Barrier analysis of infant and young child feeding and maternal nutrition behaviours among IDPs in northern and southern Syria

By Shiromi Michelle Perera

Shiromi Michelle Perera is a Technical Officer with the Technical Unit at International Medical Corps (IMC), Washington DC. Shiromi has coordinated and conducted barrier analysis assessments in Sierra Leone, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Ethiopia and Sudan.

The author would like to acknowledge the support provided by Majd Alabd (Consultant), Bonnie Kittle (Consultant), Suzanne Brinkmann (International Medical Corps), Andi Kendle (International Medical Corps) and Adelaide Challier (Save the Children). The author also acknowledges the Turkey Nutrition Cluster and its partners, including Wigdan Madani (UNICEF), Mona Maman (Physicians Across Continents) and Dr Saja Abdullah (Whole of Syria Cluster Coordinator), as well as the assessment trainers, supervisors and data collectors. Special thanks to the following trainers: Kotham Saaty (Physicians Across Continents), Anas Barbour (Human Appeal) and Feras Ahmed (USSOM), Amer Basmaci (Consultant) and Marwa AlSubaih (Syria Relief and Development). The author is also thankful to the communities and especially the Syrian mothers who gave their time to be part of this assessment. Special thanks go to UNICEF for financial support to conduct this barrier analysis assessment.

This barrier analysis report was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in the technical support for this assessment and UNICEF for its implementation. The contents are the responsibility of the Technical Rapid Response Team (Tech RRT) and the Nutrition Cluster and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNICEF, USAID or the US Government.

Location: Syria

What we know: Promoting and supporting optimal infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices and maternal nutrition are essential interventions in crisis-affected populations.

What this article adds: A barrier analysis regarding several key infant feeding and maternal nutrition practices was commissioned by UNICEF in Syria in 2017. It was born of little success in existing interventions to change prevalent practices. Significant barriers and enabling factors to change were determined among ‘doers’ and ‘non-doers’ with regard to exclusive breastfeeding, minimum dietary diversity and an additional meal per day in pregnancy. These included lack of correct knowledge and misconceptions; lack of access to markets and availability of diverse foods; inability to afford food; stress; lack of support from critical family members; and lack of time to prepare meals. Improved access to IYCF and maternal nutrition services are needed, with support for mothers and pregnant women more effectively integrated into other sectors, particularly food security, agriculture, livelihoods and reproductive health. Detailed recommendations are informing current and future programming by Nutrition Cluster partners in specific districts and have wider relevance in Syria. This experience reflects that barrier analysis is possible in an insecure/emergency contexts.

Background

The Syrian crisis continues to be one of the worst humanitarian and protection crises of our time, taking a significant toll on the lives of the Syrian people and impacting all basic needs. Over half of the population has been internally displaced, resulting in many families living in camps, informal settlements and collective centres throughout the country. In 2016 the Whole of Syria (WoS) Nutrition Sector response reached 3.4 million children and pregnant and lactating women (PLW) affected by the crisis with a range of preventative and therapeutic nutrition interventions (WoS, 2016). Included in this were efforts by the Nutrition Cluster and its partners to promote and support optimal infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices, as well as maternal nutrition, as priority life-saving interventions. Nevertheless, a knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) survey, conducted in February 2017, indicated that the prevalence of certain IYCF behaviours was either low or largely unchanged compared to the results of nutrition surveys carried out before the response. Three IYCF behaviors in need of further investigation were: exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) (30.9%); complementary feeding for minimum dietary diversity (CF-MDD) (57.3%); and eating an extra meal during pregnancy (40.3%). As co-lead of the Nutrition Cluster, UNICEF commissioned a barrier analysis (BA) to determine the reasons behind prevalent IYCF and maternal nutrition practices among internally displaced people (IDP) in camp and urban settings in the Aleppo, Idlib and Dar’a Governorates in order to better tailor partner programme activities. This article summarises findings and recommendations from this first-ever BA on feeding practices in Syria, conducted in August 2017 in northern and southern Syria.

Methodology

An initial two-day training of trainers (TOT) was conducted in Gaziantep, Turkey, among Nutrition Cluster partner organisations from north and south Syria. The training included content on internationally recognised BA guidelines (Kittle, 2013), questionnaire development and interviewing skills and the use of KoBo, a free, open-source tool for mobile data collection. Training was cascaded to 15 data collectors and two supervisors in the north (Physicians Across Continents and Human Appeal) and 10 data collectors and two supervisors in the south (Syria Relief and Development).

Following this, three cross-sectional surveys were carried out in camp IDP and urban IDP locations in north and south Syria, chosen according to the presence of operational nutrition programmes and security/accessibility. Purposive samples of 90 Syrian mothers (45 ‘doers’ (those who practice the behaviour) and 45 ‘non-doers’ (those who do not)) were selected for each behavior. Groups included mothers of infants aged 0-<6 months exclusively breastfeeding (or breastfeeding but not exclusively); mothers of children age 6-23 months feeding children meals containing foods from at least four of seven specified food groups per day (or not); and pregnant mothers who consume an extra meal per day during pregnancy (or not).

Mothers were first screened and classified as ‘doers’ or ‘non-doers’, after which they were asked questions according to their classification to identify which of the 12 specified determinants of behaviour change acted as barriers to the particular behavior among ‘non-doers’ and which facilitated its adoption among ‘doers’. Data from closed-ended questions were collected with KoBo using mobile devices, which is an uncommon adaptation to the BA approach but worked well in this emergency context. Coding of qualitative responses was achieved through an iterative group process with each team, using various online applications, depending on connectivity. Codes were then tabulated and recorded for analysis in a BA tabulation Excel spreadsheet. Findings were interpreted by the BA team and presented at a results workshop of participating partners, and later with Nutrition Cluster partners to help inform interpretation of results and recommendations.

Results

In total, 551 mothers were interviewed in north (n=271) and south Syria (n=280). The north was stratified into camp IDP and urban IDP locations; specifically, Atmeh Camp in Idlib Governorate, Al’Mara District in Idlib Governorate and Jebel Saman District in Aleppo Governorate. The south was stratified into urban IDP locations in Dar’a Governorate; specifically, Tafas and Hrak Districts. In total, 11 determinants in the north and 5 determinants in the south were found to be significant for EBF; 11 determinants in the north and 8 determinants in the south for CF-MD, and 11 determinants in the north and 9 determinants in the south for an extra meal during pregnancy.

Exclusive breastfeeding

Common barriers experienced by ‘non-doers’ included maternal stress, perception that the baby is unsatisfied, maternal anemia, physical issues with breastfeeding for the mother (breast problems) and baby (stomach problems, colic, teething) and lack of support from the husband. Mothers and mothers-in-law were described by ‘non-doers’ as people who disapprove of EBF. Factors that facilitated EBF indicated by ‘doers’ were knowledge of IYCF, family support, private spaces to breastfeed, access to and consumption of diverse foods by the mother in order to produce milk, and having enough and continuous milk. Barriers identified by ‘doers’ of particular relevance were market-access issues and concerns related to breast problems (pain in breasts or inflammation in nipples).

While both ‘doer’ and ’non-doer’ mothers demonstrated adequate knowledge about the positive and negative consequences of EBF, they had several misconceptions, such as thinking that breastfeeding is a “waste of time”, the baby is left unsatisfied, breastfeeding changes breast shape and leads to maternal health problems (loss of weight, illness, loss of calcium, loss of immunity) and problems in the family. Additional significant determinants were perceived access (‘doers’ and ’non-doers’ stated it was “somewhat difficult” to get the support needed to EBF); perceived cues for action/reminders (‘non-doers’ were more likely to say it was “somewhat difficult” to remember to give only breastmilk for the first six months); perceived risk of malnutrition and diarrhoea; perceived severity of malnutrition and diarrhoea; perceived efficacy of EBF (‘doer’ and ‘non-doers’ do not fully understand the relationship between EBF and malnutrition/ diarrhoea); divine will (‘doers’ were more likely to say that Allah may cause malnutrition or diarrhea); and culture (‘doers’ were more likely to say that there are cultural rules/taboos against EBF).

Minimum dietary diversity (MDD) in complementary feeding

Some of the barriers for ‘non-doers’ included not enough food preparation time for mothers due to work outside the home, the child not accepting prepared food, the child being sick or having thyroid problems, lack of food diversity in markets and being unable to afford diverse foods. ‘Non-doers’ indicated that sisters and aunts disapprove of feeding a diverse diet to children. ‘Doers’ indicated several facilitating factors, such as support from husband and family members, access to markets, availability of foods in the house, enough time to feed their child, the child loving/wanting food, having electricity to cook food, and receiving advice about complementary feeding. Stated barriers for ‘doers’ of particular relevance were interference by family members, distance to markets and lack of time due to the mother working outside of the house.

Some lack of knowledge and misconceptions were found, such as mothers perceiving that a diverse diet does not provide immunity and leads to children getting sick from food poisoning or intestinal complications. Additional significant determinants were perceived access (‘non-doers’ indicated that it was “very difficult” to get food from at least four of the seven food groups), perceived cues for action/reminders (‘non-doers’ were more likely to say it was “somewhat difficult” to remember to include foods from at least four of the seven food groups during meal preparation), perceived risk of malnutrition, perceived severity (‘doers’ considered becoming malnourished as only “somewhat serious”), perceived action efficacy (‘non-doers’ did not fully understand the relationship between a diverse diet and malnutrition), divine will (‘non-doers’ were more likely to say Allah causes malnutrition) and culture (‘doers’ were more likely to say there are cultural rules/taboos against feeding their child a diverse diet).

Extra meal during pregnancy

Some of the barriers for ‘non-doers’ included pregnancy-related sickness (vomiting, pressure, stomach pain), markets being far away, lack of money to buy foods, lack of privacy, lack of time to cook food, not receiving food baskets from non-governmental organisations and regular displacement. ‘Non-doers’ indicated that no one would disapprove of eating an extra meal during pregnancy. Facilitators for ‘doers’ included having a supportive husband, availability of food in the house and accessible markets, kitchen appliances to store and cook food, advice from nutrition workers, provision of an NGO food basket, and the mother having an appetite and not being stressed or sick. Barriers for ‘doers’ of particular relevance included lack of availability of food in the house and the mother being too tired or lacking an appetite to eat an extra meal.

Some lack of knowledge and misconceptions were revealed, with mothers perceiving that an extra meal leads to weight gain, sickness, feeling lazy and increased blood pressure when eating certain foods. Additional significant determinants were perceived access (‘non-doers’ were more likely to indicate that it was “very difficult” to access what they need to eat an extra meal), perceived cues for action/reminders (‘non-doers’ were more likely to say it was “very difficult” to remember to eat an extra meal), perceived risk the baby will be born too weak and small, perceived severity (‘doers’ and ‘non-doers’ perceived the baby being born too weak and small as “very serious”), perceived action efficacy (‘non-doers’ did not fully understand the relationship between eating an extra meal and giving birth to a healthy baby), divine will (‘non-doers’ were more likely to say that Allah wants them to eat an extra meal) and culture (‘non-doers’ were more likely to say there are cultural rules/taboos against eating an extra meal).

Discussion and recommendations

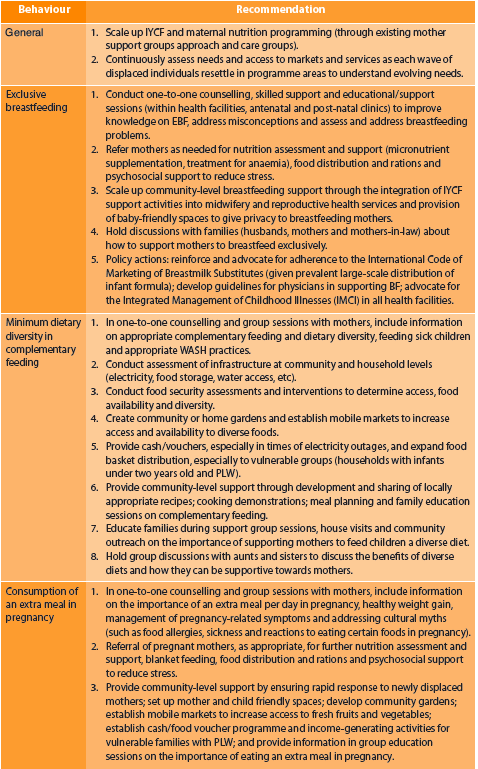

This article reflects that barrier analysis is possible in an insecure/emergency context. It applied KoBo, which is not commonly used with BA, and adapted training and coding methods for remote application. Results show various determinants that create barriers to mothers properly practicing the three assessed behaviours, including lack of correct knowledge and misconceptions; lack of access to markets and availability of diverse foods; inability to afford food; stress; lack of support from critical family members; and lack of time to prepare meals. Results suggest that improved access to IYCF and maternal nutrition services are needed and that support for mothers of infants and young children and PLW must be more effectively integrated into other sectors, particularly food security, agriculture, livelihoods and reproductive health to ensure that the multiple needs of this group are addressed. Recommendations, summarised in Table 1, build on existing programme activities and plans. Although recommendations were tailored to specific districts, they will also likely benefit similar programming locations in northern and southern regions. Following this assessment, the Nutrition Cluster partners held a workshop to begin planning how to move forward with these recommendations. The author developed a social behavior change strategy to aid the Cluster in the design, implementation and monitoring and evaluation of the recommended activities.

Table 1: Summary of recommendations

The full report can be accessed here.

For more information, please email Shiromi Perera.

References

Nutrition Cluster IYCF-E Operational Strategy 2017- 2020.

Whole of Syria (WoS) Nutrition Sector Bulletin, Issue 2 July-December 2016.

Kittle, Bonnie. 2013. A Practical Guide to Conducting a Barrier Analysis. New York, NY: Helen Keller International.