Accountability to affected populations: Somalia Nutrition Cluster experiences

By Samson Desie and Meftuh Omer Ismail

Samson Desie is a nutrition specialist currently working as Nutrition Cluster Coordinator in Somalia with UNICEF. He has over 10 years’ experience in managing large-scale and complex programmes in grassroots, national and international contexts, including in the South Sudan crisis situation, Sudan protracted emergency and Somalia.

Meftuh Omer Ismail is a Senior Nutrition Technical Specialist for Save the Children Somalia, a position he has held since 2016. He has previously worked as a Nutrition Programme Manager for Save the Children South Sudan and Nutrition and Health Coordinator for Merlin in South Sudan and Ethiopia.

The authors would like to thank the Federal Ministry of Health Somalia, UK Department for International Development (DFID), World Food Programme (WFP) and Save the Children International (SCI) in Somalia. A special acknowledgment goes to Paul O’Hagan, Humanitarian Advisor for DFID Somalia, for his review, guidance and support during the development of this paper.

The findings, interpretations and conclusions in this article are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of UNICEF, its executive directors, or the countries that they represent and should not be attributed to them.

This field article is based on a presentation made by Samson Desie, supported by ENN, at the annual Global Nutrition Cluster (GNC) meeting in Amman in October 2016 and subsequently updated mid-2017 by Samson and key stakeholders.

Location: Somalia

What we know: Accountability to affected populations (AAP) is a key Nutrition Cluster function, reflected in five commitments (leadership/governance; transparency; feedback and complaints; participation; design, monitoring and evaluation).

What this article adds: “Weak” AAP, identified in a Nutrition Cluster evaluation in 2014, prompted revitalised coordination and a systematic approach to address weaknesses. Since 2015, the Somalia Nutrition Cluster has led development and promoted adoption of an AAP framework. Three levels of accountability around AAP in Somalia have evolved: large-scale (led by WFP), moderate-scale (led by Save the Children) and a minimum level (access to cluster-controlled pooled funding is contingent on this). There is increasing donor buy-in, including by DFID. Community conversations have been introduced in almost all emergency service delivery units/areas. A comprehensive online platform on monitoring and evaluation has integrated AAP for imminent launch; programme quality, coverage and performance will be tracked and transparent. Complaints are investigated by the cluster in a consultative verification and resolution process. Since May 2017 OCHA Somalia, alongside clusters and partners, has implemented Common Feedback Project (CFP) for APP in prevention of famine. Looking ahead, AAP is mainstreamed in the Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) cycle to facilitate uptake.

In 2014, the Somalia Nutrition Cluster (SNC) performance evaluation found that accountability to affected populations (AAP), a key cluster function, was “weak”. A consultative workshop was organised in June 2015 to revitalise the coordination mechanism and identify a more systematic and integrated approach to address all weaknesses (Desie, 2016), acknowledging the traditional accountability mechanisms between and among communities in Somalia which are mainly through clan leaders/elders and sheiks. A new way of working was agreed, centred on ensuring AAP through coordinated and inclusive systems. The Somalia Nutrition Cluster Coordinator (SNCC) considers AAP a central element of its Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) (as described by the five commitments to AAP displayed in Box 1). Sparked by developments in 2015, the SNCC has been working to ensure that all cluster partners adopt an AAP framework. Experiences since then are shared in this article.

Box 1: Commitments to accountability to affected populations (CAAP)

Agreed by the Interagency Standing Committee (IASC) in December 2011, the five commitments to accountability to affected populations (CAAP) are:

1. LEADERSHIP/GOVERNANCE: Demonstrate their commitment to accountability to affected populations by ensuring feedback and accountability mechanisms are integrated into country strategies, programme proposals, monitoring and evaluations, recruitment, staff inductions, trainings and performance management and partnership agreements, and highlighted in reporting.

2. TRANSPARENCY: Provide accessible and timely information to affected populations on organisational procedures, structures and processes that affect them to ensure they can make informed decisions and choices and facilitate a dialogue between an organisation and its affected populations over information provision.

3. FEEDBACK and COMPLAINTS: Actively seek the views of affected populations to improve policy and practice in programming, ensuring that feedback and complaints mechanisms are streamlined, appropriate and robust enough to deal with (communicate, receive, process, respond to and learn from) complaints about breaches in policy and stakeholder dissatisfaction. Specific issues raised by affected individuals regarding violations and/or physical abuse that may have human rights and legal, psychological or other implications should have the same entry point as programme-type complaints, but procedures for handling these should be adapted accordingly.

4. PARTICIPATION: Enable affected populations to play an active role in the decision-making processes that affect them through the establishment of clear guidelines and practices to engage them appropriately and ensure that the most marginalised and affected are represented and have influence.

5. DESIGN, MONITORING AND EVALUATION: Design, monitor and evaluate the goals and objectives of programmes with the involvement of affected populations, feeding learning back into the organisation on an ongoing basis and reporting on the results of the process.

https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/accountability-affected-people

AAP in Somalia: levels of accountability

Until 2016 the World Food Programme (WFP) and Save the Children International (SCI) were the main agencies working in Somalia with a fully adapted AAP framework, although other cluster partners were beginning to follow suit. Three levels of accountability around AAP in Somalia have evolved: large-scale, moderate-scale and a minimum (mandatory) level. The distinctions between these levels are as follows:

Large-scale

This has been achieved by WFP through the use of call centres (hotlines/phone lines) and interactive voice response/recording (IVR). This approach involves a substantial number of staff, a wide scope of activity and coverage and is decentralised through regional service delivery areas. The IVR has two main functions: surveys and complaints. IVR (complaints) provides pre-recorded, interactive beneficiary support outside working hours through call centres to deliver information on WFP programmes, sensitisation on health and nutrition issues and the chance to record a question or complaint for WFP to call back and answer. IVR (surveys) involves pre-recorded, interactive, short surveys to beneficiaries using outgoing calls. These can be used to collect information on awareness, food security, access to nutrition services and acceptability of the WFP feedback and complaints mechanisms for respondents who cannot read. Hotline call centres and IVR questions and complaints are managed by professionally trained operators, experienced in handling calls from beneficiaries and the general public. Systems in most areas are supported with dedicated, full-time staff. The system covers ‘hot spots’ and obtains information on geographic coverage of the programme and numbers of staff and exit interviews. Messages are sent using bulk short text messages (SMS).

WFP has incorporated a two-to-three-step verification process of complaints in its AAP system to identify whether issues raised are important or trivial. Some issues are discarded after two to three case investigations, while others, such as questions around cash/voucher/food distribution, require follow-up action. WFP takes the need to rectify problems and ensure that services are delivered as planned very seriously. The feedback mechanism is still being developed and does not yet provide a complete loop. However, AAP information is being acted on and WFP has modified programming as a result of beneficiary feedback found to be credible and/or valid.

Moderate-scale

SCI has adopted this approach. Its main component is an online facility and it operates in just a few sites. There are random checks on beneficiary experiences by programme staff in routine monitoring and evaluation (M&E), activities, but no dedicated, separate staff. This system is known as MEAL (monitoring, evaluation, accountability and learning) and operates within SCI both at the global and Somalia level. The MEAL framework resonates with the SCI quality framework1, which puts M&E, accountability and learning at the heart of programme quality, together with technical excellence and evidence base. SCI’s approach is detailed in Box 2.

Minimum (mandatory) level

All SNC partners are required to adopt this minimum level of AAP; pooled funding secured via the SNC, mainly via the Somalia Humanitarian Fund (SHF) (formerly the Common Humanitarian Fund (CHF)), is contingent on this. This approach involves exit surveys with those discharged from programmes and with defaulters.

Box 2: SCI’s approach in ensuring AAP

SCI believes that real accountability to children and communities affected by crises involves giving them not only a voice but also the opportunity to influence decisions affecting them and holding the organisation to account by influencing SCI’s policies, priorities and actions at local, national and global levels. Accountability is part of SCI’s core values and is a main component of the organisation’s quality framework and management operating standards. SCI ensures APP with its beneficiaries through various approaches, including:

– Complaints feedback response system (C/FMS): Established by SCI, this comprises hotlines/toll-free numbers, focus group discussions, complaints desks and random proactive calls/SMS to programme/project beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries. Random proactive calls/SMS involves systematic listening and setting up formal mechanisms in intervention areas for people to express views and concerns on SCI’s approach, activities and impact, as well as on safety issues and the behaviour of SCI staff. In addition, beneficiaries from the health and nutrition service have an exit interview once they finish the cycle of support to get feedback on the service.

– Translation of project documents: All SCI programme/project key information is translated into local languages, printed and posted in community gathering places. This communicates information on beneficiary targeting, beneficiary entitlements, complaint response mechanisms, project duration, donor and platforms for community participation in implementation of the project activities. There are also random checks and calls on beneficiaries to find out whether they have received their entitlements.

– Developing and printing programme accountability standards: These are printed in illustrated form (for illiterate people) and in narrative form to explain what behaviour people can expect of SCI staff and representatives (in line with SCI’s child safeguarding policy and code of conduct), and how people can be involved and provide feedback and complaints.

– Use of accountability system feedback: SCI has developed an accountability database for all beneficiary and non-beneficiary complaints and feedback from its programmes. The information is analysed on a monthly basis and shared with the senior management team for discussion and decision-making to adjust programme activities in response to the local context, proposal development and knowledge generation.

Training on AAP – community conversations (CC)

The SNC implemented training in Somalia to help incorporate AAP into community management of nutrition. The concept of community conversations (CC) was introduced to all partners with the understanding that it was to be implemented in almost all emergency service delivery units/areas. This is mainly being achieved through the adoption of two key communication approaches in every personal/interpersonal communication with beneficiaries (i.e. negotiation with caretakers) and in group conversations/dialogues.

Negotiations with caretakers involve two key steps, GALIDRAA and ORPA. These are acronyms for the first letter of part of the intended communication. ‘GALIDRAA’ stands for Greet the mother/caretaker, Ask the mother, Listen to the mother, Identify current nutrition or care practice and any problems and challenges to taking action on optimal practices, Discuss different options to overcome any challenges, Recommend and negotiate actions, Agree, and make an Appointment for a follow-up visit. This approach is supported using visual aids, guided by the acronym ‘ORPA’: have the caretaker OBSERVE the illustration, REFLECT on what they see, PERSONALISE/put themselves in the situation and see if they are willing to ACT on what they have seen and discussed.

CC is an ongoing process of facilitating and enabling community group to meet regularly to identify and reflect on its problems and their root causes; analyse and build consensus on possible solutions; develop community action plans; secure the necessary human, material, information and financial resources; and take collective actions at family, community and institutional levels that will lead to long-term, positive change. The main objective of CC is to generate an effective, community-based nutrition response to social/communal problems/issues that integrates individual and collective concerns, values and beliefs and that addresses attitudes, behaviors, practices and other underlying factors embedded in social systems and structures.

CC is a cyclical process that involves relationship building, problem identification, resource exploration and planning, reflection of process, action, intervention and problem exploration. These should not to be confused with traditional behavioural change communication (BCC)/ information, education and communication (IEC) activities: the whole purpose of the CC/community dialogue in the AAP is to avoid the BCC expert approach and instead focus on helping the community to assess its own situations/problems, questioning the ‘why’ in an attempt to analyse the causes and choosing prioritised courses of action to address the situations/problems identified.

Training in the use of CC began in 2015 and has since been integrated with all capacity development efforts, including nutrition in emergencies (NiE) training. The SNC has also given training in AAP in Hargeisa, Mogadishu, Bosaso and Nairobi as part of a larger programme of NiE training. Every outpatient therapeutic programme (OTP) is now expected to involve a CC to nurture a basic understanding of malnutrition and what the community can contribute to help address the problem. The aim is to make malnutrition visible to the population and broaden ownership of its management. There is now a community group in every service delivery area.

Using funding as leverage for AAP

Funding provided through the CHF since 2016 has been contingent on agencies having an AAP framework in their proposals. There has been resistance to the AAP from some partners who felt that the mandatory requirement was “too controlling” and that the AAP is effectively an audit mechanism. However, the cluster has managed to clear some misconceptions and convince an increasing number of partners of its merits. While cluster funding has provided leverage to make this happen, some partners have voluntarily bought into the AAP. Donors, such as the UK Department for International Development (DIFD), have shown great interest in the AAP and have encouraged the cluster to move forward with its development. DFID has cited the AAP as a means of ensuring accountability and transparency and is now implementing a third-party monitoring (TPM) system whereby DFID-funded partners must adopt an AAP as part of their overall monitoring. The new DFID Humanitarian Reform Policy2 has a strong emphasis on people’s right to participate in the decisions that affect them, for DFID to be more accountable to them and for them to make their own choices.

DFID continues to encourage and support the cluster, pushing for more innovative practice in the field, and appears to be learning from the Somalia experience and applying it to other country contexts.

The SHF has increasingly been used to invest in the scale-up of the AAP framework, especially the minimum package. In 2016 the SHF funded 11 partners, including five international, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and six local partners. From January to July 2017, 14 partners (eight local and six international NGOs) incorporating the AAP were funded and around $5.6 million dollars was invested by the fund in the pre-famine response. Through the SHF mechanism the SNC has played an important role in enabling national NGOs to access funding; approximately 60 per cent of SHF funding goes to local agencies.

Online platform incorporating AAP

In 2016 the SNC began work on a comprehensive online platform (ONA – https://ona.io/home/) that has an integrated component on AAP as part of a wider M&E system. The platform is being finalised; almost all components (except AAP) became operational and were officially released in July 2017. The platform will be fully functional in early 2018. This online development is being supported by UNICEF, WFP and DFID. The platform allows for geotagging of service sites, infrastructure assessment, and capacity assessment of service delivery facilities in terms of service provision and human resources. An integrated AAP framework links with beneficiaries and facilities and a contact database for beneficiaries allows complaints and a feedback mechanism (with comments via SMS). The platform covers planning and monitoring and reporting (M&R) on top of AAP.

Planning: Service plans are developed and thresholds for scale-up are agreed. Based on assessment results, planning takes place according to which areas have been identified for scale-up or where to consolidate services. Planning tools include:

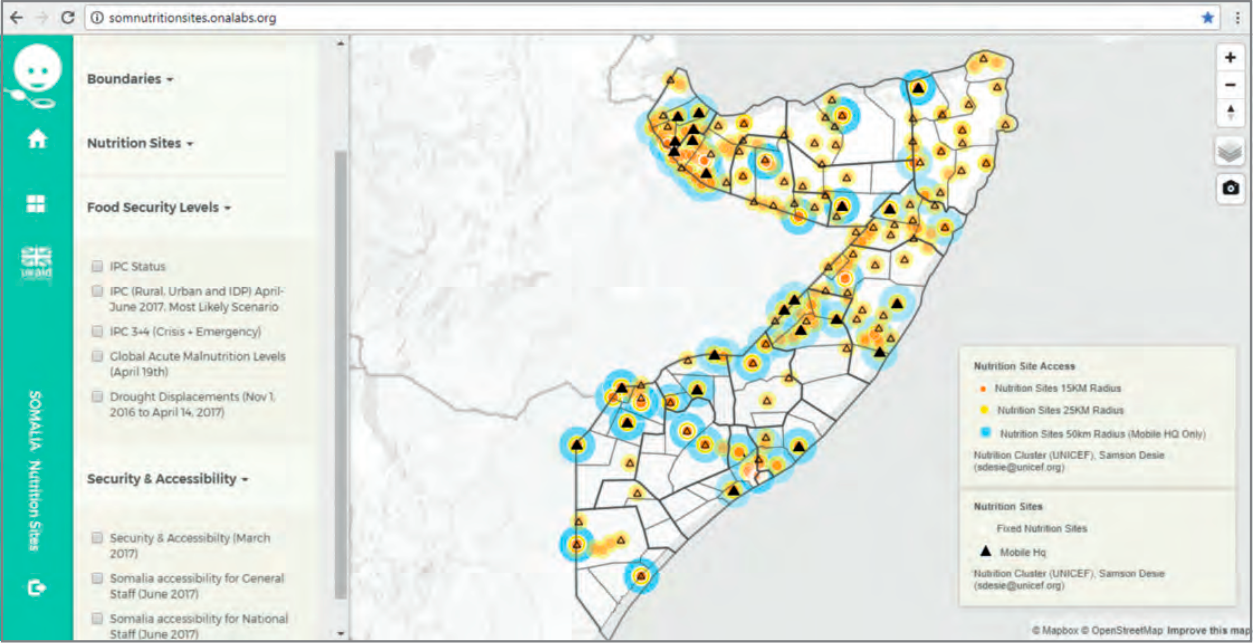

- Collaborative maps which can be overlaid with multiple sectors/clusters and refocus programming and responses based on objective analysis: http://somnutritionsites.onalabs.org/ (using password ‘ncs’ if required) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Screenshot of the collaborative map function on the SNC online platform

- Well-defined food security risk information that can be used to formulate comprehensive integrated management of acute malnutrition (IMAM) coverage/expansion plans.

- Validated information on service delivery sites and capacity that can be used to guide, consolidate and strengthen the existing capacity of emergency nutrition units across Somalia, develop overall emergency preparedness/resilience and help in the scale-up of IMAM.

- Immediate actions/steps that can be taken by all partners/organisations to improve standards of specific nutrition sites.

- Opportunity for partners to self-report on progress of nutrition sites (such as whether they are new, opened or closed).

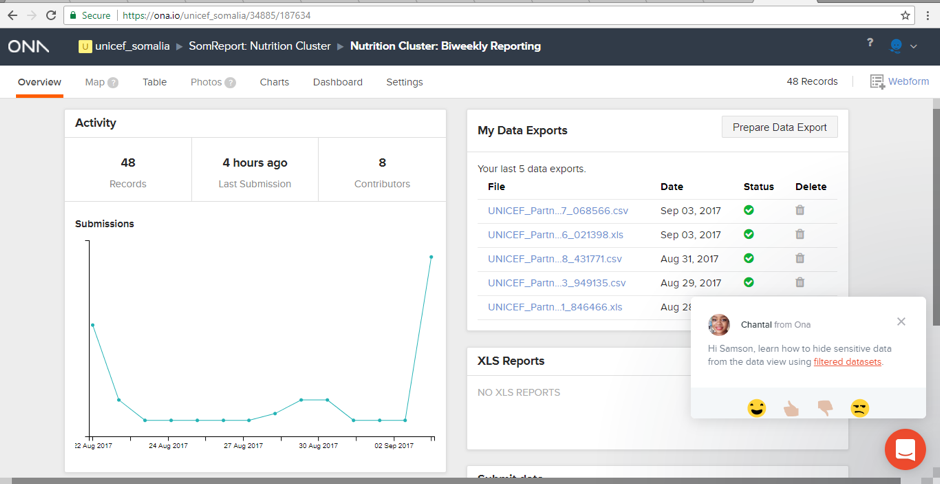

Monitoring and reporting: The online platform enables monitoring and reporting of partner activities and includes the following functions:

- The presentation of performance indicators in simple graphics, including a dashboard of performance indicators for each service delivery unit. Information is currently updated fortnightly to help monitor the performance of pre-famine scale-up and response.

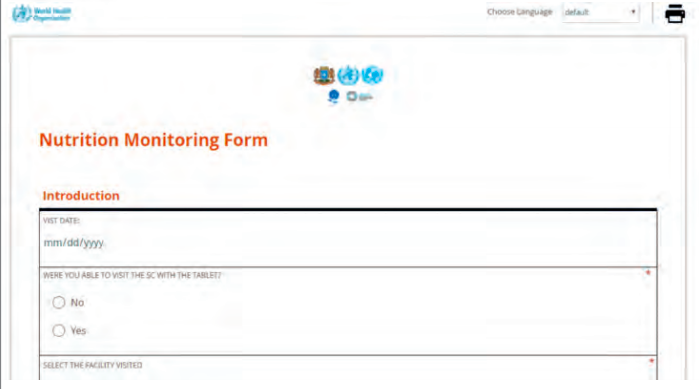

- Digital and automated upload of facility-level information using a standardised, user-friendly reporting form. This is available online via mobile/open data kit (ODK), SMS and off-line (Figure 2). All partners are assigned unique access to the system via the following links: https://ona.io/unicef_somalia/34885/187634 (for Somalia) and https://ona.io/unicef_somalia/34885/196108 (for Somaliland)

Figure 2: Screenshot of the online nutrition monitoring form

https://enketo.aws.emro.info/x/#YYYy

- A standard online monitoring framework that allows monitoring of the combined activity of all partners while maintaining confidentiality.

Figure 3: Screenshot of the monitoring and reporting function of the SNC online platform

AAP: This adds an additional layer to the performance indicators which includes a confidential database of contacts managed by the SNC on all service delivery points. The database is used to generate bulk SMS/key messaging, IVR and to verify service delivery. Service users interact with the platform via SMS and IVR to communicate directly on the quality of services, geographic coverage and priorities and preferences on services. It is likely that international and local NGOs will adopt and rely on the AAP platform for their activities as the system is made fully functional and accessible to all.

Experiences using AAP online to date

So far over 15,000 community contacts/phone numbers have been collected and integrated into the online platform. There are 20 or more contacts for each fixed service delivery point, as well as the headquarters of mobile sites, who can be reached to provide quality assurance and monitoring and check functionality of the services. There are 1,000 facility contacts who can be linked up with regard to specific complaints.

Although not yet launched online, complaints are already being lodged with the SNCC, with notification of issues by elders who have engaged government counterparts in the Ministry of Health (MoH) at state level. The system is operating in all states and provides an overview of quality and coverage. To date (September 2017), nine specific complaints from MoH and clan elders have been received, largely in relation to partner neutrality, clan affiliation and misuse of resources. These have been filed and addressed accordingly through a consultative verification and resolution process. Complaints that come via the MoH must be documented in a letter, which is signed and stamped by the MoH. For complaints from elders, a simple email is sufficient. Following receipt of a complaint, a bilateral meeting with the complainant is set up by the organisation.

Out of six example cases, four complaints were resolved by the partner with the community. In two cases, the organisations withdrew from the location (due to an incident related to clan affiliation and recruitment processes); one of these partners was identified as high-risk and has been denied access to resources until a detailed audit report is produced. A key guiding principle to resolving clan issues is that, as long as a partner has capacity and resources, it should be able to deliver a programme irrespective of clan.

As there is no direct communication with beneficiaries yet (this will be possible through SMS on launch of the complaints section of the online platform), no beneficiary complaints have yet been received except those organised by community elders. It is anticipated that most beneficiary complaints will concern ration size/quality, service access and service quality. Currently there is no structured template for feedback (this is in development with UNICEF). In the future, the plan is to set up a hotline which may involve a greeting, key messages and a simple structure for feedback and presenting a complaint.

The SNC is dependent to a large degree on agency self-reporting regarding the feedback received. Sub-national clusters are also informed of feedback. In addition, feedback is received via mechanisms such as United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) regular field missions. Challenges around the AAP include getting organisations to sign up to the idea and, once they have, ensuring that they share all data (currently data sharing is voluntary). Most feedback is sourced from contact points, state MoH staff and facility mangers and partners.

The online platform now maps and links technical performance indicators, such as admissions and performance, by site. This allows for greater transparency and will remedy the situation where aggregate data can mask poorer performance of individual sites. The SNC will also be able to initiate calls independently to beneficiaries around facilities/sites that are poorly performing to gain more insight and information.

On launching the platform in July 2017 a joint programme by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Health Cluster was initiated to implement health facility mapping. After 2017 the plan is to overlay health systems onto existing nutrition service data. For now, however, attention is on consolidating the approach within the Nutrition Cluster and to fully overlay or integrate access, security and food security cluster data, as well as integrated phase classification (IPC) information.

Sustaining AAP in the face of programming priorities

Despite the large-scale humanitarian assistance delivered, the Food Security and Nutrition Assessment Unit Somalia-Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FSNAU-FEWSNET) post-Gu (April to June) cereal harvest assessment (FSNAU-FEWSNET alert, 31 August 2017) indicates a deteriorating situation with sustained high risk of famine until the end of the year due to a combination of severe food insecurity, high acute malnutrition and high burden of disease. The number of people in need is estimated to be 6.2 million, including 3.1 million people in crisis. The drought is also uprooting people, with 916,000 displaced since November 2016, adding to the 1.1 million existing IDPs (UNHCR PRMN Somalia Update, 31 July 2017). This includes 130,000 newly displaced in the month of July alone. The projected number of children who are or will be acutely malnourished has increased by 50 per cent since the beginning of the year to 1.2 million, including over 231,000 who have or will suffer life-threatening severe acute malnutrition (SAM). WHO surveillance data indicates that more than 77,000 cases of acute watery diarrhoea (AWD)/cholera have been reported so far this year; five times more than the 2016 caseload. Since the start of the year, 1,115 deaths have been recorded, with a case fatality rate (CFR) of 1.4 per cent. More than 15,000 measles cases have been reported since the start of the year and an estimated 4.5 million are in urgent need of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) assistance.

Assuming the worst-case scenario, the SNC cluster is prioritising an integrated comprehensive nutrition response in drought-affected areas of Somalia. Given the current humanitarian situation and needs, the AAP is progressing more slowly due to competing demands but it remains operational and the SNC continues to document cases and lessons.

Moving forward

Since May 2017 OCHA Somalia, alongside clusters and partners, has implemented and managed a Common Feedback Project (CFP) for APP and communication with communities in Somalia for the prevention of famine. The CFP, which is based in the Drought Operations Coordination Center (DOCC) in Mogadishu and structured as an inter-agency/inter-cluster common service, is built on existing feedback mechanisms/structures and partnerships with government, clusters (including the Nutrition Cluster), local/international organisations, mobile telecoms providers and media. The CFP supports joint response planning, includes harmonised messages and aims to avoid duplication by establishing a turnkey (ready-to-use) service that every organisation can adopt and/or feed into, while allowing individual organisations and/or clusters to continue the implementation of broader AAP frameworks.

The Nutrition Cluster also engages with media and communication entities to advance AAP work. It has a framework of engagements with BBC Media Action and Radio Ergo to create an enabling environment that is independent and neutral with wider reach at grassroots level, interacting with affected populations on what matters to them (see Box 3).

Box 3: Nutrition Cluster collaboration with BBC Media Action and Radio Ergo in Somalia

BBC Media Action (www.bbc.co.uk/mediaaction) is the BBC’s international development charity. It uses the power of media and communication to help reduce poverty and support people in understanding their rights. The collaboration with the Nutrition Cluster focuses on key messaging around malnutrition and possible community actions, including where and how nutrition services could be accessed and user feedback, with the aim of informing and connecting people with cluster service providers.

Radio Ergo (www.radioergo.org/en/) is run by run by international Copenhagen-based NGO International Media Support from its Kenya regional office. The station broadcasts original humanitarian news and information in Somali every day across Somalia and the Somali-speaking region. Its aims are to amplify the voices of ordinary Somalis, enabling better communication with the wider international humanitarian community, and to provide Somali audiences with the critical information they require to make better informed choices on issues affecting their lives. The partnership with the Nutrition Cluster is being built on concrete grounds in a systematic manner. It includes informing where and how nutrition services can be accessed, messaging and interactive dialogue on what malnutrition is and what the community can do about it, and longer-term programming to empower the community on nutrition vulnerability, needs and priorities. The Cluster is working with the Radio Ergo team on an operational framework and the development of effective messaging/programming content.

Discussion and lessons learned

A key lesson learned so far is the need to ensure that AAP is mainstreamed and incorporated in the Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) cycle at a higher level, mainly through OCHA, donors and lead agencies. This will greatly facilitate and ease uptake and successful implementation of the AAP among partner agencies. Currently uptake depends on the willingness and understanding of AAP among individual agencies.

A phone-based approach was chosen because the Somali community is an oral community and mobile phone penetration is one of the highest in the region. The Nutrition Cluster is aware, however, of the importance of interpersonal skills and listening and therefore balances the use of phone/online methods with CCs and direct feedback/interactive live communications from local leaders. This ensures brokering, discussion and understanding of the different perspectives. The AAP therefore consists of more than conventional complaints and feedback mechanisms: the various feedback mechanisms have different value/acceptance in different contexts and together provide richer and deeper information.

Ideally, the SNC would have initiated the process of establishing an AAP at grassroots and/or community level with the affected population. However, difficult access, the operational reality of this context, made this impossible, limiting involvement of the community in the co-design of the AAP mechanism. Recognising this limitation, the Nutrition Cluster will explore greater involvement and feedback by the community on the mechanism itself.

Conclusions

AAP is an integrated approach that facilitates the accountability of donors and partner organisations to the affected population. It also has great potential to improve efficiency and effectiveness of the humanitarian response by creating greater transparency and a platform to facilitate full engagement of the affected population. This will create a better understanding of problems on the ground and the formulation of humanitarian actions and plans that respond to real needs and build resilience of affected communities. This will be further demonstrated over time in the Somalia context through ongoing learning and practice.

For more information, contact Samson Desie

Endnotes

1www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/651530/UK-Humanitarian-Reform-Policy.pdf

2www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/651530/UK-Humanitarian-Reform-Policy.pdf

References

Desie S. Changes to Nutrition Cluster governance and partnership to reflect learning and operational realities in Somalia. Field Exchange 52, June 2016. p68. www.ennonline.net/fex/52/nutritionclustergovernance

English

English Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch Italiano

Italiano Español

Español