Enhancing infant and young child feeding in emergency preparedness and response in East Africa: capacity mapping in Kenya, Somalia and South Sudan

By Patrick Codjia, Marjorie Volege, Minh Tram Le, Alison Donnelly, Fatmata Fatima Sesay, Joseph Victor Senesie and Laura Kiige

Patrick Codjia is a Nutrition Specialist working for UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office, based in Kenya. Prior to this he worked for UNICEF in Malawi, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Botswana on both development and emergency nutrition programmes and in nutrition programming and research in Eastern DRC, Burkina Faso, Canada and France.

Marjorie Volege is a Nutrition Specialist with UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office. She has over ten years’ experience in emergency nutrition and development programming with UNICEF and other organisations.

Minh Tram Le is a Humanitarian Nutrition Adviser for Save the Children Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office with ten years’ experience with Save the Children and other organisations in the West Balkan region, Central and South Asia (Pakistan, Afghanistan, India) and West Africa.

Alison Donnelly is an independent Nutrition Specialist and was the Humanitarian Nutrition Advisor for Save the Children East and Southern Regional office between 2013 and 2016. Alison has over ten years’ experience in humanitarian and development programming in Africa and Asia.

Fatmata Fatima Sesay is a Nutrition Specialist for UNICEF Somalia. She has over ten years’ experience in nutrition and public health programing in both emergency and development contexts with UNICEF and other organisations.

Joseph Victor Senesie is a Nutrition Specialist with UNICEF based in Juba, South Sudan. Prior to this he worked as a Nutrition Specialist in the UNICEF Sierra Leone Country Office, with World Vision International for 12 years, and with Merlin in Liberia.

Laura Kiige is a Nutrition Specialist with UNICEF Kenya, supporting maternal infant and young child nutrition. Laura previously worked for the Ministry of Health Kenya, including as the programme manager for infant and young child nutrition.

Location: Kenya, Somalia and South Sudan

What we know: There is increasing demand to address infant and young child feeding (IYCF) needs during emergencies in Eastern and Southern Africa regions.

What this article adds: UNICEF and Save the Children Regional Offices for Eastern and Southern Africa undertook a regional capacity mapping on infant and young child feeding (IYCF) in Kenya, Somalia and South Sudan to provide a regional overview, identify capacity gaps and inform country (government and partners) action. It involved a desk review (literature, key informant interviews) and country-level workshops to validate results. An assessment tool was developed comprised of six pillars (policy, human resources, coordination, information/knowledge management, programme delivery and financing) and markers to analyse IYCF and infant and young child feeding in emergencies (IYCF-E) country capacity. Common gaps included weak policy provision and legislative frameworks for IYCF-E, significant capacity gaps (coordination, staff skillset), limited assessment/information systems that include IYCF-E, limited integration of IYCF beyond health and nutrition, and lack of funding. Country-specific findings will inform country-level IYCF-E improvement strategies and actions and the national government, national Nutrition Cluster and other partners will track progress of the implementation of action points with technical guidance from UNICEF/ Save the Children regional offices. In 2018, the capacity mapping will be extended to other countries in the region, based on previous lessons learned.

Background

The Horn of Africa continues to face challenges resulting in nutrition emergencies that greatly affect young children and their families. Key triggers are food insecurity, conflicts, disease outbreaks and climate change, among others. In these contexts, the risks of illnesses, acute malnutrition and mortality among young children are augmented; protection and support of recommended feeding practices is a critical safeguard but often falls short in practice. A review by Save the Children in 2012 found that infant and young child (IYCF) interventions were not delivered at scale during acute or protracted emergencies globally. Key bottlenecks to the scale-up of IYCF in emergencies (IYCF-E) included limited technical capacities on IYCF-E, insufficient preparedness for emergencies, lack of national coordinating bodies, funding constraints and low prioritisation. These also reflect the regional experiences of UNICEF and Save the Children in Eastern and Southern Africa, where more emphasis is placed on the treatment of severe and moderate acute malnutrition despite increasing demand for IYCF-E expertise in countries facing chronic and acute emergencies.

To address these barriers, Save the Children and UNICEF Regional Offices, under a regional framework of collaboration, agreed to focus on IYCF-E as a core priority and specifically to undertake an IYCF-E regional capacity mapping exercise. The objectives were to provide a regional overview on IYCF-E, identify key capacities, bottlenecks and gaps, and inform governments about their current IYCF-E capacity needs.

Methodology

Methodology

The capacity mapping assessment took place in two phases: phase 1 – assessment and validation and phase 2 – validation.

The assessment phase (phase 1) comprised of a desk review and interviews with key informants on IYCF-E preparedness and response, including the identification of key gaps, bottlenecks and good practices in Kenya, Somalia and South Sudan. The situations in the three countries varied and included large-scale nutrition development programmes combined with localised emergencies (Kenya) and longer-term humanitarian crises (South Sudan and Somalia). The desk review served to define relevant programmatic areas for effective IYCF-E. It appraised non-governmental organisation (NGO) programme internal and external evaluation reports and national policies, strategies and action plans relating to IYCF and IYCF-E. Key informant interviews (KIIs) targeted personnel from humanitarian organisations, government, United Nations (UN) agencies and donors. Based on the analysis, six pillars were identified to analyse the IYCF/IYCF-E capacities of a country (see Table 1). Indicators and programme markers inspired by the desk review on IYCF were selected for each pillar and a scoring system was developed to rank each country pillar and overall IYCF-E capacity. The adopted scoring system was 0 to 5 (5 being the highest) and responses were presented in a graphical manner. Each country’s score represents its performance in a particular IYCF action area. The total possible score was 145 (policy and plans=50, human resource=20; coordination=15; information system=15; programme delivery 25; budgeting and financing=20). The percentage score for each action area was calculated and scores from each action area were combined to create an overall country score.

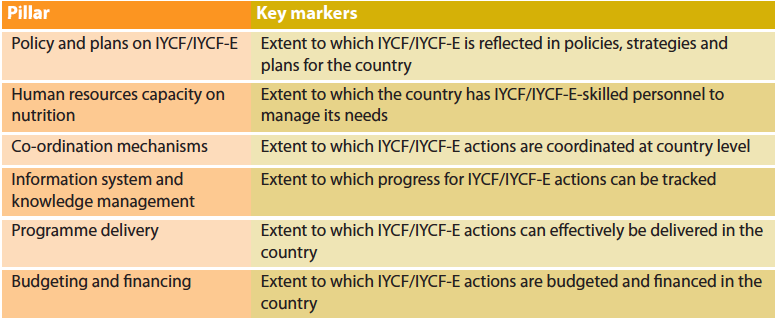

Table 1: Pillars and markers to analyse IYCF and IYCF-E country capacity

The first phase was conducted mainly in the first quarter of 2016. Assessment results of this phase were presented to the IYCF/IYCF-E counterparts from government, the UN and civil society in each country. Initial scores were reviewed and, when needed, stakeholders explained the rationale scoring. This phase was made possible thanks to the generous support of DFID to UNICEF ESARO.

The second phase involved the validation of results through stakeholder consultation in country-level workshops, supported by the Global Technical Rapid Response Team financially supported by the Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA). Final scores were validated by a wider range of stakeholders during validation workshops held within each country in 2017 (Kenya; Hargeisa and Mogadishu in Somalia; and South Sudan). Some of these final scores were revisited again by the participants. Stakeholders were based on a purposive sample, with efforts made to cover as wide a range of partners as possible. This included the IYCF Focal Points from the Ministries of Health for Kenya, South Sudan and Somalia, as well as the nutrition and health professionals overseeing IYCF programmes integrated into nutrition and health. Boxes 1 to 3 provide an overview of country findings and validated scores.

Results of the regional analysis

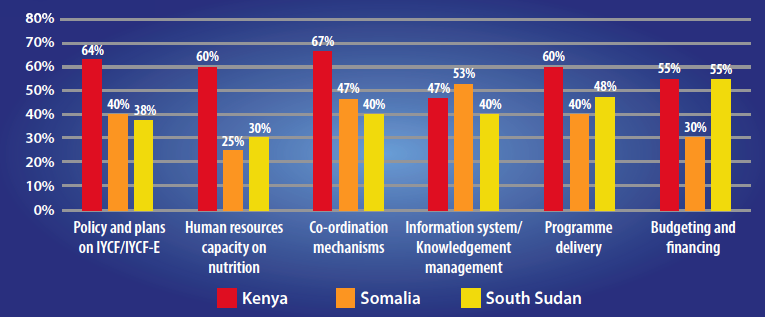

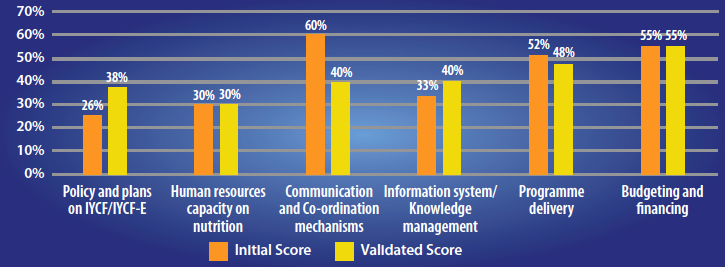

The results of the capacity mapping assessment validated by each country, displayed in Figure 1, show that all the countries had some mechanisms in place for IYCF, such as:

- Availability of national IYCF guidelines and programmes (and in some cases IYCF-E guidelines);

- A joint statement or legislation on the Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes (BMS Code)1;

- Availability of IYCF training packages, or a mechanism to conduct trainings initiated by governments or partners;

- Use of multiple communication channels for IYCF messages;

- Participation in global events like the World Breastfeeding Week;

- Availability of some form of monitoring and evaluation framework (although reporting did not always include IYCF);

- An active Nutrition Cluster or coordination mechanism.

Key findings by pillar are summarised below.

Figure 1: Validated results from overall IYCF-E capacity assessment by pillar and country

IYCF/IYCF-E policy level

IYCF policy provides the general framework for implementation of IYCF activities in ‘normal’ times, while an IYCF/IYCF-E policy incorporates implementation of IYCF in emergency contexts. Key areas assessed were:

- Availability of IYCF/IYCF-E policy/strategy/guideline developed;

- Availability of legislation on IYCF with specific consideration of emergencies;

- Recent (within last five years) guidelines to plan, implement and evaluate IYCF/IYCF-E activities;

- A contingency plan developed to promote, protect and support exclusive breastfeeding and appropriate complementary feeding and to minimise the risk of artificial feeding (with specific reference to the BMS Code); and

- Institutional roles for implementing IYCF/IYCF-E programmes are clearly defined and operationalised.

In all three countries, IYCF/IYCF-E programmes were developed as ‘national programmes’ managed by the Ministry of Health (MoH) in collaboration with UNICEF, often driven by global and regional priorities. Kenya and Somalia had IYCF strategies and policies in place (standalone or integrated); while South Sudan was using the UNICEF community IYCF package to roll out IYCF trainings nationwide (South Sudan has since developed and disseminated the country IYCF strategy). In Kenya, the full BMS Code is legislated; for Somalia and South Sudan there are no legal measures as yet2. The assessment revealed that more attention was needed to improve knowledge and dissemination of the BMS Code and reporting of Code violations by the implementing agencies in all countries.

Based on the analysis, the rating on the availability of a legal framework supporting IYCF-E was 40 per cent (20 per cent for South Sudan, 40 per cent for Somalia and 60 per cent for Kenya). In Kenya, IYCF-E is included under the 2013 operational guidelines, in addition to specific guidance for the promotion and support of infant and young child nutrition in emergencies. In Somalia and South Sudan, a specific IYCF-E section was not developed within the national IYCF national strategy and policy at the time of the first phase assessment.

Human resources capacity for IYCF-E

Adequate and supportive supervision by a staff knowledgeable on IYCF-E was missing in all countries. Essential materials for IYCF-E assessments such as standard questionnaires and orientation packages were also lacking, and staff were not adequately resourced to implement IYCF-E programmes such as counselling, community support groups and community education and care for pregnant and lactating women (PLW), especially during emergencies. Specific expertise on IYCF-E, such as on social marketing, community empowerment, advocacy and communication for development in humanitarian settings, were assessed as limited in the three countries.

Coordination and communication mechanisms on IYCF/IYCF-E

Capacities varied within the three countries, but all needed to improve national multi-sectorial coordination and collaboration across sectors and coordination between agencies at the early onset of an emergency and during needs assessment. South Sudan was the furthest along in having a multi-sectorial IYCF action plan and an IYCF-E steering committee. Somalia had several coordination mechanisms mainly through the Somalia Nutrition Cluster. In Kenya, effective IYCF and emergency nutrition coordination mechanisms were established within the MoH structure and under their leadership and support; excellent collaboration among all the partners was reported. IYCF strategies for Kenya and Somalia were developed by the government in partnerships with UN agencies and the non-governmental sector. At the time of the assessment, the South Sudan Government was developing its IYCF strategy with the support of UNICEF and the Nutrition Cluster partners.

IYCF-E information system and knowledge management

This area was rated average in all three countries. While integration of IYCF into health systems in Kenya began in 2007, there is limited reporting of maternal and infant and young child nutrition (MIYCN) national indicators in district nutrition surveillance and surveys. In Somalia, to support humanitarian nutrition information systems, the Nutrition Cluster has created an Assessment Information Management Working Group (AIMWG) to provide guidance on assessment planning, design and implementation, and validation of assessments and surveys including IYCF. In South Sudan, routine Health Monitoring Information System (HMIS) that includes IYCF indicators is largely non-operational. To address this gap, a new overall information system has been developed by the Nutrition Cluster Nutrition Information Working Group (NIWG) for emergency nutrition site-level programme data and information; this includes IYCF-E.

IYCF promotion, counselling and support programmes

This appeared to be active in all three countries assessed. Activities include revitalisation and adoption of mother and child-friendly related policies and guidelines; individual and community-level IYCF counselling, establishment of mother and baby-friendly spaces; bottle exchange programmes (where feeding bottles are exchanged for cups); and distribution of ready-to-use foods (RUFs) for children and women. Complementary feeding support involves promotion, counselling and linkage to other sectors; no robust programmes for complementary feeding were identified in any of the countries. Although all three countries had some form of existing IYCF programming in stable times, scale-up of these programmes during crisis was rare and ad hoc, mainly due to limited funding, competing priorities and limited expertise to manage this.

IYCF budgeting and financing

While there is government leadership on IYCF in Kenya and South Sudan, none of the countries had independent government financing specific for IYCF programming. The main sources of funding for IYCF and IYCF-E activities are from the UN agencies, donors and agencies’ own funding. Funding is a major constraint for all implementing IYCF-E programmes and is rarely provided for standalone IYCF-E activities. IYCF-E is not considered ‘life-saving’, so it is not prioritised or sustained for long-term activities (including preparedness). IYCF-E funding is also often cut first in case of budget constraints. While nutrition funding has increased in all three counties, funding for IYCF/IYCF-E programming has not.

Common gaps across countries

Common gaps for the three countries were:

- Lack of inclusion of IYCF-E in national policies and training curriculums: IYCF policies or strategies are in place in many of these countries, but do not encompass an emergency section, which would delay the inclusion of IYCF in any emergency response;

- Limited dissemination of national policies, legislation on the BMS Code, etc. In countries where these strategies exist, the dissemination of such documents to the humanitarian community is limited and therefore not in use or endorsed;

- Limited integration of IYCF-E with other sectors; very limited knowledge about IYCF by sectors other than Health and Nutrition;

- Inability of NGO and health workers to differentiate IYCF and IYCF-E, leading to confusion on the IYCF priorities in emergencies;

- No or limited monitoring of BMS Code violations;

- Limited budget allocation to IYCF-E programming;

- Lack of awareness of IYCF-E indicators to be included in assessments;

- No system for data collection and monitoring specifically for IYCF-E;

- IYCF-E is often not prioritised in cluster or coordination meetings.

The main reasons identified for not undertaking IYCF-E activities were:

- IYCF is not considered a life-saving intervention during emergencies and is not prioritised by non-technical staff;

- Competing priorities, poor sensitisation across agencies and lack of clear IYCF-E policy;

- Limited funding for IYCF-E programming;

- Context constraints including insecurity, poor access and lack of government leadership or guidance on IYCF-E;

- Insufficient human resources or expertise in local and international staff members and the absence of technical staff on the ground;

- Capacity gaps among partners, government facilities and field teams.

Box 1: IYCF-E capacity mapping assessment results Kenya

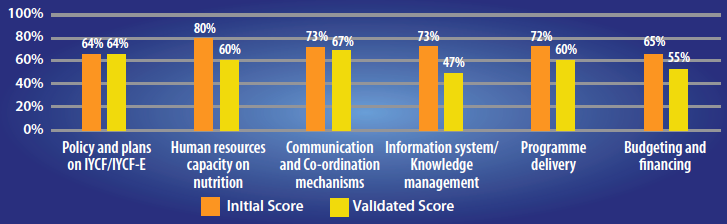

Kenya has put in place mechanisms to support IYCF-E that include having a supportive and legal framework for nutrition, enhanced coordination mechanisms, information systems and a funding mechanism for IYCF-related activities (directly or indirectly). After validation, the total score for Kenya was 60 per cent, with gaps in information and knowledge management, human resources, budgeting and financing. Overall, the participants in the validation felt the IYCF-E capacity mapping assessment results accurately reflected the situation in the country. Participant feedback indicated that some of the indicators were overrated (human resources and information systems); validated scores below reflect these changes.

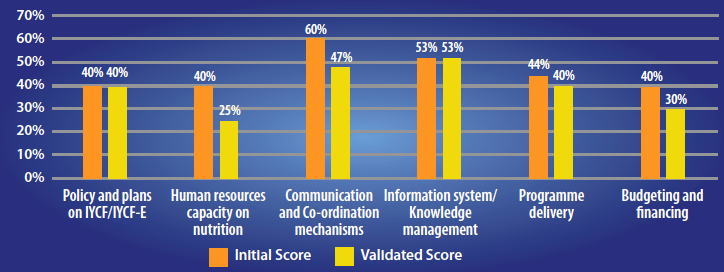

Box 2: IYCF-E capacity mapping assessment results Somalia

A strong (nutrition cluster) coordination mechanism is in place to support service delivery. While policies and systems have been strengthened, gaps remain in implementation, follow-up and engagement of all stakeholders. The total score for Somalia was 39 per cent after validation. The major constraints identified were on service delivery, relating to budget allocation and the high dependency of the country on external funding; weak IYCF-E coordination between the Nutrition Cluster and other stakeholders; inadequate implementation of policies and strategies due to government structures not being fully functional at district and community level; and limited operational capacity by government for policy implementation and enforcement.

Box 3: YCF-E capacity mapping assessment results South Sudan

Capacity for implementation of IYCF-E activities is limited in South Sudan. With support from partners, the government has put in place some mechanisms to support implementation of activities. Key to note is the development to the IYCF strategic plan which has incorporated IYCF-E. Some of the key successes in South Sudan are availability of a coordination mechanism, integration of IYCF-E in the Rapid Response Mechanism and available funding for IYCF. The total score for South Sudan was 41 per cent after validation. Health and nutrition human resources were the main barriers identified and were characterised by: lack of clear job descriptions and targets; insufficient and irregular paid compensation; lack of supportive supervision and quality control mechanisms at all levels; lack of basic information about numbers, composition and geographical distribution of health providers in the private sector; insufficient coordination of human resource development across different parts of the health system; limited continuing educational opportunities and professional development; and poor recruitment and weak retention capacity of states and counties.

Conclusions and next steps

The results of the IYCF-E capacity mapping assessment reflect a need to pinpoint IYCF actions and strategies in the East Africa region to specifically address fundamental gaps in policy, capacity, coordination, information management, programming and financing. Understanding and cohesion across development and humanitarian actors and sectors needs considerable improvement. In East and Southern Africa, UNICEF and Save the Children are important partners for IYCF-E and work closely with governments and NGOs; they are positioned as important and influential stakeholders in this area. Governments, donors, NGOs, breastfeeding associations and other stakeholders have critical roles to play in advocating for and mainstreaming IYCF-E across sectors and in emergency response and mobilising resources.

UNICEF and Save the Children Regional Offices jointly developed the IYCF-E capacity mapping assessment tool. The capacity mapping exercise demonstrated the value of gathering health and nutrition professionals to agree collaboratively on the current gaps and status of the IYCF-E implementation in a specific country and agree on a common action plan involving all key stakeholders and agencies. The next step for each country is to use the findings of the capacity mapping to develop IYCF-E improvement strategies and actions targeting the main issues and barriers identified, as well as tracking progress made. Additional technical support to countries may be required, by UNICEF, Save the Children and other nutrition agencies at national level with critical involvement from the government and national Nutrition Clusters.

The capacity-assessment process can be used in other countries in Eastern and Southern Africa region by any partner to foster the development of a specific action plan for better integration of IYCF during emergencies by governments and the humanitarian community.

UNICEF and Save the Children Regional Offices will revise the assessment tool based on learnings from the validation process and capacity mapping will be extended to other countries in the region in 2018.

For more information, contact: Patrick Codjia; Marjorie Volege; Minh Tram Le.

2Marketing of BMS: National implementation of the international code. Status Report 2016.

References

Save the Children (2012) Infant and Young Child Feeding in emergencies: Why are we not delivering at scale? A review of global gaps, challenges and way forward. Save the Children UK.