Scale-up of IMAM services in Afghanistan

By Ahmad Nawid Qarizada, Piyali Mustaphi, Jecinter Akinyi Oketch and Shafiqullah Safi

Ahmad Nawid Qarizada is a Nutrition Specialist for UNICEF Afghanistan. He is a medical doctor with a post-graduate diploma in nutrition, a Master’s degree in public health and over seven years’ experience working in public health nutrition with government, United Nations agencies and international non-governmental organisations.

Piyali Mustaphi is the Chief of Nutrition for UNICEF Afghanistan. Has over 25 years’ experience in humanitarian and development nutrition programmes, including 20 years’ experience with UNICEF in South Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

Jecinter Akinyi Oketch is a Nutrition Specialist for UNICEF Afghanistan with over 15 years’ experience in the management of nutrition programmes in development and humanitarian contexts at national and international levels in Africa and South Asia.

Shafiqulla Safi is an Integrated Management of Acute Malnutrition Senior Officer with the Ministry of Public Health of Afghanistan. He is a medical doctor with a post-graduate diploma in public nutrition and has over nine years’ experience working in public health and nutrition with national and international non-governmental organisations.

Location: Afghanistan

What we know: While there has been progress on stunting reduction in Afghanistan, the prevalence and caseload of acute malnutrition remain high.

What this article adds: Since 2003, the Government of Afghanistan has provided strategic direction on public health nutrition. Current strategy and plans include 2020 targets to increase coverage of acute malnutrition (80 per cent target) through nutrition and health interventions. Integration of treatment services in the Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS) and Essential Package of Hospital Services is considered the means to sustainable scale-up. In 2015 and 2016, an action plan to scale up integrated management of acute malnutrition (IMAM) across the country was implemented. By 2017, the IMAM programme was scaled up in all 34 provinces and nearly 78 per cent of districts had at least one component of the IMAM programme. Overall programme performance exceeded Sphere standards, with some provincial exceptions. Bottleneck analyses in 2015 and 2017 identified good progress but ongoing challenges, including ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) stockouts, low outpatient department integration in BPHS and inadequate community health worker training on screening. Actions to address these bottlenecks and monitoring continue. Other plans underway to support quality scale-up include: integration of routine RUTF supply provision within longer-term projects and funding mechanisms; comprehensive capacity building by Ministry of Public Health with technical support from UNICEF, World Health Organization and World Food Programme; further scale-up in high-burden, low-coverage provinces; and IMAM integration into mobile teams in hard-to-reach areas.

Background

In Afghanistan an estimated 55 children under five (U5) die for every 1,000 live births (DHS, 2015), a major risk factor for which is malnutrition. Despite improvements in some nutrition indicators over the last decade, such as a reduction in stunting prevalence from 60.5 per cent in 2004 to 40.9 per cent in 2013, global acute malnutrition (GAM) has risen (from 8.7 per cent to 9.5 per cent over the same period) (NNPS, 2013). There is significant variation between provinces in rates of stunting (ranging from 24.3 per cent in Ghazni to 70.8 per cent in Farah) and wasting (ranging from 3.7 per cent in Faryab to 21.6 per cent in Uruzgan). In 2013, eight provinces had wasting prevalence above the 15 per cent World Health Organization (WHO) emergency threshold.

More recent surveys based on weight-for-height z-scores (WHZ) show continued high rates of acute malnutrition. In Farah province in 2017, prevalence of GAM and severe acute malnutrition (SAM) among children U5 was 10.8 per cent and 1.2 per cent respectively (SMART survey, 2017) and, in Kandahar, was 8.3 percent and 1.3 percent respectively (SMART survey, 2017). Childhood illness (in particular diarrhoea and acute respiratory infections) and underlying poor sanitation and environmental conditions remain key drivers of acute malnutrition in the country, as well as sub-optimal breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices among infants and young children. In 2013, only 58.4 per cent of infants under six months were exclusively breastfed and 41.3 per cent of infants age 6-8 months were being given solid, semi-solid or soft foods (MoPH, 2013).

Nutritional risks and vulnerabilities among young children and pregnant and lactating women (PLW) have been exacerbated by conflict-driven displacements that have disrupted livelihoods. In 2017, conflict spread particularly to the north, northeast, and east of the country, with nearly 150,000 people newly displaced as a result (FEWSNET, 2017). Increased conflict has also reduced humanitarian access, including to life-saving and preventative nutrition services, lowering programme coverage and sustaining high levels of acute malnutrition in internally displaced persons (IDP) camps and conflict-affected provinces. According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees and the International Organization for Migration, an estimated 32,593 documented and 218,218 undocumented people returned to Afghanistan from Pakistan and Iran during the first half of 2017, often returning to contexts with widespread conflict and displacement and limited livelihoods opportunities. Children and PLW in this population are at higher risk of malnutrition. For this reason, the nutritional needs of returnee and refugee population groups are a priority for the Afghanistan Nutrition Cluster.

National Nutrition Strategy in Afghanistan

National Nutrition Strategy in Afghanistan

When the Public Nutrition Department (PND) was established in 2003, the first National Nutrition Policy and Strategy (NNPS) for Afghanistan was developed for the period 2003 to 2006 to guide the nutrition-related work of the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH). This document adopted a public nutrition approach, based on the UNICEF conceptual framework of malnutrition. To address subsequent priorities and challenges, the NNPS was revised for the period 2009 to 2013. Eight strategic priorities were proposed, which were later integrated into the MoPH Strategic Plan for 2011-2015 (see Box 1).

Box 1: Strategic priorities for the Afghanistan National Nutrition Policy and Strategy, 2009-2013

- To advocate for and increase awareness of healthy eating among the general population;

- To reduce the prevalence of major micronutrient deficiency disorders, in particular iron, folic acid, iodine, vitamin A and zinc, throughout the country and prevent possible outbreaks of vitamin C deficiency illnesses such as scurvy;

- To strengthen case management and increase access to quality therapeutic feeding and care at health facility and community levels;

- To ensure that all commercial and home-produced foods are safe for consumption;

- To monitor the nutritional situation in Afghanistan and strengthen the monitoring and evaluation of nutrition strategies and programmes to inform development planning and emergency responses;

- To ensure that responses to treat and prevent moderate acute, severe acute and chronic malnutrition are timely and appropriate and that increases in moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) and SAM are effectively managed;

- To increase the percentage of child caregivers adopting appropriate IYCF practices; and

- To strengthen in-country capacity to assess the nutrition situation and design, implement, monitor and evaluate public nutrition interventions.

The Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (GoIRA) has expressed its commitment to enhancing food and nutrition security for the Afghan people in several policies, strategies and programmes and in the signing of several international covenants. In 2012, the GoIRA developed the Afghanistan Food Security and Nutrition Agenda (AFSeN). Its objectives were to assure the availability of sufficient food for all Afghans; improve economic and physical access to food, especially by vulnerable and food insecure population groups; ensure stable food supply over time and in disaster situations; and promote better diets and adequate food utilisation, particularly among women and children.

In 2015, the NNPS was updated in line with this for the period 2015 to 2020, with intermediate results around increased access to nutrition services and products; improved nutrition behaviours and practices; improved quality of nutrition services and products; and a strengthened social, regulatory and political environment for nutrition. Significant attention is given in this strategy to improving coverage of acute malnutrition services. Included as a key indicator under the first intermediate result is “increased access to and availability of nutrition services and products”, with a treatment coverage target for children U5 with acute malnutrition of 80 per cent in 2020, compared to 34 per cent at baseline in 2015.

Strategic approach to acute malnutrition management in Afghanistan

The GoIRA strategy to achieve 80 per cent coverage by 2020 is to ensure a continuum of care through the implementation of complementary health and nutrition interventions. The PND/MoPH is also strengthening the implementation of public nutrition within a Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS) and an Essential Package of Hospital Services (EPHS) by encouraging and supporting innovations in nutrition-specific services; developing necessary guidelines, standard operating procedures and job aids for BPHS/EPHS staff; and providing technical support through training, regular assessments, monitoring, supportive supervision and mentoring.

The GoIRA has expressed commitment towards a multi-sector approach through the AFSeN 2012 and the MoPH is promoting a multi-sector approach to tackling malnutrition by encouraging cooperation across government sectors to strengthen the effectiveness of the national nutrition strategy. Support has been given to the MoPH from Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Livestock (MAIL), Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs, Martyrs and Disabled (MoLSAMD), Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation Development (MRRD), and Ministry of Education (MoE). Key multi-sector initiatives implemented so far include: reviewing school and literacy course curricula to effectively integrate practical nutrition skills; strengthening partnerships between health service providers (such as non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that support BPHS implementation) and stakeholders; advocating for the production, processing and storage of diverse foods; responding to local nutritional requirements; implementation of Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS); and documenting lessons learned to improve community-based nutrition promotion and inform future scale-up (NNPS, 2009).

Evolution of integrated management of acute malnutrition (IMAM) in Afghanistan

An international NGO launched the first programme for acute malnutrition management in Afghanistan in 1996, based on diverse guidelines and treatment protocols. After the establishment of the PND in 2003, with the support of UNICEF and WHO, the MoPH developed its own treatment guidelines adapted from WHO guidelines for management of acute malnutrition. In 2008, the PND introduced community-based therapeutic care (CTC), which was designed to address the limitations of previous nutrition programme models and maximise coverage and access to nutrition services. National nutrition guidelines and protocols were then revised accordingly. CTC was replaced two years later with community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM), which was integrated into the national health system. CMAM surpassed the limitations of CTC through full integration into all aspects of nutritional programming. The initiative included: education and nutrition outreach, management of MAM, outpatient treatment for children with SAM with a good appetite and without medical complications, and inpatient treatment for children with SAM and medical complications and/or no appetite.

Integration of acute malnutrition management into government health services system

Although the vision of CMAM was to integrate malnutrition management within the national health system, in practice it was implemented with support from the Nutrition Cluster as an emergency response mechanism. In order to address needs at all levels and develop a sustainable programme model, the MoPH decided to scale up management of acute malnutrition through the BPHS and EPHS and, in doing so, redirect its focus from ‘emergency’ to ‘development’. Pilots in Takhar, Badakhshan, Balkh and Herat provinces indicated the need for a comprehensive and integrated guideline with clear definitions to help health workers at different levels to detect and manage acute malnutrition properly. Therefore, in January 2014, MoPH endorsed the IMAM national guidelines developed by UNICEF and MoPH to fully implement this programme (MoPH/PND, 2014). The IMAM guidelines covered the detection of acute malnutrition at different levels of the health system; treatment of acute malnutrition through outpatient and inpatient departments; counselling of mothers and caretakers; and assessing/managing the main causes of malnutrition (including micronutrient deficiencies, suboptimal infant and young child feeding (IYCF) and poor home-based caring practices).

Since 2014, the IMAM approach has been implemented harmoniously throughout the country by government, public health institutions and BPHS and EPHS implementing partners and has enabled the scale-up and strengthening of nutrition programming. Sustainability of the programme has been ensured by support from regular development funds and resources. During emergencies, Nutrition Cluster resources have been mobilised and innovative approaches employed to increase coverage and improve the quality of services to reach those in additional need (MoPH, 2012).

IMAM scale-up plan and priority provinces

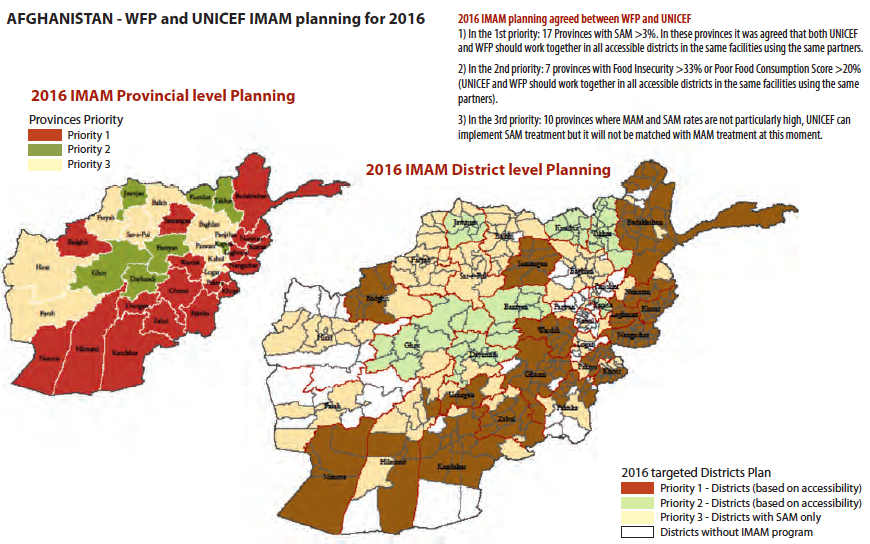

PND/MoPH and nutrition partners including UNICEF, WHO, World Food Programme (WFP) and the Nutrition Cluster develop an annual strategic action plan for IMAM scale-up at national level and in 34 priority provinces. In 2016, priorities were as follows (see also Figure 1):

- Priority 1: 17 provinces with SAM > 3 per cent to receive collaborative support of UNICEF and WFP in all accessible districts to provide SAM and MAM services concurrently through all accessible government health facilities.

- Priority 2: Seven provinces with food insecurity >(33 per cent) or poor food consumption score (>20 per cent) to receive collaborative support of UNICEF and WFP in all accessible districts to provide SAM and MAM services concurrently through all accessible government health facilities (same as priority one, but using different selection criteria).

- Priority 3: Ten provinces where MAM and SAM prevalence is not particularly high; UNICEF can implement SAM services only (no support required from WFP).

Figure 1: Priority provinces for IMAM scale-up in Afghanistan in 2016

In 2016, the IMAM programme aimed to reach 40 per cent of the SAM burden (171,770 SAM cases out of 423,520 national burden of SAM in children 0 to 59 months old) and 30 per cent of the MAM burden (254,743 MAM cases out of the national 764,021 MAM burden in children 6 to 59 months old). Actual numbers reached in 2016 were 201,470 SAM cases (above the target) and 199,018 MAM cases. PND/MoPH and nutrition partners will need to work together in all priority districts to fill service gaps in the future.

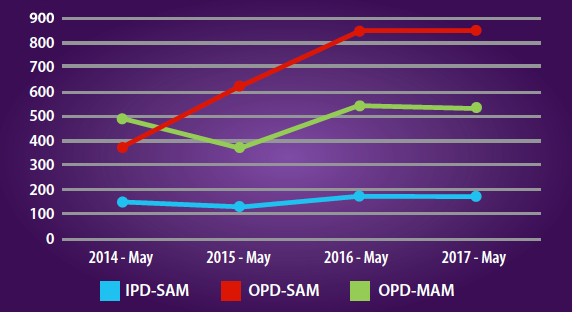

Analysis of coverage and performance of IMAM in Afghanistan

The IMAM programme was scaled up in all 34 priority provinces and nearly 78 per cent (313/399) of the districts had at least one component of the IMAM programme by 2017. Inpatient SAM (IPD-SAM) management services expanded to 63 per cent (92/147) of regional, provincial and districts hospitals (RH, PH & DH) or 178 health facilities by 2017. Outpatient SAM (OPD-SAM) management services were scaled up and operational in 1,028 sites in 34 provinces, covering 50 per cent per cent (855/1,999) of comprehensive, basic and sub-health centres (CHC, BHC and SHC) and 63 per cent (92/147) of RH, PH and DH. In terms of the outpatient management of MAM (OPD-MAM), services were scaled up and operational in 631 sites in 26 provinces, covering 30 per cent (563/1,836) of comprehensive, basic and sub-health centres and 47 per cent (68/147) of RH, PH and DH. In 2017 nearly 53 per cent (546/1028) of health facilities had both MAM and SAM complements of the IMAM operating together. Figure 2 shows the growth in IMAM services from 2014 to 2017.

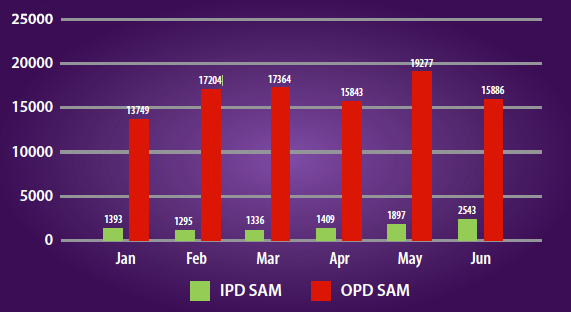

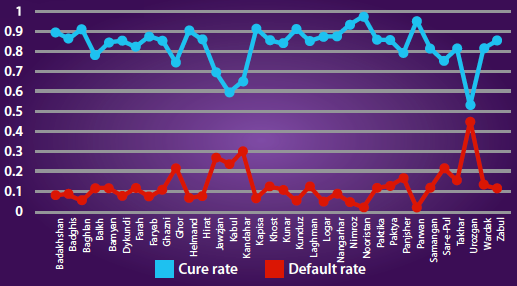

From January to June 2017, admissions of OPD-SAM ranged from 10,431 to 21,505 cases. Admissions of IPD-SAM were in the range of 1,020 to 1,897. The IMAM programme reporting rate ranged from 70 to 95 per cent for OPD-SAM and from 70 to 85 per cent for IPD-SAM services (see Figure 3). The overall SAM programme performance status was above Sphere standards during this same period (>75 per cent recovery rate); however, recovery and defaulter rates were below Sphere Standards for the management of SAM (i.e. <75 per cent recovered and >15 per cent defaulted) in six provinces (Badghis, Faryab, Kabul, Sarepul, Uruzgan and Wardak) for OPD/IPD SAM management services (see Figure 4).

Figure 2: Progress in scaling up IMAM sites in Afghanistan 2014 to 2017

Figure 3: Trend of newly admitted cases to SAM management services, Afghanistan, January to June 2017

Figure 4: Cure and defaulter rates by province, Afghanistan, January to June, 2017

Performance monitoring framework for IMAM in Afghanistan

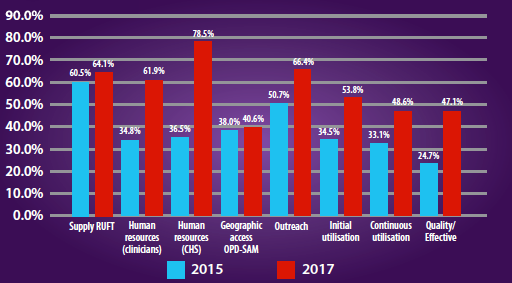

To scale up the IMAM programme efficiently in Afghanistan, it was crucial to identify and address the bottlenecks that hinder the access to and effective coverage of the programme and explore root causes and solutions to overcome them. Direct coverage assessment of the IMAM programme was initiated in late 2014; since then coverage assessments have been undertaken in targeted provinces. Bottleneck analysis (BNA) for improving access and enhancing coverage of IMAM was introduced in 2015 for performance monitoring. The results of the national SAM BNA analysis for 2015 and 2017 are shown in Figure 5. Similar analysis was done for each of the six regions (results available on request).

Figure 5: National SAM BNA results showing percentage score for potential bottlenecks for 2015 and 2017

Overall, comparison of the BNA analysis in 2015 and 2017 shows a significant improvement in the quality of SAM/ IMAM programming, particularly in the areas of human resources and quality/effective coverage of services. The highly significant improvement in human resources capacity can be explained by UNICEF and WHO countrywide trainings that took place following the 2015 BNA (explained in more detail below). However, many shortcomings remain, as follows.

The 2017 analysis revealed that only 64.1 per cent of OPD-SAM management sites did not encounter stockouts of ready-to-use therapeutic foods (RUTF) (far below the good performance threshold of ≥ 80 per cent); stock management training and inclusion of RUTF in the essential drugs list were identified as important solutions.

In terms of geographic access, only 40.6 per cent of BPHS health facilities were providing OPD-SAM management services at the time of assessment; better mapping for scale-up and monitoring of IMAM expansion are needed at provincial levels.

For outreach, 66.4 per cent of community health workers (CHWs) were trained on mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) screening; to improve on this, advocacy for more training is needed for CHWs in the new Community-based Nutrition Package (CBNP).1 Better performance monitoring is also required.

Only 53.8 per cent of SAM children were admitted for SAM treatment (initial utilisation); this low score is due to low prioritisation of the community component of IMAM, resulting in poor early case identification and referral; this will be strengthened in future through country-wide implementation of the CBNP.

Only 48.6 per cent of SAM children were admitted and continued treatment (continuous utilisation) (five per cent of cases discontinued treatment); to improve on this, nutrition staff must be hired in each health facility, nutrition recording tools must be simplified and more training must be given to CHWs. The recovery rate for children with SAM was 47.1 per cent (and defaulter rate over six per cent); the assessment identified supportive supervision and quality of recording and documentation as key areas for improvement to improve the quality of SAM management services.

Overall, the 2017 BNA revealed that IMAM programme implementation in Afghanistan improved, with positive changes in all areas since the 2015 assessment. However, a detailed operational plan for IMAM scale-up is needed based on these findings to ensure equitable scale-up with a clear road map towards its successful accomplishment, as well as the provision of the necessary support at provincial level. Findings of the BNA must be shared with all partners and donors to ensure incorporation of identified actions in national and provisional-level plans to reduce bottlenecks. Particular attention must be paid by the PND to addressing the gap in the community component of IMAM and to working with the Nutrition Cluster to explore how this component can be monitored. Similar attention must be paid by PND and UNICEF to improving quality supply-chain management to save costs and improve IMAM scale-up. Future BNAs can be improved through greater participation of nutrition partners and donors; integration of the BNA into routine IMAM monitoring with the inclusion of BNA indicators in the IMAM database; and the integration of other nutrition components into the BNA exercise.

Way forward

Tracking and monitoring progress

As identified in the NNPS for 2015-2020, addressing acute malnutrition is one of the MoPH/PND current priorities. Continued tracking of progress through IMAM monitoring is essential to meet the targets set in this plan and to be most effective, BNA monitoring must be integrated within it. Furthermore, the upgrading of the national nutrition reporting database from offline to online mode is in the final stages; this will support the timely submission of quality performance reports from the field-level and improve the feedback mechanism.

Nutrition Counsellors - new cadre to support skilled nutrition counselling at health facility level

Further strengthening the BPHS/EPHS system is the primary way to achieve sustainable IMAM services. UNICEF is advocating to the MoPH/PND to further strengthen the nutrition package to address all forms of malnutrition, within routine programming. As a result of such advocacy, nutrition counsellors are currently being hired for every health centre in 18 provinces, with primary responsibilities identified around maternal nutrition and IYCF counselling, growth monitoring, anthropometric assessment, nutrition education, facility tracking and monthly reporting.

Integration of nutrition supplies and capacity building into System Enhancement for Health Actions in Transition (SEHAT)

It is planned that nutrition supplies, equipment procurement and distributions, as well as capacity building, are carefully integrated into the SEHAT project (a fund, supported by the World Bank, US Agency for International Development (USAID) and European Union to support BPHS and PHS service delivery) and receive sustainable development funding. At the end of 2017, UNICEF is advocating to include RUTF supplies for routine SAM treatment without complications under this project, while additional emergency-related supplies will continue to be procured through emergency funding. Other supplies procured by UNICEF and WFP are still not included in the SEHAT.

Comprehensive capacity building approach

The 2015, the BNA revealed human resources to be a key bottleneck for the delivery of quality IMAM services at scale. In response, UNICEF has provided support to the government and implementing NGOs through trainings on nutrition standard operating procedures (SOP), with a significant focus on IMAM, and by partnering with WHO to provide trainings on inpatient management of acute malnutrition across the country. This explains the major improvement in human resource capacity revealed in the 2017 BNA.

Further improvements are expected as a result of the introduction of the CBNP to strength the community component of nutrition interventions including IMAM, and the revision of the IMAM package (including the operational guidelines and training package) by the MoPH with the technical support of UNICEF. In addition, supportive monitoring and supervision has been strengthened through the use of MoPH staff at different levels, UNICEF field office staff, and third-party monitors (TPMs), as well as a network of nutrition “extenders” (one per province) who triangulate data received from TPMs; data is used to support improvements in programme development and planning, implementation, monitoring and programme management.

Scale up to high burden, low coverage provinces

In 2016 UNICEF supported the government to scale up SAM treatment coverage in three of the priority one provinces with high burdens of SAM: Wardak, with SAM burden of 26,271 children and only coverage of 3.1 per cent (12 OPD-SAM sites), Paktia with SAM burden of 25,505 children and coverage of 18.6 per cent (25 OPD-SAM sites) and Lagman with SAM burden of 11,411 children and coverage of 27.3 per cent (26 OPD-SAM sites). Activities have included the establishment of additional OPD-SAM sites, capacity building at district and facility levels, implementation of “days for active screening only” by CHWs, performance-based incentives for CHWs and improvements in screening and referrals (including use of a new tracking tool by CHWs). The results from this pilot scale-up will be used to inform further scaling up of SAM treatment in high burden-low coverage areas throughout the country. MoPH/PND and UNICEF are currently supporting BPHS partners working in these three provinces to implement the scale-up plan. In addition, and based on the BNA analysis, a discussion has started on the scaling up of OPD-SAM in three more provinces (Parwan, Kapisa, and Panjsher) through similar activities.

Scale-up of IMAM through mobile health and nutrition teams

IMAM services in Afghanistan are hampered by lack of access to remote health facilities. In order to improve coverage of IMAM services UNICEF and the Nutrition Cluster supported government to develop guidelines for the integration of nutrition into mobile health teams in order to improve access to IMAM services in hard to reach areas. With the support of UNICEF and nutrition cluster, four integrated mobile health and nutrition teams established in four districts of Faryab province and eight integrated teams established in eight districts of Kandahar provinces.

Conclusions

The MoPH has done an excellent job of developing an essential nutrition policy, strategies and guidelines according to guiding principles that promote comprehensive, equitable and sustainable care for those in need, based on the global evidence base. Evidence shows that IMAM services have gradually scaled up and improved in Afghanistan. In total, 236,121 acutely malnourished children were provided with life-saving treatment services in 2014, followed by 315,890 in 2015, 400,488 in 2016 and 457,000 in 2017. Significant improvements can be seen in the quality of IMAM services implemented and in scale-up and integration into the routine health system. More supportive supervision and mentoring are needed in the health system to maintain quality and to complete the integration of RUTF in the MoPH essential drug list. A formative evaluation of the IMAM approach is also needed to gather evidence on results, lessons learned and good practices and shared widely to inform future policy and programming to improve the treatment of acute malnutrition. Efforts are also needed to further strengthen the health system in Afghanistan so that acute malnutrition can be addressed as part of the routine health service, with capacity to scale up in response to emergencies. This must become embedded in the contingency planning of development strategies, policies and practices.

For more information, contact Ahmad Nawid Qarizada.

Endnotes

1The Community-based Nutrition Package (CBNP) is a practical, comprehensive, minimum service delivered at community level as an adjunct to health facility services that aims to provide a robust delivery platform for sustainable, high-impact nutrition interventions with the BPHS package.

References

Afghanistan Food Security and Nutrition Agenda (AFSeN), 2012.

Afghanistan National Nutrition Survey (NNS), 2013.

Basic Package of Health Services, 2010.

Bottleneck Analysis (BNA), 2015 and 2017.

Demographic Health Survey (DHS) for Afghanistan, 2015.

Essential Package of Hospital Services, 2005.

FEWSNET, 2017.

MoPH Strategy 2011 to 2015 and 2016 to 2020.

National Nutrition Database 2014 to 2017.

National Nutrition Strategy 2009 to 2013 and 2015 to 2020.

SMART Surveys, 2017.