Strengthening nutrition humanitarian action: Supporting humanitarian cluster/sector coordination transition

By Peter Hailey and Brenda Akwanyi

Peter Hailey is founding Director of the Centre for Humanitarian Change (CHC), a humanitarian think tank based in East Africa. He has over 25 years’ experience in the nutrition and humanitarian sector in Africa, Central Asia and the Balkans.

Brenda Akwanyi is a public health nutritionist with over 15 years’ experience working with nutrition clusters and sectors in over ten countries and is currently living in Mozambique. Until December 2014, Brenda served as the Nutrition Sector Coordinator in Kenya through UNICEF embedded technical assistance in the Ministry of Health, nutrition department.

The authors extend thanks to Josephine Ippe, Global Nutrition Cluster Coordinator, and Diane Holland and Ruth Situma, UNICEF Programme Division – Nutrition, for reviewing this article. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of Tamsin Walters and Rebecca Brown of Nutrition Works as part of the team that facilitated the review report commissioned by UNICEF on which this article is based.

This article summarises the findings of a 2016 synthesis review (UNICEF and GNC, 2016) on strategic issues that UNICEF, within its Core Commitments for Children and as the Nutrition Cluster Lead Agency, should consider addressing to strengthen transition of cluster coordination structures into national coordination platforms. The article suggests approaches and a set of actions to better link nutrition coordination across the humanitarian-development nexus.

Location: Global

What we know: Through joint efforts, both nutrition emergency coordination (nutrition in emergencies) and nutrition development coordination (Scaling Up Nutrition Movement coordination) has significantly improved in the last ten years. The re-energised discussion on bridging the humanitarian and development divide should include developing approaches to link coordination of nutrition across the nexus.

What this article adds: The UNICEF and Global Nutrition Cluster Strengthening Nutrition Humanitarian Action Phase 2 synthesis review examined what is needed to operationalise transition of cluster coordination structures into national coordination platforms. As of July 2016, only 11 out of 36 (30 per cent) of activated Nutrition Clusters had transitioned1 to deactivation. Building on the Phase 1 report, the review identifies working principles to link emergency and development coordination, principles related to government leadership, a systems (rather than technical) approach, capacity development of government to lead and coordinate, capacity gaps analysis, embedding emergency coordination within sector nutrition coordination, preparedness, and phasing of support determined by changing context and competencies. An adaptive model is proposed, describing the process from cluster activation to deactivation, where government has primary responsibility to coordinate and is supported to do so wherever possible in both ‘normal’ and emergency situations. Several areas of action are identified to operationalise the proposed model, including developing and piloting a method to appraise government coordination capacity, adaptation of training approaches and tools to support government coordination competencies, and investment in emergency nutrition coordination and capacity development during nutrition emergencies. The proposed approach advocates for joint, government, humanitarian and development actors’ understanding of roles and responsibilities for nutrition coordination and is not limited to the cluster system alone.

The first World Humanitarian Summit in 2016 discussed commitments to bridge the divide between development and humanitarian partners. A call to change working modalities to respond to the rapidly changing operational landscape in which humanitarian, development and peace-building actors find themselves featured heavily. There is understanding and appreciation of the potential synergies and advantages of linking emergency and development approaches. It is recognised that emergencies put development gains at risk; consequently emergencies/disasters can no longer remain a concern for humanitarian actors only. Equally, humanitarian actors recognise that ever-increasing demands on the humanitarian system cannot be dealt with by humanitarian actors alone. In the last ten years, the three types of nutrition coordination – Interagency Standing Committee (IASC) clusters, government-led emergency or crisis sector coordination and the Scaling up Nutrition (SUN) Movement coordination mechanisms – have significantly improved. Evaluations of major emergencies had identified substantial weaknesses in coordination of responses and nutrition was very often a low priority in national development priorities. However, there is now far greater recognition of the importance of coordination for the advancement of nutrition priorities and consequently for development objectives, led by the SUN Movement. Under the SUN Movement, policy and guidance for nutrition sector coordination are being driven by the national and global SUN networks, with a focus on multi-sector coordination for nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive programming. Equally, the need for nutrition sector coordination and capacity development of government and key in-country stakeholders is recognised throughout the IASC Global Nutrition Cluster (GNC) normative policy and guidance. The SUN Movement has recognised that fragile and emergency contexts are a priority, so the suggested approaches in this article aim to guide nutrition stakeholders across the nexus to take up these opportunities for better and more linked nutrition coordination mechanisms.

Review method

The review was conducted between January and June 2016 by Nutrition Works, an international public nutrition resource group (www.nutritionworks.co.uk) on behalf of UNICEF and the GNC. It employed a combined approach of a literature review and key informant interviews (KIIs). Secondary data analysis was conducted first on the 2014 to 2015 Nutrition Cluster Transition Phase 1 study (http://nutritioncluster.net/?s=transition) to highlight the learning and good practice from country-specific analyses and review the proposed generic framework of best practice, working principles and guidance on cluster transition benchmarks produced. Secondly, relevant recent reviews covering the period 2014 to 2016 relating to humanitarian and development coordination, case studies, nutrition in emergency (NiE) toolkits and country-level resources, plus relevant UNICEF internal policy and planning documents from HQs, regional and country offices, the IASC and the GNC, were collated and analysed. To gather the views of participants on the key investments needed by UNICEF and their experiences of what has worked in relation to emergency nutrition coordination, a wide range of key informants from UNICEF management and staff (cluster and programmes), cluster partners and donors were interviewed using an in-depth, semi-structured questionnaire.

Findings

Systems approach – multi-sector, nutrition sector, nutrition emergency, nutrition cluster coordination confusion!

The review found that, in the ten years since the cluster approach began and despite very clear guidance on activating, transitioning and deactivating clusters, only 11 out of 36 (30 per cent) of activated Nutrition Clusters have transitioned to deactivation. This reflects a lack of clarity in many contexts about what coordination mechanism the Nutrition Cluster is transitioning to and how emergency nutrition coordination and cluster-led emergency nutrition coordination (NiE coordination) is positioned within nutrition sector coordination as a whole.

Consequently, the NiE coordination mechanisms are wrestling with transitioning and deactivation. The review found that policy and guidance is clear about the specific steps and issues to take into account in transitioning. The review found that in countries such as Malawi, Philippines, Kenya and Ethiopia, the nutrition sector coordination platforms and preparedness for emergency coordination mechanisms are evident and are a result of emergency coordination mechanisms providing an entry point to establish a more systemic approach to nutrition coordination. In these and several other countries the NiE coordination mechanism has often acted as the impetus or foundation on which to build longer-term sector coordination. Many countries use the cluster approach to coordinate NiE without referring to it as “cluster” (Kenya, Ethiopia, Nigeria) and the GNC provides significant support to the NiE coordination mechanisms of these countries. In these cases, a clear vision of how the whole nutrition coordination structure (emergency and development) will look significantly improved the process of transitioning from emergency to sector coordination. However, overall strategic and operational ambiguity remains in how cluster coordination capacities fit into non-cluster-led emergency nutrition coordination, as well as wider sector coordination.

The SUN Movement is focusing on government-led nutrition sector and multi-sector nutrition coordination. At present, 60 countries have signed up to the SUN Movement. The review found that while the SUN Movement has undoubtedly increased the degree of attention given to government leadership and governance of nutrition, there is still a significant challenge related to embedding NiE coordination within the wider picture of SUN government-led coordination for nutrition.

This review therefore:

- Advocates for using a nutrition coordination systems approach that bridges the emergency and development nexus, embedding NiE coordination approaches into a wider systems view of nutrition coordination as a whole.

- Suggests that a nutrition cluster envisages transitioning to deactivation and transitioning of emergency coordination to sector coordination to be the same process.

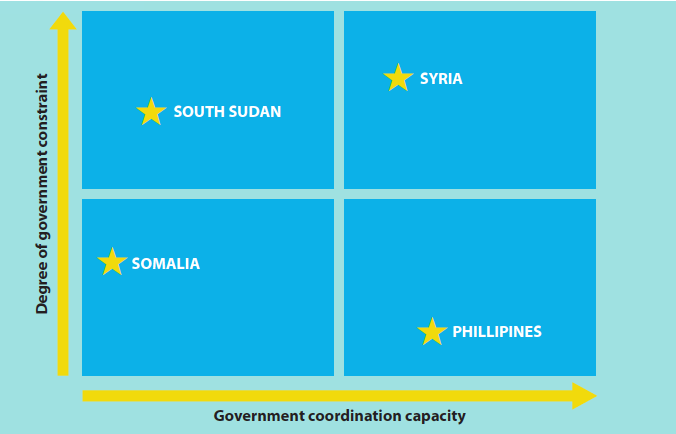

Government lead on coordination of NiE

Figure 1 shows how interviewees discussed the relationships between government constraints2 and coordination capacity to lead a response in four different country examples, from South Sudan (low government coordination capacity, high coordination constraints), to Syria (high capacity, high constraints,) Somalia (low capacity, low constraints) and Philippines (high capacity, low constraints). In these examples and in all countries considered during the review, these complexities have resulted in the development of hybrid models to manage the relationship between the cluster and the government in leading and coordinating the response. The emergence of a hybrid model for emergency coordination, response and leadership, even in places where the government’s role in leadership of the emergency response is contested, points to the need for the structure of emergency coordination and leadership in the delivery of the response to be context-specific and adaptive.

The documents reviewed from nutrition cluster and sector coordinators’ minutes and nutrition cluster/sector reports revealed different interpretations of the government’s leadership role and responsibilities, resulting in the use of different approaches to structure the emergency nutrition stakeholder’s engagement with the government. For example, in many cases government authorities act as chairs or co-chairs of cluster meetings at the national level but there is still ambivalence about how the government is put in the lead of coordination of the response. At sub-national level, there is often far less government involvement. The system-based approach to development and emergency nutrition coordination suggested by this review requires the clear understanding that the government is leading on the whole nutrition coordination system. Therefore, the proposed approach suggests that:

- On activation of a cluster or emergency coordination mechanism, it is a principle that emergency responses are government-led, except in exceptional circumstances when a government is severely constrained. In most cases, the exact nature of the relationship between the Nutrition Cluster and the government will be based on local circumstances.

|

We often confuse a state’s capacity to lead with its responsibility to lead. |

The review found examples where a government is party to a conflict or has a significant hand in causing an emergency (commission) or did not take up its responsibility to its people in case of an emergency (omission). Consequently the review acknowledges that recommendations to reinforce the role of government in leading emergency responses need to be taken in the context of a decision on the way the wider humanitarian response makes a balance between humanitarian principles and the rights and responsibilities of a sovereign state.

Figure 1: Relationships between government coordination constraints and capacity

Capacity to coordinate and activation

The decision to activate clusters is taken by the Humanitarian Coordinator (HC)/Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) or Resident Coordinator (RC) engaging in a consultative process with government. In theory, the decision to activate a cluster is partially based on an analysis of the capacity of the government to lead (and coordinate); however, the review found very little evidence of pre-emergency coordination capacity analysis or review of nutrition coordination structures, roles and responsibilities being used to inform decision making on activation of clusters. In several cases, strong government-led nutrition emergency coordination mechanisms (e.g. Nigeria and Philippines) did insist on cluster or emergency coordination mechanisms building on existing structures, but there appears to have been no structured analysis of what capacity gaps were to be filled or supported by the cluster or emergency coordination mechanism.

In other cases, somewhat subjective assessments of the government’s capacity to lead are judged against the magnitude of the need and the expected response. The lack of coordination capacity analysis means that the decision to activate a cluster is not clearly linked to building on existing government coordination capacity and its responsibility to lead. In these cases, ultimately cluster activation based on a subjective assessment of capacity to lead often results in the cluster substituting for as opposed to building on existing capacity. The review found that this lack of clarity about the difference between poor capacity to lead and the responsibility to lead makes it difficult for governments and humanitarian actors to decide when to transition and what to transition coordination to. As discussed above, a clear systems view of government-led emergency and development nutrition coordination will allow both emergency and development partners to identify what structures and capacities they will contribute to strengthening. In countries such as Pakistan, Nepal, Philippines, Ukraine, Kenya and Zimbabwe, a strong focus on the government’s responsibility to lead has resulted in a consensual process of transition and scalability of emergency coordination, as well as increasing capacity of the government to lead emergency nutrition coordination. In these and other cases, the GNC has taken a leading role in facilitating these transitions in countries with activated cluster or non-cluster emergency nutrition coordination mechanisms. The proposed approach therefore suggests that:

- Coordination capacity analysis is conducted before taking the decision to activate a nutrition cluster. If this is not possible a capacity analysis should be conducted as rapidly as possible after activation.

- The decision on when and how to transition and deactivate a cluster should be based on a capacity assessment of the government’s capacity to manage the lead and coordination of nutrition as a whole.

- Building on government capacity to coordinate and lead a nutrition response should be one of the roles of an activated cluster.

Capacity as the key metric for transitioning and deactivation

Coordination competencies (and often technical competencies for NiE) for sector, multi-sector and emergencies are not necessarily present within governments and there appears to be a low prioritisation from international nutrition organisations, including donors, to support coordination capacity development. This seems to be especially the case prior to an emergency or when the government is seen to be compromised by its role in the emergency. When capacity development of government staff does happen, the review found that international organisations, including donors, do not appear to give coordination skills of government staff the same weighting as programme core competencies (technical expertise).

Context analysis of preparedness and readiness for NiE pre-crisis in countries with the largest humanitarian needs in 2017, such as in the Middle East and countries in southern Africa, shows that these countries have very weak NiE agendas and poor awareness of the IASC cluster approach in their development nutrition programmes. In some cases, NiE preparedness actions were not explicitly featured in strategic plans due to low levels of acute malnutrition in the country. In these contexts, government, local and international nutrition partners were found to have limited competencies, skills and supporting institutional architecture to lead an emergency response. Therefore, the review found that, particularly in lower-risk/middle-income countries, preparedness for NiE and nutrition emergency coordination is not prioritised to match the rhetoric of the strategic visions of governments and international organisations concerning disaster risk reduction (DRR), government leading in emergencies, and increased resilience to emergencies of country systems. In the 36 clusters activated since 2006, most investment in strengthening nutrition coordination (emergency or sectoral) by governments, UNICEF, GNC and partners was initiated after the onset of an emergency, while many of the currently operating sector coordination mechanisms can trace their roots to an emergency nutrition coordination mechanism. In several countries, international organisation and government staff have received coordination capacity development support, mostly with a lead from the GNC and UNICEF. The review found that this training has at times taken the form of capacity development during an ongoing emergency (e.g. Syria), or in some cases in high-risk countries, preparedness for NiE (e.g the Sahel region). Yet without a systems view of how emergency nutrition coordination fits into the wider context of nutrition coordination, this somewhat ad hoc coordination capacity-strengthening process may result in less than efficient and effective impact on the overall coordination of nutrition in a country and confusion in transitioning and deactivation of clusters. The review therefore advocates for the following:

- Preparedness for emergencies, including strengthening capacity to coordinate and lead an emergency nutrition response, is a priority for regular nutrition support and for emergency and cluster (including GNC) support to governments. During an emergency, especially a protracted emergency, this support takes the form of strengthening the entire nutrition coordination system, rather than just the NiE coordination structure or cluster structure.

Funding for coordination

In recent years, significant advances have been made in adapting funding modalities to reflect and accommodate the lessons learnt in emergency programming. For example, the recent report of the High-Level Panel on Humanitarian Financing (High-Level Panel on Humanitarian Financing, 2016) and the report on the World Humanitarian Summit (United Nations, 2015), recommend use of multi-year funding and the use of the resilience approach to better link emergency-funded activities to development-funded activities. Both reports include significant commitments that require all stakeholders (implementing organisations, donors, member states and others) to change the way they work, such as making better use of different financing instruments; breaking down silos in donor budgets; increasing the localisation of responses; and increasing resilience.

A significant challenge is that emergency/humanitarian funding for coordination and for capacity development is still in siloes, as shown by the different donors’ funding arms, policies and procedures for funding coordination activities and mechanisms. Donors signalled to the review that articulation of a clear holistic model for nutrition coordination would be welcome and would help in decision making on funding coordination, particularly capacity development and preparedness for coordination3. The GNC advocacy framework has elaborated opportunities for influence between the SUN Movement and REACH (http://www.reachpartnership.org) coordination mechanisms. For instance, the GNC has articulated commitment to support SUN national multi-stakeholder platforms to analyse their nutrition plans for inclusion of emergency preparedness, response and recovery and DRR strategies and activities (Gonzalez and Mutuma, 2016).

This review therefore:

- Suggests a holistic capacity-based model for nutrition coordination and the transition between modes of coordination across cluster, emergency and sector nutrition coordination mechanisms.

Adaptive model as a way forward!

Based on the desk review (the findings from the Phase 1 report and KIIs from Phase 2), the model outlined in Figure 2 proposes a model of emergency coordination and leadership whereby government holds the primary responsibility for leading emergency response and places the foundation of nutrition sector and nutrition emergency coordination as an embedded mechanism in nutrition sector-led coordination structures. The model emphasises the need to assess governments’ capacity to coordinate, plan, activate, implement, transition and deactivate emergency nutrition coordination mechanisms, including cluster-led coordination or IASC activated coordination, and the need to optimise the government’s capacity to assume its responsibility to lead nutrition coordination in both ‘normal’ times and emergencies. Given that the vast majority of countries who might apply this model regularly experience upsurges and quiet periods in emergency nutrition needs, the model incorporates a phasing up or down aspect as part of its adaptive approach.

Box 1: Suggested working principles for emergency coordination

- Emergency responses are government-led, except in exceptional circumstances when a government is constrained.

- The value of investing in nutrition sector and emergency coordination is seen and measured using a systems-based approach to nutrition, as opposed to a technical perspective.

- Capacity development of a government to lead and coordinate a nutrition emergency response is a nutrition sector strategic priority.

- Decisions on activating, transitioning and deactivating a cluster is capacity-based using a regular capacity-gaps analysis to decide on the nature of the additional technical support required from nutrition partners.

- Emergency nutrition coordination, including cluster-led coordination, is embedded within sector coordination systems, mechanisms and processes.

- Preparedness for a nutrition emergency and nutrition emergency coordination is a strategic priority for the nutrition sector.

- External support to the government to lead and for coordination and emergency nutrition response is phased up or down based on government competencies and capacities to lead and coordinate and should not be managed as a linear process from emergency response activation through response and transition to deactivation. This is especially important in countries with recurrent or chronic emergencies.

Figure 2: Proposed emergency coordination model

Key elements of the model involve:

Nutrition sector coordination. The cycle starts and ends with nutrition sector coordination. This type of coordination is led by the government with technical assistance from UNICEF and other nutrition stakeholders.

Nutrition sector emergency coordination preparedness. The review highlights the strategic importance of preparedness as well as the emphasis that UNICEF, as cluster lead agency, the IASC and others place on promoting quality and regular preparedness planning. An essential part of this component is an emergency nutrition capacity-gaps analysis for the nutrition sector, including a focus on the government’s capacity to lead and coordinate emergency nutrition response. The gaps analysis should form the basis for the emergency nutrition capacity development plan. The analysis can also be used to set threshold-based triggers for activation of the emergency coordination response. The triggers will allow technical assistance to the government to be tailored to complement government capacity and to plan capacity development activities throughout the emergency using techniques such as mentoring and shadowing. Finally, regular monitoring of government coordination capacity, triggers and thresholds will allow the cluster and/or emergency nutrition coordination transition plans to be pre-agreed in general and amended to fit the emergency context.

Activation. Using the capacity-gaps analysis and the pre-agreed triggers described above, the nutrition sector coordination mechanism would agree to activate government-led emergency nutrition coordination. Technical assistance to the government coordination mechanism would be planned and implemented based on an analysis of the scale and severity of the emergency and how this characterisation of the emergency will affect the identified capacity gaps (See Box 1).

Emergency nutrition coordination response. The nutrition sector coordination mechanism activates the emergency nutrition coordination response based on pre-agreed triggers. This may be in the form of a technical working group for nutrition emergencies being authorised to manage and coordinate the emergency response and to regularly report to the nutrition sector coordination mechanism.

IASC cluster-led emergency response. Based on pre-agreed, capacity-based triggers and thresholds, the HC/RC and HCT, GNC and IASC, in consultation with the nutrition sector coordination mechanism led by the government, would activate the national Nutrition Cluster. The cluster would work in collaboration with the emergency nutrition coordination mechanism. The degree of collaboration would depend on the HC/RC and HCT analysis of the government constraints to lead the response using humanitarian principles. Collaboration could range from co-lead (government and UNICEF) for emergency nutrition coordination (e.g. Somalia) through to complete separation of the two mechanisms. A government would be classified as ‘constrained’ when it is unable or unwilling to coordinate (for example, because it is itself a party to conflict). It is important to note that the decision to activate the Nutrition Cluster would be based on the same pre-agreed triggers and thresholds based on an analysis of the capacity of the government to lead the coordination. Starting with this analysis will allow the cluster transition plan to be drafted at the preparedness phase and adapted to the context during the activation and response phases.

Using this model, cluster activation can happen at the same time or instead of the activation of the government-led emergency coordination. This may be the case in a very large, rapid-onset emergency where government capacity is immediately overwhelmed by the scale and severity of the emergency. Alternatively, a cluster can be activated sometime after the activation of the government emergency coordination phase. This may be the case in a slow-onset emergency where early coordination actions can be fully accomplished by the existing capacity, but thresholds are reached as the severity and/or scale of the emergency increases, dictating the need to activate the Nutrition Cluster.

IASC cluster-led emergency response + emergency nutrition coordination transition phase. As discussed above, the setting of triggers and thresholds based on a government capacity-gaps analysis allows an informed decision on activation and coordination capacity development plans before and during the emergency response. These same thresholds and capacity development plans are also used to plan and manage the transition phases of the cluster and/or the government-led emergency nutrition coordination mechanisms. The cluster can transition back to the government-led emergency coordination mechanism where an emergency resolves slowly or can transition immediately back to the nutrition sector coordination mechanism should the emergency resolve quickly.

Phase up, phase down. One common characteristic of emergency coordination and cluster-led emergency coordination, especially in chronic emergencies, is that the emergency coordination mechanisms remain activated for a long period. Yet the need for external support fluctuates significantly over the period of the crisis. This approach allows stakeholders supporting the government to tailor their technical assistance support to coordination based on emergency circumstances as they change. Regular monitoring of capacity gaps also allows thresholds for scaling up or scaling down of external coordination support to be modified to reflect changes in the government’s capacity due to on-going coordination capacity development processes. An example of a coordination competency that might be phased up or down is the support to nutrition information systems, with greater need for more and specialised capacity and resources during the peak of a shock and less during quiet periods.

Deactivation. As for activation, using a pre-agreed set of coordination, capacity-based triggers and thresholds, an informed decision to deactivate can be made by the HC/RC, HCT, IASC, GNC and nutrition sector coordination mechanism.

What it will take to adapt the proposed model

The review identifies several areas for action considered necessary to operationalise this adapted model:

- A methodology to rapidly assess a country’s (and government’s) capacity to manage and lead an emergency nutrition response should be developed and piloted in two contexts: a) as part of a process to prepare for a nutrition emergency embedded in a larger emergency preparedness process and b) in a context with ongoing Nutrition Cluster support, moving into the transition phase.

- Capacity development tools and approaches, particularly those aimed at mainstreaming emergency coordination competencies (such as training tools and learning and knowledge management strategies), should be adapted to ensure that coordination for nutrition, including emergency nutrition coordination, is appropriately included as a nutrition systems priority.

- Design a range of approaches to develop government capacity to lead and coordinate nutrition emergencies during an emergency. This should consider the likely demand on resources (including funds and human resources) for the primary life-saving objective of an emergency response.

- The Cluster Lead Agency and significant players in nutrition sector coordination should act as conveners to pilot and further develop the suggested model, thus supporting SUN and IASC structures to adapt the model and principles and agree to incorporate the model in their policies, strategies and guidance as a shared nutrition coordination model across development and emergency contexts.

- Using the agreed holistic and adaptive model for nutrition coordination, review UNICEF, SUN and IASC programme cycle and budgeting instruments to ensure adequate attention to emergency nutrition coordination and capacity development during the nutrition emergency.

- Develop and implement an advocacy strategy for senior leadership in government, local and international nutrition partners’ agencies and donors to promote the value of a nutrition systems-based approach including coordination, which incorporates nutrition coordination in emergencies, capacity building for coordination in emergencies and preparedness for emergency nutrition coordination.

For more information, contact: Peter Hailey

References

Gonzalez and Mutuma 2016. Gonzalez E and Mutuma S. Nutrition Cluster advocacy strategy framework 2016-2019: Responding to the nutritional needs of emergency affected populations. http://nutritioncluster.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/02/Nutrition-Cluster-Final-Advocacy-Framework-v2.pdf

High Level Panel on Humanitarian Financing 2016. High-level Panel on Humanitarian Financing Report to the Secretary-General: Too important to fail – addressing the humanitarian financing gap (January 2016). https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/hlp_report_too_important_to_failgcoaddressing_the_humanitarian_financing_gap.pdf

UNICEF and GNC 2016. Strengthening Nutrition Humanitarian Action Phase 2: Supporting Humanitarian Cluster/Sector Coordination Transition. A synthesis review of findings on strategic issues that UNICEF, within its Core Commitments for Children and as the Nutrition Cluster Lead Agency, needs to address in order to operationalise transition of cluster coordination structures into national coordination platforms. July 2016.

United Nations 2015. One humanity, shared responsibility: Report of the United Nations Secretary-General for the World Humanitarian Summit. http://sgreport.worldhumanitariansummit.org/

Endnote

1 Transitioning is the step between having an active Cluster and deactivating a Cluster.

2Government is classified as ‘constrained’ when it is unable or unwilling to act (for example, because it is itself party to a conflict (Cluster Coordination Reference Module 2015). A government is classified as ‘severely constrained’ when it is unable or unwilling to coordinate (for example, because it is itself a party to a conflict).

3This review was about coordination but clarity on a model for coordination to bridge the nexus will also need to to include issues of capacity strengthening for the technical aspects of NiE.