate funding but increased the visibility of nutrition within the ministry). These changes came about after months of internal discussions, advocacy for nutrition and changes to internal organisational structures (including creation or promotion of nutrition units and creation of nutrition staff positions).

In Uganda, there was increased activity to move toward including nutrition as a named priority in strategy documents by three ministries (Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF); Health (MoH); and Trade, Industry and Cooperatives (MTIC)), although this had not resulted in formal inclusion as of 2015.

Few major changes were noted in the way nutrition was included in strategy documents for donors and UN groups, but this is in part due to the five-year life of many UN policies and strategies. Ministries often noted the NNAP’s influence on their sector strategy, whereas donors and UN groups were more likely to cite the global nutrition agenda for any changes to their strategy documents.

Challenges in tracking and spending nutrition funding

SPRING posited that increased prioritisation of nutrition should, in theory, increase allocations and spending on nutrition activities. In general across both countries, we did see that where there were clear increases in priority (through inclusion of nutrition in strategy documents and advocacy and approval for new nutrition activities), increased funding was also allocated for nutrition.

This was particularly true for Nepal, where increased planning and priority for nutrition resulted in steady increases in nutrition-related allocations of about 17 per cent per year, with a quarter of this funding dedicated to new NNAP-related activities.

In Uganda, where nutrition is not identified as a named priority in sector plans, no new activities were planned, resulting in no new nutrition-related funding over time. Nutrition-specific allocations made up between 11 and 32 per cent of these totals, depending on the country and whether allocations were run within the government budget or not. In both countries, even when allocations increased within a sector or organisation, it did not always result in more available funding, because actual spending on nutrition did not always increase. However, measurement of this gap was complicated due to missing expenditure data.

Across both countries, there was a lack of clear accounting mechanisms for nutrition-related allocations and spending, especially for funding from external development partners (EDPs) that is managed outside the official government budget. Tracking this “off-budget” funding is a challenge faced by many countries, not just Nepal and Uganda (D’Agostino et al, 2016). Both Nepal and Uganda launched Aid Management Portals during the course of this study to help deal with this limitation and Nepal updated its development cooperation policy to try to ensure better reporting. Within government, a few ministries have created nutrition and/or food security units, divisions or departments, which help to clarify where to find nutrition-related funds.

SPRING was able to analyse on-budget spending data and we compared these findings to qualitative data on stakeholder’s perceptions of why allocations were not fully spent. While some context-specific factors came into play, the two primary reasons given in both countries for money not being fully spent were delayed release of funds to projects (due to delays in ministries authorising the budget releases) and procurement delays at the local level (due to the lengthy bidding and proposal process required for any activity involving purchase of capital investments or commodities). These factors led to delays of multiple months in both countries, effectively reducing the length of the financial year and the time to spend allocations.

Cross-context recommendations

Country-specific recommendations can be found elsewhere (Pomeroy-Stevens, Shrestha et al, 2016; Pomeroy-Stevens, Adero et al, 2016). Here, we have compiled recommendations that applied across both study contexts. While this does not mean they are applicable to every country with an NNAP in place, the recommendations may provide useful insights to countries at similar stages of the policy-making process.

Take a long view of scale-up.

Nepal has a long history of incorporating nutrition into its plans, so it may be easier for countries with an existing nutrition focus to develop a plan and incorporate spending. The UNAP in Uganda, on the other hand, is the first truly multi-sector NNAP; therefore more time may be needed to achieve the goal of reducing undernutrition. Several stakeholders mentioned how important it is to sustain commitment to scaling up nutrition and noted that it may take until the end of the second or even the third iteration of UNAP before large-scale changes in undernutrition status are evident (Pomeroy-Stevens et al, 2014). These observations suggest that nationwide scale-up of nutrition programmes will take longer than the full tenure of the next five-year nutrition plan. Governments implementing similar NNAP should set longer-term goals and targets (e.g. over 15 to 20 years) for how and when to scale up nutrition programmes fully.

Reach the lowest level.

Local-level policy and decision makers are key assets to help increase understanding and the importance of nutrition across multiple sectors, especially in urban development and education. Their increased awareness will help generate demand for nutrition in the local planning process. Both Nepal and Uganda faced obstacles to achieving improved understanding and prioritisation of the NNAP at the lowest level (i.e. the sub-district and community level) due to staff availability, lack of NNAP operational guidelines and lack of NNAP M&E guidance for nutrition (Adero et al, 2016; Biradavolu et al, 2016). Other countries need to plan how to reach this level as they design their NNAP and NNAP operational guidelines.

Build sustainable structures.

While both Nepal and Uganda have embedded NNAP coordinating bodies within the government, much of the planning, financing and monitoring of NNAP activities is done ad hoc on a year-to-year basis and often outside government structures like sector planning documents, the budget and information systems. Although it is sometimes easier and quicker to build systems for planning, financing and monitoring NNAPs outside these existing structures, it is vital to build long-term, systemic commitment for nutrition within them. Consider how to embed nutrition into planning strategy documents, financial reporting systems and M&E mechanisms.

Address constraints on human resources for nutrition.

Insufficient human resource is not unique to nutrition; many major international initiatives are dedicated to finding solutions for this issue. What is unique to nutrition is a lack of dedicated training pipelines, professional support services and standardisation of core curriculum. Government funding will be necessary to address some of these issues, but EDP support is also needed. Innovative solutions are needed to prevent staff who are already in nutrition positions from leaving. This could be done through incentive programmes, procedures for hand-off of existing positions and targeted training to ensure staff feel prepared to do their job. Any increase in dedicated nutrition funding could also provide a more consistent resource envelope for nutrition-related positions in both government and non-government organisations.

Launch monitoring and evaluation frameworks.

In both countries, M&E frameworks were not launched until the end of the plan. The complexity of these frameworks will encourage lengthy deliberation, but countries who want to learn from the experience of Nepal and Uganda may want to launch a draft M&E framework earlier, even in the first year of the NNAP, and then allow for iterative editing to make sure that at least those indicators most crucial to decision-making and evaluation are being collected from the start of the NNAP. The ability to show what has been accomplished by the NNAP (either through simple counts of those served or more long-term nutrition outcomes) is one of the most important ways to keep stakeholders motivated.

Align with NNAP.

All partners working in nutrition should align planned activities with the NNAPs. Evidence indicated that while EDPs in Nepal and Uganda (particularly donors and UN groups) gave substantial support to nutrition activities, they seemed primarily to follow their own global agenda for nutrition. EDPs working in other countries with NNAPs should increase their efforts to align and support those plans.

Embed nutrition in sector and organisational plans.

One way to help partners remember to incorporate the prioritisation of the NNAP is to use it as a guiding document to reframe sector and organisational plans to get everyone on the same page. In addition, the more policies and plans that list nutrition as a priority, the more likely that greater funding for new activities will be allotted. Commitment to nutrition can be accelerated and sustained if it is included as a top priority in each sector’s investment and development plans and within each district’s development plans. The specifics of this recommendation may need to be adjusted to each country’s planning structures and documents, but the essence remains that nutrition needs to be embedded in each sector.

Use budgets as planning tools.

We found that some ministries and CSOs were not using budgets as an integral part of their nutrition-activity planning process. Increasing the usage and budget literacy of nutrition technical people would increase demand for accurate and timely spending data.

Invest in key drivers of change.

When governments put money towards something, it attracts other sources of funding because it demonstrates a government’s commitment to that idea. Countries looking to operationalise their NNAPs should explore how to seed-fund key drivers of change. This could be done by providing funds or other non-monetary commitments to establish and maintain coordination mechanisms, human resources and advocacy activities, and embed nutrition into existing structures.

Consider formal funding mechanisms for nutrition.

While it is not necessary for governments to establish formal funding mechanisms like a budget line or a tracking code for nutrition, it is important for countries with NNAPs to explicitly state how the NNAP will be financed and how to monitor allocations and spending throughout the policy cycle. Some form of routine nutrition budget tracking must be put into place to increase transparency and accountability for nutrition spending. Peru and Guatemala are good examples of routine nutrition-budget tracking within government reporting systems (Victoria et al, 2016).

Conclusions

Even the most comprehensive multi-sector NNAP must influence key drivers of change before it can create improvements in prioritising and funding nutrition activities. The findings from the PBN studies indicate that the governments of Nepal and Uganda and their partners have made positive progress toward multi-sector coordination of nutrition work and that NNAPs have been influential in fostering such coordination, as well as other country-specific changes in advocacy and sustainable structures for nutrition. In the case of Nepal, this led to new nutrition activities and greater nutrition-related funding. While these studies only covered two country contexts, we believe that some useful lessons can be learned from their experiences and recommendations provided from the PBN case studies can help in many other countries that are planning and implementing multi-sectorly.

For more information, contact: Amanda Pomeroy-Stevens, email: heather_viland@jsi.com

References

Adero et al 2016. Nancy Adero, Edgar Agaba, Abel Muzoora, Daniel Lukwago, Hannah Foehringer Merchant, Alexis D’Agostino, Ezekiel Mupere and Amanda Pomeroy-Stevens. 2016. District Technical Brief: Summary of Qualitative Findings in Kisoro and Lira Districts, Uganda 2014 and 2015. Pathways to Better Nutrition Case Study Evidence Series. Arlington, VA: SPRING Project.

Biradavolu et al, 2016. Monica Biradavolu, Amanda Pomeroy-Stevens, Madhukar B Shrestha, Indu Sharma, and Manisha Shrestha. 2016. Adapting National Nutrition Action Plans to the Subnational Context: The Case of Nepal. Technical Brief #3. Pathways to Better Nutrition Case Study Evidence Series. Arlington, VA: Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project.

D’Agostino et al, 2016. Alexis D’Agostino, Amanda Pomeroy-Stevens, Clara Picanyol, Mary D’Alimonte, Patrizia Fracassi, Hilary Rogers and Shan Soe-Lin. 2016. Panel 7.3 Global Partners Harmonize Technical Support On Budget Analysis. In Global Nutrition Report 2016: From Promise to Impact: Ending Malnutrition by 2030, 85. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Government of Nepal and National Planning Commission, 2012. Multi-Sector Nutrition Plan For Accelerating the Reduction of Maternal and Child Under-Nutrition in Nepal: 2013-2017. Kathmandu, Nepal: GoN, NPC. scalingupnutrition.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Nepal_MSNP_2013-2017.pdf.

Government of Uganda, 2011. Uganda Nutrition Action Plan 2011-2016: Scaling Up Multi-sector Efforts to Establish a Strong Nutrition Foundation for Uganda’s Development. Kampala, Uganda: Government of Uganda.

Levinson, Balarajan and Marini, 2013. James F Levinson, Yarlini Balarajan and Alessandra Marini, 2013. Addressing Malnutrition Multisectorally: What have we learned from recent international experience? New York, NY: UNICEF, MDGF. www.aecid.es/Centro-Documentacion/Documentos/Divulgación/Addressing_malnutrition_multisectorally_MDG_F_Item1_Final-links.pdf.

Pomeroy-Stevens et al, 2014. Amanda Pomeroy-Stevens, Alexis D’Agostino, Lidan Du, Nancy Adero, L Sserunjogi, E Mupere and A Muzoora. 2014. Understanding Scale-up in the Context of the Ugandan Nutrition Action Plan. Technical Brief #1. Pathways to Better Nutrition Case Study Evidence Series. Arlington, VA: Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project.

Pomeroy-Stevens, Adero et al, 2016. Amanda Pomeroy-Stevens, Nancy Adero, Alexis D’Agostino, Hannah Foehringer Merchant, Abel Muzoora, Daniel Lukwago, Diana Tibesigwa, Edgar Agaba, Lidan Du, and Ezekiel Mupere. 2016. Pathways to Better Nutrition in Uganda: Final Report. Pathways to Better Nutrition Case Study Evidence Series. Arlington, VA: Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project. www.spring-nutrition.org/publications/reports/pathways-better-nutrition-uganda-case-study.

Pomeroy-Stevens, Biradavolu, Shrestha et al, 2016. Amanda Pomeroy-Stevens, Monica Biradavolu, Madhukar B Shrestha, Kusum Hachhethu and Robin Houston. 2016. Prioritizing and Funding Multisectoral Nutrition in Nepal. Food & Nutrition Bulletin 37 (suppl 4): 151–69. doi:10.1177/0379572116674555.

Pomeroy-Stevens, D’Agostino et al, 2016. Amanda Pomeroy-Stevens, Alexis D’Agostino, Nancy Adero, Hannah Foehringer Merchant, Abel Muzoora and Ezekiel Mupere. 2016. Prioritizing and Funding Multisectoral Nutrition in Uganda. Food & Nutrition Bulletin 37 (suppl 4): 124–41. doi:10.1177/0379572116674554.

Pomeroy-Stevens, Shrestha et al, 2016. Amanda Pomeroy-Stevens, Madhukar B Shrestha, Monica Biradavolu, Kusum Hachhethu, Robin Houston, Indu Sharma and Jolene Wun. 2016. Pathways to Better Nutrition in Nepal: Final Report. Pathways to Better Nutrition Case Study Evidence Series. Arlington, VA: Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project. www.spring-nutrition.org/publications/reports/pathways-better-nutrition-nepal-case-study.

Victoria et al, 2016. Paula Victoria, Ariela Luna, Jose Velasquez, Rommy Rios, German Gonzalez, William Knechtel, Vagn Mikkelsen and Patrizia Fracassi. 2016. Panel 7.1: Guatemala and Peru: Timely Access to Financial Data Makes a Difference in Actual Spending and Spurs Accountability at All Levels. In Global Nutrition Report 2016: From Promise to Impact: Ending Malnutrition by 2030, 83. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/130354/filename/130565.pdf.

WHO, 2014. Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLIS). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. apps.who.int/nutrition/landscape/report.aspx?iso=UGA.