Experiences of Nutrition Sector coordination in Syria

By Muhiadin Abdulahi

Muhiadin Abdulahi has worked with UNICEF Syria as a Nutrition Sector/Cluster Coordinator since July 2015, before which he worked as a nutrition specialist for UNICEF Syria from March to June 2015. He has over 13 years’ experience working in nutrition in emergencies, household economy approach, nutrition assessments and food security in Ethiopia, Sudan, Kenya, South Sudan, Somalia and Syria.

The findings, interpretations and conclusions in this article are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of UNICEF, its executive directors, or the countries that they represent and should not be attributed to them.

Location: Syria

What we know: A coordination mechanism for emergency nutrition did not exist in Syria pre-crisis as the country was among low-middle income countries with less need for emergency response. Nutrition programming comprised prevention and surveillance, with no capacity to treat acute malnutrition.

What this article adds: A Nutrition Sector coordination mechanism was initiated in 2013 in Syria. Scope and participation was initially limited but has evolved into a strong government-UNICEF co-led initiative, with high national partner participation. There has been considerable investment in capacity building of national partners, international partners, United Nations (UN) agencies and Ministry of Health. Access to funding by national agencies has increased. Needs assessments have informed nutrition response plans across the country. Cross-line and cross-border programme coordination has been greatly facilitated by the development of the ‘Whole of Syria’ (WoS) approach that includes a common Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP). Access to those affected has improved through negotiated, inter-agency, cross-line convoys that are cooperatively planned with cross-border operations, reducing duplication and maximising synergies. Challenges remain in meeting needs in UN declared besieged and hard-to-reach areas, supporting internally displaced persons (IDPs) and regarding national non-governmental organisation (NGO) operational and technical capacity to deliver at scale.

Background

Syria, once a lower-middle income country, had little experience of emergency nutrition prior to the current crisis as there was no need for emergency response. The focus of the Ministry of Health (MoH) primary healthcare services with regard to nutrition was the promotion of preventative behaviours and nutrition surveillance; no treatment of acute malnutrition through community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) existed due to the low acute malnutrition caseload in the country. Furthermore, as health services delivery was well covered by the MoH, there was no need for non-governmental organisation (NGO) partners and therefore no nutrition coordination mechanism was required.

Due to the Syrian conflict the delivery of basic health services was severely disrupted and a need emerged for support from the humanitarian community. In view of this, after major advocacy by UNICEF and other United Nations (UN) partners, the Nutrition Sector was established in March 2013. Initially, scope and participation were limited as few partners existed and nutrition was not yet seen as a priority by the government with the perception that no malnutrition related problems existed. Many challenges were faced from the outset as the concept of coordination was not well understood and engagement and participation of national NGO partners in coordination fora was not welcomed by government. However, over time, there has been considerable progress. This article describes the process of establishing Nutrition Sector coordination in Syria and challenges and lessons learned.

Emergence of Nutrition Sector coordination in Syria

The Nutrition Sector began with few partners, mainly UN agencies (UNICEF, the World Food Experiences of Nutrition Sector coordination in Syria By Muhiadin Abdulahi Programme (WFP) and the World Health Organization (WHO), MoH and the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC). Government authorities were initially sceptical of the valid role of national NGO partners in the emergency response and were therefore reluctant to include them in coordination activities. During this difficult period, the cluster lead agency (UNICEF), through the Nutrition Sector, supported national partners to continue their response while at the same time advocating to the authorities for their inclusion in coordination fora at all levels. Because of this continued advocacy, and with the recruitment of a designated sector coordinator, the participation of national NGOs increased gradually from five in 2013 to 60 in 2017.

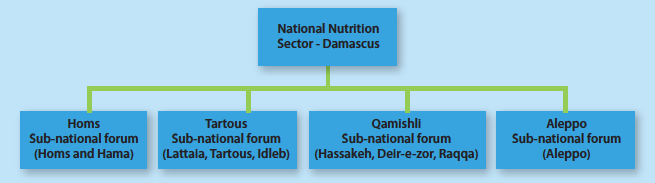

The Nutrition Sector is co-led by the MoH and UNICEF. There are also four sub-national coordination fora, in Aleppo, Homs, Tartous and Qamishli. As indicated in Figure 1, each sub-national forum covers several governorates which are supported by the UN hub. In addition, the sector has a technical working group (TWG) which provides support on matters pertaining to the response strategy, protocols and guidelines. Due to the evolution of the role of national partners, they are now part and parcel of the system and their key role in the emergency nutrition response is acknowledged. National partners form part of the sector TWG, along with MoH, UN agencies and international NGOs, and are involved in technical thematic areas such as development of infant and young child feeding (IYCF) strategy, community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) protocols, and training packages, surveillances system and reporting tools.

The sector prioritised development of technical and coordination capacity of sub-national focal points from Directorates of Health (DoH) and UNICEF, the central nutrition team at MoH as well as sector partners. This involved trainings in-country and outside the country facilitated by the sector supported by the WoS nutrition sector and the Global Nutrition Cluster (GNC). Adequate nutrition coordination capacity was created among the sub-national focal points from UNICEF and Ministry to lead the response.

Figure 1: Nutrition Sector structure and geographical coverage in Syria

Initially, the Nutrition Sector focused on capacity development of partners, particularly MoH, including the introduction of the concept of nutrition in emergencies (NiE) and the implementation of small-scale, preventative nutrition activities, such as the provision of high-energy biscuits (HEBs), fortified spread, micronutrients; limited promotion and counselling sessions through MoH health facilities; and partner-run programmes and curative nutrition services. The sector has since expanded efforts to engage the food security and agriculture sectors in the development of common tools for assessments and key messaging around optimal feeding and proper use of nutrition products, as well as delivering nutrition interventions through food security mechanisms. With support from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the Nutrition Sector has initiated small-scale, nutrition-sensitive activities through schools and at household level. The initiative provides nutrition information and agricultural inputs to school children and their teachers and families to establish backyard gardens at school and home to improve access to nutritious foods.

Achievements

The Syria Nutrition Sector has made significant progress since it was established in 2013. Achievements include the integration of nutrition services such as mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) screening into polio and measles campaigns; nutrition surveillance in MoH health centres; provision of lipid-based nutrition supplements (LNS) through food security platforms; development of curative services in MoH health centres; and cross-line convoys as part of the Whole of Syria (WoS) coordination effort.

Efforts have also been made to develop standards and protocols for the delivery of both preventative nutrition services (IYCF, provision of fortified foods, micronutrients and HEBs) and curative nutrition services (identification and treatment of acute malnutrition). The TWG has developed a CMAM protocol in the form of field cards translated into Arabic for easy use by services providers, CMAM and IYCF training packages and tools, and standardised reporting templates, such as the 4W matrix to collect information on who is doing what, where and when to monitor the response and identify gaps. These tools were further harmonised and shared across hubs.

In addition in 2015-2016 the Nutrition Sector, through the MoH and with the financial and technical support of UNICEF and technical support of Medair and WFP, conducted SMART nutrition surveys in accessible areas, including 11 of the 14 governorates in Syria (the exceptions were Deir-e-zor, Ar Raqqa and Idleb). The SMART surveys identified an acceptable level of global acute malnutrition (GAM) of three per cent and 0.6 per cent severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in children, moderate levels of acute malnutrition among women (7.8 per cent), moderate public health problem levels of anaemia among both women and children, and poor IYCF practices. These findings were used to inform the 2017 Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO)/HRP and guided nutrition responses in 2017 and subsequent plans. Subsequently, the sector prioritised promotion and support for optimal IYCF practices, provision of micronutrients and other fortified supplements, and strengthening of the identification and treatment of acute malnutrition in pocket areas, as well as integration with other sectors.

The Nutrition Sector supported 550,000 and 260,000 women and children in UN declared besieged and hard-to-reach areas in 2016 and 2017 respectively through the provision of essential, life-saving nutrition supplies delivered in inter-agency, cross-line convoys. The convoys included nutrition supplies such as LNS (Plumpy’Doz), multiple micronutrient powders (MNPs) for children; micronutrient tablets for mothers; HEBs for prevention of undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies; and therapeutic and supplementary supplies such as Plumpy’Nut, therapeutic milks and supplementary foods for the treatment of SAM and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM). These supplies were accompanied with a simplified CMAM protocol and flyers to raise awareness on the use of preventative nutrition supplies. In addition, the Nutrition Sector made efforts to create capacity through remote technical support in close collaboration with other hubs, although this was very challenging as carried out through skype calls.

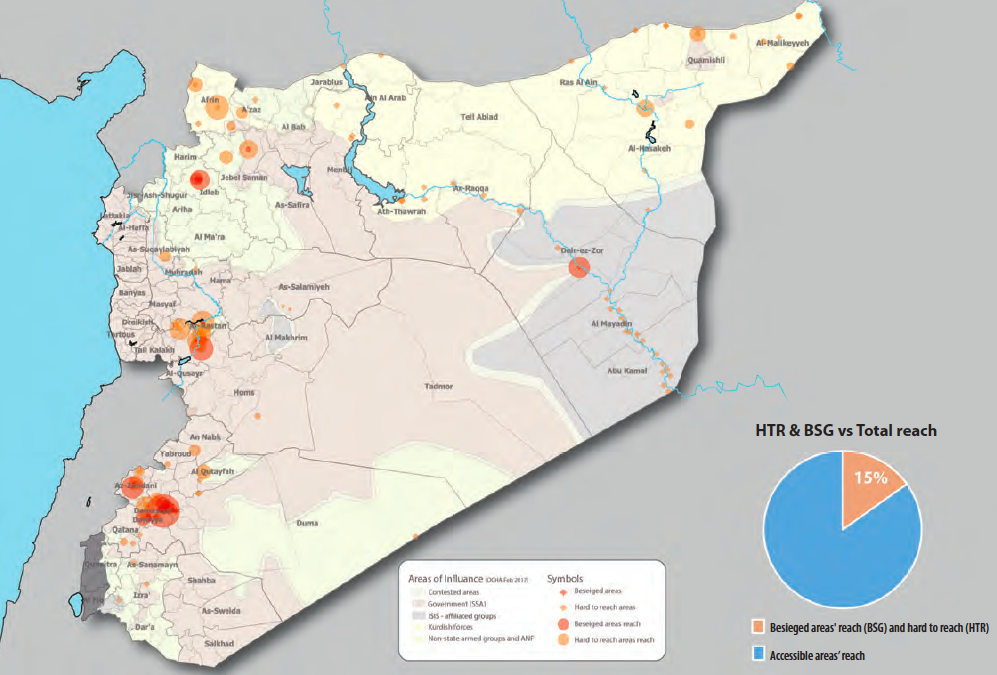

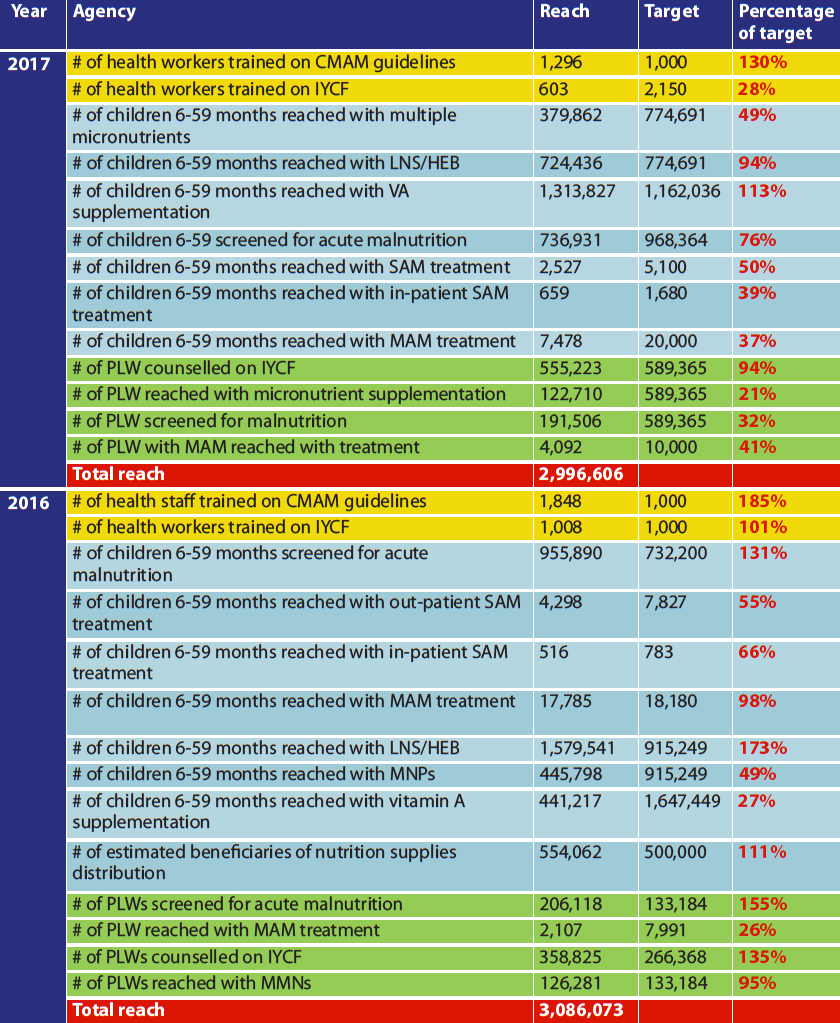

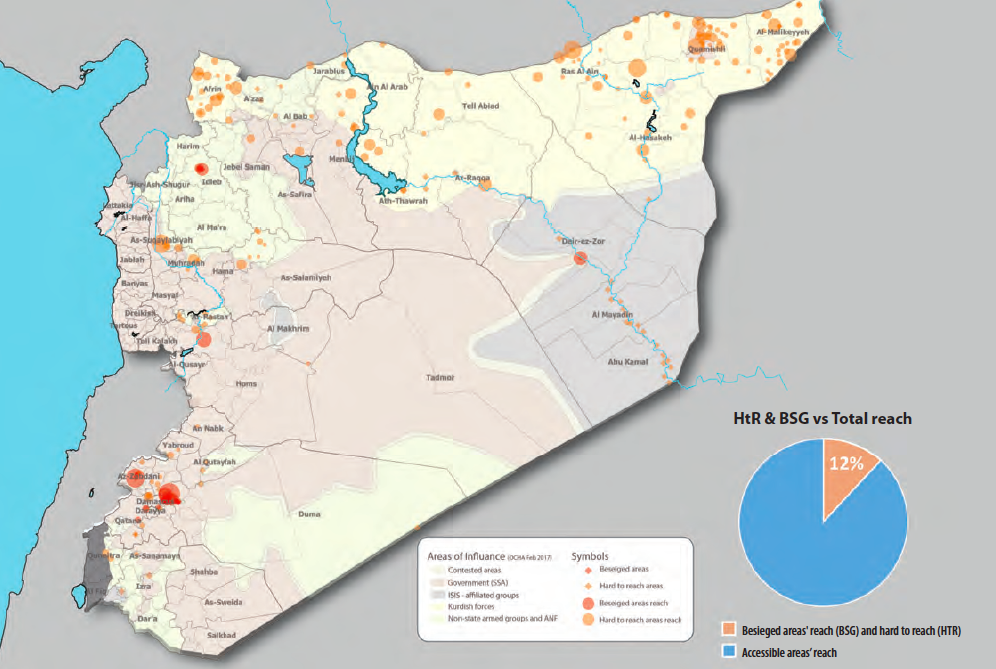

Table 1 summarises the Nutrition Sector’s reach in 2016 and the first half of 2017. As indicated in the table, the sector delivered life-saving nutrition services in accessible areas in 11 out of 14 governorates throughout the country, as well as UN declared besieged and hard-to-reach areas. Several indicators were constrained, including provision of multi-micronutrients and treatment of acute malnutrition among pregnant and lactating women (PLWs) and children, largely due to lack of access, capacity, funding and operational challenges, including the fact that PLWs are served by the reproductive health department rather than the nutrition department in the MoH. However, most other indicators performed well. The total reach of the Nutrition Sector in 2016-2017 was mainly in accessible areas of the 11 governorates (78 per cent of total reach) rather than in UN declared besieged and hard-to-reach areas (22 per cent). Figures 2 and 3 show the geographic spread of reach.

Table 1: Nutrition Sector reach (number of women and children provided services) in 2016 and 2017

Figure 2: Syria Nutrition Sector reach in besieged and hard-to-reach areas through convoys in 2016

Figure 3: Syria Nutrition Sector reach in besieged and hard-to-reach areas through convoys, Jan to August 2017

Added value of the ‘Whole of Syria’ (WoS) approach

UN Security Council Resolutions 2165 and 2191 in 2014 paved the way for the provision of humanitarian assistance to people in UN declared besieged and hard-to-reach areas through inter-agency, cross-line convoys (from Syria) and cross-border convoys (from Turkey). In line with these resolutions, the humanitarian community in Syria, under the lead of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and with the close coordination of SARC, initiated the inter-agency delivery of supplies to people under the WoS approach. This process is described elsewhere (see article on the WoS approach in this edition of Field Exchange).

Prior to the establishment of the WoS architecture, the Nutrition Sector faced challenges in planning and delivering nutrition interventions in UN declared besieged and hard-to-reach areas. The main challenges faced included a lack of information sharing between hubs in Syria, Turkey and Jordan, which led to programme gaps and duplication in certain areas; varied and limited access by different hubs to the affected population; inadequate nutrition capacity in the UN declared besieged and hard-to-reach areas affected by the lack of access; lack of trust between hubs (making cooperation difficult); and the application of different standards in different areas/hubs due to difficulties in sharing programme information, guidelines and protocols.

However, with the inception of the WoS structure, these challenges were gradually overcome as trust between hubs was built and cooperation improved. For example, the sub-national focal points with their counterparts in the Directorate of Health (DoH) in Aleppo and Hassakeh responded to internally displaced persons (IDPs) from Ar Raqqa and Aleppo during the escalation of the conflict at the end of 2016. The response was made more effective by improved levels of engagement with the WoS team, which played a key role in improving information sharing, creating a conducive environment for hubs to work together, and by providing a platform for experience sharing and mobilisation of cross-border partners.

To facilitate access to UN declared besieged and hard-to-reach areas, OCHA set up an Access Working Group (AWG) attended by sector/cluster coordinators, cluster lead agencies, key UN agency members, OCHA and SARC. The AWG meets in the middle of every month to prepare the inter-agency convoy plan for the following month with inputs from sector members based on their mandate. The plan is then reviewed and endorsed by the Resident/Humanitarian Coordinator and submitted to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) for endorsement and approval.

The inter-agency convoy process was initially ad hoc as developing the plan and consolidating supplies was time-consuming. Endorsement and approvals were unpredictable and delivery of the convoys involved a very cumbersome process requiring authorisation at multiple levels. Because the plan targets UN declared besieged areas where initially no or few partners from cross-border operated, communicating the list of required supplies was often not smooth, as sharing information was not systematic and at times sensitive. There were also challenges in obtaining reliable information on the nutrition situation of women and children as there was no nutrition capacity inside UN declared besieged areas, with very limited or no trained health workers. This made substantial planning of an effective nutrition response very difficult. Despite these difficulties, the convoy process has gradually matured and become more predictable, with the development of monthly plans. Rapid nutrition assessments (using MUAC screening), observations and discussions with health workers are also now carried out by technical experts from Nutrition Sector partners and findings are used to inform convoy plans.

The proposed lists of locations and supplies are also now shared with other country hubs (Amman in Jordan and Gaziantep in Turkey) through the WoS structure for feedback and the resulting approved plan is shared by the Nutrition Sector with UN agencies (UNICEF, WFP and WHO) for their inputs (nutrition supplies). The final plan is then compiled and submitted to OCHA for further consolidation. This process is intensive, with a lot of communications back-and-forth, and many changes in locations and supplies; however, the result is a co-ordinated plan that avoids duplication and responds to real needs.

Cooperation has been greatly facilitated by the fact that a single HRP was introduced in the WoS approach that combined the separate response plans of all three hubs into a single document. Consequently, the Nutrition Sector had a well-coordinated response plan that covered the entire country from within Syria and encompassed cross-border operations. Information sharing, better synchronisation and regular exchange of experiences and ideas has since developed further, making coordination much more systematic.

The speed with which inter-agency convoys are delivered is not as rapid as intended in 2017 compared to 2016 due to the evolving security situation on the ground and the changing dynamics of the conflict in addition to cumbersome administrative procedures. However, efforts from the humanitarian community continue to address this.

Conclusions

Sector coordination in Syria has gone through various iterations since its establishment in 2013. Given the country context, coordination was not considered a priority in the early days of the conflict. However, with consistent advocacy from the cluster lead agency and other key UN sector partners, this view started to change and gradually the nutritional needs of the population were acknowledged. This led to the engagement of the relevant line ministry (MoH), SARC and UN agencies in establishing coordination mechanisms, identifying gaps in the response and mobilising potential partners to respond, with heavy investment in national capacity building on NiE. Over time, national NGOs also became fully engaged in the Nutrition Sector and are now a vital part of the coordinated response. Increased access of national partners to funding from UN agencies (UNICEF, WFP and WHO) in the sector has helped to scale up their response, although limitations in their operational and technical capacity in implementing large-scale interventions remain. In addition, national NGO partners are yet to access financial resources from the Syrian Humanitarian Fund (SHF) through OCHA.

In the absence of the WoS structure, cooperation between hubs was not taking place, which compromised operations in UN declared besieged and hard-to-reach areas. From the inception of the WoS approach, the Nutrition Sector made significant progress on various aspects, including harmonisation of tools, coordination of nutrition activities and representation of the sector at WoS strategic forums, including donor meetings. The WoS added value in terms of information sharing for decision making, avoiding duplication of efforts and capitalising on existing opportunities, while delivering cross-line and cross-border response. The presence of the WoS forum made the development of a single HNO/HRP response plan more systematic and easier.

The maturation of the Nutrition Sector and the development of the WoS approach has allowed a more systematic and coordinated response to the needs of women and children throughout the country, particularly in areas affected by the conflict such as East Aleppo, Ar Raqqa and, to some extent, Deir-e-zor. However, the sector still faces challenges that are affecting the response, including limited funding, inaccessibility to certain locations (including UN declared besieged and hard-to-reach areas) and difficulties in providing comprehensive nutrition support to IDPs in Raqqa and Hassakeh. Engagement and support of the WoS and improved collaboration of the three hubs in Syria, Jordan and Turkey are key to delivering a comprehensive and coordinated nutrition response in Syria.

For more information, contact: Muhiadin Abdulahi