Yemen Nutrition Cluster: Integrated famine-prevention package

By Anna Ziolkovska

Anna Ziolkovska is currently the Nutrition Cluster Coordinator in Yemen. Anna has a PhD and more than ten years’ experience in nutrition, humanitarian assistance, cluster coordination, information management, capacity building and project management, both at HQ and country-levels, including in South Sudan, Somalia, Philippines, Ukraine, Afghanistan and Yemen.

The author would like to acknowledge the input of the Food Security and Agriculture Cluster (FSAC) Coordinator (Gordon Dudi), who co-led the prioritisation process with the Nutrition Cluster Coordinator. The author would also like to acknowledge the contributions of the nutrition, health, WASH and FSAC partners, their respective Cluster Coordinators and Strategic Advisory Groups (SAGs), the Nutrition Cluster Assessment Working Group, relevant ministries and the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), as well as support from the Humanitarian Coordination Team (HCT) in the development and implementation of the integrated famine-prevention package.

Location: Yemen

What we know: There has been escalation in conflict in Yemen since 2015, with 20.7 million people in need of assistance, and risk of famine.

What this article adds: Before the Rome meeting call for action to prevent famine, the Nutrition and Food Security and Agriculture Cluster (FSAC) collaborated to prioritise locations at high risk of famine and in need of a joint minimum response package. Post-Rome, country-level actions were collaboratively identified by Nutrition, FSAC, Water, Sanitation and Hygiene and Health Clusters. The process since has been led by the Nutrition Cluster. Ongoing activities include adaptation of SMART to integrate indicators from other sectors and a joint chapter on famine prevention in the humanitarian needs overview and in the humanitarian response plan. Imminent plans are to agree on joint analysis and integrated package of interventions for priority districts. Commitment for joint funding has been secured. Challenges to integrated programming include lack of recent district-level mortality and sector data; collapsing health systems (coupled with large cholera outbreak); and lack of partner capacity on integrated programming, among others. Country-led process is key. High-level advocacy by the Global Nutrition is critical to ensure country-level management commitment.

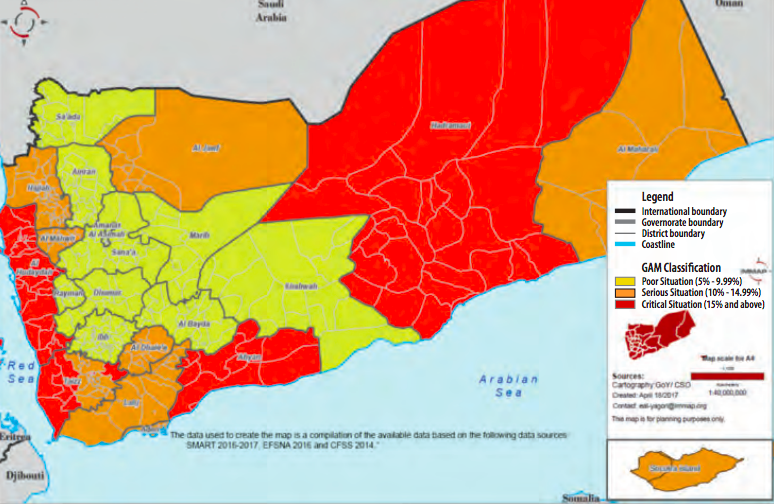

Context

There has been an escalation in conflict in Yemen since March 2015; there are now over two million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and an estimated 20.7 million people in need of humanitarian assistance out of a total population of 27.4 million. An estimated 17 million people (60 per cent of the overall population) are food insecure, 10.2 million of whom are classified under the Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) as in ‘crisis’ (phase 3) and 6.8 million in ‘emergency’ (phase 4). Figure 1 shows the classification of governorates in Yemen according to prevalence of global acute malnutrition (GAM). Prevalence of acute malnutrition is high, with an estimated 400,000 children under five years of age with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and 1.8 million children under five year with moderate acute malnutrition (MAM). An estimated 14.5 million people need support to meet basic water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) needs and 14.8 million require assistance to ensure adequate access to healthcare. According to the health resources availability mapping system (HERAMS) only 50 per cent of health facilities are currently fully functional. Cholera is also a problem, with more than 750,000 suspected cases as of October 2017.

Figure 1: Nutrition Cluster GAM classification, Yemen (April 2017)

Nutrition Cluster in Yemen

Nutrition Cluster in Yemen

The Nutrition Cluster approach was adopted in Yemen in August 2009 immediately following the outbreak of the sixth war between government forces and the Houthis in Sa’ada governorate in northern Yemen. Since then, Yemen has continued to face complex emergencies that are largely conflict-generated and in part, aggravated by civil unrest and political instability. The Nutrition Cluster has been constantly active during this time. Following the escalation of the conflict in March 2015, a Level three system-wide emergency was declared in Yemen, which is still in place today.

The Nutrition Cluster is currently established at national level, with five sub-national clusters at the zonal level in Hodeidah, Ibb, Aden, Saada and Sanaa. The Cluster is co-led by the Ministry of Public Health and Population (MoPHP) and UNICEF and consists of 32 partners, including United Nations (UN) agencies, MoPHP, and national and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs). A Strategic Advisory Group (SAG) provides strategic directions to the Cluster, while three technical working groups (TWGs), on infant and young child feeding (IYCF), community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) and assessments, support partners in these specific areas.

Nutrition priorities

According to the 2017 humanitarian response plan (HRP) developed at the end of 2016, the nutrition objectives in Yemen are as follows:

- Deliver quality, life-saving interventions for acutely malnourished children and pregnant and lactating women (PLW);

- Contribute to prevention of malnutrition by enhancing the blanket supplementary feeding programme, micronutrient support, deworming, and infant and young child feeding (IYCF) support;

- Strengthen the capacity of relevant authorities and local partners to ensure an effective, decentralised nutrition response; and

- Ensure a predictable, timely and effective nutrition response through needs analysis, monitoring and coordination.

There has been a clear shift towards integrated (multi-sector) nutrition programming in 2017 following the IPC classification of acute food insecurity in Yemen in February 2017. As the risk of famine rose, there was widespread realisation of the complexity of the situation that is not only related to malnutrition, but also to underlying causal factors. The immediate link to food security was clear, given that the indicators of famine used by the IPC technical committee are in large part related to food security (mortality + prevalence of GAM + food consumption or livelihood change or documented inference analysis based on at least four pieces of somewhat reliable evidence (direct or indirect) on food security contributing factors or outcomes).

Country buy-in to integrated workplan

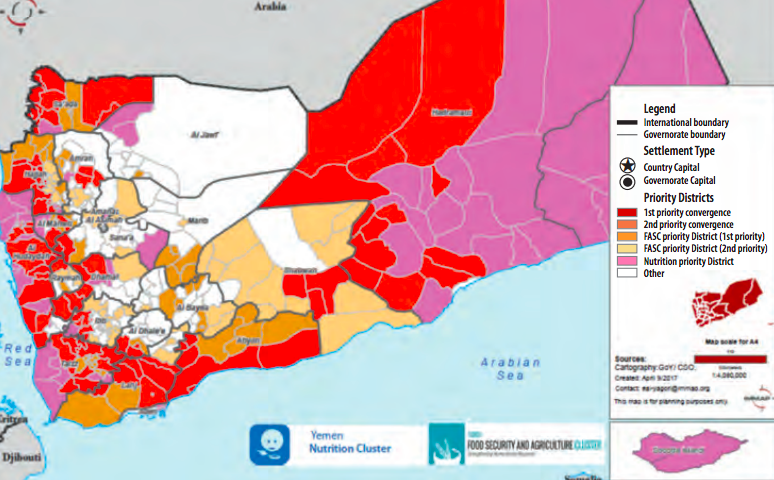

The integrated response began in Yemen prior to the joint Global Food Security Cluster (GFSC) and Global Nutrition Cluster (GNC) meeting on 26 April 2017 in Rome. Initially the process in Yemen was led by the Nutrition Cluster and FSAC, which resulted in the prioritisation of locations at high risk of famine (see Box 1) and development of a joint minimum response package (Figure 2). Seventy-seven districts have been identified as high-priority districts based on the selected cut-off points. Additionally, 18 districts were upgraded to high-priority districts following discussions with partners of both clusters at field and national levels. If only one threshold was reached (more than 15 per cent GAM or more than 20 per cent of population severely food insecure), the districts were assigned as priorities for the relevant sector only (Nutrition Cluster or FSAC).

Box 1: Prioritisation of locations at high risk of famine

The following indicators were used for prioritisation: GAM prevalence (based on SMART surveys 2016-2017, emergency food security and nutrition assessment (EFSNA) 2016 and a comprehensive food security survey in 2014), and percentage of food-insecure population (based on the IPC March 2017 and EFSNA 2016). There was a need to prioritise districts for nutrition and food security interventions within governorates; however there was a lack of representative district level data to base this on. As a result districts were clustered by livelihood zone, agro-ecological zone and elevation, and the proportion of GAM cases in the new clusters was recalculated. The resulting percentages used for prioritisation do not provide GAM prevalence rates for the clustered districts, but represent the proportion of children with GAM from the total number of children measured. This provides an indication of the severity of the situation in that area. Cut-off points for each category were assigned based on the international thresholds where possible, taking into account the local context.

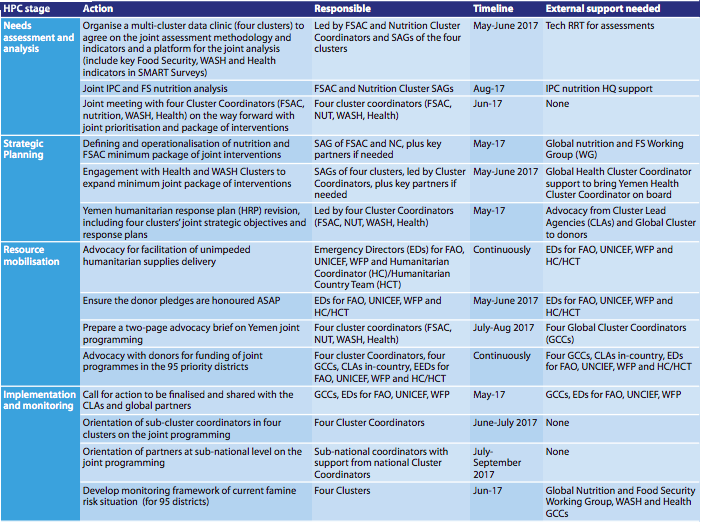

Following the Rome meeting, the Nutrition Cluster and FSAC also brought the WASH and Health Clusters on board. The group chose not to use the Rome-generated country action plan as this was perceived as being developed by two Cluster Coordinators (Nutrition Cluster and FSAC) without consultations with any partners and without engagement of the other two clusters (WASH and Health). Instead, the group agreed a way forward with all four Cluster Coordinators and four Strategic Advisory Groups (SAGs). The country action plan developed in Rome has been largely followed and is described in Table 1. Advocacy from the Rome meeting, including the ‘call for action’ and letter from the Emergency Relief Coordinator (ERC), supported the process to ensure management and humanitarian country team (HCT) buy-in.

Figure 2: Joint prioritisation of famine-prevention locations

Table 1: Yemen plans for scaling up integrated nutrition programme

Table 1: Yemen plans for scaling up integrated nutrition programme

Progress to date (September 2017)

Progress to date (September 2017)

The process has been led by the Nutrition Cluster, which was identified by the collective to take this forward. To date, the way forward has been agreed by all involved. Adaptation of the SMART guidelines to the Yemen context is ongoing, including a review of the standard SMART questionnaire used in the country to ensure that information from/for Health, WASH and FSAC is incorporated. A joint chapter on integrated programming for famine prevention to incorporate the humanitarian needs overview and the HRP is in progress. At the time of writing (October 2017), a joint meeting of the four cluster SAGs, relevant technical ministries, sub-national coordinators and the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) was scheduled to agree on the four-clusters integrated minimum package of interventions for the priority districts. The meeting was due to reach agreement on the joint needs analysis and the development of a joint minimum package of interventions and its implementation modalities. Commitment for joint funding has been secured, with a dedicated envelope allocated from the Yemen Humanitarian Pooled Funds in 2017 to address the underlying and immediate causes of food insecurity and malnutrition by ensuring adequate access to food, nutrition, health and WASH by the most vulnerable through an integrated approach. Similarly, many donors are showing interest in funding integrated programmes in the priority districts.

Challenges

There have been challenges in the process of planning and implementing integrated programming in the context of famine prevention. For example, there is a lack of recent mortality data – one of the main indicators for declaring famine and for geographical prioritisation – for Yemen. There is also a lack of district-level nutrition, WASH and health data, making it difficult to monitor changes in the priority geographical locations efficiently. The collection of nutrition information even at governorate level is challenging: necessary permissions from appropriate authorities are required and there are access constraints. Baseline population is not standardised, as clusters use different approaches to calculate population. For example, some use adjusted population for population movements while others use non-adjusted projections issued by the Central Statistics Organisation.

Health facilities are on the verge of collapse; according to the health resources availability mapping system (HERAMS) in 2016, only 50 per cent of health facilities are fully operational. This is exacerbated by the non-payment of salaries to health workers for over one year, with many leaving to look for alternative income sources.

Yemen is currently site of the biggest cholera outbreak in the world, which has diverted attention of the HCT away from the nutrition needs of the population, as well as the attention of the WASH and Health Cluster Coordinators, who are fully engaged in the cholera response.

The fact that many of the partner agencies are cluster/sector-specific, with little capacity for joint programming, is another impediment to integrated programming. One of the suggested ways to overcome this is for partners to connect with agencies from other clusters working in the same geographical locations and submit joint projects; however this is still in early/pilot phase. The heavy focus on integrated programming has had a negative impact in terms of disregard of nutrition-only priority locations, where the malnutrition situation is also critical but for reasons unrelated to food security.

Lessons learned

The process should be country-led in order to ensure buy-in to integrated programming, with the clear willingness of clusters (and cluster coordinators) to contribute time to the discussions with a desire to move the agenda forward. While each cluster is finding its own way to prioritise and plan its response based on the limited information it has, it remains difficult to ensure joint planning, given the limited availability of information on which to base decisions. Global Cluster engagement in high-level advocacy is needed to ensure management commitment. For example, post-Rome advocacy with management and the HCT has been instrumental in lending profile to the initiatives and helping catalyse multi-cluster engagement and commitment. Constant sensitisation of partners on joint response is needed in order to ensure understanding and buy-in of cluster partners to integrated programming. There is a need to explore how to develop the capacity of partners to expand programmes to other technical areas to ensure that programmes are integrated at ground level and to discover ways for several NGOs with different expertise to work together.

Next steps

SMART assessments must now be scaled up in Yemen and joint IPC and nutrition analysis carried out. The joint response package must be operationalised at sub-national level. The Yemen HRP is currently in development and continued advocacy is required for joint planning, resource mobilisation and response. At the global level support is needed to facilitate the inter-cluster workshop in Yemen on joint programming with all four clusters. GNC partners should reflect on their capacity for joint four-clusters programming and on the changes to be implemented at organisational level to allow this. Support (both technical and in terms of human resources) in Yemen is needed for international NGOs and UN agencies and to ensure constant monitoring of their performance.

For more information, contact: Anna Ziolkovska