C-MAMI tool evaluation: Learnings from Bangladesh and Ethiopia

By Sarah Butler, Nicki Connell and Hatty Barthorp

Sarah Butler is the Director of Emergency Nutrition at Save the Children, USA. She has more than ten years’ experience in nutrition and has been leading the team since SC began implementation research into C-MAMI in 2013.

Nicki Connell is the Eleanor Crook Foundation’s Nutrition Technical Director. Nicki previously was an Emergency Nutrition Advisor for Save the Children and served as Project Manager for this work. Nicki has ten years’ experience in emergency nutrition, with a large proportion of her work focused on the management of at-risk mothers and infants (MAMI).

Hatty Barthorp is the Global Nutrition Advisor at GOAL. She has more than 15 years’ experience in emergency and development nutrition programming and has been advising the GOAL Ethiopia team since GOAL began implementation of C-MAMI in 2016.

Save the Children and GOAL would like to thank the following members of the Evaluation Team: Sinead O’Mahony, GOAL Ireland; Marie McGrath, ENN; Jay Berkley, KEMRI/Wellcome Trust; and Marko Kerac, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The evaluation was led by Nutrition Policy and Practice consultants Mary Lung’aho and Maryanne Stone-Jimenez and field work was conducted by Louise Tina Day.

Location: Bangladesh and Ethiopia

What we know: Community-based management of uncomplicated severe acute malnutrition in infants under six months is recommended by WHO; the community-based management of at-risk mothers and infants less than six months old (C-MAMI) tool was developed to help put this into practice.

What this article adds: An evaluation was carried out of a GOAL pilot C-MAMI project in two refugee camps in Ethiopia and a Save the Children pilot C-MAMI project in Bangladesh to test the C-MAMI approach and C-MAMI tool (Version 1). An inter-agency evaluation team conducted key informant interviews and focus group discussions and employed questionnaires, observations of assessment and management, case scenarios and a quiz for tool users. Overall findings were positive: respondents reported that infants received quicker and better treatment than previous standard care (inpatient referral). Areas for development include strengthening mother support and clarity on linkages with infant and young child feeding (IYCF) programming. The C-MAMI tool was found to have provided a necessary, comprehensive framework; areas for improvement, such as admission and discharge criteria, were identified and have informed Version 2. To support implementation, development of standard operating procedures, monitoring tools and sensitisation is needed. To aid scale-up, more research is needed to test this approach.

Background

In 2013 the World Health Organization (WHO) released updated guidance for the identification and management of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) in infants under six months of age (U6m), including outpatient management of uncomplicated cases (WHO, 2013). To operationalise this, in 2015 the MAMI Special Interest Group (an ENN-led collaboration of researchers, practitioners and experts) developed Version 1.0 of the Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition in Infants under six months (C-MAMI) tool. This was based on risk factors identified from studies in Bangladesh, which were led by Save the Children (Islam et al, 2018) and in Malawi, which were led by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). In 2016, LSHTM led a project to adapt and test the C-MAMI tool and developed a simplified, easy-to-use checklist and supporting documentation to operationalise the C-MAMI package (www.ennonline.net/ourwork/mami). GOAL and Save the Children initiated C-MAMI pilots to test the approach and assist in the revision of these tools.

In February 2016 GOAL began integrating C-MAMI into nutrition programming in two refugee camps in Gambella region, Ethiopia. In June 2017 Save the Children began piloting C-MAMI in government health services in the disaster-prone area of Barisal, Bangladesh, as part of an implementation research project. In November 2017 Save the Children funded an evaluation of the C-MAMI tool Version 1.0 to capture lessons learned and inform an update of the tool. To add greater value to the evaluation, GOAL funded additional data collection from Ethiopia. This article summarises the methodology, findings and recommendations of that evaluation.

Study location and methodology

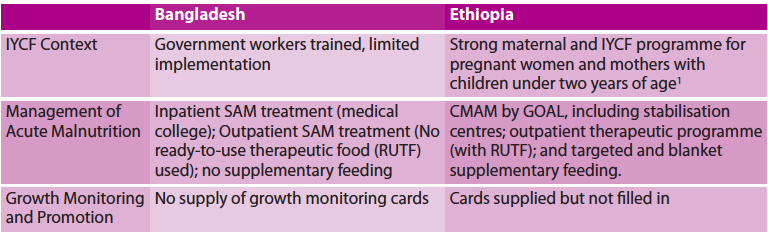

Save the Children’s pilot project in Barisal Sadar, Bangladesh, was implemented by C-MAMI counsellors with either a nutrition or agriculture background who received a seven-day classroom training. GOAL’s pilot project in the refugee camps of Terkidi and Kule in Gambella, Ethiopia, relied on C-MAMI nurses with either infant and young child feeding (IYCF) and/or community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) experience, who received 0.5-5 days of training through a mix of classroom and on-the-job orientation. Table 1 provides a short description of nutrition programming in the implementation sites.

Table 1: Description of implementation sites

The evaluation was designed and carried out by an inter-agency evaluation team (see acknowledgments) using a mixed-methods approach to obtain information on user experiences with the C-MAMI programme and tool. The fieldwork consultant worked with in-country focal points and visited both field locations for seven days each in November and December 2017. Data were collected through key informant interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs), questionnaires, observation of mother-infant assessments and management, case scenarios and an ‘open book’ quiz for trained tool users. The evaluation team selected 48 respondents (32 Bangladeshi and 16 Ethiopian). These included enrolled and discharged beneficiaries of the programme, trained C-MAMI tool users, community outreach workers, programme supervisors and context experts, including non-governmental organisation (NGO) and government staff and stakeholders with local programming expertise.

Evaluation findings

C-MAMI programme

Overall, respondents expressed appreciation of the C-MAMI programme. Senior managers in both locations agreed that the programme addresses a need that was not necessarily perceived previously. “There are less babies under six months admitted (to Stabilisation Centre) with complications because now C-MAMI prevents them getting so severe.” (SC nurse: Ethiopia). There was agreement in both Bangladesh and Ethiopia that infants treated through C-MAMI recover more quickly than older children treated in CMAM (IYCF counsellor, Ethiopia; Supervisor / Manager, Ethiopia and Bangladesh).

At the same time, progress in terms of support for mothers’ recuperation is needed. Respondents noted that mothers were more motivated to adhere to treatment for their infants than themselves. One respondent in Ethiopia commented that C-MAMI is perceived to be only for infants; not for mothers. In general, respondents stated that the support for mothers (nutritional and non-nutritional) needs to be strengthened. The quiz identified more misclassified cases of mothers than infants, underscoring the need to improve guidance on this section of the tool.

A consistent theme raised by respondents was the relationship between C-MAMI and IYCF programming. Many community members, outreach workers and programmers expressed confusion about the distinction between the two, saying that they were unclear as to which infants were eligible for screening and management in one programme versus the other. The quiz reinforced this finding with C-MAMI tool users, who were sometimes unclear when to assign a case among the three case management options (referral to a facility, C-MAMI enrolment or linkage with IYCF support). However, misidentification of programme enrolment does not equate with mismanagement (there is intentional overlap between these programmes), although it does highlight that distinctions, connections and synergies need to be resolved between C-MAMI and IYCF programming.

Even with the need to clarify the roles of the two programmes, respondents underscored the importance of strong relationships between IYCF and C-MAMI programmes. “The focus should be on IYCF; IYCF is for all” – with C-MAMI added alongside IYCF programming to ensure ‘at-risk’ mothers and infants receive appropriate care. Some implementation staff reported that an advantage of C-MAMI is the increased likelihood that IYCF concerns will be addressed. “IYCF is meant to be integrated into many service points. Because IYCF is everyone’s responsibility, no one is accountable. Some doctors and sisters [nurses] are neglecting this type of task (IYCF counselling). Every provider should be oriented to the C-MAMI programme.” (Programme Manager, Bangladesh). Implementation staff responses varied when asked whether C-MAMI is best suited for incorporation in a health or nutrition programme. This is likely a reflection that breastfeeding counselling is included in both or either sectors in various settings.

C-MAMI tool

A focus of the evaluation was to gather feedback on the C-MAMI tool Version 1.0 to inform revisions. In general, respondents in both settings described the tool as “useful”, “filling a gap”, “comprehensive”, “covers everything that the health worker needs to know to manage the infant U6m” and “user-friendly”. In-depth feedback on the tool was provided by respondents and through observations of use. This feedback was incorporated in the creation of C-MAMI tool Version 2.0 (see news article in this issue).

A major area for C-MAMI improvement is related to admission and discharge criteria. Respondents discussed the need to revisit anthropometric measures and cut-offs for admission (mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) cut-offs and use of weight-for-age (WFA)) and a need to define terms for infant assessment (‘severe’ vs ‘moderate’ weight loss; ‘sharp’ and ‘moderate’ drops across growth-chart centile lines). Respondents also noted the lack of clear discharge criteria (anthropometric measurements, minimum/maximum lengths of stay) and procedures (referral to additional nutrition services, follow-up and monitoring of outcomes).

Respondents also commented on the monitoring tools associated with the C-MAMI tool. Currently there are no standardised reporting and recording formats for C-MAMI. In Ethiopia, all forms are paper-based, while Save the Children’s programme in Bangladesh uses both a tablet-based C-MAMI app and paper forms for assessment, classification and programme monitoring. In all locations respondents requested data collection processes and tools to be streamlined and duplications eliminated.

Feasibility of scale-up

In relation to the feasibility of scale-up and sustainability, stakeholders in both settings requested more evidence to support the C-MAMI approach, including the underlying need and programme objectives, component interventions and a monitoring strategy. Several senior managers mentioned that confusion had been caused by the lack of standard operating procedures, protocols, procedural manuals and standardised operational tools (i.e. training curricula and reporting formats). In both contexts, senior-level respondents emphasised the need to pilot C-MAMI with government health workers (described by one respondent as the real target users). Respondents also indicated that sensitisation is needed from national to community levels to increase the understanding and buy-in for C-MAMI.

Recommendations

The following key recommendations emerged from the evaluation, some of which were incorporated into C-MAMI tool Version 2.0:

- Create a simpler, user-friendly C-MAMI tool; unify and streamline triage, assessment, classification and management of the infant-mother pair.

- Develop guidance on the use of the C-MAMI tool; include greater guidance on counselling and describe changes from Version 1.0 to 2.0.

- Clarify admission and discharge criteria, as well as follow-up procedures once discharged.

- Strengthen guidance on maternal depression/anxiety/distress.

- Develop a standardised C-MAMI training curriculum.

- Simplify and standardise monitoring guidance, including a minimum set of monitoring indicators.

- Conduct further research on the burden of malnutrition in U6m and key operational questions (anthropometric thresholds and non-nutrition issues, such as maternal depression and adolescent pregnancy); advocate for routine data collection on infants U6m in national and sub-national prevalence surveys.

- Consider an advocacy and sensitisation campaign to mobilise support for C-MAMI.

Partners are now seeking to pilot the revised tool to gather user feedback for continued improvement.

For more information, please contact Sarah Butler.

Endnotes

1The programme is delivered in a ‘1,000 days room’: a dedicated, quiet and comfortable area within the CMAM programme; mothers can relax to feed, discuss concerns and be supported as a group or individually, through counselling and practical support.

1Islam MM, Arafat Y, Connell N, Mothabbir G, McGrath M, Berkley JA, Ahmed T, Kerac M. (2018). Severe malnutrition in infants aged <6months – Outcomes and risk factors in Bangladesh: A prospective cohort study. Matern Child Nutr. 2018; e12642. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12642

References

WHO. Guidelines: Updates on the management of severe acute malnutrition in infants and children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.