Improving nutrition surveys: New developments and changes at UNHCR

By Timo Luege, Caroline Wilkinson and Maeve de France

Timo Luege is an independent, humanitarian communications and advocacy consultant based in Berlin, Germany. Timo has experience working for non-governmental organisations (NGOs), United Nations (UN) and the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement both at headquarters and in the field. Timo works regularly for CartONG1.

Caroline Wilkinson is the Senior Nutrition Officer for the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) and was fully involved in the development of the SENS and the introduction of mobile data collection in UNHCR SENS surveys. She previously worked for 14 years with Action Contre la Faim (ACF) in several countries and headquarters in Paris.

Maeve de France has been an Information Management Project Manager for CartONG for three years. Prior to this she worked for five years in the private sector as a geographical information management project manager.

Over the last two years, the number of people facing crisis-level food insecurity has grown from 80 million to 135 million (FSIN, 2017). At the same time, many humanitarian organisations providing food and nutrition services (in kind or cash-based) are struggling with ever-increasing funding gaps, which have repeatedly forced them to cut back assistance.

Given that aid organisations need to reach more people on decreased budgets, it is ever more important that the money is spent as efficiently as possible. Surveys and assessments are an essential part of ensuring that sparse funds go to the most urgent crises and that in each crisis the most vulnerable are prioritised.

Box 1: Summary of SENS report contents

A SENS report includes information on the following data:

- Levels of malnutrition and key health indicators in children

- Levels of anaemia in children and women

- Feeding practices of infants and young children

- Access to food at the household level

- Access to safe drinking water, toilets and hygiene practices at the household level

- Access to and use of mosquito nets at the household level

UNHCR’s Standardised Expanded Nutrition Survey (SENS), described in Box 1, is based on the Standardised Monitoring and Assessment of Relief and Transitions (SMART) methodology and provides valuable data to identify urgent needs, and changes in needs, in refugee contexts. Over the last five years the number of SENS surveys has risen from 63 in 2012 to 109 in 2016.

But every survey is only as good as the data it captures. Since 2011 UNHCR and its implementing partner for mobile data collection (MDC), CartONG, have been using MDC to increase data quality. As part of that collaboration, the percentage of SENS surveys that use MDC has grown from 32 per cent in 2013 to 95 per cent in 2016.

Most recently, UNHCR and CartONG have focused on three areas to further increase the quality of SENS for all humanitarian organisations that are using it.

1. Making SENS trainings less burdensome

Gathering anthropometric data is labour-intensive. A typical survey team consists of four to six people who must carry scales and height boards, take measurements and record data. There are many opportunities for mistakes to creep in, particularly when getting information from children or infants. To reduce the likelihood of data-capture errors, UNHCR and partners train all enumerators rigorously. This involves a five-day training that includes, among other things, what is known as the standardisation test. Conducting a standardisation test for anthropometric measures is a fundamental part of the training, since it allows objective assessment of the precision and accuracy of the measurements made by the enumerators, their strengths and weaknesses.

During the standardisation test, up to 20 enumerators measure ten children, usually aged between 18 and 59 months. Each measurement is repeated twice by each enumerator for each child, with a time interval between both rounds of measurements. Collecting all measurements takes between half a day and a full day, which is exhausting and tiring for both the survey team and the children. At the end of the day the measurements are compared with reference data collected by the trainer and that information is used to determine which enumerators are capable of which role, or whether some enumerators need additional training prior to the start of the survey. Until now, the facilitator has manually entered the captured data into a spreadsheet at the end of the day, a process that took a considerable amount of time and was a potential source of data input errors.

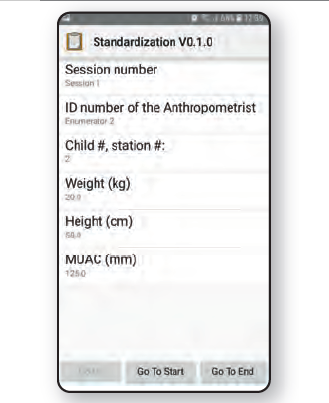

While UNHCR has used smartphones to capture SENS data for many years, prior to 2016 they had not been used for the standardisation tests that are part of the enumerators’ training. The main advantages of using smartphones for the standardisation tests are that data entry is much faster; there are fewer data entry errors; and it is harder for trainees to “cheat” during the training; for example, by manually copying data that has been captured earlier (see Figure 1). While this process still has some technical challenges that need to be resolved, the technical implementation has already improved significantly from Jordan in 2016 to Burundi in 2017. UNHCR and CartONG are confident that the remaining technical issues can be ironed out in 2018 and that full support for MBC for the SENS survey standardisation tests can be made available soon.

Figure 1: Screenshot of a standardisation test using a smartphone

2. Monitoring and verifying the sampling strategy through geolocation

A typical SENS survey takes between 30 and 45 minutes per household, so most teams can only talk to between 12 and 17 families per day. Particularly in large refugee camps, this means relying on random sampling to ensure that the data are representative. In some cases, with multiple teams working in different parts of a camp or town, it can be difficult for the survey manager and supervisors to monitor progress of the teams and to ensure that the sampling methodology is being followed by all team members. By setting the smartphones to collect global positioning system (GPS) data, together with the survey data, supervisors can see precisely which houses were visited and whether this was in line with the agreed sampling strategy. In addition, supervisors can see whether teams have taken unusually long or were uncharacteristically fast when collecting data in specific locations, either of which might indicate data quality issues.

3. Putting SENS on the map

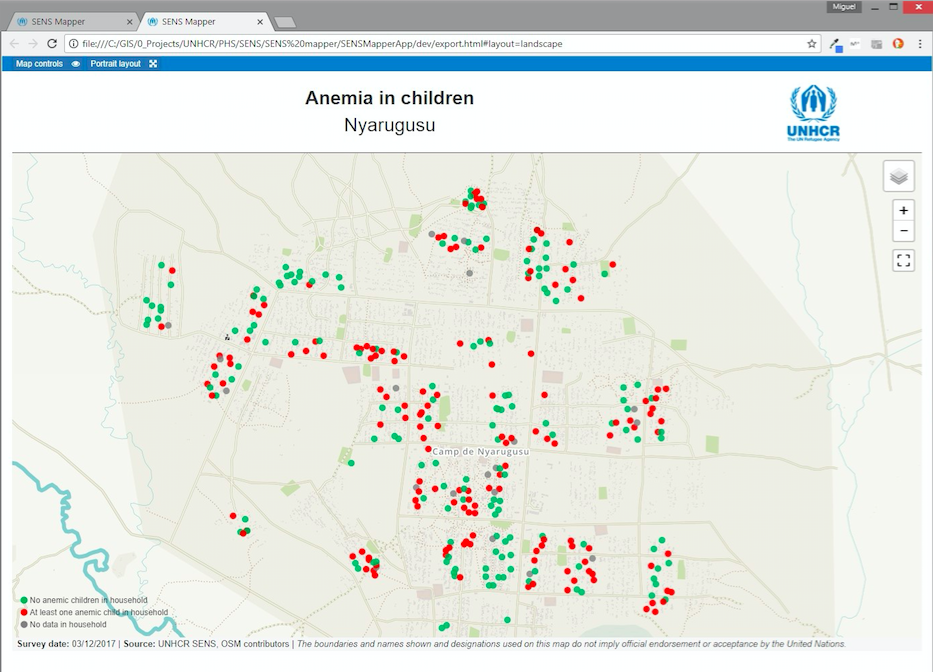

While most nutrition experts feel very comfortable reading long tables with rows of data, this information is not always easy to convey to donors or to use in reports for non-experts. Maps can help make technical data more easily consumable for a wider audience. The new SENS mapper is a free, browser-based data viewer that can quickly show the distribution of SENS data on a map, including indicators for nutrition, safe drinking water and mosquito net coverage and where there are gaps.

While it is generally accepted that malnutrition is not geographically clustered, these maps can nevertheless be useful advocacy tools. Possible examples include showing that malnutrition levels are very different for new arrivals compared to refugees who have had access to food and services in a camp over a longer period. Similarly, a map could highlight areas of a camp where refugees have insecticide-treated nets but are not using them.

The free SENS mapper has just been published and can be accessed through the UNHCR map portal (http://maps.unhcr.org/apps/mdc_mapper/sens/index.html). The SENS mapper can easily create visualisations like those displayed in Figure 1 if SENS data is captured with smartphones.

Figure 2: Screenshot of the free SENS mapper

Red dots represent households with at least one anaemic child; green dots represent households with no anaemic children.

Red dots represent households with at least one anaemic child; green dots represent households with no anaemic children.

For more information, contact: hqphn@unhcr.org.

Endnotes

1CartONG, a long-time partner of UNHCR, is a French non-profit organisation committed to furthering the use of mapping, mobile data collection and information management in emergency relief and development programmes.

References

FSIN 2017. Food Security Information Network (FSIN) Global report on Food Crises 2017. www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/newsroom/docs/20170328_Full Report_Global Report on Food Crises_v1.pdf Retrieved: 4 Dec 2017.