Technical brief on the cost of malnutrition

Summary of research1

Location: Global

What we know: Poor nutrition carries a significant economic burden at individual, national and global levels and prevents poverty reduction.

What this article adds: This technical brief presents a new conceptual framework that shows the link between malnutrition and economic costs through four main pathways: mortality, morbidity, impaired physical growth and impaired cognitive function. Through these pathways, malnutrition carries enormous direct and indirect costs to individuals, families and nations – US$3.5 trillion globally. Increased investments in nutrition will bring impressive returns: an extra US$7 billion per year would allow us to meet World Health Assembly (WHA) targets on stunting, anaemia and breastfeeding, saving 3.7 million child lives. Cost-effective interventions should be prioritised to see the greatest gains, including proven nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive actions and more effective nutrition governance. Policy recommendations include calculation of direct and indirect costs of malnutrition at national level, development of standardised metrics to strengthen communication with policy makers, development of a Common Results Framework and generation of rigorous data to assess cost-effective actions and urgently address evidence gaps.

Poor nutrition carries a significant economic burden for individuals and entire economies. It is estimated that undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies and overweight at today’s levels cost the global economy up to US$3.5 trillion (FAO, 2013). This economic burden is a major impediment to government efforts to reduce poverty and to achieve targets such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Choosing the right set of actions to resolve malnutrition requires good evidence of what works in policy terms. Policymakers should make decisions based on the known cost-effectiveness of immediate actions, bearing in mind future accrued costs if appropriate actions are delayed. This technical brief demonstrates that the status quo carries serious economic implications. All policymakers, particularly those in economic planning and finance ministries, must draw on growing evidence of how poor nutrition impacts economic growth. Using a new conceptual framework, this brief illustrates the various pathways by which malnutrition carries fiscal and economic costs. The brief also outlines the impressive returns on investment associated with actions to improve food systems, diets and nutrition worldwide. Investments are needed in country-specific economic analyses of the costs and benefits associated with an accelerated reduction in all forms of malnutrition, and in improvements in the quality and quantity of diets to support this goal.

Poor nutrition carries a significant economic burden for individuals and entire economies. It is estimated that undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies and overweight at today’s levels cost the global economy up to US$3.5 trillion (FAO, 2013). This economic burden is a major impediment to government efforts to reduce poverty and to achieve targets such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Choosing the right set of actions to resolve malnutrition requires good evidence of what works in policy terms. Policymakers should make decisions based on the known cost-effectiveness of immediate actions, bearing in mind future accrued costs if appropriate actions are delayed. This technical brief demonstrates that the status quo carries serious economic implications. All policymakers, particularly those in economic planning and finance ministries, must draw on growing evidence of how poor nutrition impacts economic growth. Using a new conceptual framework, this brief illustrates the various pathways by which malnutrition carries fiscal and economic costs. The brief also outlines the impressive returns on investment associated with actions to improve food systems, diets and nutrition worldwide. Investments are needed in country-specific economic analyses of the costs and benefits associated with an accelerated reduction in all forms of malnutrition, and in improvements in the quality and quantity of diets to support this goal.

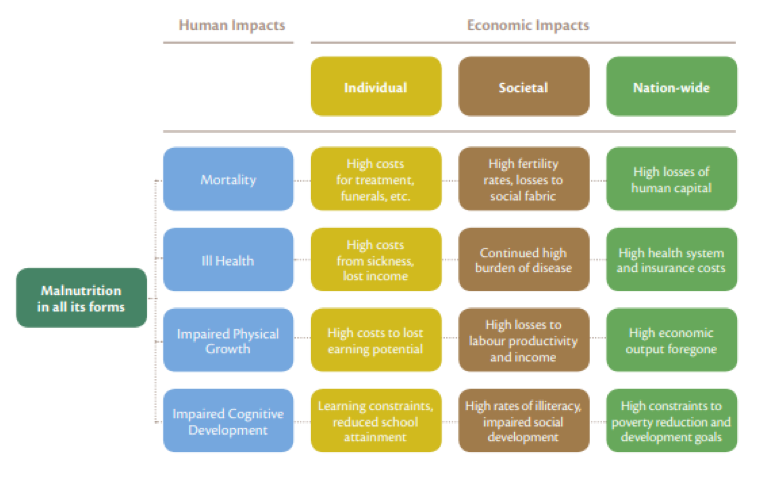

Pathways from malnutrition to economic loss

As well as the direct costs to the global economy of US$3.5 trillion, additional costs of malnutrition are borne by families, in the form of higher medical bills, lost income including due to illness, reduced school performance and later earnings due to cognitive impairment. The various health and other risks associated with various forms of malnutrition vary by gender, age and context. Unfortunately, few data are collected at such disaggregation, making it very difficult to determine the cost and effectiveness of actions for specific groups of individuals. This remains a data gap that should be urgently closed. At the national level, costs include the rising bill associated with disability payments, while losses are squarely tied to lost economic productivity. Within this brief, the authors have grouped these interactions into four pathways (described in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Conceptual framework for understanding the economic impacts of malnutrition in all its forms

Firstly, the authors consider mortality. It is estimated that up to 45% of all preventable child deaths are attributable to undernutrition (Black et al, 2013). Severely undernourished children are up to nine times more likely to die than well-nourished children. Maternal mortality, linked to severe anaemia, and reduced adult life expectancy, linked to obesity and related health complications, are additional manifestations of nutrition-mortality linkages. Preventable mortality represents a loss of human capital that affects families and whole communities.

The second pathway considered is ill health. Treatment costs are borne by families as well as by health and insurance systems. For example, a full course of therapy to save the life of a severely wasted child costs between US$100 and $200 per child. In Ethiopia, the estimated national annual cost of undernutrition (treatment of 3 million underweight children) is US$155 million, 90% of which is covered by families. At the same time, the per capita healthcare costs of treating obesity in the United States alone has been shown to be over 80% higher for severely or morbidly obese adults than for adults with a healthy weight. Focusing specifically on wasting, India’s 45 to 50 million Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) lost to wasting translate to economic losses of more than US$48 billion in lifetime lost productivity (where one DALY is valued at US$1,000).

Thirdly, the authors consider impaired physical growth. Sub-optimal physical growth, often coupled with life-long susceptibility to illnesses, reduces economic productivity through lowered labour productivity or absenteeism from work. The losses to individuals from undernutrition in low-income countries has been estimated as 10% or more of lifetime earnings. The cost to low-income nations of productivity foregone due to undernutrition has been estimated in Uganda as 5% of GDP and in Ethiopia 16.5% GDP. Similarly, in high-income settings like the United States, job absenteeism linked to obesity causes lost output equivalent to $4.3 billion each year, costing employers US$506 annually per obese worker.

The final pathway considered is impaired cognitive development. Poor nutrition from birth, continuing through school and adolescence, impairs cognitive development, delays school-attendance and reduces attainment, resulting in lost employment and socialisation opportunities throughout life. A multi-developing country study that explored the impact of impaired cognitive development on wages suggested that adults who were stunted as children receive almost 20% less in annual income than if they had not been stunted (Shultz, 2002).

The Price of Investing in Good Nutrition – and the Rewards

The World Bank calculated that USD7 billion per year, in addition to existing resource allocations over the next ten years, would allow the world to reach global World Health Assembly (WHA) targets by 2025 for reducing stunting, anaemia in women, and increasing exclusive breastfeeding, while also better managing the impacts of wasting. Estimates indicate that this would result in 3.7 million child lives saved, more than 65 million fewer children being stunted, and 265 million fewer women suffering from anaemia compared to 2015 (Shekar, 2015). The recent ‘Cost of Hunger’ analysis for 12 countries in Africa found that a halving of the prevalence rates of child stunting by 2025 would lead to savings of US$3 million per year for Swaziland, to US$133 million for Egypt and as high as US$376 million in Ethiopia (FAO, 2014).

A recent study found that a 10% rise in GDP per person predicts an 11% decrease in extreme poverty (individuals living on US$1.25 per day), but less than a 6% reduction in child stunting. For policymakers to achieve the goal of ending all forms of malnutrition will therefore require actions that go beyond macroeconomic growth and promoting sufficient household incomes that meet the basic needs, including access to health services, clean water, enhanced hygiene as well as women’s empowerment. Investments in nutrition-sensitive social protection programmes also have the potential to improve nutrition and contain costs by strengthening household resilience.

Spending must be prioritised on cost-effective interventions to reduce undernutrition needed at scale, including universal salt iodisation, micronutrient supplementation (vitamin A, iron, folic acid and calcium), food fortification, promotion of exclusive breastfeeding and use of high-quality complementary foods, balanced energy protein supplementation of undernourished individuals and the treatment of severe and moderate wasting. The return on these investments would reduce wasting by 60% and stunting by 20%, resulting in returns to investment of the order of 18-to-1 on average across high-burden countries.

These activities must be complemented by action in other policy domains, including investments in agriculture, marketing and trade of food to limit post-harvest food losses, engaging with the private sector to produce nutrient-rich, health food products and social protection and income-support for nutritionally vulnerable groups.

More effective governance for nutrition is also needed, such as establishing and supporting institutional and individual capacities and resources needed to promote good policies and ensure effective implementation of good programmes. A study by the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement showed that the average annual cost associated with individualised plans for nutrition-specific interventions is estimated to be US$200 million and for nutrition-sensitive actions US$1496 million. Investments in nutrition governance mechanisms, typically involving information management and coordination, advocacy and communications and systems capacity-building, come to US$114 million (SUN, 2014).

Recommendations to policymakers

Based on these findings, the Global Panel recommends that:

1. Governments should calculate the direct and indirect cost of malnutrition in all its forms for their own country.

2. Standardised metrics must be developed to support more effective communication of findings to policymakers.

3. Viable options for policy and programme interventions across the food system must be identified and costed.

4. Establish a national Common Results Framework to shape the monitoring and reporting on progress.

5. Generate rigorous data to support ongoing assessment of cost-effective actions across the food system and food environment.

6. Urgently address knowledge gaps and data deficiencies on the costs and benefits of national investments in infrastructure enhancement; processing and food transformation; wholesale and retail incentives for delivery of affordable and desirable nutritious and healthy foods; and drivers of dietary choices and policy options for supporting better informed choice.

Endnote

1Global Panel. 2016. The cost of malnutrition. Why policy action is urgent. London, UK: Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition.

References

Black R et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low income and middle-income countries. The Lancet 2013. 382(9890): 427-451.

FAO 2013. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. State of Food and Agriculture 2013: Food systems for better nutrition. 2013 Rome, Italy.

FAO 2014. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Understanding the true cost of malnutrition. 2014. [cited 27th April 2016]. Available at www.fao.org/zhc/detailevents/en/c/238389/

Schultz T. Wage gains associated with height as a form of health human capital. American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 2002. 92, 349-353.

Shekar M et al. Investing In Nutrition: The Foundation For Development and Investment Framework To Reach The Global Nutrition Targets. 2015. Washington, USA.

SUN 2014. Scaling Up Nutrition. Planning and costing for the acceleration of actions for nutrition: experiences of countries in the Movement for Scaling up Nutrition. 2014. New York, USA.