Training Care Groups on sexual and gender-based violence in rural Niger

By Bruce W Larkin and Julie Tanaka

Bruce W Larkin is a doctoral candidate (MD) at the Medical School for International Health at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel. He formerly worked as the Health & Nutrition Programme Manager for Samaritan’s Purse Niger office. Bruce has public health experience in Bangladesh, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon and Niger.

Julie Tanaka is the Senior International Nutrition Advisor for Samaritan’s Purse. She helps field offices around the world with programme design, proposal review, implementation, nutrition surveys, trainings, monitoring and evaluation, and emergency relief.

The authors would like to thank Samaritan’s Purse for funding the project and would like to acknowledge Emma Smith Cain and Saley Inoussa for their help in the development of this study and the Samaritan’s Purse Niger team for their assistance in the implementation of this project.

Location: Niger

What we know: Nutrition insecurity is exacerbated by major gender inequalities. Intimate partner violence (IPV) can negatively affect the nutrition status of women and their children.

What this article adds: Major gender inequalities exist in Niger; physical violence against women is ubiquitous. Training on sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) was integrated into a pre-existing care group programme in rural Niger providing cascading training on infant and young child feeding and maternal and child health to 5,000 women and men. SGBV training was provided over two months to uneducated health promoters, who in turn trained men and women in care groups, who each then trained 10-12 neighbours of the same gender. A survey examined SGBV attitudes and knowledge of 1,374 participants at different levels. Overall, the percentage of correct attitude responses increased from 43.0% to 71.9%, with a similar improvement among women and men. There were improvements in attitudes towards physical violence, forced sexual intercourse and roles of wives in financial decision-making, indicating potential to transmit SGBV messaging through this model. Misinterpretation of two knowledge areas indicates need for closer attention and follow-up of more nuanced/complex topics. Overall, pilot results demonstrate that SGBV messaging can be successfully integrated into Care Group (CG) interventions.

Background

Niger is reportedly one of the most difficult places in the world for women to live. Major gender inequalities persist and women and girls are frequent victims of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). The Nigerien government reports that physical violence against women is ubiquitous in Nigerien society (MPFPE, 2008) and that 70% of women believe that men may justifiably beat their wives (INS, 2007). Malnutrition is also a persistent and widespread problem in Niger, which has a global acute malnutrition (GAM) rate of 10.3% (classified as ‘serious’) and stunting prevalence of 42.5% among children under the age of five (U5) (PDES, 2016). Research shows that nutrition insecurity can be exacerbated by gender inequalities, as women and girls frequently lack equal access to nutritious foods (younger children and females are typically fed last and least during mealtimes), clean water and healthcare (IASC, 2015). There is also evidence of associations between intimate partner violence (IPV) and low-birth weight (LBW) (Mezzavilla and Hasselmann, 2016), anaemia and low body mass index (BMI) for female victims (Ackerson and Subramanian, 2008) and stunting among children in affected families (Rico et al, 2011). Disagreement on how food-resources should be allocated may also result in IPV (IACS, 2015).

The lack of gender equality is particularly troubling in rural areas, such as the Banibangou Commune along the Mali border. This under-resourced area is vulnerable to attacks by bandits and Islamic extremists associated with Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. According to focus group discussions conducted by Samaritan’s Purse, speaking out on SGBV within the community is taboo. Local authorities have been known to prohibit victims from voicing their complaints to the police and victims reportedly avoid seeking help from the local health centres out of fear that patient confidentiality will not be respected. This region also suffers from chronic drought and food insecurity. A February 2017 survey of 11 villages in Banibangou Commune revealed a 26.5% (95% CI = 20.5%-32.6%) GAM prevalence among children aged 6-23 months, a 17.4 % (95% CI = 12.23%-22.66%) SAM prevalence, and only 7.96% (95% CI = 4.22%-11.70%) of children consuming a minimum acceptable diet, as defined by WHO (SPN, 2017).

Samaritan’s Purse implemented and had oversight of a community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) programme between 2006 and 2016 in Banibangou Commune, funded by WFP. In 2016, CMAM support was phased out, since WFP ceased funding non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to oversee CMAM programming due to budgetary constraints; responsibility was handed over to the Ministry of Health (MoH) and the Bridging Gaps in Community Health (BGCH) project was launched (funded by Samaritan’s Purse) to better address the community’s maternal and child health (MCH) needs and prevent malnutrition. The BGCH project has used Care Groups (CGs) to regularly train over 5,000 adults in infant and young child feeding (IYCF), MCH practices and birth spacing. Samaritan’s Purse also engaged local imams to discuss the compatibility of birth spacing, SGBV and the Koran (Box 1). As a result of the training, many villagers reported feeling empowered by their imams to obtain contraceptives.

Given the tremendous gender needs in Niger, Samaritan’s Purse sought to pilot a project in all the ongoing Care Groups to test whether trained illiterate adults could successfully transmit key SGBV messages using the Care Group methodology. The pilot lasted for two months, with six hour-long trainings, and included adapted lessons from Phase 1 of Sasa! Faith training manual (Michau and Siebert, 2016).

Methodology

The CG methodology involves bi-weekly gathering of community volunteers of reproductive age (referred to as “Leader Mothers” (LMs) and “Leader Fathers” (LFs)) into CGs. Through these CGs, trainings are provided by Health Promoters, who are community volunteers recommended by community leaders, literate, trained by the MoH on MCH and IYCF principles, and given a small stipend and means of transportation from Samaritan’s Purse. The Health Promoters equip LMs and LFs to relay MCH and IYCF messages to 10-12 of their neighbours of the same gender through Neighbourhood Groups (NGs). This cascading training methodology has been demonstrated to increase coverage of key child survival indicators (George et al, 2015). Men and women from the same households were enrolled in separate CGs to ensure that husbands allow their wives to apply the lessons learned. Through this method Samaritan’s Purse provided SGBV training over two months from September to November 2017 to all Health Promoters in the existing programme, who went on to train 302 LMs (who themselves went on to train 3,113 neighborhood women) and 217 LFs (who trained 2,391 neighborhood men).

The SGBV training comprised two modules used to train CG members and was heavily adapted from Phase 1 of Sasa! Faith. Samaritan’s Purse developed laminated images to accompany the lessons. Each module was taught over three one-hour sessions. Key messages from the modules included:

- Types of social power and power dynamics

- An explanation of ‘equality’, defined as all individuals having the same rights, opportunities and life chances, regardless of gender or age

- The types of violence commonly enacted against women

- The need for victims of sexual violence to be referred to a health centre within 72 hours of any incident

- The different ways in which violence impacts groups of people within society.

Six female CGs and five male CGs were randomly selected to participate in SGBV knowledge and attitude surveys to evaluate the pilot project. Each of the LMs and LFs included in these groups also then carried out the survey with members of their NGs. In addition, one set of ten LMs, ten neighbourhood women (NW), ten LMs and ten neighbourhood men (NM) were separately included in focus group discussions (FGDs).

Results

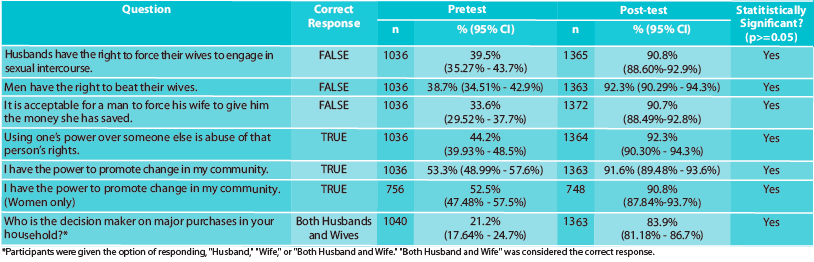

A total of 1,374 participants (757 female and 617 male, of whom 69 were LMs, 688 NW, 57 LFs and 560 NM) were surveyed on the same questions pertaining to SGBV before and after the two-month pilot (Tables 1 and 2).

Overall, the percentage of correct responses increased from 43.0% (95% CI=41.6-44.5%) to 71.9% (95% CI=70.8-73.1%) between the pretest and post-test, indicating that illiterate adults could successfully learn and teach SGBV topics. The overall rate of improvement in attitudes between pre- and post-tests was similar between LMs/LFs and NM/NW (40.0% to 74.4% and 43% to 71.7% respectively) and between women and men (42.9% to 71.8% and 43.3% to 72.1% respectively). Of note, the percentage of beneficiaries reporting that men have the right to beat their wives decreased from 61.3% to 7.7% (Table 1). The percentage reporting that husbands have the right to force their wives to engage in sexual intercourse similarly decreased from 60.5% to 9.2%.

The training appeared to influence how beneficiaries understood the roles of wives in financial decisions. When asked who makes financial decisions on major purchases, the percentage of respondents who said “both the husband and the wife” (compared to “just the husband” or “just the wife”) increased from 21.2% to 83.9%. The percentage of respondents believing that men may force their wives to give them the money she has saved decreased from 66.4% to 9.3%. This is significant, given that men are the main financial decision-makers in Nigerien society (Save the Children, 2018).

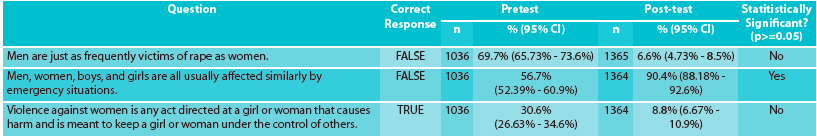

Table 2: Distribution of correct responses to SGBV knowledge questions in pilot pre-test (September 2017) and post-test (November 2017) among BGCH II CG beneficiaries

The percentage of participants providing correct responses decreased for two of the three more complex knowledge questions asked regarding whether men are victims of rape as frequently as women and how violence against women is defined (Table 2). It is plausible that the trainees would have mastered these concepts if the training was prolonged.

Discussion

Pilot results demonstrate that SGBV messaging can be successfully integrated into CG interventions. Although most of the participating LMs and LFs were illiterate adults with no preconception of gender rights, attitudes on several taboo topics changed over a two-month period.

As many nutrition programmes focus on the most vulnerable groups within society (pregnant and lactating women and children U5), nutrition interventions provide a unique platform for protection programming. SGBV is not currently explored in the standard CMAM case management undertaken by the MoH. CGs, in particular, provide an inexpensive method of efficiently disseminating SGBV messages to men and women, as well as empowering women by allowing them to take an active role in teaching their neighbours. Future studies should further measure the effects of promoting SGBV on IYCF and nutritional status indicators over an extended period of time.

There are limitations to using CGs to transmit SGBV messaging. Some concepts, such as the definition of violence towards women (Table 2), may have been too complex for the participants to comprehend. It appears that many beneficiaries misapplied gender equity to mean that both men and women are victims of rape equally (Table 2). Future use of CGs in SGBV programming will need to place additional emphasis on the nuances of gender equity. It is possible that these unexpected results could also be attributed to the short duration of the pilot. Over an extended project life-cycle concepts would be repeated and project staff would be able to identify and address gaps in beneficiary comprehension of subject material.

The use of a modified version of Sasa! Faith proved to be an effective curriculum for the rural Muslim audience. The curriculum aims to promote gender equality by encouraging participants to reflect on how power dynamics affect interpersonal relationships. Subsequent lessons guide participants to apply the concept of power to gender equity and violence against women. This varies drastically from programmes that rely on dogmatic instructional messaging against SGBV (Michau et al, 2015). This subtle approach was apt for the audience, who may have been resistant to a more overt form of messaging.

Samaritan’s Purse took several precautions before exposing community members to the sensitive topic of SGBV; issues of sexual violence are extremely taboo in this context. Community leaders and village chiefs were informed of these trainings before they took place. Prior to the pilot, local imams were trained on the importance of birth spacing and SGBV. Male CG participants tended to be receptive to SGBV lessons once they were informed that their imams approved the trainings. Focus group discussions illuminated the fact that the community lacks protection services.

Conclusions

Even with uneducated instructors, certain SGBV messages can be effectively transmitted using the CG model. As SGBV is a pertinent issue, it is suggested that nutrition actors incorporate SGBV messaging in their behaviour-change programming. Nutrition insecurity is linked to gender inequality and improved women’s empowerment, and gender equity can affect intra-household food distribution; women’s decision-making power over income, time and childcare practices; and household division of labour. All these things can affect a woman’s ability to practice the kinds of IYCF behaviours that lead to improved nutritional status for children during their most vulnerable years. These educational sessions, however, should be closely monitored to ensure that nuanced topics are clearly understood.

Due to security concerns, Samaritan’s Purse withdrew from the Banibangou Commune in December 2017. Samaritan’s Purse continues health and nutrition programming in other areas in Niger.

Testimonials (collected from women only):

After the very first SGBV pilot training with Leader Mothers, one of the women exclaimed, “I never realised that it wasn’t okay for men to beat their wives!”

During the time of the pilot, the daughter of Sarratou*, a project beneficiary, was being forced into marrying her relative. Her daughter complained to the local police, who told the family that the girl had the right to refuse the marriage. Sarratou’s family was furious and wanted to disown the girl. The SGBV training that Sarratou received, however, helped her understand that her daughter should not be married against her will. Fortunately, Sarratou was able to convince her family that they should allow her daughter to remain unmarried and peacefully stay in their home. Sarratou now tells her female neighbors to avoid being given in a forced marriage.

Mariama* participated as a BGCH Leader Mother and was encouraged by the SGBV lessons. “With the pilot [lessons on violence against women], I have understood that wives must also be involved in the family’s financial decisions.”

Mariama is now taking the initiative to become more financially independent in order to better take care of and protect herself and her children. She is also advising her neighbors to do the same: “I urge the other mothers to send their daughters to school in order to prevent the girls from falling into the same mistakes as their mothers.”

* Names have been changed for reasons of confidentiality.

Box 1: Description of programme to train imams in birth spacing and SGBV

In June 2017 Samaritan’s Purse held a training with 14 imams on the importance of birth spacing and addressing gender-based violence. Both issues are relevant in Niger, which has the world’s highest fertility rate at 7.6 live births per woman (World Bank, 2015). Negligence of family planning contributes to the high malnutrition rate in Niger. Religious leaders were targeted for the training in part to address the commonly held belief that family planning is a western ploy to curb Islamic population growth. The training emphasised that the purpose of birth spacing is to protect the health of the mother and child. Pre-test and post-test results demonstrated that the percentage of participants believing that birth spacing involves the permanent cessation of pregnancies decreased from 67% to 0%. The percentage of imams believing that religious and community leaders have the responsibility to advocate for girls who are victims of sexual violence increased from 92% to 100%. At the end of the training, each imam proposed ways that they would personally address birth spacing and SGBV in their communities.

For more information, please contact Julie Tanaka.

References

Ackerson LK & Subramanian 2008. Domestic violence and chronic malnutrition among women and children in India. Am J Epidemiol. 167(10):1188-96.

George et al 2015. Evaluation of the effectiveness of care groups in expanding population coverage of Key child survival interventions and reducing under-5 mortality: a comparative analysis using the lives saved tool (LiST). BMC Public Health, 15:835.

IASC 2015. Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) 2015. Guidelines for Integrating Gender-Based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Action: Reducing risk, promoting resilience and aiding recovery.

INS 2007. Institut National de la Statistique 2007, Enquête de base dans 11 communes du programme Niger Unicef.

Mezzavilla RS & Hasselmann MH 2016. Physical intimate partner violence and low birth weight in newborns from primary health care units of the city of Rio de Janeiro. Rev. Nutr. vol.29 no.3.

Michau L & Siebert S 2016. SASA! Faith: A Training Manual to prepare everyone involved in SASA! Faith, Raising Voices.

Michau L, Horn J, Bank A, Dutt M, Zimmerman C 2015. Prevention of violence against women and girls: lessons from practice. Lancet, 385(9978):1672-84

MPFPE 2008. République du Niger, Ministère de la Promotion de la Femme et de la Protection de l’Enfant (MPFPE) 2008. Analyse de la situation de la situation de l’Enfant et de la Femme au Niger – 2008.

PDES 2016. Ministère du Plan 2016, Plan de Développement Economique et Social (PDES) 2017-2021 : La Nutrition, Une Priorité. Papier De Positionnement. Gouvernement De La République Du Niger.

Rico E et al 2011. Associations between maternal experiences of intimate partner violence and child nutrition and mortality: findings from Demographic and Health Surveys in Egypt, Honduras, Kenya, Malawi and Rwanda. J Epidemiol Community Health. 65(4):360-7.

Samaritan’s Purse Niger 2017. Diffa Gender Analysis.

Save the Children 2018. Mainstreaming Gender-Based Violence Considerations in Cash-Based Interventions: A Case Study from Zinder, Niger.

World Bank 2015. Fertility Rate, Total (births per Woman). The World Bank Group. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN