Scaling up CMAM in protracted emergencies and low resource settings: experiences from Sudan

By Tewoldeberhan Daniel, Tarig Mekkawi, Hanaa Garelnabi, Salwa Sorkti and Mueni Mutunga

Dr Tewolde is a Nutrition Specialist with UNICEF Kenya Country office. He has worked in Kenya, Ethiopia and Sudan in the areas of health system strengthening for Community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM), emergency nutrition, micronutrients, public health and child survival.

Dr Tarig Mekkawi is a Nutrition Specialist with UNICEF Sudan country office. He has 12 years’ experience in CMAM and nutrition programming in emergency and development contexts.

Hanaa Garelnabi is CMAM National Coordinator for the Federal Ministry of Health in Sudan. Hanaa has seven years’ experience in experience in programme monitoring and management.

Salwa Sorkti is the Director of National Nutrition Program within the General Directorate of Primary Health Care, Federal Ministry of Health, Sudan. Previously she served as the Director of the Nutrition Department, Ministry of Health, Red Sea State Sudan.

Mueni Mutunga is the Chief of Nutrition in the UNICEF Sudan Country office and has previously worked in Sierra Leone, Chad, South Sudan, and Kenya in nutrition programming in emergency and development contexts.

The authors would like to thank Janneke Blomberg for reviewing and providing constructive inputs to this paper.

The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this article are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of UNICEF, its Executive Directors, or the countries that they represent and should not be attributed to them.

Click here for an interview (Arabic) with the authors on ENN's Media Hub

Click here for an interview (English) with the authors on ENN's Media Hub

Location: Sudan

What we know: Recent years have seen concerted efforts to integrate severe acute malnutrition (SAM) treatment into existing health services, including in complex, high-burden, low-resource settings.

What this article adds: Community management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) in Sudan has transitioned from a parallel humanitarian response to a government-led, integrated national programme that targets the total burden of malnutrition equitably across the country. An evidence-informed and planned expansion of services in the health system led to a fivefold increase in number of children treated (47,659 in 2010 compared to 230,000 in 2016), reaching half the total annual burden of SAM in Sudan, with geographic reach to non-emergency states. Local ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) production increased fourfold from 2013 to 2016. While still dependent on humanitarian funding, scale-up costs are increasingly met by government and development funding. Key factors for success included evidence-based decision-making; local level (bottom up) planning; early government engagement, leadership and ownership; strong technical support from UNICEF; solid leadership and coordination facilitated by a CMAM Technical Working Group; cost efficiencies of integrated versus vertical programming; and robust mentoring and monitoring systems. A dynamic interplay, rather than a shift between emergency and development risk-informed programming, has guided the scale-up approach.

Background

Sudan is the third-largest country in Africa in terms of landmass, with over 720,000 square miles hosting a population of over 40 million. Most of the eastern and northern parts of the country are part of the Sahara desert, characterised by sparse population and harsh environmental conditions, with some irrigable land along the Nile River. Effective service delivery is therefore challenged with sparse population and a poor infrastructure that is often distant from communities. In addition, the protracted conflict for over a decade in western and southern parts of the country, particularly in Darfur and Kordofan, have resulted in displacements and security challenges for effective healthcare delivery, generating major humanitarian needs.

Sudan was among the first few countries globally to adopt the outpatient treatment approach for treating severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in the early 2000s. However, services largely remained part of emergency responses supported by humanitarian actors and hence were confined to internally displaced populations (IDPs) and refugee camps for the better part of the decade. With closure of many non-governmental organisation (NGO) programmes in 2008/2009, capacity for SAM treatment dropped significantly and only started to increase again by 2011. When the first national survey of nutritional status, using S3M1, in late 2013 indicated that over half a million children were severely acutely malnourished, it triggered discussion on the need for a much faster and geographically wider scale-up of community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) response.

This article shares the experience of Sudan’s journey towards an integrated and accelerated CMAM scale-up over the past few years. It is a remarkable success story of scaling up in the context of ongoing complex emergencies, limited presence of NGOs and low health sector financing; and leveraging short-term humanitarian funding to support scale-up while strengthening health systems in the absence of longer-term development funding. While the efforts for accelerated scale-up encompass both SAM and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) management, this article focuses on the SAM component in order to describe the story clearly and in depth.

Planning for scale

Success starts with good leadership and team work

To lead national efforts on CMAM programming, in 2010 the Ministry of Health (MoH) established a CMAM technical working group (TWG) headed by Dr Ali Arabi from Khartoum University, supported by the CMAM unit in the Nutrition Department of the MoH and with active participation of UNICEF, the World Food Programme (WFP), the World Health Organization (WHO) and NGO partners. Under the leadership of the Director of Nutrition, Salwa Sorkatti, in consultation with the TWG, scale-up plans were developed, technical guidance formulated and implementation actions undertaken. Besides its role as co-lead with MOH for the nutrition cluster, UNICEF also provided significant support to the TWG, including technical and financial support for the S3M survey, evidence-based planning for the scale-up, procurement of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) and the implementation of the CMAM programme, particularly with respect to the treatment of SAM.

Failing to plan is planning to fail: Evidence-based planning from the bottom and up

After years of limited information on the scale of the nutrition problem in Sudan, the S3M survey undertaken in 2013 highlighted a prevalence of acute malnutrition above the 15% emergency threshold in 54 out of 184 localities across Sudan; a total burden of more than two million acutely malnourished children nationally, including half a million severe acutely malnourished children. Yet the capacity to treat SAM (and MAM) in 2013 was relatively low, focused only on states with complex emergencies. Results of a concurrent evaluation of the CMAM programme in 2013 emphasised the lack of a coherent plan for scaling up across the country as one of several key gaps (Tanner and Walsh, 2013). Based on these results, the MoH, together with the national CMAM TWG, embarked on the development of a costed CMAM scale-up plan. Planning workshops were held in each of the 18 states in Sudan where the nutrition officers and the maternal and child health (MCH) officers from each locality were supported to use the information from the S3M survey to prioritise hot spot areas in their locality. The locality-level planning contributed to state plan development and finally the national CMAM scale-up plan, based on meetings with the respective state heads of nutrition and close collaboration by members of the CMAM TWG to refine and finalise the plan.

The prioritisation dilemma - equity or burden?

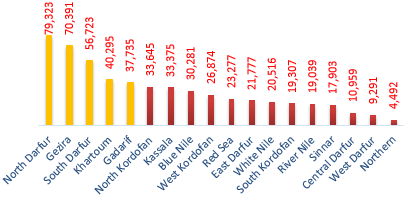

Two of the top five states with the highest caseload of SAM, accounting for half the overall SAM burden (Gezira and Khartoum), were states not considered to be in any emergency (see Figure 1). While Gezira state had the second-highest burden of SAM, there was no CMAM programme as it was not among the internationally supported states for emergency nutrition response. Hence, a major debate started on whether to prioritise states based on SAM prevalence or based on the absolute number (burden) of SAM children to maximise number of lives saved. Donor support has traditionally focused on areas of Darfur, Kordofan and eastern Sudan, where prevalence of acute malnutrition is relatively high. This was one of the key factors which led the MoH to step in and mobilise domestic resources to cover the high-burden states (as well as high-prevalence states) and ensure universal availability of CMAM treatment across Sudan. Between 2015 and 2016, the government contributed USD10.8 million in cash to the scale-up of CMAM, which is estimated to cover about a quarter of the overall cost for supply, training, mass screening and monitoring activities. When human resource and other health system costs are considered, the overall MoH contribution is 50% or more.

Figure 1: Five states with the highest burden of SAM in Sudan

Increasing the coverage of the programme

As part of the CMAM scale-up plan, key barriers for attaining sustained high treatment coverage were identified as distances to services, weak supply chains, overly complicated tools and procedures, weak linkages with health facilities and low awareness of malnutrition by communities (see Box 1). These were further analysed and discussed in detail and opportunities for improvement were identified. Subsequently, development of new or improved tools, training materials and protocols was undertaken with effort to address these anticipated bottlenecks for sustained high coverage, as well as to capitalise on the opportunities presented within the Sudanese health system, including the potential for CMAM integration with treatment of common illnesses at family health-unit level (see Figure 2). Mass mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) screening twice a year was also adopted as the key approach to early case finding, complemented by routine screening exercises in localities supported by NGOs.

Figure 2: Number of functional health units providing nutrition services in comparison with health units providing treatment for common illnesses

Box 1: Key challenges for attaining sustained, high-treatment coverage for acute malnutrition as reflected in the CMAM scale-up plan (January 2015)2:

- The scale of SAM: Over half a million children aged six to 59 months are estimated to be severely malnourished. This necessitates very fast scale-up of CMAM to as many health facilities as possible. However, the pace of scale-up depends on many factors, including finance, the number and composition of health workforce at the lowest level of primary healthcare (PHC), supplies, and delivery of required technical skills for the health workers.

- Complex emergency: The prevalence of malnutrition varies from state to state in Sudan. Some of the most affected states are also affected by protracted conflict. This results in limited access to some high-burden areas due to security constraints.

- Role of the health workers: While management of SAM is a common practice in paediatric wards after the children have developed clinical complications late in the course of the illness, it is not usual for the PHC-level health workforce to routinely diagnose and treat SAM. The CMAM evaluation indicated that outpatient treatment (OTP) is currently not well integrated into PHC. In large part this is due to nutrition being implemented as a separate activity and by nutrition staff rather than health workers. When malnutrition rates are high, local or international NGOs may set up emergency nutrition response in the localities affected by a complex emergency. This may have contributed to the perception that treating malnourished children is not part of the responsibility of the health worker. Such misperceptions need to be corrected as a child with SAM has the same right to treatment as any other child with common illnesses. The health worker responsible for treatment of common illnesses should make sure that all children are treated for common illnesses, including malnutrition.

- The link between nutrition and medical staff at facility level: In MoH-operated inpatient sites, the nutritional protocol was followed, albeit inconsistently, as per the CMAM evaluation undertaken in 2013. The same MoH nutritionists who manage OTPs are also managing inpatient care. There is little link between the nutrition staff and medical staff. As a result there is inadequate linkage between the nutritional and medical management of cases and little nursing care in many sites. In many stabilisation centres (SCs) visited, there was no nursing supervision during the night. Mothers were left to prepare milk themselves.

- The need for further decentralisation of services: The existing health facilities are frequently not within a 5 km radius of catchment communities. This means that many families have to walk for more than an hour to access services, even for outpatient treatment. This contributes to later presentation whereby families come for treatment only when children are seriously ill.

- The link between health service delivery and the community: As indicated in the Maternal and Child Health (MCH) acceleration plan3, the high number of communities and low number of community health workers has contributed to a gap in the available services in the health system and their utilisation. A generic CMAM community mobilisation strategy is currently under development in Sudan4. This strategy is meant to serve as a tool for all community mobilisation of MCH services through better linkage of health facilities and communities, building on existing community level initiatives.

- Maintaining a smooth supply pipeline: CMAM supply management is highly complex and, at times, the rate limiting factor for CMAM scale-up. The weight and volume of supplies for treatment of malnutrition are bulkier compared to those for other common illnesses. The supply systems and structures of the health sector do not often have adequate storage space, particularly at the lowest levels. In addition, and related to this, delivering supplies from locality to health facility level is often a challenge, resulting in stock outs.

- Cumbersome tools and procedures in OTP management of SAM (Collins et al, 2006): Based on the 2013 CMAM evaluation recommendation, simplified tools and protocols are needed to treat early-stage SAM in the community. This is to ensure simple doable actions to the users, limiting non-essential information to the extent possible.

Marching towards better capacity at scale

From task-shifting to task-sharing in the treatment of SAM

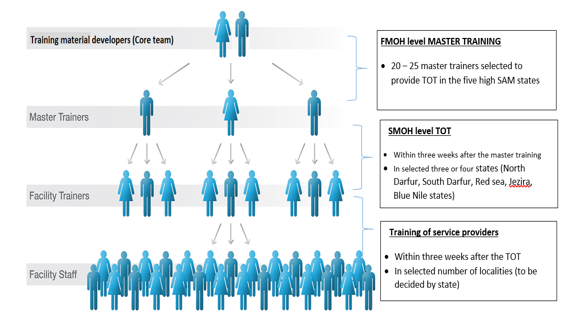

Severely malnourished children in Sudan primarily received treatment from a lower level of cadres (nutrition educators), rather than medical assistants; CMAM treatment was regarded as a separate nutrition intervention outside their responsibility. Nutrition educators have insufficient clinical training or experience, increasing risk of case mismanagement, and this approach is unsustainable. It was recognised that big gains can be achieved for CMAM by integrating case management of SAM into treatment of common illnesses so that the medical assistant, or other clinicians in charge of a facility, would actively lead the management of all sick children, including malnourished children, and decide on the appropriate course of action and follow-up by the wider health facility team. This policy decision was endorsed by senior health managers at national and state level. Accordingly, a training model was developed (see Figure 3) to equip health workers quickly at scale so that the task of managing a severely malnourished child was shared, from the least clinically skilled nutrition educators in most rural health facilities to the medical assistants supported by the nutrition educators during weekly follow-up.

Figure 3: CMAM training cascade model for rolling out CMAM training in Sudan

Development of simplified tools - simple to the end user, not so simple to devise

While treating uncomplicated SAM in the early stages is relatively easy, treating a severely malnourished child with complications who has presented late is complex and requires a higher level of skills (Collins et al, 2006). Hence, based on the 2013 CMAM evaluation recommendation, the TWG commenced on the development of simplified tools and protocols to treat early stage SAM in the community or at lowest levels of health facilities. This aimed to provide simple, doable actions to the users, limiting non-essential information to the extent possible.

Several consultative meetings were held in late 2014 where the TWG reviewed in fine detail the simplified materials drafted by members. Operational guides for outpatient management of severely and moderately malnourished children were developed as small pocket books (A5-sized) and translated into Arabic. These were then endorsed by the senior paediatricians in Sudan.

The rollout of training and transfer of skills using the tools were key considerations as the materials were developed. The training sessions used the operational guides as participant reference, so that every trainee was familiar with her/his pocket reference. A facilitator guide was developed using adult learning principles (only one introductory PowerPoint presentation). A snapshot of each of the materials developed and used in Sudan can be found in Box 2.

Box 2: Simplified tools and materials developed for CMAM scale-up in Sudan in late 2014 and early 2015

Name of document Description National plan for scaling up CMAM in Sudan National plan for scaling up CMAM in Sudan Operational guide for OTP management of SAM - Feb 2015 This operational guide was officially launched by the under-secretary of the MoH. This reference material is distributed to each of the under-five clinics or OTP sites that manage uncomplicated SAM. It was developed in English and translated into Arabic and is used as a pocket quick reference during service delivery and as a participant reference material in the training rollout. Facilitator guide - management of acute malnutrition at PHC level - Feb 2015 Developed in English, used to train health workers/nutritionists in the three master trainings and subsequent TOTs and service-provider trainings. It has a facilitator guide translated into Arabic to facilitate lower level training rollout. PowerPoint presentations are avoided and the material is used as a step-by-step guide for participatory adult learning through facilitation. Operational guide for management and prevention of MAM - Feb 2015 Developed in English, translated into Arabic and used as a participant reference material in the training rollout. This is a similar guide as the one for OTP, with a similar purpose. For ease of reference and use, the guides were crafted as two separate pocket reference materials in Arabic. Operational guide for community engagement This was drafted following the consultative workshop 19-20 August 2015. The community mobilisation model, called Jabana model, was developed and fully adopted in Kassala, Gedarif and Red Sea states. In addition, use of mother support groups (MSGs) to undertake MUAC screening was adopted by Kordofan, Darfur and eastern states in Sudan. Joint nutrition mentoring score card This is a score card developed in 2015. Consultants were recruited and deployed to mentor the health facilities providing CMAM (both newly open and existing). Score cards were updated further in 2016.

Rollout of training and expansion of service provision

In the first half of 2015, two master trainings were undertaken at national level followed by state-level training of trainers (TOTs). As per the cascade training conceptual model (see Figure 3 above), this was followed by locality-level service-provider trainings in the second half of 2015. Members of the TWG and master trainers were assigned to support and oversee each of the lower level trainings for quality assurance. The last day of training was used to plan the next course of action. For instance, at the end of the training, the TOTs were grouped by locality to plan the date and venue of the service-provider training. Similarly, the last day of the service-provider training was used to plan the date for starting CMAM services in their respective facilities. For example, service providers were requested to outline the support required while the organising team, together with MoH and UNICEF, used this information for subsequent follow-ups to ensure that the requested inputs were received.

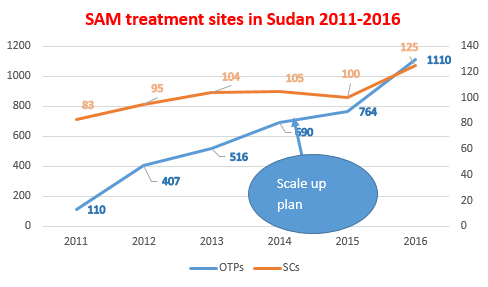

Through the cascade training, 115 master trainers, 395 TOT, and 2,761 service providers were trained covering all states in Sudan. Based on the training and the immediate, context-specific detailed planning, an additional 420 new OTPs were opened in 2016, a significantly higher number than 2015 and comparable to the total number of sites opened in 2012-2014 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Number of sites offering CMAM services in Sudan

Strengthening health facility - community linkages

With the sparse population and harsh environmental conditions in Sudan, health-seeking behaviour is relatively low and expanding the availability of services has not resulted in a comparable utilisation of services. Similar observations have been documented by the Coverage Monitoring Network in many other settings, where the decentralisation of care improved availability but did not ensure accessibility (Guerrero and Rogers, 2013). Thus, several efforts were made to improve demand for services. These include development of a model for community mobilisation (called Jabana model5), biannual mass screening and use of mother support groups (MSGs) to undertake MUAC screening. Several approaches have been used in various combinations as different communities have different contexts and one approach does not work everywhere. The MSGs were effectively used in Darfur states, Kordofan states and Kassala in conjunction with mass screening. Jabana model was particularly effective in eastern states, especially in Kassala. The Government of Sudan invested significantly in mass screening activities as the CMAM community component required time for communities to understand, and in the meantime the target numbers of SAM were not being reached adequately. Mass screening activities undertaken in August and September 2016 reached 4.3 million children aged 6 to 59 months out of an estimated 6.8 million children in Sudan (70.2%). Children identified as malnourished were linked immediately with the newly expanded CMAM services for treatment.

Shift from emergency focus to long-term, risk-informed programming for CMAM

Increased government investment for CMAM

As the owner of CMAM programmes that are implemented within the health system, the MoH contributed to all aspects of CMAM costs, including programme costs (human resource, training and M&E); health-system costs (hospitals and health facilities costs); and treatment inputs (therapeutic feeds and drugs) as part of the MCH acceleration towards universal healthcare coverage to reduce child and maternal mortality. Before 2015, the government contribution towards CMAM was minimal as relatively few government facilities were treating SAM children and the cash allocation to CMAM supplies and monitoring was also low. This has changed markedly in the past few years, evidenced by the increasing cash allocation and the absorption of administrative costs as many more MoH facilities integrated the treatment of SAM. Since no CMAM costing exercise has been undertaken in Sudan recently, only direct cash investments are shown in Table 1 as an example of increasing investment from government.

Table 1: Cash contribution of MoH towards CMAM in the period 2016/2017

| Government cash contribution to CMAM (USD) | Description | |

| 2016 | 1,669,422 | For RUTF, RUSF and screening |

| 2017 | 9,187,248 | For RUTF, RUSF, F100, F75, anthropometrics (MUAC tapes, weighing scales), nutritional screening and operational costs |

| Total | 10,856,670 |

Public-private partnership for improved RUTF supply chain

The scale-up saw a rapid expansion of the volume of RUTF, which overwhelmed the warehousing and transportation systems at national and state levels. Through a private partnership with UNICEF, a local producer (SAMIL) established five storage hubs in emergency hot-spot areas, in addition to an existing one in Khartoum, and pre-positioned RUTF supplies for timely access. Moreover, the local producer was willing to produce without an order in hand, allowing forward planning even when there were no funds immediately available. This resulted in significant reduction in the lead time for RUTF delivery to the states by up to three months, saving the time of production, custom clearance, and transportation to state level where some states require security clearance.

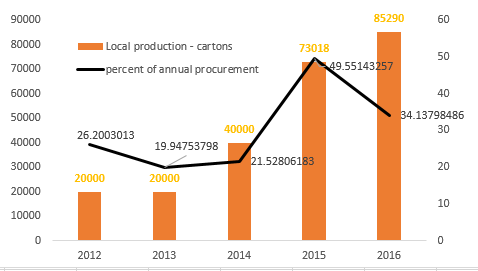

Between 2013 and 2016, the contribution of local RUTF production for CMAM in Sudan grew fourfold (see Figure 5). This is likely due to the growing and more reliable institutional market and investments in local production capacity. While absolute cost of local versus international supply is currently higher, there are additional benefits; local production stimulates local jobs and markets, providing additional incentive for government contribution, and should save cost and time in the long term. The local producer, SAMIL, has successfully negotiated with the government on removal of value added tax (VAT) on RUTF, which has led to significant reduction in the price of RUTF and has made local procurement more cost effective.

Figure 5: Contribution of local RUTF production in Sudan6

Real-time monitoring for results

There was recognition that the effectiveness of cascade trainings is very limited unless followed by intensive mentoring and supportive supervision. A core monitoring team was established at state level composed of MoH, UNICEF and NGO partners where they were present. Based on discussion with the MoH, UNICEF recruited experienced nutritionists to support the state monitoring teams in providing high-quality mentoring and monitoring, targeting facilities offering CMAM services, particularly in high-prevalence and low-capacity localities. The objective of real-time monitoring had been to strengthen the correct application of the national guidelines for the management of SAM. Hence, in addition to support for individual case management, it included support to strengthening current reporting, supervision, community mobilisation and supply management systems within the MOH.

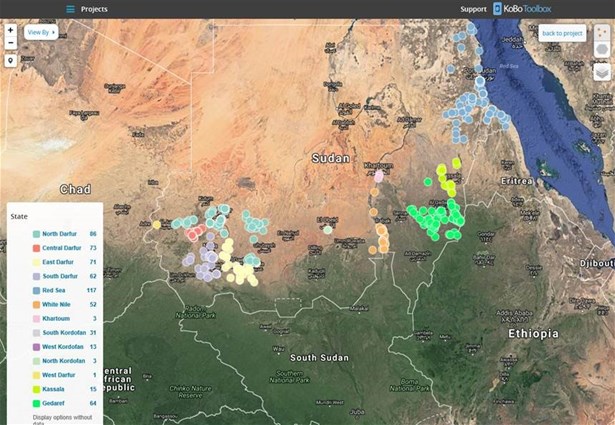

UNICEF adopted the Kobo toolbox in 2015 to enhance the monitoring activities. Kobo toolbox applies smartphone technology, allowing real-time access to information by multiple users, hence providing real-time data on monitoring findings, and allows timely remedial action and response where necessary. Kobo also provides spatial maps on overall coverage of monitoring of interventions (see Figure 6) and has improved accountability of individual contractors engaged for monitoring, as well as donor confidence in the reliability of monitoring systems for CMAM.

Figure 6: An example of a spatial map generated by Kobo showing number of sites visited during CMAM monitoring in 2016

Kobo has been used in 969 facilities with OTP out of 1,110 in 13 states (about 87% of all OTP sites). Looking at the encouraging results from UNICEF support to Kobo in areas with complex emergency, the MoH has decided to adopt the approach nationwide, including both the standard score cards and Kobo. This will further increase the coverage of monitoring. The ministry is planning to have three levels of monitoring:

- National-level monitoring: through the national CMAM team or the national TWG member(s);

- State-level monitoring: each state has a dedicated CMAM coordinator to monitor locality implementation; and

- Locality-level monitoring: each locality has a locality focal person to monitor implementation at the centre levels.

Strong information system

The CMAM database is a key component of the nutrition information system in Sudan. It allows states and the national MoH to monitor progress on the number of facilities newly offering SAM treatment and the actual number of SAM admissions against the target in the national scale-up plan on a monthly basis. This has allowed focused efforts for scale-up and community mobilisation in localities that were falling significantly short of targets.

Reflections and lessons learned

Bridging the humanitarian-development nexus

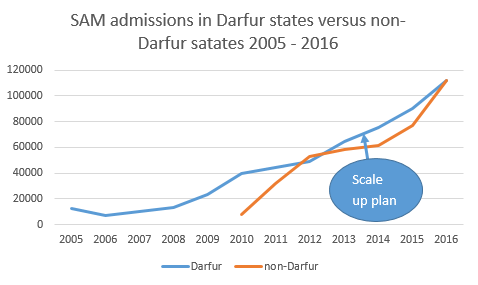

On closer look at the states contributing to SAM admissions, a progressive shift from short-term, emergency-focused and internationally led CMAM programming to a longer-term, government-owned and led national CMAM programme which is more closely integrated within health service delivery can be seen. Prior to CMAM scale-up plan in 2015, the SAM admissions in non-Darfur states were plateauing because of limited investment. CMAM scale-up as per the national scale-up plan resulted in increased SAM treatment availability in non-Darfur states through integration within the health service delivery platform. States considered non-emergency like Gezira, Northern and River Nile states went from virtually no functioning CMAM programme prior to mid-2015, to treating over 9,200 severely malnourished children in 2016 alone (see Figure 7). This has been achieved because of government investment to procure supplies and for training rollout as humanitarian funds do not cover these states. In addition, the Government of Sudan invested significantly in mass screening on a biannual basis, progressively increasing the non-emergency contribution to CMAM programming.

Figure 7: SAM admissions in Darfur states versus non-Darfur states

While recognising the progressive geographic spread of CMAM in Sudan, it is important to acknowledge that the scale-up of CMAM, including the investment in the supply chain and monitoring system, has largely been supported by humanitarian funding with increasing government contribution and non-emergency funding. As Sudan invests in CMAM scale-up as an example of risk-informed programming, the emphasis is not so much on a shift from emergency to "development" programming, but rather an ongoing and constant interplay between development and emergency considerations, resulting in a sufficient investment to improve the capacity of health systems to be effective and efficient.

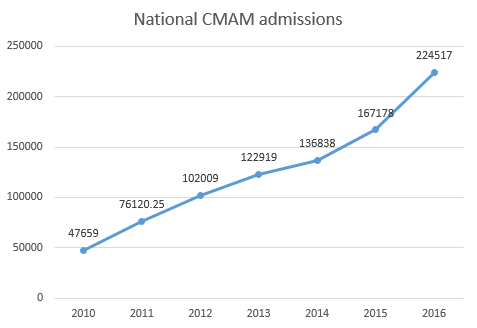

Due to ongoing CMAM scale-up efforts as part of routine services, the number of children accessing treatment at all times has increased significantly. For example, in 2016 alone, a total of 224,517 children received treatment for SAM through the national CMAM programme. This represents an additional 57,400 children receiving treatment for SAM compared to 2015, which is more than the total number of children treated in Sudan in 2010 (47,659) (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Annual admission for management of SAM in Sudan

There are several key success factors for CMAM scale-up in Sudan (see Box 3). The approach was built on evidence based, bottom-up planning led by government with strong technical support and coordination arrangements. In addition, CMAM scale-up in Sudan is the result of concerted efforts of all organisations working in nutrition with government. This has resulted in efficient and effective expansion of access to service delivery that was augmented through community mobilisation and mass screening. CMAM programming has effectively transitioned from a parallel humanitarian focus to an integrated, government-led programme. The approach has been to get CMAM at a sufficient scale to be meaningfully integrated within the treatment of common childhood illnesses in every health facility, including integrated management of neonatal and childhood illnesses (IMNCI) and integrated community case management (iCCM). The lessons from CMAM scale-up will contribute to the overall improvement of availability and access to treatment of common childhood illnesses. Thus, CMAM presents an excellent opportunity for the Sudan health sector as a step towards universal health coverage.

Box 3: Lessons learned on key success factors for CMAM scale-up

Evidence-based decision making: The need for scaled-up response was evidence-based. The national S3M study as well as the CMAM evaluation, both undertaken in 2013, heavily informed key actions for scale-up. In addition, a roadmap document was prepared as part of the scale-up planning process that presented analysis of the health system opportunities for integration with compelling evidence for task-sharing. The nutrition information system allowed tracking of admissions against targets, as well as treatment outcome indicators so that sufficient coverage is reached with optimal quality of service.

Bottom-up planning: The scale-up plan followed a bottom-up planning process whereby each of the 18 state MoHs held CMAM scale-up planning workshops. The plans were later revised at opportune times, enabling maximisation of the opportunities presented by the healthcare delivery platform through integration. This improved the ownership at sub-national level, allowing for implementation of the new directive on task-sharing in the treatment of SAM.

Government leadership and ownership: Every step of the CMAM scale-up was undertaken with strong engagement and leadership of the MoH. Both the S3M survey and CMAM evaluation were undertaken with full ownership of the MoH, hence follow-up actions were strongly owned and led by the MoH. The federal MoH led the consolidation of the national plan and the development of all relevant tools. It also allocated resources for implementation and monitored the implementation of the CMAM scale-up against the plan. The state MoHs organised planning workshops and later followed through the plan to make it a reality through supporting localities and facilities.

Strong technical support from UNICEF: The UNICEF Sudan office provided significant financial and technical support that facilitated government’s efforts for scaling up. In addition to supporting both the S3M study and CMAM evaluation financially, UNICEF facilitated recruitment of consultants to provide technical support to the state-level planning exercise, on-job training and supportive supervision. A full-time technical assistant was recruited to work closely with the MoH to enable finalisation of the nationwide plan, development of required technical tools and materials, and support the implementation of scale-up. All of this was possible because of donor investment to complement government efforts.7

Strong leadership and coordination: The CMAM TWG was used as a convening body for overall leadership and technical oversight of the CMAM scale-up process. Since the complex emergency has inevitably resulted in a complex relationship among various partners, the TWG played a vital role in providing technical leadership, as well as coordinating all partners to reach a common consensus.

Cost efficiency: The shift from vertical planning of CMAM scale-up to a harmonised and integrated approach has enabled major cost savings; treatment of SAM has been taken up by existing health workers as part of curative services to be offered in their facilities.

Well structured training and skill support: The training rollout was cascaded at a rapid and pace and organised manner, enabling sufficient capacity of service providers in a short space of time. Simplified pocket reference material was used as participant guide for all levels of training that remained in use during service provision. Immediate mentoring action was in place to allow supportive supervision and skill support on the job.

Strong mentoring and monitoring system: The availability of a strong and accountable mentoring and monitoring system has been key to ensure quality while scaling up. Use of technology has enabled real-time support and follow-up to address gaps as they arise.

The findings, interpretations and conclusions in this article are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of UNICEF, its executive directors, or the countries that they represent and should not be attributed to them.

For more information, contact: Mueni Mutunga, email: mmutunga@unicef.org; or Tewoldeberhan Daniel, email: tdaniel@unicef.org or Hanaa Garelnabi, email: hanaakusu122@gmail.com