Development and added value of the Nutrition Cluster in Turkey

By Wigdan Babikir Makki Madani

Dr Wigdan Madani is the Nutrition Cluster Coordinator for Turkey, based in the UNICEF MENARO Outpost, Gaziantep. She has a PhD in Food Science and Technology from McGill University and has mainly worked for UNICEF as a nutrition specialist for the last ten years.

The author would like to acknowledge the technical contribution of the co-lead from GOAL (Lindsay Pexton, Abyan Ahmed, Aileen Wynne and Tamanna Ferdous), the Nutrition Cluster from start up to January 2017, and the co-lead from Physicians Across Continents (Mona Maman) from February 2017 to date. The author would also like to thank the Nutrition Cluster members, Syrian NGOs and international NGOs for their commitment and the great work that they are doing in scaling up curative and preventative nutrition interventions to save lives and prevent short-term and long-term consequences of malnutrition.

The findings, interpretations and conclusions in this article are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of UNICEF, its executive directors, or the countries that they represent and should not be attributed to them.

Location: Turkey

What we know: Cross-border operations from Turkey have been and remain a critical part of the Syria humanitarian response. Coordination and information sharing is complex and challenging.

What this article adds: In 2015 the Nutrition Cluster in South Turkey transitioned from a sub-group of the health sector working group to a Nutrition Cluster. Pre-cluster activation, coordination and information sharing of cross-border/crossline activities were severely hampered. Key areas of cluster action included generating nutrition information and gap analysis to inform response plans; harmonising reporting tools; developing, implementing and monitoring an infant and young child feeding in emergencies (IYCF-E) strategy and action plan that encompasses acute malnutrition treatment, micronutrient supplementation and inter-sector working; preparedness; developing capacity of national staff/local NGOs; and catalysing inter-sector collaboration. A Syrian NGO is the cluster co-lead and most partners are now local NGOs. Coordinated convoys and service delivery have been a key success of the ‘Whole of Syria’ (WoS) coordination approach. Challenges remain regarding access to besieged and hard-to-reach areas; indiscriminate distribution of breastmilk substitutes (BMS); coverage of services; and securing donor commitment in a low global acute malnutrition (GAM) prevalence context for longer-term, flexible funding that accommodates preventative as well as curative interventions.

Nutrition Cluster activation in Turkey

Prior to Nutrition Cluster activation in Turkey, there were considerable shortfalls in coordination and information sharing in programming in Syria. Nutrition occupied a small space in the health sector working group in Turkey. Donors prioritised other sectors such as food security, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and tertiary health needs in the context of low global acute malnutrition (GAM) prevalence. Less attention was given to infant and young child feeding (IYCF) problems by the donor community, who did not consider IYCF support an ‘emergency’ intervention. Inadequate information sharing between Damascus cross-line and Turkey cross-border operations led to gaps and duplication. With no official cross-border United Nations (UN) role, access to certain humanitarian funding streams (such as the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF)) was limited. A coherent and harmonised response was also severely lacking, with different guidelines and tools used by non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

Beginning in 2014, a series of UN resolutions enabled official UN cross-border activity, which paved the way for Nutrition Cluster activation in Turkey1. There was a strong push from NGOs for official recognition of cross-border operations and activation of the Nutrition Cluster. In February 2015, the Humanitarian Liaison Group (HLG) formally requested the emergency relief coordinator to activate the cluster, citing the need to coordinate partners, enable access and increase the response and cost-effectiveness of interventions in North Syria from Gaziantep, Turkey. The Nutrition Working Group (NWG) was eventually solidified in January 2015 and the Nutrition Cluster was activated one month later.

The Nutrition Cluster Coordinator (NCC) position was initially covered by short-term surge capacity from the Rapid Response Teams (RRTs), which resulted in high turnover and lack of continuity/follow-up. In the last quarter of 2015 the combined effort of the RRT NCC, UNICEF regional advisor and cluster co-lead from GOAL paved the way for the preparation of the humanitarian needs overview (HNO) and the humanitarian response plan (HRP) for 2016 and the identification of nutrition funds. A dedicated NCC was eventually appointed by UNICEF in early 2016. In January 2017, a co-lead from a national Syrian NGO was elected. The Nutrition Cluster now comprises six international NGOs (INGOs), 30 local NGOs and four UN organisations. Coordination meetings take place in Gaziantep every two weeks.

Nutrition Cluster priorities and nutrition activities

Nutrition Cluster priorities are to strengthen life-saving curative and preventative nutrition services for vulnerable population groups, focusing on appropriate IYCF practices, micronutrient interventions and optimal maternal nutrition, and systematic identification, referral and treatment of acutely malnourished cases under five years of age and pregnant and lactating women (PLWs). The Nutrition Cluster also seeks to support the development of a robust, evidence-based system through surveys and a surveillance system to inform programme implementation.

From January to June 2017 the South Turkey cross-border cluster partners reached 455,966 children under five years old and PLWs in 352 communities with both preventative and therapeutic nutrition interventions. A total of 224,729 children under five years old and 27,376 PLW were screened for malnutrition. Among them, 1,060 children were treated for severe acute malnutrition (SAM), including 48 complicated cases, and 4,170 for moderate acute malnutrition (MAM). Lipid-based nutrient supplements (LNS) were provided to 85,103 children aged 6-59 months, targeted based on food security vulnerability criteria, and counselling on appropriate IYCF was provided to 162,368 PLWs. A total of 586 health workers received training in the community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM), while 782 health workers received IYCF counselling training.

Key responsibilities of the Nutrition Cluster are to provide gap analysis of the overall response (to determine where partners are responding and identify critical gaps and areas requiring scale-up) and to accelerate/scale up the response into gap areas. Access to cross-border communities increased from 9 per cent in 2016 to 50 per cent in 2017 and access to health facilities increased from 60 per cent in the first quarter of 2017 to 70 per cent in the third quarter of 2017 (World Health Organization (WHO) health resources availability mapping system report, 2017).

The HNO and HRP were established in 2015 and include severity scores and population needs. Seventeen nutrition-specific indicators are measured, including prevalence of malnutrition (wasting, stunting, anaemia), vitamin A deficiency, nutrition programme coverage and recently added indicators from other sectors (including diarrhoea in the past two weeks, hand-washing at critical times (provided by WASH sector) and food consumption score (provided by food security sector). The HNO and HRP also identify districts that will be covered by cross-border operations and those that are covered by Damascus (cross-line) and via Amman (cross-border from Jordan). ‘Whole of Syria’ (WoS) joint planning is now a regular exercise between hubs to facilitate joint planning and avoid duplication. Nutrition surveillance was established in July 2017 (funding constraints and low GAM rates meant that surveillance was not prioritised before this) and is integrated within the Early Warning Alert and Response Network (EWARN) in 100 health facilities across seven governorates, (Aleppo, Ar-Raqqa, Dar’a, Hama, Homs, Idleb and Quneitra) to serve as an early-warning, early-action system for nutrition. Cluster partners collect data from the health facilities to contribute to the EWARN.

The Turkey Nutrition Cluster has harmonised reporting tools for the nutrition programme. In collaboration with the Health Cluster, nutrition indicators have been integrated into the health information system (using DHIS22). The DHIS2 was established in opposition-held areas (there is a de facto government that is not officially recognised by the UN), where the response is largely implemented by NGOs. The system was developed to strengthen the health system and have one reporting system instead of individual NGO systems. Nutrition Cluster interventions were also costed as part of the primary healthcare package of service developed by WHO.

Nutrition programming

Various assessments have identified low GAM, prevalent stunting and anaemia in children as significant and deteriorating problems, coupled with poor IYCF practices. Most recently, in January 2017, a SMART survey was conducted and validated in Eastern Ghouta (rural Damascus) in nine of the besieged areas and in Idleb. Prevalence of GAM was low (2.1 per cent and 2.2 per cent respectively). Prevalence of stunting was low in Idleb (13 per cent) and high in East AlGouta (30.5 per cent) compared to a national average of 16 per cent (SMART surveys, 2016). Anaemia prevalence in Idleb governorate was moderate at 35.29 per cent (578 children were tested; 204 had HGB < 11 mg/dl).

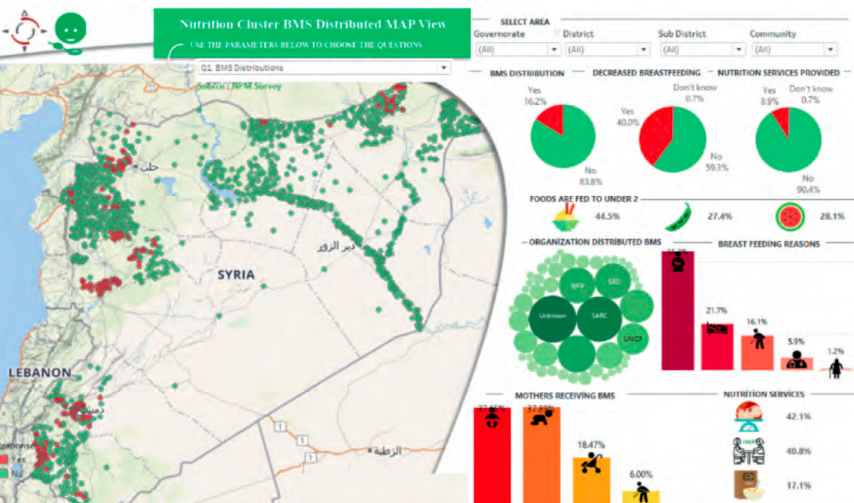

Findings from a 2014-2015 SMART survey and community surveys identified deteriorating IYCF practices within Syria, with breastfed infants using infant formula. This was linked to indiscriminate distribution of breastmilk substitutes (BMS) (16 per cent of communities had random BMS distributions, usually by Syrian NGOs operating independently of the cluster coordination mechanism; see Figure 1). Following this a scale-up of IYCF programmes by partners and large-scale advocacy and awareness-raising campaign (200 communities) by the Nutrition Cluster and partners on the standard operating procedures (SOPs) for the control of the distribution of BMS took place in 2016.

Subsequently in March 2017 the Nutrition Cluster, with technical support from the Global Nutrition Cluster RRT, conducted an IYCF knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) assessment in Aleppo, Idleb and Hama in North Syria governorates (areas accessible from Turkey cross-border). Results found low exclusive breastfeeding rates (30.9 per cent compared to 43 per cent pre-conflict), low early initiation of breastfeeding (37.8 per cent vs 46 per cent pre-conflict) and 57.3 per cent minimum acceptable diet. However, prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding had improved in Hama and Idleb from earlier post-crisis rates of 21.2 per cent and 21.1 per cent respectively (SMART, 2014-15). These findings concur with a joint community-based food security and nutrition assessment conducted in 8,088 households in seven governorates in Syria.

Some improvement in feeding practices was noted in 2017 and a reduction in reports of random distribution of BMS reflect the positive impact of the scale-up of IYCF programmes (which now covers 89 per cent of the comprehensive primary health facilities and their catchment areas) and the success of the advocacy campaign, which improved awareness of IYCF-E and BMS SOPs among NGOs in Syria. A BMS management programme now operates in IDP camps, with individual assessment of each child and guidance on BMS management. There has been some success with relactation; some mothers reestablished breastfeeding while others continued to bottle feed. Currently individual NGOs are using donated BMS supplies in accordance with the SOPs and providing BMS kits (which include a cup, water boiler and thermos to keep the water hot). The cluster has tried to secure a common pipeline for BMS supplies but this is not yet in place due to funding issues. Partners are reporting monthly on their BMS stock and consumption.

The IYCF programme also includes blanket distribution of Plumpy’Doz (a lipid-based nutrient supplement) for children aged 6-23 months for prevention of malnutrition among the most vulnerable IDPs and host community, implemented by WFP and UNICEF, and counselling on complementary feeding. The programme covers 45,000 children under two years of age, targeting only the most vulnerable IDPs and host communities based on food security criteria. Home fortification using multiple micronutrient powder (MNP) has low coverage due to poor acceptance; this is being addressed through communication and awareness-raising activities.

Nutrition programming is integrated into 75 per cent of the primary healthcare centres (including hospitals, mobile clinics and health units) in North Syria and in the primary health care package developed with WHO in 2016. Community-based IYCF programming is integrated into primary healthcare and implemented through partnerships with NGOs due to the absence of a government primary healthcare system. Informed by a capacity-gap assessment of Nutrition cluster partners in 2016, several trainings were conducted, which included cluster coordination and cluster coordination performance evaluation, facilitated by the GNC. Nine NGO partners were trained as SMART survey managers by CDC. In addition, capacity building of health staff and community health workers on IYCF counselling has been undertaken and is ongoing to support the scale-up plan in 50 per cent of communities.

Figure 1: Indiscriminate BMS distribution (2016)

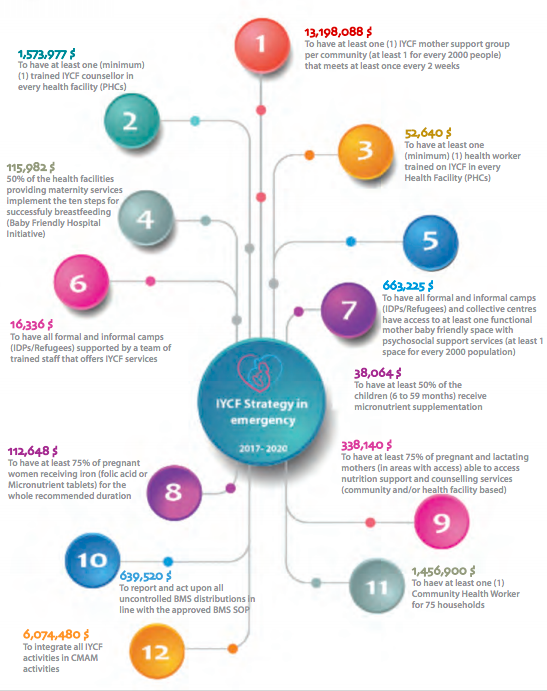

Given the context of chronic concerns and challenges in IYCF, an IYCF strategy (2017-2020) and costed action plan were developed and launched in December 2017. The overall objective is to improve the health and nutrition status of mothers, newborns and children under five years old among affected populations, using a preventative approach that also encompasses stunting and anaemia prevention. The programme targets children under five years old and PLWs and includes micronutrient supplementation and a range of integrated health, food security and WASH interventions, based on a multi-sector approach. This is backed up by health, food security and WASH cluster collaboration in North Syria. In addition, sector cluster partners launched a one-year IYCF advocacy and awareness-raising campaign in 2017 covering over 200 communities in North Syria to strengthen IYCF programming and scale up screening and treatment of acute malnutrition. This marked the beginning of a concerted effort of integration with other sectors. A recent mid-year review of the strategy revealed progress towards targets. From January-June 2017 a total 352 communities (50 per cent of 2017 target) implemented IYCF activities in 68 sub-districts (68 per cent of target). Significant progress has been made in key IYCF indicators; 162,368 PLWs (69.4 per cent of target) were counselled on IYCF and 19,430 IYCF counselling sessions (39 per cent of target) were conducted.

Figure 2: Overview of IYCF-E strategy (2017-2020)

Preparedness and IDP response

The Nutrition Cluster established five RRTs in IDP reception centres and camps and areas of expected displacements and return to support timely response to IDPs and returnees. Community health workers and mobile teams are usually deployed in immediate response. The teams supported IDPs displaced from East Aleppo, Barze, Qaboon, Alawaer, Madaya, Zabdan and Arsal. For preparedness, nutrition supplies (ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), ready-to-use supplementary food (RUSF), Plumpy’Doz, high-energy biscuits (HEB) and multiple micronutrients for PLWs and children under five years old) are pre-positioned by partners through support from UNICEF in Azaz, Jarablus, Albab and in different locations in Idleb to cover the immediate needs of newly displaced people.

In 2016 the Nutrition Cluster partners reviewed the rapid response to IDPs from Aleppo and documented overall lessons learned to improve the response to IDPs. With IYCF-E Tech RRT support (see article in this edition of Field Exchange), lessons regarding IYCF-E were used to define a minimum IYCF-E package for rapid response which takes account of limited contact time/caregiver access/opportunities for meaningful counselling. A review involving IYCF-E technical working group (TWG) members established which existing tools could be applied, which required adapting to accommodate compromises in programming, and which new tools were needed. The Tech RRT adviser also provided feedback on the overall integrated health and nutrition rapid response mechanism.

The Nutrition Cluster has worked to build the capacity of Food Security Cluster partners to integrate nutrition in the IDPs response. This has included distribution of HEB and Plumpy’Doz for children under five years of age as part of the emergency food basket and mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) screening by food security partners. Lessons learned from this experience will be documented with a view to scale-up.

Impact of ‘Whole of Syria’ approach on cross-border programming

The WoS nutrition sector has played an important role in heralding the way to share information between cross-border and Damascus-led programming; there is much closer collaboration as a result. Cross-line convoy plans to reach besieged and hard-to-reach areas are shared via OCHA and the WoS coordinator on a monthly basis. The Turkey cluster informs partners on plans and when supplies (RUTF, RUSF, Plumpy’Doz and multiple micronutrients) will arrive. Some interruptions of pipeline remain due to funding constraints.

For besieged and hard-to-reach areas, cross-line convoys deliver supplies to the local relief committees and cross-border partners are informed of the delivery; supplies may be accessed directly or beneficiaries or health staff can approach relief committees as appropriate. Additionally, cross-border partners may inform the respective hubs/sectors/clusters about the availability of and/or gaps in supplies to support the planning of future cross-line convoys. See Figure 2 for coverage from various hubs, which is currently reduced.

Integrated programming

A priority area of Nutrition Cluster advocacy is to advocate to donors on the need for integrated efforts between sectors and for more funding for the Nutrition Cluster. Advocacy to donors highlighting IYCF and related stunting issues has led to more funding through UNICEF and INGOs for capacity building of local Syrian NGOs to scale up preventative nutrition interventions and for procurement of nutrition supplies. Funding to nutrition is improving to the Nutrition Cluster and to national and international partners, but considerable shortfalls to achieve nutrition programming at scale remain. There were also delays in receiving funds in 2017 due to the diversion of funds to support famines and cholera outbreaks in other countries.

Information sharing has improved dramatically over the last two years, with stronger coordination between sectors and joint programming with both food security and child protection on nutrition. Three priority areas have been identified by the Nutrition Cluster for integration with other sectors:

- Raising awareness on IYCF;

- Blanket feeding of Plumpy’Doz (children aged 6-23 months for prevention of malnutrition) and multiple micronutrient supplementation; and

- Screening for malnutrition and referral for treatment.

The Nutrition Cluster has conducted a workshop with child protection, food security and WASH and identified areas of integration (see Box 1). It has also worked with the Food Security and Livelihoods Cluster in joint emergency response to new IDPs, integrated programming in 2017 and collaborated on nutrition-sensitive agriculture (kitchen gardening). UNICEF recently signed a project cooperation agreement with two food security partners to integrate nutrition interventions with the general food distribution and there are plans to do the same with livelihood partners. The Nutrition Cluster has undertaken capacity development on nutrition with food security, WASH and child protection partners and has developed an integrated (multi-sector) programming training manual and information, education and communication (IEC) material to support this effort.

Box 1: Integration of nutrition with child protection and WASH

Child protection nutrition activities identified at Gaziantep level include:

- Protection actors training nutrition actors at management level on safeguarding and integration within nutrition and IYCF activities.

- Integration of child protection key messages in nutrition manuals, training, and IEC materials.

- Training protection actors on nutrition activities such as MUAC screening, referral and IYCF key messages.

Nutrition activities at field level (health facilities, outreach, IYCF corners and tents, child-friendly spaces and breastfeeding counsellors include:

- Identification of a facility-level focal point on child protection.

- Trainings for those in contact with children on key child protection messages.

- Identification, reporting and referral of unaccompanied children in nutrition programmes to child protection services.

Shared strategic objectives of WASH and IYCF-E identified are:

- Reduce the risk of contamination and stop the vicious circle of waterborne diseases, diarrhoea and morbidity in infants and young children through improved access to safe water and food; improved access to quality sanitation and management of faeces; and improved food and environmental hygiene practices.

- Improve WASH in hospitals, health and nutrition centres and other institutions.

Potential integrated activities identified include prioritising caregivers of children aged 0-23 months and PLWs with potable water provision and water-related non-food items; targeted hygiene support to infants who are artificially fed; integrating questions regarding WASH and IYCF into discussions with community members; coordinating the development of IEC materials; and development of common hygiene/IYCF messaging for delivery by both sectors.

For details on integration of nutrition with food security, see WoS article in this issue of Field Exchange.

Capacity development of national NGOs

The Nutrition Cluster is co-chaired by a local NGO and national NGOs now make up a high proportion of cluster partners. The cluster has heavily invested in capacity building of national Syrian NGOs on nutrition through a series of technical trainings in IYCF, CMAM, cluster coordination, SMART surveys and rapid assessments. Previously there was limited technical capacity within national NGOs and little experience in nutrition assessment or nutrition programming. Training of trainers (TOT) has been conducted in Gaziantep for a pool of facilitators, including NGO staff who can enter Syria from Gaziantep and Syrian staff who can travel from Syria to Gaziantep (made possible through special permission from the Turkish authorities). Training is then cascaded to frontline workers with commitment to conduct post-training monitoring, coaching and mentoring. In addition, remote trainings have been conducted by Gaziantep NGOs through Skype for staff in besieged and hard-to-reach areas. Challenges have included delays in securing permission for NGO staff in Gaziantep and inside Syria to cross the Syria-Turkey borders for training and poor internet connections impacting on remote training and insecurity, making it difficult to locate staff on one training venue within Syria. However, on balance there is a great recognition and high appreciation from NGO partners of the role of the cluster in building their capacity through training, coaching, mentoring and technical support, because of the limited capacity on nutrition pre-conflict.

Remaining challenges for cross-border cluster operations

Access restrictions to some of the areas due to insecurity and other impediments continue to hamper assessment and programming. Acute nutrition needs remain that are poorly described in besieged areas; lack of information and oversight is a key constraint. For besieged areas to attract attention, they need to demonstrate acute malnutrition, which reflects a lack of awareness of the broader nutrition context and the need for stronger external advocacy. To address this, the Nutrition Cluster has joined forces with the Health Cluster; for example to highlight how the destruction of health centres impacts both health and nutrition of the population. There is more awareness that there are pockets of malnutrition within besieged areas and this is driving a more coordinated effort between hubs to ensure the delivery of supplies and establishment of services. The Nutrition Cluster has developed an advocacy strategy to complement the strategic advocacy objectives of other bodies, including the Global Nutrition Cluster as well as the Health Cluster and the NGO Forum at country level. Uncontrolled BMS distributions in Syria by national agencies continue to risk negatively impacting on IYCF practices. Managing this is constrained by low IYCF/BMS programme coverage. Funding remains low for nutrition; a priority is to secure more donor interest to support nutrition and cluster activities.

Conclusions

A more effective nutrition response in Syria requires donors to view nutrition programming as life-saving and to encompass both curative and low-cost preventative measures as a necessity. Donors and humanitarian actors traditionally only view nutrition activities as emergency response activities when conducted in contexts with high rates of GAM; this attitude must be overcome. Increased funding for nutrition programming in Syria is required that is longer-term, flexible and which allows for integration with other sectors wherever possible. An increase in resources available for cost-effective IYCF activities in particular is needed. All humanitarian actors, including local communities, NGOs, UN agencies and donors, need to commit to the Nutrition Cluster SOPs on the distribution of BMS in North Syria to ensure that any distributions are conducted in a coordinated and principled manner in line with global best-practice standards. Critically, continued advocacy is paramount for humanitarian organisations to be able to access populations in need of nutrition support with assistance that is timely, context-appropriate, coordinated, efficient and effective.

For more information, contact: Wigdan Madani

Endnotes

1UN Security Council Resolution 2165/2191/2258 authorised UN agencies and their partners to use routes across conflict lines and the border crossings at Bab al-Salam, Bab al-Hawa, Al Yarubiyah and Al-Ramtha to deliver humanitarian assistance, including medical and surgical supplies, to people in need in Syria. The government of Syria is notified in advance of each shipment and a UN monitoring mechanism has been established to oversee loading in neighbouring countries and confirm the humanitarian nature of consignments. www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/system/files/documents/files/cnv_syr_xb_regional_may_160616_en.pdf

2DHIS2 is an open-source software platform enabling governments and organisations to collect, manage and analyse data in the health domain and beyond.