Somalia Nutrition Cluster: integrated famine prevention package

By Samson Desie

Samson Desie is a nutrition specialist currently working as Nutrition Cluster Coordinator in Somalia with UNICEF. He has over ten years’ experience in managing large-scale and complex programmes in grassroots, national and international contexts, including in the South Sudan crisis situation, Sudan protracted emergency and Somalia.

The author gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the Global Food Security and Nutrition clusters; the Somalia Ministry of Health and Humanitarian Affairs; Somalia ICCG and OCHA; Somalia UNICEF, WFP, WHO, FAO, IOM and international/local partners implementing IERT, the affected population, and ENN.

The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this article are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of UNICEF, its executive directors, or the countries that they represent and should not be attributed to them.

Location: Somalia

What we know: Somalia was one of the focal countries identified in the Rome call for action on integrated programming to prevent famine.

What this article adds: Pre-Rome, an integrated approach – the Integrated Emergency Response Team (IERT) – was underway involving nutrition, health and WASH life-saving activities delivered by mobile teams to poor access areas. Post-Rome, significant funding was secured for the IERT and a package of food security support was integrated into the IERT. Challenges to implementing country actions have included lack of cross-sector guidance, protocols, and accountability frameworks; limited multi-sector capacity among partners; and resource gaps which hamper sector commitment to collective operations. Next steps include development of the IERT to broaden its remit (livelihoods and education); joint nutrition and food security assessment/analysis/planning; and development of common registries for internally displaced populations. Government is a key actor at state and federal level and a champion of the integrated multi-sector approach. To sustain momentum, the integrated approach should be a standing agenda in famine-prone countries.

Context

Somalia humanitarian needs continue to deteriorate and the risk of famine persists. Malnutrition levels have followed a deteriorating trend in recent years, with a steady increase in the number of malnourished children and number of internally displaced person (IDP) sites with malnutrition rates >15 per cent global acute malnutrition (GAM). At national level, median prevalence of acute malnutrition has steadily deteriorated from 12 per cent GAM in 2014 to 17.4 per cent in late 2017. Further data analysis conducted during the period 2007-2016 indicates that acute malnutrition trends in Somalia persist at GAM/severe acute malnutrition (SAM) emergency thresholds, with further deterioration.

Currently we are witnessing a significant deterioration in the malnutrition situation among IDPs and host communities, driven by high morbidity (disease incidence; e.g. acute watery diarrhoea, measles), low humanitarian support, poor child feeding and caring practices, food insecurity, limited health service availability (poor expanded programme on immunisation (EPI) coverage), increased morbidity, poor health-seeking behaviour, and difficulty in accessing clean water supplies. Overall, Somalia has endured a persistent complex emergency resulting from continued conflicts, displacements, drought and disease.

Against this backdrop and elevated risk of famine, in early 2017 the Rome plan of action was initiated at the global level through global nutrition and food security clusters alongside the lead agencies. Somalia was one of the focal countries.

Pre-Rome country actions/initiatives

Pre-Rome country actions/initiatives

The country Inter-Cluster Coordination Group (ICCG) had already initiated an integrated approach – the Integrated Emergency Response Team (IERT) – with a focus on three key life-saving clusters – Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), Health and Nutrition – to deliver services in a mobile team approach to some of the inaccessible remote areas. The approach with clear operational guidance was endorsed by the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) in March 2017. The key objective of the IERT is to ensure access to integrated life-saving health/WASH/nutrition services of vulnerable and most affected communities in rural areas and villages of Somalia. For WASH it involves delivery of key WASH activities, services and a hygiene kit; for health, provision of primary services (mainly to children under five years of age and mothers); and for nutrition, acute malnutrition identification and treatment on the spot (see Box 1). The teams comprise health professionals and paramedics identified from main urban cities who were provided with refresher training on key functions and deployed to affected sites, including the rural villages of Bay, Bakol, Gedo, Lower Shebelle, Lower and Middle Jubba. Accordingly about 50 IERTs were deployed to four of the most affected regions1 in Somalia selected based on the need, accessibility, existence of basic services and presence of IDP camps. The team reached about 45,000 beneficiaries with life-saving nutrition, health and WASH services2 during the initial short period of deployment time (April-Mid May 2017).

Box 1: Core functions of IERTs

Case management

• Provide basic life-saving medical services, including acute watery diarrhoea (AWD)/cholera patients.

• Ensure accurate, documented patient history.

• Follow strict case management of AWD/cholera.

• Practice strict infection control.

• Treat uncomplicated malnourished cases (both moderate and severe acute malnutrition (MAM/SAM).

Referral

• Identify, provide first aid service and refer patients with medical complications requiring admission to health facilities.

• Referral of complicated cases of malnourished children to appropriate services.

Health education, sanitation and hygiene promotion

• Support community hygiene promotion for AWD/cholera prevention.

• Promote good hygiene and sanitation practices to affected communities.

• Breastfeeding promotion and infant and young child feeding support.

Community-based work in remote areas

• Identify and train community volunteers on health education.

• Mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) screening and identification of malnourished children.

• Danger sign identification of malnourished children with medical complications and use of appetite test.

WASH

• Organise community sensitisation and mobilisation sessions at facility and outreach levels of the affected areas.

• Distribute standard information, education and communication (IEC) materials for social mobilisation.

• Closely coordinate with those involved in activities in the community, regional and district levels, including NGOs, social mobilisers, elders and sheikhs.

• Strengthen the Case Tracing Model and support implementation at facility treatment centres.

• Strengthen capacity of partners for hygiene promotion. Continuous follow-up and refresher trainings and/or mentoring in the field to build partner capacity.

Nutrition

• MUAC screening for all children aged 6-59 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW).

• Treatment of MAM and SAM without medical complications.

• Referral of MAM and SAM cases with medical complication and failed appetite test.

• Breastfeeding promotion.

Post-Rome actions and progress to date

The Rome call for action has significantly catalysed change around integrated programming in Somalia. It is now the primary driver of the integrated agenda and has been crucial to securing donor acceptance and buy-in; many donors are now using it to push partners to implement the approach. Significant cluster actions on integrated programming have taken place since Rome, besides continued/maintained IERT responses. A series of events took place at country level to secure buy-in (Box 2) and act on the country action plan (Box 3), the release of which coincided with the Rome call for action in May 2017; this in turn strengthened the case for implementation. Buy-in involved consultations at various levels and across sectors to secure high level and cross-agency (UNICEF, WFP, FAO) endorsement of the country plan of action.

Box 2: Country-level buy-in to action plan

- Global meeting lead by executive directors in Rome – 25/26 April 2017/Global call for action – May 2017.

- Somalia lead agencies, partners and ICCG consultation with development of plan of action (POA) – May 2017.

- Somalia IERT and FSN Initiative – May 2017.

- Briefing partners, lead agencies (UNICEF, FAO and WFP) and ICCG on the initiative.

- Success in securing Somalia Humanitarian Funds (SHF) funding to implement the IERT – WASH, Health and Nutrition.

- Somalia Nutrition Cluster and Food Security Cluster (FSC) finalised plan of action and shared with three lead agencies.

- Somalia Nutrition Cluster and FSC work on joint priority areas with help of FSNAU.

- The FSC consolidates the protocol and package of the IERT in Somalia to complement the ongoing initiative of the IERT of Nutrition, WASH and Health clusters.

- Current allocation of SHF (12 million) predominantly for support of the IERT where FSC component is integrated into the three-cluster initiative.

Box 3: Country action plan

- Joint response analysis and identification of priority areas for integrated responses.

- Map ongoing and planned responses and gap identification in priority areas, including revision of existing response plan as necessary.

- Identify mutual partners for implementation of revised/integrated response plan in gap areas while building on any existing consortia and/or supporting establishment of a new consortium where there is limited capacity around multi-sector programming.

- Define joint targeting criteria and ensure use of a common platform for data capture, including use of SCOPE and Common Registration. It was agreed to target families of malnourished children with food security/livelihood intervention if they are not already enlisted.

- Support and integrate nutrition-sensitive programming, mainly involving WASH, Health, Food Security and Livelihood interventions in joint areas.

- Engage WASH Cluster and Health Cluster on the integration plan.

- Expand the scope of the current IERT to include FSC-related responses.

- Strengthen linkages between WASH, FS, Nutrition and Education response.

- Introduce multiple use of water at household level to cater for livestock water needs, which is as important as water for human consumption given dependence of pastoralist livelihoods on livestock.

- Develop priority interventions aligned with seasonal calendar across the Nutrition, WASH, Health and FS clusters in an integrated manner.

- Advocate for multi-sector HRP at HCT level based on lessons learnt.

- Capacity development of partners regarding multi-sector programming.

- Ensure centrality of accountability to affected populations (AAP), protection and gender-based violence (GBV) mainstreaming.

- Secure financing for joint programming.

A key development was integration of food security into the IERT. The Somalia nutrition and FSC worked on joint priority areas, consolidating the protocol and package of food security components for inclusion. In the country plan of action, two key initiatives were prioritised to prevent famine:

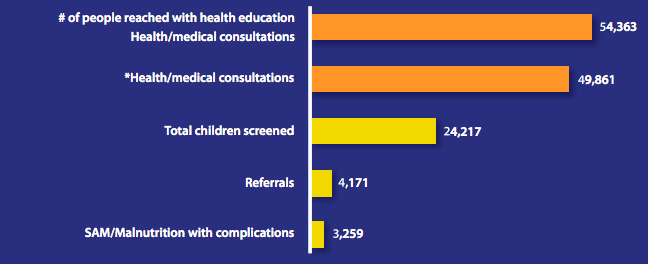

1. Secure support for the IERT. Post-Rome, the IERT has received huge support from the HCT and has received two rounds of funding (US$6.5 million and US$11 million). The IERT reached over 135,000 beneficiaries during May to July 2017 (see Figure 1).

2. Food security and nutrition integration has involved two key actions:

a) All families identified with a malnourished child receive a one-month food security package.

b) Outpatient therapeutic programme (OTP) discharge package. The discharge package now provides a food security package for a minimum of three months after discharge and food security programmers provide food for all caretakers for inpatient units while a child is admitted.

Figure 1: Somalia IERT services delivered, May to July 2017

Government is a key actor at state and federal level, from planning to implementation and monitoring, and a champion of the integrated multi-sector approach. The creation of the new Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs has brought added benefits in creating streamlined contacts/processes (dispensing with the need to engage with multiple ministries), a permanent cluster member and a full-time presence in the drought operations coordination centre. Monitoring and IERT team supervision are implemented by the Ministry of Health. Planning (where and by who) is undertaken by government at state and federal levels.

Key challenges, context and lessons learned

The major key challenge faced involves the protocols, standards and quality assurance of an integrated multi-sector response plan and its implementation in the absence of clear guidance, common accountability and results framework at all levels. Field manuals are sector-specific and heavily detailed; simplification is needed to make integration feasible at ground level. Moreover, there was limited capacity for a multi-sector integrated approach, compounded by resources mobilisation challenges. There have been issues around sensitivity to organisational mandate versus collective approach on integration; agencies have sector-specific mandates and agendas that may conflict with an integrated approach. There have been some challenges relating to exclusion, clan affiliation and government promotion of partners to access pooled funding who have not been risk assessed/cleared for funding; UNICEF negotiates and refers such issues to the Humanitarian Coordinator or to OCHA as necessary. These issues have not been major obstacles to services being implemented. There have also been capacity limitations: funding is channelled through local partners who have sector-specific specialities that limit planning and implementation of multi-sector approaches. Most of the challenges are being addressed as follows:

- Working through consortia that bring together different expertise to overcome capacity constraints;

- Development of a simplified field manual on bringing together key sectors;

- An online monitoring tool is being supported by WHO to assure and monitor quality (this is in the early stages of development); and

- Discussion underway on how to develop accountability and a results framework across sectors. Currently, results are monitored using sector-specific frameworks.

This intensive collective effort galvanised by the Rome call for action has proved it is possible to implement a multi-cluster integrated response in the context of famine prevention. Donor and lead agency support is crucial to achieving this, while government buy-in and partner commitment are also critical.

Next steps

The IERT terms of reference will be broadened and renamed to reflect learning to date and to ensure inclusion of other clusters. The focus for immediate development of this approach is inclusion of FSC and livelihood packages and presentation of the revised, integrated response package; plan, map, identify affected population and ways forward to a joint-cluster strategic advisory group (SAG) meeting and the ICCG for review and endorsement. An oversight committee from the three lead agencies (UNICEF, WHO, WFP) will then be established to guide and support implementation.

Joint response/gap analysis will be conducted for priority areas to use in advocacy and planning. Maps will be developed to show where key sectors overlap, who is doing what and where, and gaps. Potential partners will be identified that can fill the gaps; this may involve existing or new consortia and securing joint financing for implementation. To that end, a merger between the food security technical working group (WG) and the nutrition cluster assessment management information WG is underway, so that only one team is appraising information; this will be the highest authority looking at nutrition information to guide interventions.

A new initiative under development is a registration task force for developing a common registry. While there are lots of IDPs, there is no systematic database/tracking system in place. The aim is to have a common database across clusters and actors to generate quality data and make more efficient use of resources. The newly activated Camp Management Cluster (CCM) is leading on this.

In terms of global requirements to support integrated programming in Somalia, there is a need to broaden the narrow focus of agencies and partners to a wider perspective of integrated programming through continuous follow-up, monitoring and support. Efforts should not stop at the call for action: to sustain momentum, the integrated approach should be a standing agenda in famine-prone countries. Documentation of lessons learnt and development context-specific guidance for scale-up efforts is also needed. The support of the global Nutrition Cluster team to monitor progress and guide country challenges is crucial. Brief updates/bulletin reports should be provided to the global humanitarian committee/ action.

For more information, contact: Samson Desie

Endnotes

1These are SWS(All), JL (Gedo and Middle Jubba), PL/SL (Sool, Sanaag), Galmudug (South Mudug and North Galgadud) and Benadir region (IDP camps).

2Services include AWD/cholera, ARI, pneumonia, UTI/others, AFI/malaria, child screening, SAM/malnutrition with complications, referrals and ANC.