Getting on the same page: Reaching across disciplinary boundaries to improve nutrition

By Lidan Du and Heather Danton

Lidan Du is a public health nutritionist with a PhD in international nutrition from Cornell University and over 15 years’ experience in international nutrition research. She joined Helen Keller International in 2013 as the Research Advisor of the Food Security and Nutrition team of the SPRING project.

Heather Danton is an agriculture and food security expert. She is the Director for Food Security and Nutrition at John Snow, Inc., where she leads efforts to improve linkages between agriculture and nutrition on the SPRING project. She has 30 years’ experience of working in food security and livelihoods in Asia, Africa and Latin America, including as the Senior Director of Food Security and Livelihoods for Save the Children Federation.

The multi-sector nature of the global malnutrition problem has been made widely known since the publication of UNICEF’s Conceptual Framework of Malnutrition (UNICEF, 1990). Nutrition has since been elevated in policy agendas; it is one of the three high-level objectives of the US Government’s Global Food Security Strategy being implemented through the Feed the Future initiative and features prominently in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (SDG 2 particularly). In fact, nutrition is related to all SDGs (Webb, 2014).

In our work on USAID’s multi-sector nutrition project, Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING), our key task is to build evidence and provide assistance to help countries deliver better nutritional results from agriculture and economic development initiatives supported by the Global Food Security Strategy. Agriculture is one area that offers opportunities for nutrition-sensitive interventions (Ruel and Alderman, 2013). However, existing evidence has yet to prove the impact of nutrition-sensitive agriculture programmes on reducing child stunting, a commonly used nutrition indicator (Webb and Kennedy, 2014).

Researchers at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) reviewed and highlighted results from nutrition-sensitive agriculture programmes implemented and reported on since 2014 and identified several knowledge gaps and research priorities (Ruel et al, 2018). Through the programmes that SPRING has been supporting, we have repeatedly observed two of the issues that Ruel et al pointed out in their review. One is the failure to explicitly consider pathways linking agricultural (inputs) to nutrition (outcomes) in programme and research design. The other is the lack or inappropriate use of metrics to demonstrate links between agriculture and nutrition.

At SPRING we recommend that agriculture and economic growth projects mandated to contribute to nutrition adopt an explicit programme impact pathway to inform their monitoring systems to both define and track progress toward realistic nutritional outcomes. However, such a recommendation does not necessarily translate easily with sector specialists, even when intentions toward multi-sector coordination and collaboration are desired and required.

Why is working across sectors so hard?

One of the keynote speakers at the Agri-Chain & Sustainable Development conference in Montpellier, France in December 2016 shared her perspectives on the challenges of multi-sector integration and how a better mutual understanding could help the agriculture and nutrition sectors to work better together. She proposed four key directions of opportunity and change: inter-sectorality; inter-disciplinarity; trans-disciplinarity; and partnered research. Her key argument under inter-disciplinarity pointed to the need to overcome barriers in languages, concepts, assumptions and styles of working across different disciplinary backgrounds.

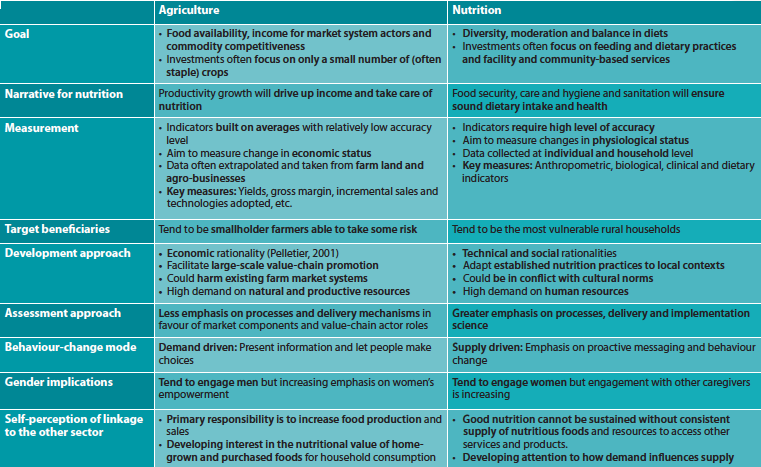

This inter-disciplinarity argument led us to reflect on our own experiences and observations working across disciplines and sectors. Our deliberations centred on the technical characteristics that are so deeply entrenched in the respective disciplines of agriculture and nutrition – from training to application of knowledge to the differing ways in which we work. We agree that these difficulties are related to some of the fundamental differences in our paradigms. We compiled a list (Table 1) to help articulate the gaps in our shared vision and objectives; to come up with solutions and strategies to close these gaps; and explore where and how we can apply our comparative advantages to strengthen collaboration.

Table 1. Disciplinary differences between agriculture and nutrition practitioners/researchers

This paper discusses some of the challenges posed by disciplinary paradigms that often hinder technical staff from working effectively in a multi-sector fashion. It is also important to note that while the silos created by disciplinary imperatives may ensure a high level of technical rigor and often respond to funding priorities of donors or governments, similar challenges of sector silos also permeate government and donor institutions; yet the households and individuals that our programmes work with rarely perceive themselves as living in sector or disciplinary siloes.

How do we solve this dilemma? We offer a few thoughts below, based on our work with mostly large-scale value chain and market systems development projects. We welcome inputs from other experts and practitioners to enrich this discussion (see contacts at the end).

- In addition to responding to the demand of end markets which may be located far from areas of production, the selection of nutrient-rich value chains for agricultural investments should also take into account – and attempt to mitigate – known nutritional deficiencies prevalent among smallholder producer households. Value-chain assessments conducted for economic growth activities should include an understanding of nutritional needs so that programmes can measure the extent to which growers and their families are able to receive some nutritional benefits from the production.

- An explicit nutrition-sensitive agriculture programme theory of change is needed in the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of agricultural value-chain projects to generate much-needed evidence. Quantitative and qualitative data should be collected to narrow in on the key facilitating and inhibiting factors that are at play along the multiple agriculture-to-nutrition pathways (Herforth and Harris, 2014).

- Efforts are needed to better understand and respect differences in programme approaches, priorities and paradigms; establish a common language to communicate across disciplines; and develop consensus on how disciplines complement each other in multi-sector programing, especially at government and donor levels. This will begin to break down the inter-disciplinary barriers that prevent multi-sector programming from being truly effective and to facilitate policy, planning and funding that will support sustained outcomes for nutrition.

- Special efforts must be made to check the many (often unchecked) assumptions along each and every step of the agriculture-to-nutrition pathways so that they are clearly spelled out in programme theories.

SPRING is developing a training resource package and guidance (to be released in May 2018) that will serve as tools for implementers to improve multi-sector programme design and maximise results for nutrition – stay tuned!

For more information or to contribute to this discussion, contact Lidan Du, Heather Danton or post a question on en-net.