Nutrition in health response in emergencies: WHO perspectives and developments

By Zita Weise Prinzo, Adelheid Onyango, Dr Ferima-Coulibaly Zerbo, Hana Bekele, Dr Ngoy Nsenga and Adelheid Marschang

Zita Weise Prinzo is the Focal Point for Nutrition in Emergencies and Undernutrition at the World Health Organization (WHO) HQ. She has worked with WHO on public health nutrition for the past 25 years.

Adelheid Onyango is Regional Adviser for Nutrition, WHO Regional Office for Africa. She has 20 years’ experience in public health nutrition research and policy issues, growth assessment and nutrition surveillance.

Dr Ferima-Coulibaly Zerbo is a paediatrician-nutritionist with extensive experience in nutrition in emergencies with WHO in the African Region.

Hana Bekele is Nutrition Advisor for the WHO/AFRO/Inter-country Support Team for East and Southern Africa countries.

Dr Ngoy Nsenga is Regional Advisor, Country Preparedness and Risk Assessment for WHO Regional Office for Africa. He has more than 20 years’ experience in management of public health and humanitarian emergencies and a particular interest in vulnerability and risk analysis.

Adelheid Marschang is Senior Emergency Officer in Emergency Management and Operations at WHO HQ, working to support protracted crises in fragile and vulnerable settings. She holds a doctoral degree in medicine and specialisations in internal medicine, tropical medicine and infectious diseases, and public health. She has more than 20 years’ experience in public health in emergencies and disaster management.

Location: Global

What we know: The World Health Organization (WHO) has an essential role in supporting Member States to prepare for, respond to and recover from emergencies with public health consequences.

What this article adds: Informed by recent experiences, WHO has reshaped its emergency programme to include creation of WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme, an updated Emergency Response Framework and adoption of the Incident Management System (IMS) to manage response. A key aim is to add a nutrition lens to WHO’s work that is beyond outbreak management. Nutrition priorities identified include development of an operations model for nutrition in emergencies for WHO and improving the availability of nutrition actions in health systems. Better contextual understanding of emergencies helps determine where WHO should be operationally involved or where indirect technical support is most appropriate. Discussions are underway within WHO on such decision making. Efforts to achieve universal health coverage include the scaling up of essential nutrition actions in line with the strategy of the Nutrition Cluster. WHO’s role as Health Cluster Lead Agency includes integration of nutrition into the health sector and close collaboration with the Nutrition Cluster/sector; development of a joint operational framework is underway. Recent WHO training in Tanzania centred on an operational model integrating nutrition and health emergency response within WHO at country level; 33 WHO staff from 14 countries participated. A training package for WHO staff will be developed for adaptation and use in other regions.

Context

Worldwide, 130 million people need humanitarian assistance and disease outbreaks are a constant global threat. Health is a top priority in all kinds of emergency, whether due to natural disasters, conflicts, disease outbreaks, food contamination, chemical or radio-nuclear spills, among other hazards. Undernutrition, in combination with a lack of access to health facilities and water supplies, leads to disease outbreaks and epidemics, including acute watery diarrhoea and cholera. During humanitarian crises, such as conflict and drought, the increased spread of communicable diseases heavily burdens the already weakened health system. In countries such as South Sudan, Somalia and Nigeria, a weak health system and low vaccination coverage can quickly trigger a vicious cycle, eventually leading to higher mortality. Studies consistently show that infectious diseases have been a major determinant of famine mortality. Malnutrition is an underlying cause in over 60 per cent of deaths, especially among children, resulting from diarrhoea, pneumonia and (in 40 per cent of cases) measles. Malnutrition among pregnant and lactating women (PLW) leads to higher-than-normal rates of mortality around childbirth.

Emergencies can undermine decades of social development and hard-earned health gains, weaken health systems and slow progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Chronic undernourishment and repeated infections contribute to high rates of stunting, while acute malnutrition (or wasting) increases the immediate risk of death two- to nine-fold among children under five years of age. Repeated episodes of acute malnutrition in childhood undermine human capital development and thus stifle the economic growth of nations. Renewed efforts to address malnutrition in emergencies are therefore imperative for saving lives, as well as ensuring long-term development.

WHO’s framework for operational emergency response

WHO has an essential role in supporting Member States to prepare for, respond to and recover from emergencies. WHO also has obligations to the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) as Health Cluster Lead Agency, to the International Health Regulations (IHR) (2005) and to other international bodies and agreements. WHO takes a comprehensive approach to all aspects of emergency management, embracing prevention/mitigation, preparedness/readiness, response and recovery. WHO supports Member States to build their capacities to manage the risks of outbreaks and emergencies with health consequences. When national capacities are exceeded, WHO assists in leading and coordinating the international health response to contain outbreaks and provide effective relief and recovery to affected populations. WHO is also a member of the Nutrition Cluster and supports the nutrition response, especially in the areas of management of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and nutrition surveillance (see Box 1).

Box 1: WHO areas of focus on nutrition in emergencies (NiE)

Life-saving programmes on nutrition and health

1) Improve capacity of health staff on the inpatient management of SAM with medical complications, including in the context of outbreaks such as cholera.

2) Improve capacity of health staff on appropriate infant and young child feeding (IYCF) (i.e. breastfeeding and complementary feeding), including risk management and support of health needs of non-breastfed infants in the inpatient management of SAM to prevent relapse.

3) Ensure necessary supplies for the inpatient treatment of SAM.

Identification of those in need of nutrition interventions and appropriate referrals

4) Integrate nutrition screening at all levels of the health system (community, primary healthcare, tertiary healthcare) including mobile clinics; ensure key nutrition interventions are conducted in the health facilities where appropriate (e.g. iron-folic acid supplementation/micronutrient supplementation in antenatal care, inpatient management of SAM) and that referral is conducted for nutrition interventions (e.g. outpatient SAM and, where needed, supplementary feeding programmes for moderate acute malnutrition and PLW).

Nutrition surveillance mechanisms and monitoring and evaluation

5) Monitor and evaluate inpatient management of SAM in health facilities, ideally integrated within existing systems. Health resources availability monitoring system (HeRAMS) to monitor availability of services and resources at different points of service delivery to identify gaps for appropriate actions, including nutrition.

6) Integrate nutrition and health surveillance. Technical support to strengthen the existing routine health information system and to integrate key programme performance indicators to monitor the outcome of nutrition services implemented at health facilities.

Fundamental rethinking and redefinition of WHO’s work in emergencies has recently reshaped its emergency programme. The second edition of WHO’s Emergency Response Framework (ERF), issued in 2017, has incorporated lessons learned from WHO’s response to recent outbreaks and emergencies, such as the Ebola response in 2016, and the reform of WHO’s emergency work. This includes the creation of WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme (WHE) in 2016 (See Box 2) and the adoption of the Incident Management System (IMS) (see Box 3 and Figure 1) as the main organisational approach to managing the response to emergencies. While the ERF focuses primarily on acute events and emergencies, it also introduces WHO’s new grading process for protracted emergencies (see Box 4). The revised ERF focuses on building the operational capacities and capabilities that enable WHO to respond more effectively to outbreaks and emergencies and on improving underlying vulnerabilities through prevention and control strategies for high-threat infectious hazards and other hazards. These strategies must be integrated with health systems strengthening, since the health system as a whole provides the foundation required to raise readiness and resilience across the board. The reform articulates better contextual understanding of emergencies, including where WHO should be operationally involved, e.g. as currently in Yemen, Central African Republic (CAR), Ethiopia (Somali Region) and South Sudan; and where to provide technical support rather than become operational. Discussions on this dichotomy are ongoing within WHO.

WHO’s responsibilities begin with early detection and risk assessment or situation analysis of a public health event or emergency. WHO supports countries to build their capacities to mitigate risks and manage outbreaks and emergencies, including nutritional emergencies with health consequences. When national capacities are exceeded, WHO assists in leading and coordinating the international health response to contain outbreaks and provide effective relief and recovery to affected populations, even if a Health Cluster has not been activated. Significant progress has been made in areas such as risk assessment and grading, and coordination of WHO’s response at headquarters, regional offices and country offices through the IMS, which provides a standardised yet flexible approach to managing WHO’s response to an emergency and the rapid release of funds from the WHO Contingency Fund for Emergencies (CFE). This rapidly disburses funds to enable the early stages of a response to humanitarian crises, disease outbreaks and natural disasters and/or to respond to rapid deterioration of crises. The fund requires constant replenishment. Since its creation in May 2015, CFE funds have supported WHO activities in more than 30 health emergency responses, including outbreaks of Ebola virus, yellow fever, cholera, Rift Valley fever and Zika virus, as well as natural disasters such as Cyclone Winston in Fiji and Cyclone Donna in Vanuatu and the climatic effects of El Niño in Papua New Guinea, and in response to complex emergencies.

Box 2: WHO Health Emergencies (WHE) Programme

The WHE has a common structure across WHO, in-country offices, regional offices and headquarters when it comes to workforce, budget, lines of accountability, processes/systems and benchmarks. It reflects WHO’s major functions and responsibilities in health emergency risk assessment and management. The Programme is made up of five technical and operational departments. Their titles and specific outcomes are:

- Infectious hazards management: Ensure strategies and capacities are established for priority high-threat infectious hazards.

- Country health emergency preparedness and the IHR (2005): Ensure country capacities are established for all hazards emergency risk management.

- Health emergency information and risk assessments: Provide timely and authoritative situation analysis, risk assessment and response monitoring for all major health threats and events, including malnutrition.

- Emergency operations: Ensure emergency-affected populations have access to an essential package of life-saving health services, including the treatment of SAM.

- Emergency core services: Ensure WHO emergency operations are rapidly and sustainably financed and staffed.

Box 3: Incident Management System (IMS)

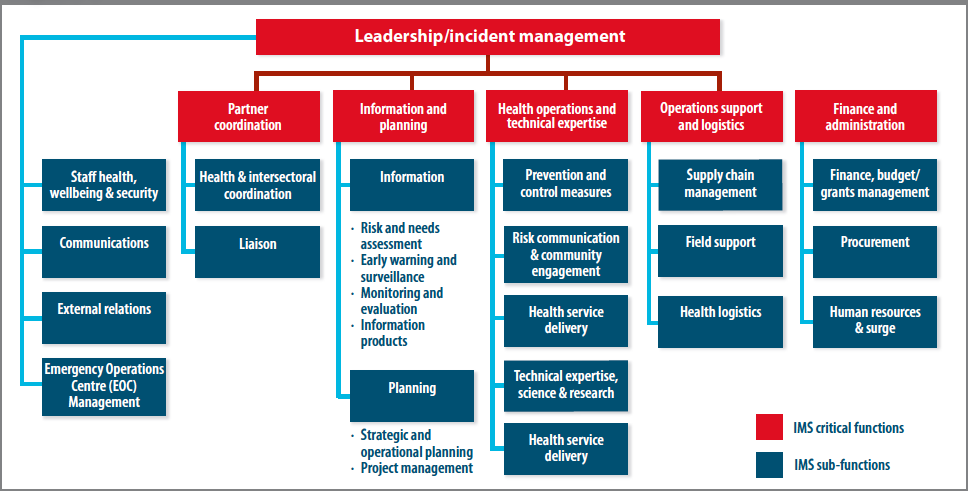

The IMS is the standardised structure and approach WHO has adopted to manage its response to public health events and emergencies and to ensure that WHO follows best practice in emergency management. WHO has adapted the IMS to consist of six critical functions: Leadership, Partner Coordination, Information and Planning, Health Operations and Technical Expertise, Operations Support and Logistics, and Finance and Administration.

On activation of the IMS within 24 hours of grading of acute emergencies, WHO will:

• Ensure the safety and security of all staff.

• Appoint an Incident Manager in-country for a minimum initial period of three months.

• Activate the emergency standard operating procedures (SOPs).

• Establish an initial Incident Management Team (IMT) in-country to cover the six critical IMS functions. This will be done initially through repurposing of country office staff.

• Establish contact with government officials, partners and other relevant stakeholders.

• Determine the need for surge support to the country to cover the critical IMS functions. This determination is made following an analysis of country office capacity to manage the emergency.

• Begin the deployment of surge support on a ‘no regrets’* basis, as needed.

• Elaborate the initial response objectives and action plan, until a more detailed plan is developed.

• Appoint an Emergency Coordinator and Incident Management Support Team (IMST) at regional or headquarters level to coordinate organisation-wide support for the response to Grade 2 and Grade 3 emergencies. A focal point will be appointed at both regional and headquarters levels for Grade 1 emergencies to coordinate any required support.

* At the onset of all emergencies, WHO ensures that predictable levels of staff and funds are made available to the country office, even if it is later realised that less is required, with full support from WHO and without blame or regret. Immediate access to funds is provided from either CFE or the Regional Office’s rapid response accounts and is replenished as funds are raised for the emergency. This ‘no-regrets’ policy applies to any expenditure incurred during the first three months of an acute emergency.

Box 4: WHO levels for graded emergencies

Grading is an internal activation procedure that triggers WHO emergency procedures and activities for the management of the response. The grading assigned to an acute emergency indicates the level of operational response required by WHO for that emergency.

Protracted emergencies (i.e. emergencies that persist for longer than six months) are assigned protracted grades to indicate the level of operational response to be sustained by WHO over a prolonged, often indefinite period.

Ungraded – Monitored by WHO but does not require an operational response.

Grade 1 – A single-country emergency requiring a limited response by WHO but which still exceeds the usual country-level cooperation that the WHO country office has with the Member State.

Grade 2 – A single country or multiple country emergency requiring moderate WHO response. Always exceeds WCO capacity and requires organisational/external support.

Grade 3 – A single country or multiple country emergency requiring major/maximum WHO response.

Figure 1: WHO Incident Management System (IMS) structure and core functions

WHO works with the local ministry of health (MoH) and partners to identify where health needs are greatest and regularly collaborates with partner networks to leverage and coordinate the expertise of partner agencies:

- Global Health Cluster: More than 700 partners are responding in 24 crisis-affected countries.

- Emergency Medical Teams: More than 60 teams from 25 countries classified by WHO to provide clinical care in the wake of emergencies, with the number expected to rise to 200 soon.

- Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN): Since 2000, approximately 2,500 health personnel have been deployed in response to more than 130 public health emergencies in 80 countries.

- Standby Partners: In 2015, WHO’s Standby Partners1 deployed 207 months of personnel support to 18 countries.

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC): WHO is an active member of IASC (the primary mechanism for inter-agency coordination relating to humanitarian assistance in response to complex and major emergencies under the leadership of the Emergency Relief Coordinator) and is a member of the Global Nutrition Cluster.

Examples of countries where WHO is operationally engaged in NiE response (SAM treatment) are Yemen, CAR, Ethiopia (Somali Region) and South Sudan.

WHO also plays a lead role in global policy guidance to inform country-level guidance development. WHO’s role includes:

- Provide effective technical support through the production and dissemination of scientifically validated and up-to-date guidelines, including interim guidelines where there are gaps in recommendations (e.g. nutritional care in Ebola response and breastfeeding in the context of Zika), norms, criteria and methodologies on:

- assessment of malnutrition, including specific micronutrient deficiencies;

- improved management of malnutrition in all its forms; and

- nutrition and health surveillance for both prevention/early warning and response.

- Strengthen, through information dissemination and training, national and sub-national capacities of the health workforce.

- Work with the government on developing and updating policies that have an impact on improving response and rehabilitation.

WHO’s role in linking nutrition and health

WHO’s Ambition and Action in Nutrition 2016-2025 is anchored on the six global targets for improving maternal, infant and young child nutrition and the global diet-related non-communicable disease (NCD) targets. In support of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, particularly SDG2 and SDG3, and with the 2016-2025 UN Decade of Action on Nutrition, WHO’s nutrition strategy aims for: “A world free from all forms of malnutrition where all people achieve health and well-being”.

One of the six WHO priorities in nutrition is to leverage the implementation of effective nutrition policies and programmes in all settings, including situations of emergency and crisis, by developing an operations model for NiE and preparedness plans to support the WHO Health Emergencies Programme. Another priority is to improve the availability of nutrition actions in health systems. Many effective nutrition actions and diagnostic procedures are delivered through health services such as provision of nutrient supplements where needed, treatment of SAM, dietary counselling, breastfeeding counselling and assessment of nutritional status. Most of these actions impact on morbidity and mortality, especially when combined with other health and poverty-reduction efforts. However, the coverage of these actions remains very low. Achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) has been established as one of the targets of the SDGs. WHO aims to ensure that efforts to achieve UHC include the scaling-up of essential nutrition actions, as reflected in WHO’s recent nutrition strategy (www.who.int/nutrition/publications/nutrition-strategy-2016to2025/en/).

The underlying causes of child malnutrition and death are not only the lack of access to food and inadequate food intake but also inadequate reproductive, maternal and child care practices and poor public health services. Necessary immediate medical interventions include the medical management of SAM and the detection and control of deadly diseases such as measles, acute respiratory infections (ARI), malaria, diarrhoea and waterborne diseases. In the mid to long-term, countries prone to undernutrition need to ensure that preventative measures are taken and that their health systems are strengthened to increase the population’s health resilience at times of famine or in settings where there is a risk of famine. In countries with high levels of food insecurity, WHO has identified several key activities to reduce the risks of missed opportunities for screening, prevention and treatment of uncomplicated illness and malnutrition and to ensure appropriate referral and synergies between nutrition and health services (see Box 5).

Box 5: Key activities to maximise service delivery in countries affected by high levels of food insecurity

Early treatment of malnutrition and illness saves lives

1. In integrated community case management (iCCM), including the ‘backpack model’ for health delivery in mobile populations, all community health workers (CHWs) should be trained to screen, treat and refer as appropriate both acute malnutrition and illness. At least malaria, diarrhoea, and ARIs should be recognised and treated by the CHWs.

2. Frequent screening for acute malnutrition and illness at community level should be used to offer a standard package of preventative care.

- All children screened should receive measles vaccination, long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLITNs), deworming and vitamin A (as per national protocol).

- All PLWs should be referred for preventative care (including tetanus vaccination, ferrous and folic acid, LLITN and malaria prophylaxis) and safe delivery as indicated.

- All outreach personnel should support coordinated social mobilisation and messaging campaigns regarding recognition of disease and malnutrition, as well as where and how to seek treatment.

Each contact with health is an opportunity to detect, refer and/or treat malnutrition

3. All people, but at least all children and PLW, presenting at inpatient and outpatient health facilities should be screened for acute malnutrition and referred to the appropriate nutrition programme or, when admitted, treated for malnutrition.

Each contact with nutrition is an opportunity to detect, refer and/or treat illness

4. All people, but at least all children and PLW, who are in nutrition programmes (including general food distribution, blanket and targeted supplementary, and outpatient therapeutic feeding programmes) should be screened for both illness and malnutrition each time there is a contact.

5. Treatment and preventative health interventions should be ensured, either integrated within the food/nutrition programme or by referral to a health facility, provided this can be ensured on the same day.

6. When referring people with either illness or malnutrition ensure

- that they actually reach the facility or programme (e.g. by supporting transport); and

- that the facility or programme has the capacity to treat all those referred on that same day.

7. All health and nutrition treatment sites should ensure the availability of the required quantities of safe drinking water and a correct water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) environment.

8. Health information and surveillance data should be shared with other sectors to ensure their inclusion in food security and nutrition analysis.

The integration of humanitarian response with a vision of recovery and long-term development is among the guiding principles of the new WHO Emergency Response Framework (WHO, 2017). This calls for comprehensive emergency response planning which seeks not only to save lives but also to address the systemic contributors to the crisis. As an example, the humanitarian crisis in the Horn of Africa has fundamental health implications for local communities. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) declared health one of four key sectors for a famine response and prevention, along with food security, nutrition and WASH.

Coordination in emergencies: Health Cluster and nutrition

WHO plays an essential role in supporting Member States to prepare for, respond to and recover from emergencies. As Health Cluster Lead Agency within the IASC, its primary responsibility is to coordinate the health response in emergencies. And since malnutrition is intimately associated with disease, WHO must strengthen the nutrition component of its emergency response strategy to achieve lasting impact. Data on food insecurity, famine and population malnutrition trends are a critical component of the information needed for early warning as well as situation analysis, risk assessment and response monitoring in major health threats and events. Similarly, nutrition interventions to prevent and treat acute malnutrition in emergency-affected populations are part of the essential package of life-saving health services expected of WHO’s emergency operations; therefore it is particularly important to integrate nutrition action in the units responsible for health emergency information and risk assessments and for emergency operations.

As Health Cluster Lead Agency, in practice WHO works to ensure a functioning coordination of the health sector, targeting vulnerable people for improved healthcare, with a focus on life-saving services including timely and adequate response to disease outbreaks and epidemics. WHO is responsible for linking the work of the Health Cluster with other clusters, including the Nutrition Cluster and the WASH Cluster. All clusters are responsible for ensuring they work effectively together, supported by OCHA.

Continued and improved information sharing and collaboration between Health and Nutrition Clusters is critical. Areas of collaboration between both clusters include joint analysis of response capacities in health facilities/centres, building capacity of health workers and partners on inpatient management, referral systems, and management of supplies for in-patient management. Both clusters must continue to examine how to better utilise the capacities of MoH staff and structures. There are instances where nutrition is a sub-cluster within the Health Cluster (e.g. Fiji, Somali Region, Ethiopia). The Health and Nutrition Clusters have initiated discussions to develop joint operational frameworks to enable better integration of health and nutrition interventions. The Global Health Cluster (GHC) Strategy outlines its commitment to strengthen inter-cluster and multi-sector collaboration to achieve better health outcomes, which involves deepening engagement with the Nutrition Cluster (see www.who.int/health-cluster/about/work/strategic-framework/GHC-strategy-2017-2019.pdf).

In close collaboration with the Nutrition Cluster and depending on the context and capacity, WHO focuses on life-saving programmes on nutrition and health, measures to improve identification of those in need of nutrition interventions and appropriate referrals, and nutrition surveillance mechanisms that generate regular information together with health (see Box 4). WHO also aims to ensure integration of nutrition into the health sector based on principles of UHC to ensure:

- Equitable access to quality life-saving services for management of acute malnutrition through systematic identification, referral and treatment of acutely malnourished cases (as reflected in Box 1).

- Access to services preventing undernutrition for vulnerable groups (children under the age of five and PLW), focusing on infant and young child feeding (IYCF) and other preventative services by:

- Scaling up IYCF interventions to protect and promote optimal IYCF practices;

- Providing essential health and nutrition services to PLW;

- Implementing a multi-programme approach where the focus is to strengthen the primary healthcare system and urgently attend to SAM children with severe complications.

WHO aims to use every contact, for example during immunisation and health checks, to incorporate nutrition activities, such as nutrition screening and appropriate referrals.

Building WHO country-level capacity to integrate nutrition into health response in emergencies

WHO needs a solid base of internal capacity close to where emergencies happen to deliver on commitments. A flagship effort in this regard involved a recent pilot training in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (29-31 August 2017) on an operational model integrating nutrition and health emergency response. Thirty-three WHO emergency and nutrition officers participated from 14 countries in crisis or at risk thereof; namely Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, South Sudan, Uganda, Tanzania, Nigeria, Niger, Chad, Cameroun, CAR, Burundi, Mali and the Democratic Republic of Congo. This was the first time WHO has conducted a training of this kind and was welcomed by participants, who acknowledged the strong link between the two areas of WHO’s work.

The aim of the training was to enable WHO country staff to work effectively and safely in emergencies as part of surge teams to implement WHO activities as outlined in the ERF. This capacity building is part of the transformation to strengthen WHO’s management of health crises and to enhance knowledge and practice on NiE settings. The nutrition and emergency focal points are based in WHO country offices. The nutrition focal points often ‘double hat’ for child health and non-communicable diseases (NCDs), which can be challenging when it comes to their involvement in responding to emergencies. However, this also offers opportunities to support government in preparedness, programme continuity and developing linkages between humanitarian and development efforts.

The overall objective of the workshop was to orient WHO staff on WHO emergency operations and malnutrition management in emergencies, with the goal of integrating nutrition actions in the response to health emergencies. The training was conducted by facilitators from WHO with support from external training experts. A range of topics included an overview of WHO ERF and its role in the humanitarian architecture and coordination; collaboration with other humanitarian agencies in situation analysis for needs assessment and defining nutrition priorities; strategic response planning and implementation; evaluation and results tracking; and resource mobilisation. To assess learning, a case study of a country in emergency served as a framework running through the different stages of emergency response planning. Country-specific plans were developed by each of the participants on how to apply what they learned to their own contexts.

With specific reference to nutrition, the training went into greater depth on its relevance in the preparedness, response and rehabilitation phases of emergencies; overview of malnutrition and its immediate and underlying causes and indicators; nutrition assessments and classifications; surveillance and surveys; classification of the nutrition situation; population-level indicators and cut-offs; and the utility of the integrated phase classification (IPC) for food security and nutrition as a tool to identify the degree of public health importance of the nutrition situation in the emergency, given aggravating circumstances and underlying vulnerabilities.

The session on nutrition interventions included how to manage SAM in isolation and in the context of infectious diseases such as cholera, other diarrhoeal diseases, measles and malaria, which commonly occur in emergencies. The session on planning highlighted the necessity of assessing the scale of the disaster, risks and response needs considering underlying vulnerabilities and antecedents to the event. Nutrition was integrated into relevant actions in line with the WHO health system building blocks for planning, long-term recovery and rehabilitation. Channels for resource mobilisation were considered. This workshop was a first step in integrating nutrition and health in emergencies at country level; a WHO consultant will follow up with participants on what needs to improve and how.

Next steps will involve consolidating and refining the training content that was drawn from various training packages, including the IASC Nutrition Cluster Harmonised Training Package (HTP) and developing a training package for WHO staff for adaptation and use in other regions.

Conclusions

The WHO reform has strengthened WHO’s capacities for all hazards emergency response by drawing on required technical expertise from different health areas and support services, and offers opportunities to strengthen nutrition in health response. WHO is traditionally well placed to combine immediate emergency health response approaches with longer-term actions to address underlying issues and causes and sustainable interventions in emergency risk management. The main challenge is how to sensitise and get WHO staff of non-nutrition programmes fully on board with nutrition concerns, so that any opportunity to capitalise on WHO’s comparative advantages in the health sector is not missed. Attention is centred on SAM management and surveillance in countries; there is a need to further integrate other emergency nutrition activities, such as nutrition-sensitive interventions.

For more information, contact: Zita Weise Prinzo

References

WHO (2017) WHO Emergency response framework – 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/258604/1/9789241512299-eng.pdf

Endnotes

1Standby Partners are organisations with strong networks of deployable technical professionals. WHO’s Standby Partnerships are managed by WHO HQ. WHO signs a global Standby Partnership agreement directly with the Standby Partner organisation which has a contractual relationship with the individuals who serve as Standby Personnel, e.g. CANADEM, DEMA, Norwegian Refugee Council.