Global Nutrition Cluster Rapid Response Team

By Ayadil Saparbekov

Ayadil Saparbekov has been in a position of the Deputy Global Nutrition Cluster Coordinator with UNICEF Office of Emergency Programmes in Geneva since 2013. He is a medical doctor and has a Master’s Degree in Humanitarian Assistance with focus on Nutrition in Emergencies. He has been working on management of UNICEF health and nutrition programmes since 1995, including in humanitarian contexts, in Kazakhstan, UN-administered province of Kosovo, West Darfur State of Sudan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan.

The author acknowledges the work of Action Against Hunger – UK and US, International Medical Corps – UK, Save the Children UK, World Vision Canada and UNICEF reflected in this article and the funding support of ECHO, DFID, Swiss Development Cooperation and UNICEF.

The findings, interpretations and conclusions in this article are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of UNICEF, its executive directors, or the countries that they represent and should not be attributed to them.

Location: Global

What we know: UNICEF as the Cluster Lead Agency for the Global Nutrition Cluster is committed to supporting the timely, effective and predictable coordination of nutrition in emergencies (NiE) responses.

What this article adds: In 2012, UNICEF established the GNC Rapid Response Team (RRT). to support timely coordination and information management functions through rapid deployment of nutrition cluster coordinators (NCCs) and information management officers (IMOs). The RRT is a partnership between UNICEF and AAH, IMC, Save the Children UK and World Vision Canada, managed by the GNC-Coordination Team and overseen by a steering committee. Deployment is within 72 hours (visa allowing) for up to 12 weeks. From 2012 to date, the GNC RRT has had 57 deployments to 22 high priority countries, 43% to L3 emergencies and 23% to L2. One quarter of non-deployment time was spent implementing the GNC Work Plan (including tool development) and 22% on capacity building of host agencies on the cluster approach across 20 countries. A formal evaluation in 2015 found the mechanism contributed to better coordination of the emergency response. Having established it meets a very crucial need, challenges include; lack of in-country capacity on NiE with gaps in transition contexts, retaining RRT staff and significant funding shortfalls.

Context

As part of a process of humanitarian reform, the cluster approach was introduced in 2006 by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) “to strengthen system-wide preparedness and technical capacity to respond to humanitarian emergencies by ensuring that there is predictable leadership and accountability in all the main sectors or areas of humanitarian response” (IASC, 2006). Global clusters were established, including the Global Nutrition Cluster (GNC), for which UNICEF was designated by the IASC as cluster lead agency (CLA). Despite progress following reform, the response of the humanitarian community to the Haiti earthquake and Pakistan floods in 2010 exposed ongoing weaknesses and inefficiencies in the humanitarian system. A subsequent review commissioned by the IASC Principals in 2010-2011 (IASC, 2017) exposed weakness such as lateness of the responses, inadequate leadership, lack of effective coordination structures and limited accountability for performance. In December 2011, based on these lessons learned, the IASC Principals agreed a set of actions known collectively as the Transformative Agenda, to substantively improve the humanitarian response model by working on three key areas: leadership, coordination and accountability, with focus on improved and strategic coordination (IASC, 2017).

Establishment of the GNC Rapid Response Team

In 2012, to support the Transformative Agenda and following the good example of the Global Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Cluster, UNICEF established the GNC Rapid Response Team (RRT). The purpose of the GNC RRT is to support timely coordination and information management functions in nutrition in emergencies (NiE) responses by rapidly deploying nutrition cluster coordinators (NCCs) and information management officers (IMOs). The GNC’s RRT mechanism is a partnership between the GNC and four of its partners: Action Against Hunger – UK, International Medical Corps (IMC) UK, Save the Children – UK and World Vision Canada. UNICEF, as CLA, raises funds for RRT positions that are channelled via grants to partner agencies through Programme Cooperation Agreements (PCAs). Funds cover all associated costs, including remuneration of the GNC RRT members and assignment-related costs, such as travel, per diem and accommodation. The partner agencies are responsible for the recruitment, hosting and management of RRT personnel, including facilitation of deployment related administrative issues. During their deployment RRT members are seconded to UNICEF under the terms and conditions of the Standby Agreements that UNICEF concluded with all GNC RRT partner agencies.

The GNC’s RRT mechanism started with one NCC recruited and seconded by IMC UK in 2011, initially funded by ECHO (European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations). From 2013 to date, funding for the GNC RRT has been received from ECHO, Swiss Development Cooperation and the UK Department for International Development (DFID). From 2012 to 2015, funding was provided for six GNC RRT members including three NCCs and three IMOs. Following recommendations of an evaluation of the support provided by the GNC to national coordination platforms (UNICEF, 2015), as well as funding constraints, in 2016 the number of GNC RRT members was decreased to four: two NCCs and two IMOs.

Conditions for deploying the GNC RRT

GNC RRT members are available for deployment within 72 hours of the surge request from the UNICEF Country Office for up to eight weeks with a possibility of an extension for four more weeks (total deployment up to 12 weeks). RRT members can be deployed for:

1. A declared level three (L3) emergency;

2. A rapid onset emergency or rapid deterioration of pre-existing situation;

3. The threat or forecast of L2 or L3 emergency;

4. An unpredictable and sudden loss of NCC/ IMO capacity in an established cluster/sector;

5. To strengthen underperforming NCC/IMO platforms in an established cluster/sector.

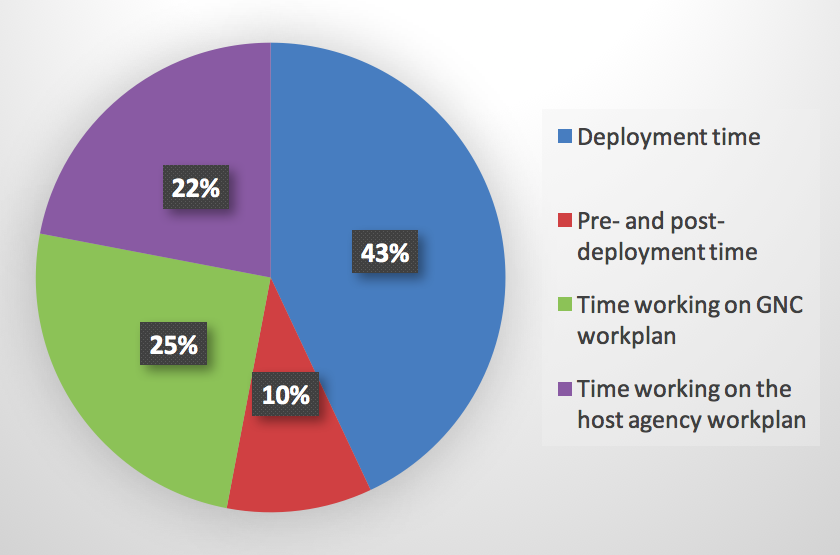

Contractual agreements are set up so that up to 50 per cent of an RRT member’s working time is spent on deployment and their non-deployment time is split equally between host agency tasks (focussing on promotion of the cluster approach within the partner agency and advancing the host agency’s NiE agenda) and supporting activities outlined in the GNC workplan. At the start of the contract or year, each RRT member develops a work plan that outlines deliverables for the non-deployment period, which is the then agreed by the host agency and consolidated at global level by the GNC Coordination Team (GNC-CT). Figure 1 below represents an average proportion of time that GNC RRT members spent on different tasks from 2012-2017.

Figure 1: Breakdown of GNC RRT support by type 2012-2017

When deployed, GNC RRT members facilitate and support nutrition cluster coordination processes at national and sub-national levels as per the IASC six core cluster functions (supporting service delivery; inform humanitarian coordinator (HC)/ humanitarian country team (HCT) strategic decision-making; plan and implement cluster strategies; monitor and evaluate performance; build national capacity in preparedness and contingency planning and support robust advocacy).

Management of the GNC Rapid Response Team

GNC RRT members are directly managed at the global level by the GNC-CT and the respective host agencies. At national level, RRT members are supported remotely by the GNC-CT and host agencies while reporting directly to a line supervisor identified by UNICEF in country. The GNC RRT Steering Committee, which consists of GNC-CT and RRT partner agencies, decides on the appropriate use of RRT members, following a request for deployment from a UNICEF country office and receipt of Terms of Reference (TOR) pre-reviewed and agreed by the GNC-CT, within 48 hours of the request being submitted. Following the Committee’s endorsement, the date for deployment is agreed with the requesting UNICEF Office, normally within 72 hours, although lengthy visa procedures can delay the departure of the RRT member in certain countries.

A monthly call takes place between RRT host agencies, the GNC-CT and all RRT members (whether on deployment or not) to manage team progress. For evaluation purposes, each RRT member submits an end of mission report after every deployment to the related country office, GNC-CT and the seconding RRT partner agency. This report details achieved results, constraints and lessons learned during the mission, as well as recommendations and follow-up actions required following their departure. Since June 2014, each RRT member has been evaluated by the UNICEF country office; results are used to tailor mentoring support for the RRT member to improve their performance. Following deployments, each RRT member is entitled to a number of days off to prevent stress accumulation and ‘burnout’ in line with the human resources (HR) regulations of their host agency.

GNC RRT deployments and activities

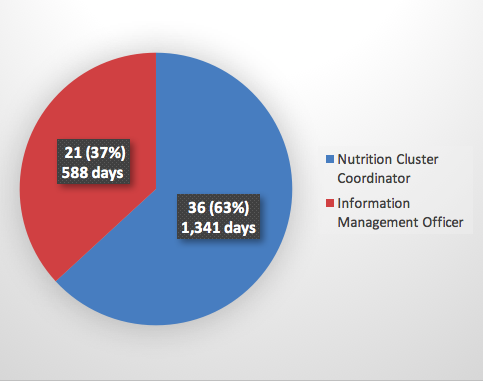

From 2012 to date, the GNC RRT members have conducted a total of 57 deployments to 22 high priority countries totalling 1,923 days with an average deployment duration of 7.3 weeks per deployment. Out of this, 24 deployments (42%) were to countries where a system-wide L-3 emergency was activated and 13 deployments (23%) were to L2 emergency countries. Figure 2 presents the breakdown of GNC RRT deployments by function from 2012-2017. Countries supported to date include Afghanistan, Bangladesh (national level and Rohingya response), Central African Republic, Chad, Ethiopia (national level and Somali region response), Haiti, Iraq, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Nepal, North-eastern Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Yemen, Ukraine, the Whole of Syria (WoS) response and Syria cross-border responses. Box 1 describes four examples of support provided by the GNC RRT in four of these countries; Box 2 provides more details of the Yemen deployment.

Figure 2: Breakdown of GNC RRT deployments by function, 2012-2017

Box 1: Examples of support provided by the GNC RRT

In South Sudan (2014), two RRT members were deployed. One of them supported the development of the Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) and Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP). This involved the analysis of existing data, review of cluster achievements and constraints to date and close working with cluster partners and the Strategic Advisory Committee (SAG) to develop the final HNO, HRP and an implementation and monitoring plan for the collective GNC partnership.

In Somalia (2013), following the sudden loss of the IMO, an RRT was deployed to support the maintenance of the Somalia information management system for eight weeks after which the Somalia country office hired a dedicated IMO.

In Sudan (2015), one RRT member and a deputy GNC Coordinator were deployed to facilitate the training of 31 cluster partners on the cluster approach. As this trip was done immediately after a cluster coordination performance monitoring (CCPM) exercise, the team helped the cluster partners and the coordinators to review the results and develop action plans to address the shortfalls in coordination.

Two RRTs were deployed to Yemen (2015), to support coordination following the declaration of an L3 emergency. This deployment took place after the HNO and HRP were already developed, so the RRTs supported implementation and programme scale-up and maintenance of coordination and information management. Given the need to restructure ways of working within the cluster, the RRT facilitated the establishment of a SAG and technical working groups (TWGs) on assessments/surveys, community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) and infant and young child feeding in emergencies (IYCF-E).

Box 2: Activities of the GNC RRT deployment to Yemen, June-August, 2015

Core functions

Achievements

- Support service delivery

Coordinated sub-national discussions on gaps/duplications and plans to scale-up; Organised a Strategic Advisory Group (SAG) to provide guidance to the cluster on strategic issues and scaling up response; Chaired weekly cluster meetings with clear agenda and action points to follow up; Initiated organisation of the Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) working group to support delivery of IYCF programmes.

2. Inform HC/HCT decision making

Organised an Assessment Working Group (AWG) to support cluster partners in nutrition surveys; Organised webinar on Rapid SMART and secured engagement of ACF-Canada in providing SMART technical support to Yemen; Led process to develop a survey plan, securing engagement of key partners; Introduced process of validation of survey protocols and reports via AWG to ensure that Nutrition Cluster had reliable data.

3. Plan and develop strategy

Operationalised the humanitarian response plan (HRP) by leading the prioritisation of districts for cluster response; Coordinated development of situation analysis and action plans for scaling up response in 14 priority governorates; Led development of the nutrition part of the inter-cluster humanitarian response plan as well as operational plan for Aden.

4. Monitor and evaluate performance

Conducted full review of information management system and developed an action plan for its improvement; Led modification of reporting tools to align with the Yemen HRP; Produced three-monthly bulletin on Nutrition Cluster response; As a part of inter-cluster efforts, contributed to production of four months response. report and weekly situation reports.

5. Capacity building of partners

Provided orientation to partners on cluster approach and their commitments to the cluster; Initiated the organising of a two-day SMART survey methodology orientation workshop to non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and identified responsible partners.

6. Advocacy

Led identification of key advocacy concerns and advocated on behalf of the cluster to partners, the Inter Cluster Coordination Group (ICCG), the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and GNC, that contributed to change in several practices, including alignment of NGOs and United Nations (UN) agencies priorities with cluster priorities; streamlining information requests to clusters and optimising inter-cluster monitoring, enhanced support of international NGO HQs to their country offices, and organising an inter-cluster supplies task force.

From 2012-2017, 25% of the non-deployment time of the GNC RRT members was spent implementing the GNC Work Plan, which included the development of the Information Management toolkit (www.nutritioncluster.net/topics/im-toolkit), consolidation of best practices on contingency planning in nutrition clusters, updating the HRP tips for nutrition clusters (www.nutritioncluster.net/resources/hrp-tips), provision of remote coordination and information management support to nutrition clusters and assistance in drafting of GNC bulletins and the updating the GNC website. Additionally, 22% of non-deployment time was used to build the capacity of host agency staff on the cluster approach and NiE, covering over 20 countries where host agencies have operational presence.

The results achieved by GNC RRT members during deployment and non-deployment times have provided clear benefits to the country cluster coordination mechanism as well as the global level host agency and GNC. Overall, countries that received surge support from the GNC RRT mechanism had coordination and information management systems up and running within a very short period of time, with collective response plans based on a clear articulation of nutrition needs, costed to provide donors and stakeholders with clear information on funding requirements to implement plans. This has greatly enabled clusters/sectors to raise funds and advocate for country-based pooled funding. The RRT mechanism also greatly contributed to the establishment of strong information systems to support effective monitoring of performance and advocacy.

The GNC-CT continues to address long term capacity gaps in coordination and information management, alongside short-term provision of surge support by the GNC RRT. The GNC-CT and UNICEF office of emergency programmes (EMOPS) senior management advocate for cluster countries to provide a dedicated cluster coordinator (or coordination person) for GNC RRT members to hand over to while still on the ground. This is now one of the conditions for deployment.

Challenges and lessons learned

A formal evaluation of the support provided by the Global Nutrition Cluster to national coordination platforms from March 2012 to September 2014 was conducted in 2015 (UNICEF). The evaluation captured both deployment and non-deployment periods of the GNC RRT members and assessed the quality of support to countries in L3 emergencies and chronic crises and the relationships with host agencies. Overall, the evaluation found that the GNC RRT mechanism contributed to better coordination of the emergency response.

The management of the RRT system by partners was found to have a positive effect on the GNC’s global credibility as the mechanism is perceived to be driven by partners with RRT members being viewed as neutral brokers. It was also noted that there was good collaboration between the GNC-CT and host agencies.

The report highlighted challenges faced by GNC partners at country level, such as the lack of capacity for NiE response, reflected in the long-term capacity gap for nutrition cluster coordination. It was recognised that this must be dealt with in a sustainable way. The report emphasised the need for handover from GNC RRT members to a dedicated coordinator in-country during the deployment period. Recruitment processes can currently be very lengthy, which must be addressed.

Another challenge highlighted by both the evaluation and through discussions with RRT members and host agencies is the difficulty in retaining RRT staff. Only one third of GNC RRT members have continued their contracts beyond the initial one-year commitment; a more sustainable funding model is needed to ensure that RRT members commit for longer. Host agencies also pointed out the difficulties of finding and hiring competent RRT members.

Funding of the GNC Rapid Response Team remains a major concern. Despite the considerable work that the GNC RRT has done over the last six years to support national coordination platforms, the mechanism is facing severe funding shortages to the extent that its existence is at risk. This is extremely unfortunate given the level of investment donors, the GNC-CT, UNICEF as the CLA, and the host agencies have made into building this essential mechanism, and given the continued capacity gap at country level which would otherwise not be filled.

Ways forward

UNICEF as the CLA for the GNC remains committed to support the timely, effective and predictable coordination of NiE responses. It is clear that the GNC RRT mechanism is relevant and effective and meets a very crucial need in countries where the cluster/sector approach has been activated, as well as in well-established nutrition cluster countries. For the next five-year programme cycle, UNICEF is integrating the positions of one NCC and one IMO into the structure of the GNC-CT. However, funding of these positions, as well as additional positions seconded by the GNC RRT host agencies, has not yet been secured. Reliable, multi-year funding provides the greatest opportunity to be able to sustain such support in order to respond to the situations where it is most needed.

For more information, contact: Ayadil Saparbekov

References

Inter-agency Standing Committee (IASC) (2006). Guidance Note on Using the Cluster Approach to Strengthen Humanitarian Response, November 2006. Available from: https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/legacy_files/Cluster%20implementation%2C%20Guidance%20Note%2C%20WG66%2C%2020061115-.pdf

Inter-agency Standing Committee (IASC) (2007). IASC transformative agenda. Available from: https://www.interagencystandingcommittee.org/iasc-transformative-agenda

UNICEF (2015). Evaluation findings of the GNC support to country Cluster Coordination platforms, UNICEF, 2015. Available from: http://nutritioncluster.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2015/06/UNICEF_report_homeprint.pdf