Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) in Protracted Crisis: The South Sudan Civil Society Alliance (CSA) experience

By Mercy Laker, Dr Soma Emmanuel and Joseph Scott

Mercy Laker is Assistant Country Director for CARE South Sudan. Prior to this she served as the Health and Nutrition Coordinator for CARE, when she played a central role in activating the South Sudan SUN Civil Society Alliance. Mercy is a public health nutritionist with 14 years’ hands-on experience in nutrition programming in both emergency and development contexts at various levels.

Dr Soma Emmanuel has worked with CARE South Sudan since 2017 as Country Health Manager. His contributions in coordinating the implementation of SUN Civil Society Alliance activities among member agencies have been crucial in ensuring that the Alliance remains coherent

Joseph Scott is a Communication and Policy Coordinator for CARE South Sudan. He is a communication specialist with ten years’ experience delivering communications and advocacy strategies for donors, the United Nations, leading non-governmental organisations and development contractors.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and involvement of the Ministry of Health South Sudan, UNICEF South Sudan, World Food Programme South Sudan, the South Sudan SUN CSA and the SUN CSA Global Secretariat.

Location: South Sudan

What we know: Nutrition programming in South Sudan is dominated by treatment of acute malnutrition.

What this article adds: South Sudan officially joined the global Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement in 2013; armed conflict delayed launch until 2016. In 2017 CARE mobilised civil society organisations (CSOs) to form the South Sudan SUN Civil Society Alliance (SUN CSA). It aimed to promote integration of sustainable nutrition-sensitive interventions within the protracted crisis, amplify CSO voices and raise the profile of nutrition among multiple stakeholders. Immediate activities included awareness raising and development of a Terms of Reference and structure. It currently comprises 35 members, with sub-national expansion of coordination, prioritising high-burden counties. The nutrition cluster has played a pivotal role in bringing civil society actors to the table. Challenges include lack of a nutrition policy framework and infrastructure with which to align long-term, nutrition-sensitive interventions; programmes are typically guided by short-term humanitarian response plans with short funding cycles. The South Sudan SUN CSA remains at inception phase, mainly due to limited financial and human resources, and is dependent on individual rather than agency-level commitment. The Nutrition Cluster has helped create a favorable perception of multi-sector, nutrition-sensitive interventions in an emergency context. Next steps include advocacy for development of a South Sudan Nutrition Action plan and M&E plan, scale-up of the SN SCA strategy, strengthening gender mainstreaming in nutrition interventions, and joint resource mobilisation. Moving towards preventive programming is possible in proacted crisis, but requires deliberate action.

Background

Nutrition programming in South Sudan is strongly skewed towards treatment of acute malnutrition. Donors are largely unwilling to fund interventions to prevent malnutrition through multi-sector, nutrition-sensitive programming due in large measure to the time required to achieve results. South Sudan officially joined the global Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement in 2013 following a letter of commitment from the Government. However, due to armed conflict that broke out in December 2013, the SUN Movement was not launched in South Sudan until 2016. After its launch, the United Nations SUN Network and Steering Committee were formed. The Steering Committee at the time consisted of representation from the World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF and the Ministry of Health (MoH). The Under Secretary of the MoH acts as the Country convenor and SUN Focal Point. At the time, most of the emergency-focused civil society organisations (CSOs) in South Sudan had little connection or knowledge of the SUN Movement.

The causes of malnutrition in South Sudan are broad and complex. The SUN Movement provides a suitable platform for the promotion of a multi-sector and multi-disciplinary approach to address undernutrition, involving nutrition actors from a wide range of fields and not just those focused on the community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM). The eventual launch of SUN in South Sudan occurred at the same time as the inter-cluster working group (ICWG) was promoting an integrated package of interventions, including Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), Health, Nutrition and Food Security, and Livelihoods (FSL), jointly developed by the respective Clusters. Recognising the goodwill of the Government and UN towards the SUN Movement and the strength of South Sudan’s civil society, in October 2017, following the approval of the Government of South Sudan and the South Sudan SUN steering committee, CARE began mobilising CSOs to form the South Sudan SUN Civil Society Alliance (SUN CSA).

The CSA formation process

CARE reached out to the Government through a letter notifying the MoH of the intention to form and lead the SUN CSA. CARE’s motivation was to arouse interest among CSOs in South Sudan to promote integration of nutrition-sensitive interventions within the ongoing protracted crisis for sustainability. The SUN CSA would further provide a suitable platform to amalgamate and amplify CSO voices alongside the UN and government networks and profile nutrition as everybody’s business, rallying commitment from government, donors, academia, private sector and other CSOs to the cause. CARE was invited to make a presentation before the SUN Steering Committee to gain its approval, alongside two other organisations who had also expressed interest in leading the Alliance. After the presentations the Committee endorsed CARE’s leadership of the Alliance. Save the Children was assigned to co-Chair and Christian Aid became Secretary to the Alliance, together making up the South Sudan SUN CSA Secretariat. CARE then developed an annual work plan and budget and outlined the intention for SUN CSA. The activities and strategies were to be jointly defined and co-funded by members of the alliance to promote ownership and sustainability.

Recognising the need for endorsement from a broader range of agencies, the SUN CSA Secretariat began mobilising other non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to register. Several other agencies subsequently joined the SUN CSA and these agencies (World Vision International, Catholic Relief Services (CRS) South Sudan, Women’s Network for Development and Nile Hope), together with the Secretariat, formed the South Sudan SUN Executive Committee (EC). This formally set in motion the activities of the South Sudan SUN CSA in November 2017. The EC proceeded to adopt Terms of Reference (ToR) that set out the roles of the Chair, co-Chair and Secretary, common purpose and collective responsibilities of the secretariat, EC and SUN CSA membership. The SUN CSA TOR set out to achieve a South Sudan free of hunger and malnutrition by 2030. The EC capped the Secretariat term at two years, after which SUN CSA members would select new leadership by vote at an annual general meeting.

Led by CARE, the EC embarked on a process of awareness-raising of the SUN CSA, primarily by making presentations at Health, FSL and Nutrition Cluster meetings and circulating registration forms. It was a requirement that the registration form be signed at the highest level within each agency. Thereafter, organisations were requested to submit their profiles to the Secretariat for filing. These documents were also shared with the MoH.

The SUN CSA Secretariat met weekly during the set-up process to develop the structure and TOR and assess registrations for membership, which was also shared with wider members. A three-day workshop was held between 29 and 31 January 2018 to develop a strategic plan for 2018-2020, including annual activities and budgets. The overall strategic goal was to increase government, donor and CSO commitment to prioritise nutrition as a core sector and as an indicator of development. Specific objectives of the strategy are: (1) Partnership with academia nutrition research, policy influence and advocacy with South Sudan legislators, planning authority and donor community; (2) Nutrition awareness-creation targeting communities, private sector and legislators; and (3) Capacity-building of government and civil society, including grass root organisations.

In December 2017 CARE engaged a temporary SUN Coordinator for two months to kickstart activities. The funding for this came from a supplementary grant from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA), used as last resort financing by CARE.

South Sudan SUN CSA current role and activities

The SUN CSA is currently comprised of 35 members, including international and national CSOs, and continues to be governed by the same Secretariat and EC, as described above. The SUN CSA has begun to act on its strategy through co-funded advocacy and awareness-creation activities, including one public lecture conducted in partnership with Juba University under the theme Integrating Nutrition into Agriculture Value Chains. This event marked an important step in engaging academia in South Sudan. Similar activities have been planned on a quarterly basis.

The SUN CSA continues to grow its membership and establish coordination mechanisms at the sub-national level, with a focus on high-burden counties, including Warrap, Unity State, Jonglei and Eastern Equatorial State. The SUN CSA has an action plan to cascade SUN activities beyond national level through existing members. For example, CARE will support sub-national scale-up of nutrition in Unity State and Action Against Hunger and World Vision will support scale-up in Warrap, among others. Activities will include awareness-raising of integrated, nutrition-sensitive programming, research and capacity-building of community groups to advocate for funding, and inclusion of nutrition-sensitive interventions using CARE’s community score card.

The SUN CSA’s prominent role in scaling up nutrition was highlighted by its participation in the 2017 SUN global gathering in Abidjan, East Africa. SUN CSA members, alongside the MoH, Ministry of Agriculture, UNICEF and WFP, profiled South Sudan’s successes and challenges in the integration of nutrition-sensitive programming into emergency response, showcasing various publications from South Sudan mostly developed by UN, CSOs and individuals as well as the South Sudan CMAM guidelines and the Maternal Infant and Young Child Nutrition guidelines. At the meeting the South Sudan team also participated in panel discussions on SUN in fragile contexts. The CSA took home many lessons from the meeting. Notable lessons were the use of nutrition champions in Tanzania, engaging parliamentarians in Zambia and the call to stop ‘preaching to the choir’ and reach out to non-nutritionists.

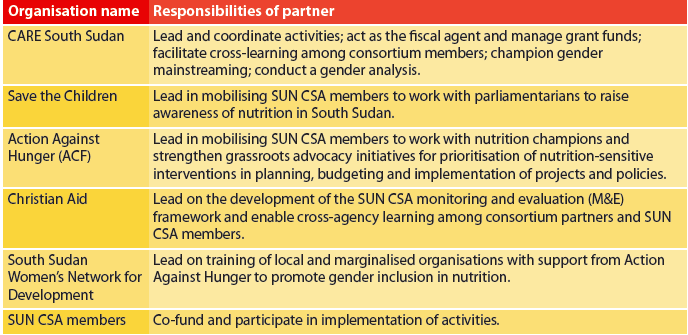

Members of the CSA (CARE, Save the Children, Action Against Hunger, Christian Aid and Women’s Network for Development) recently formed a consortium to submit a funding proposal to the SUN pooled fund, which was eventually funded by the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS). In the consortium each member is assigned an activity to be implemented through the entire SUN CSA membership, as described in Table 1.

Table 1: Rose and responsibilities of partners in the SUN CSA Consortium

Challenges

The conflict that broke out in 2013 denied the Government of South Sudan the opportunity to implement the country’s five-year development plan. As a result, SUN lacks a nutrition policy framework and infrastructure with which to align long-term, nutrition-sensitive interventions. The Republic of South Sudan does not have a multi-sector action plan or a related M&E framework to guide sector-wide implementation and monitoring and the roles of other would-be critical players, such as the private sector, academia and donors in SUN, remain undefined. This limits opportunities for nutrition financing and interventions such as micronutrient fortification, usually led by the private sector. Programmes are mostly guided by the Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP), which follows one-year planning cycles to mitigate risks for implementing partners and donors. Although a few donors, such as the Swiss Development Cooperation, Dutch Relief Alliance and Global Affairs Canada, fund longer-term resilience activities, many prefer short funding cycles aligned to the HRP.

The role of the Nutrition Cluster and technical working groups (TWGs) in managing malnutrition at country level has been critical. The Cluster’s mandate, however, remains narrowly focused on treatment, with limited integration of nutrition-sensitive interventions. The ICWG has recently developed a minimum training and delivery package for integration across Nutrition, Health, WASH and FSL Clusters. However, the impact of such efforts remains to be seen as the work of these Clusters does not always overlap geographically and, due to resource limitations, prioritisation inevitably occurs, leading to trade-offs between integrated programming and treatment of wasting.

A further challenge is the SUN CSA’s inability to operate independently from the Government in South Sudan. The SUN CSA was, for instance, required to seek permission from the Government to form and afterwards was obliged to submit all minutes of meetings, TORs and strategy for MoH approval.

Aside from a limited number of women’s networks and organisations, there is still limited gender integration/mainstreaming and engagement of women and women-led groups in the implementation of nutrition-sensitive interventions, even though women are central to nutrition at household level.

The progress of the SUN movement in South Sudan has remained intermittent and mostly driven by external consultants. These one-off consultancy assignments have not been owned and coordinated by civil society actors, which limits the sustainability of the initiative.

Despite the progress made, the SUN CSA is still at an inception phase and faces several challenges in establishing a platform and membership at the sub-national level, engaging multi-sector actors and scaling up its activities nationally. This is mainly due to limited financial and human resources. Even where there is commitment to co-fund some of the activities prioritised in the SUN CSA strategy, individual organisations have reported little-to-no funding for nutrition-sensitive interventions due to the emergency nature of their response plans. Nutrition activities in most organisations are currently funded through the South Sudan Humanitarian Fund (SSHF), UNICEF or WFP agreements in 12-month cycles. National NGOs find it particularly challenging to complement these funds, although joining networks such as the SUN CSA increases their chances of diversifying their funding base.

So far, SUN CSA activities have been concentrated at national level. At the state and sub-national level, scaling up nutrition interventions have not yet taken root, despite the fact that most of the 1,000 plus national and grassroots organisations in South Sudan have no representation at national level. This leaves gaps when it comes to implementing nutrition-sensitive interventions agreed upon in response plans.

Finally, there has been inadequate advocacy to policy-makers – particularly parliamentarians – to prioritise legislation and financing for nutrition. The food and nutrition policy, for instance, is still to be passed in Parliament; hence, there is no legal framework for nutrition activities in the country.

Enablers

The SUN CSA membership consists of leading nutrition implementing agencies in South Sudan. CARE, for instance, has a global SUN task force, which has provided both technical and financial resources for the South Sudan SUN CSA. The CARE SUN task force support included financing representation at the SUN global gathering, review of the SUN CSA strategy, technical review of the pooled fund proposal and monthly update Skype meetings. In addition the EC, particularly Save the Children and Christian Aid, have technical expertise within South Sudan as well as regional and global resources that have supported the development of a vibrant CSA.

The SUN CSA has maintained close liaison with the global CSA SUN Secretariat, with Skype calls held during the formative stage to provide progress updates, share experiences and explore opportunities for capacity-building and funding. Communication with the SUN Network and Regional CSA was also key in building confidence based on experiences shared from other countries in the region.

The inclusion of NGOs such as Nile Hope, United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and the South Sudan Women’s Network for Development within the EC and as members provided diversity and depth to implementation of the SUN CSA strategy, due to their deep understanding of South Sudan. This was also strategic, as a way to build local capacities for civil action and sustainability of SUN interventions, and to align with the ‘grand bargain’ objectives of localising aid.

Members of the SUN CSA were directly involved in developing the three-year strategy, including conducting a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis and using the fish-bone problem analysis tool to identify and prioritise activities, based on collective strength and available opportunities. This exercise resulted in joint ownership and, to some extent, co-funding of agreed activities.

In developing the SUN CSA strategy, flexibility was applied to include a mix of activities that members already had funding for and those that the Alliance believed were essential for jump-starting the strategy. The joint SUN activities, including the presentations made at Cluster meetings, SUN planning meetings and public lectures, were ‘quick wins’ that attracted more members and garnered support for the SUN movement. Utilisation of existing platforms, particularly the various Clusters, was important as Clusters are generally accepted as the coordination mechanism for humanitarian interventions in South Sudan. The Nutrition Cluster was particularly supportive in providing a platform for the sensitisation of CSOs and coordinating registration and other SUN CSA activities.

In forming the CSA, the UN SUN network and the Government were initially supportive through the selection of capable leadership, and later by participating in the development of the strategy and advocacy materials. Under the current partnership cooperation agreement with UNICEF, one activity is being funded on SUN awareness-creation, conducted during World Breastfeeding Week in August 2018. CARE is planning to utilise this funding to create awareness among the private sector.

The timing of the SUN CSA formation, coinciding with the ICWG integration processes, enabled the different Clusters to come together for better integration and deeper impact. This provided an additional platform for members to advocate for a multi-sector approach to address the root causes of malnutrition.

The selection of the SUN leadership by a pre-existing steering committee through a competitive process was a precursor to the successful mobilisation of members. The process gave credibility to the Secretariat, since prospective SUN CSA members believed in the transparency of the selection process. The validation exercise with members that followed was equally critical as it promoted ownership and generated commitment and loyalty; critical to the sustainability of the Alliance. Up to 43 members participated and remained engaged throughout the intense strategy development workshop, while 231 individuals attended the public lecture on integrating nutrition into agriculture value chains. Resolutions from the public lecture included:

1. The need to jointly advocate for funding for nutrition research at Juba University;

2. South Sudan SUN CSA to advocate for incorporation of nutrition education into the curriculum of health courses; and

3. To jointly engage businesses to exercise their social responsibilities by funding nutrition awareness.

Lessons learned

In protracted crises such as in South Sudan, where the nutrition sector still requires external support, it is essential for the Cluster to adopt a needs-based approach to address gaps that may span beyond treatment of acute malnutrition only to multi-sector, nutrition-sensitive interventions. In South Sudan the Nutrition Cluster not only played a central role in mobilising CSOs for SUN, but was at the forefront of defining the minimum package for implementing partners beyond CMAM only. The Cluster was an important player in creating a favourable perception of multi-sector, nutrition-sensitive interventions in an emergency context.

Although the use of consultants to develop strategies is a common tendency, the involvement of members in the problem analysis and prioritisation of interventions provided a learning experience for many members and resulted in more ownership of the document and agreed activities. This was demonstrated through willingness of SUN CSA members to coordinate implementation and even co-fund certain activities through existing budgets, such as the strategy workshop and public lecture. The participation of UNICEF and the Nutrition Cluster, albeit only as observers, added credibility to the process, which was critical in South Sudan, where nutrition activities are largely Cluster-led.

Levels of engagements of member organisations depended heavily on the individuals representing them. For instance, four organisations that were initially very active and supportive eventually became disengaged when their technical staff changed.

Leadership of the SUN CSA was built on mutual respect and the understanding that each member brings unique experience and skillsets to the Alliance. For example, international NGOs such as CARE and CRS have access to information and expertise, including emerging evidence and research in nutrition, while national NGOs such as The Health Support Organization (THESO) are more aware of the South Sudanese context.

Next steps for the CSA

- Support inclusion of advocacy in the Cluster response plan;

- Advocate for financing and development of a South Sudan Nutrition Action plan and M&E plan;

- Scale up implementation of the SUN CSA strategy, including advocacy initiatives, research, awareness creation and capacity-building;

- Strengthen gender mainstreaming in nutrition interventions, including through support to marginalised women and women-led groups in South Sudan;

- Involve the corporate and private sector in implementing, funding and promoting nutrition interventions; for instance, messaging through mobile networks and electronic media; and

- Participate in joint resource-mobilisation initiatives.

Conclusions

The South Sudan experience shows that even in protracted crisis situations it is possible for agencies to make a deliberate shift towards longer-term, preventive programming. Opportunities need to be deliberately created to strengthen the human development nexus. More importantly, this experience shows that it is possible to be far more inclusive by joining efforts and resources. The following are key take-home messages:

- It is possible to scale up nutrition prevention interventions even in emergency settings, provided there is commitment from all stakeholders;

- In emergency settings where the nutrition sector may be weak, the role of the Cluster is critical and may extend beyond current mandates;

- Though often underplayed, involvement of local CSOs – especially women and women-led groups – may result in an exponential increase in ownership.

For more information, please contact Mercy Laker.