UNHCR experiences of enabling continuity of acute malnutrition care in the East, Horn of Africa and Great Lakes region

By Naser Mohmand

Naser Mohmand is currently working with UNHCR as Senior Regional Nutrition and Food Security Officer in the East, Horn of Africa and Great Lakes region (EHAGL). Naser is a nutrition specialist with a master’s degree in public health nutrition (MPH) and 23 years of experience in different technical and managerial positions in emergency and post-emergency contexts with various international humanitarian organisations across Asia and Africa, as well as in UNHCR headquarters in Geneva.

The UNHCR Regional Service Centre would like to acknowledge its partnership and collaboration with other United Nations Agencies and international and national non-governmental organisations, as well as the governments and communities in the region that generously host refugees.

Location: East, Horn of Africa and Great Lakes (EHAGL) region

What we know: Acute malnutrition treatment is a key component of UNHCR’s global public health strategy and an essential part of its wider protection mandate.

What this article adds: There are an estimated 5.21 million refugees and asylum seekers in the EHAGL region. Global acute malnutrition (GAM) prevalence remains high; 20% of refugee sites exceed the >15% emergency threshold. UNHCR-led acute malnutrition management involves community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM), the protection, promotion and support of infant and young child feeding, and multi-sector activities. This involves close collaboration with existing national health and nutrition programmes in refugee-hosting communities and United Nations (UN) agencies and implementing partners. Through global and country-level agreements, UNICEF provides supplies for severe acute malnutrition (SAM) treatment programmes and World Food Programme supports and provides supplies for targeted and blanket supplementary feeding programmes. In refugee sites, most SAM and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) treatment services are co-located with one implementing partner. Challenges to achieving continuum of treatment include shortfalls in nutrition product supplies (compensated by UNHCR contingencies), low capacity of host heath systems, lack of national programmes for MAM, and shortfalls in food and non-food assistance. Adequate funding, sustained product supplies and continued technical support through a collaborative, interagency approach are critical to addressing ongoing complex needs in the region.

Context

Displacement is a major shock that often leads to a loss of livelihoods, entitlements, food insecurity, sub-optimal infant and young child feeding (IYCF) and morbidity linked to environmental, hygiene and shelter concerns. As a result, undernutrition in its multiple forms, including wasting, stunting and micronutrient deficiencies, is highly prevalent in refugee populations. Maintaining adequate nutrition and preventing malnutrition is an essential part of UNHCR’s wider protection mandate, especially with regard to refugee women and children, who are the majority (81%) of refugee populations. With regard to nutrition and food security, in accordance with UNHCR’s global public health strategy, UNHCR strives to prevent undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies, treat malnutrition, and provide up-to-date food security and nutrition information to inform effective programming.

The New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants was adopted in 2016, reaffirming the importance of the international refugee regime. It contains a wide range of commitments by member states to strengthen and enhance mechanisms to protect people on the move. Based on this, the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework (CRRF)1 has been launched to forge a stronger, fairer response to large refugee movements and situations of prolonged displacement. Fundamental to both the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR) and CRRF is recognition of the importance of supporting communities that host large numbers of refugees and to promoting inclusion and integration of refugees in national systems. This requires the engagement of development actors from an early stage of response, bringing national and local authorities together with international, private and civil society actors to generate a ‘whole-of-society’, integrated approach to refugee response. To date, six countries in the region (Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Uganda and Rwanda) have applied the CRRF.

UNHCR coordinates with relevant government ministries (such as refugee affairs authorities, ministries of health and ministries of education), other United Nations (UN) agencies (such as World Food Programme (WFP), the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF, Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)); and international and national non-governmental organisations (NGOs). UNHCR also partners with many other agencies to ensure availability, access, integration and sustainability of quality public health nutrition services for refugees and other persons of concern. Memoranda/letters of understanding (MOU/LOU) govern and inform arrangements with other UN agencies, cooperating partners and governments, as relevant, to deliver services to those under UNHCR’s protection.

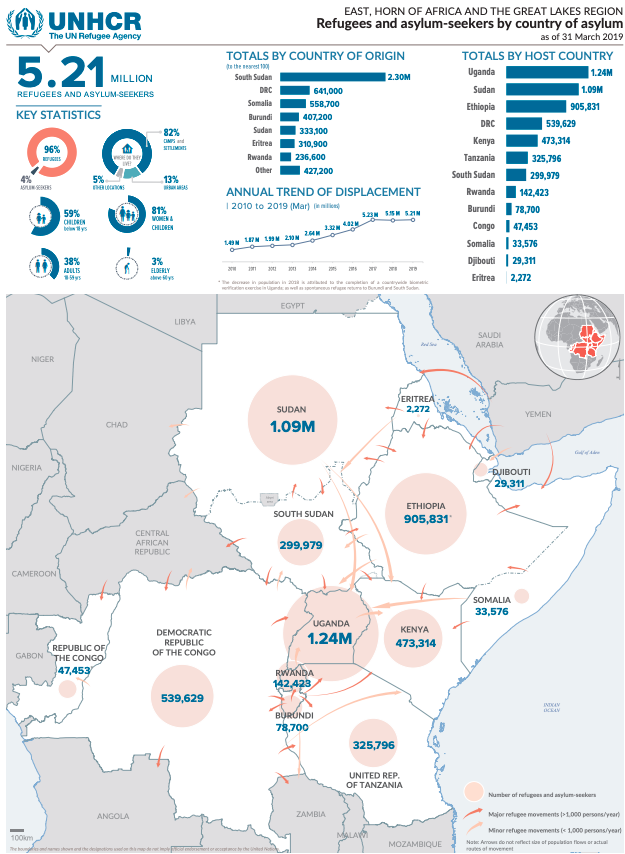

Refugee operations in the East, Horn of Africa and Great Lakes (EHAGL) region

Ongoing conflict compounded by food insecurity has resulted in major displacement in the EHAGL, with 5.21 million refugees and asylum seekers in the region, around 81% of whom are women and children. The highest number of refugees in the region originate from South Sudan, from where around 2.3 million people have fled, with continued new influxes into neighbouring countries. There are also large influxes of refugees from Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Somalia, Burundi, Central Africa Republic, Sudan, Eretria and Rwanda. In addition, the region is host to around 12.4 million internally displaced persons.

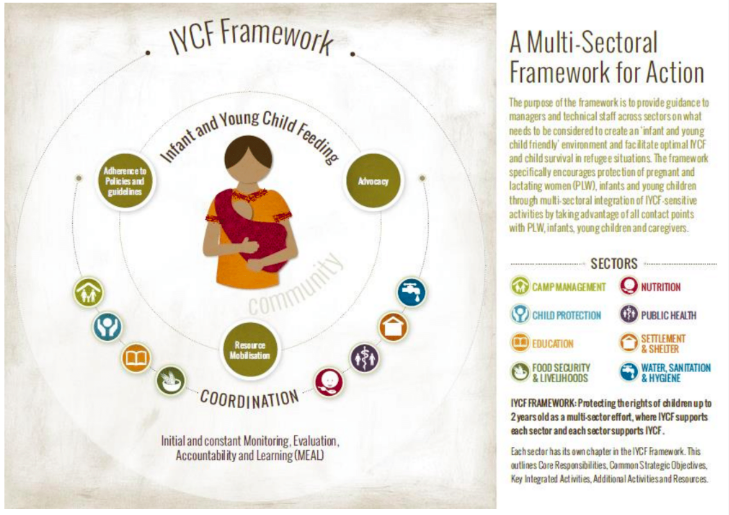

Nutrition and food insecurity remain key concerns in the region as a result of ongoing conflict and insecurity, prolonged drought, and increased food prices; all exacerbated when people are forced to flee their homes either internally or across borders. UNHCR conducts standardised expanded nutrition surveys (SENS)2 regularly throughout the region. Global acute malnutrition (GAM) levels among refugee populations in the region are typically high; in 2017/18, around 46/74 sites (62%) met the UNHCR GAM standards of <10%, while 15/74 (20%) of sites were above the emergency threshold of ≥15%. However, UNHCR surveys for 10 countries (Burundi, Djibouti, Eretria, Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, South Sudan, Tanzania, Rwanda and Uganda) from 2017/18 demonstrate considerable improvement in key nutrition indicators (including stunting in children and anaemia in children and women of reproductive age) compared to 2015/16 (Table 1). Improvements are due to strengthened nutrition screening (active case-finding among newly arrived refugees); improved nutrition monitoring and assessment; development and roll-out of UNHCR multi-sector IYCF framework for action (2017/18); training and capacity-building of UNHCR and partners on prevention and management of malnutrition; strengthening of preventative interventions; and strengthened partnership and collaboration at regional and country levels between WFP, UNICEF, WHO and FAO, including a regional UNHCR/WFP workplan and a UNHCR and UNICEF regional collaboration framework.

Table 1: Percentage of UNHCR refugee sites meeting targets and thresholds in EHAGL region 2015/2016 compared to 2017/2018

UNHCR’s approach to acute malnutrition management

Prevention, detection, referral and treatment of acute malnutrition are key elements of UNHCR’s global public health nutrition programme. This involves community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM); the protection, promotion and support of IYCF (Box 1); and multi-sector activities (Box 2 and Figure 2). Strong linkages and referral mechanisms exist between each element of CMAM, as well as with other interventions (healthcare, antenatal care, postnatal care and expanded programme of immunisations, with referral to district and regional hospitals where needed).

UNHCR works in close collaboration with existing national health and nutrition programmes in refugee-hosting communities in the region. To treat malnutrition, UNHCR provides services in refugee camps or through national programmes, depending on the context; always using the principles of CMAM and according to relevant national guidelines or WHO guidance where these do not exist.

Figure 1: Refugees and asylum seekers in EHAGL region

Figure 2: Nutrition Programme organogram in the refugee operation EHAGL region

In partnership with UNICEF, WFP, WHO and the national MoH, UNHCR conducts regular technical training and coaching sessions to build the capacity of health and nutrition personnel in the national health system and among UNHCR partners. Training commonly includes nutrition in emergencies, IYCF in emergencies, the multi-sector IYCF framework for action, and CMAM. Joint supportive supervision (UNHCR/UNICEF/WFP/project partners and MOH) is conducted in several refugee operations in the region (including Uganda, Ethiopia and Kenya).

All UNHCR-supported public health nutrition programmes are planned, assessed, monitored and evaluated using available quality health and nutrition data, collected and interpreted according to UNHCR guidance.3 UNHCR’s health information system (HIS) is currently available in two versions – one for camps and another one for out-of-camp (urban and rural) settings. The HIS is used to collect standardised health information from partners and to compile mortality data to help design, monitor and evaluate programmes in order to provide evidence-based information for programme monitoring and policy formulation.

Box 1: Multi-sector IYCF framework for action in refugee populations

UNHCR’s ‘Multi-sectoral IYCF framework for action in refugee populations’, rolled out in the region in December 2018 in priority countries (Uganda, Kenya, Sudan and Ethiopia), provides guidance to managers and technical staff across sectors on what needs to be considered to create an ‘infant and young child-friendly’ environment and facilitate optimal IYCF in refugee situations. The framework specifically encourages protection of pregnant and lactating women (PLW), infants and young children through multi-sector integration of IYCF-sensitive activities by taking advantage of all contact points with PLW, infants, young children and caregivers.

Box 2: UNHCR nutrition programme interventions

Preventative interventions:

- Community-based outreach programme through a network of outreach workers and volunteers, including: nutrition screening, detection and referral (‘active case-finding’); community sensitisation on prevention of all forms of malnutrition; supporting, promoting and protecting IYCF practices through awareness and mother-to-mother support groups; cooking demonstrations; and follow-up of SAM and MAM cases and PLW at community level.

- Growth monitoring and promotion in some refugee operations (depending on programme structure and resource availability).

- Preventive BSFP for children aged 6 to 23 months or 6 to 59 months and PLW (depending on context and available resources)

- Follow-up of cured cases from OTPs and provision of nutritional support to avoid relapse.

- Provision of nutritional support to HIV and TB cases (depending on context and available resources).

- Small-scale homestead gardening programme at household level (depending on context and available resources).

Curative interventions:

- TSFP for management of MAM cases using take-home dry rations.

- OTP for management of SAM cases without medical complications.

- Inpatient therapeutic feeding programme (SC based in the health facility) for management of SAM cases with medical complications.

Continuum of acute malnutrition care

Service delivery

UNHCR seeks to ensure a continuity of care for children who are acutely malnourished. This includes securing co-location of SC, OTP, TSFP and BSFP services and aligning systems to maximise efficiencies for those delivering services and the beneficiaries. Table 2 reflects the co-location of services achieved in the refugee settings in the region. UNHCR selects well-reputed international and national partners to implement preventive and curative nutrition interventions through project partnership agreements (PPAs). Partner selection considers sector expertise, programme experience, local knowledge, good relations with communities and track record of efficient and effective implementation. In almost all the refugee operations in this region, the management of SAM and MAM is under the responsibility of the one project partner. However, if more than one partner is involved, UNHCR makes sure that strong linkages and effective referral mechanisms are in place.

In accordance with the CRRF framework, wherever possible, UNHCR integrates nutrition and health programmes in the refugee population within existing health and nutrition programmes in refugee-hosting countries. An example of this is Uganda, where a national integrated health response plan for refugees and host communities has been developed and is being implemented.

Continuity of product supply

Given ongoing emergencies and new influxes of refugees in the region, contingency planning is an essential element of UNHCR operations and regional refugee response plans (RRRPs). As part of contingency planning and to cover supply pipeline breaks and sudden emergencies, UNHCR also sometimes directly procures contingency stocks of nutrition products (RUSF, RUTF) in refugee operations (e.g., in Dollo Ado and Gambella in Ethiopia, Kakuma and Dadaab in Kenya, and Uganda) and holds buffer stocks in some locations. In addition, UNHCR sometimes procures special nutritional products (such as RUSF and micronutrient powders (MNP)) to reduce micronutrients deficiencies and malnutrition in refugee populations (depending on the context and funding availability). The presence of RRRPs, country-level contingency planning and enhanced coordination among partners has prevented major breaks in the supply of RUSF and RUTF to refugee operations.

Information management

UNHCR has recently revised and upgraded its HIS to ‘Integrated Refugee Health Information System’ (IRHIS) to standardise data collection and analysis for all sector programmes (health, nutrition, HIV, reproductive health, expanded programme of immunisations (EPI)). For nutrition programming, information is now collected on each component, including MUAC screening, growth monitoring, SC, OTP, TSFP and BSFP using weekly tally sheets and monthly reports. Performance indicators include data segregated by sex and age groups, number of children screened, number of SAM and MAM cases identified and referred, new admission SAM and MAM, relapse cases, cured, defaulters, death, transfers, length of stay and weight gain for SAM and MAM cases. In partnership with its partners in the region, UNHCR is planning to pilot a project on digitalising individual nutrition records to help track and follow up children through different components in a nutrition programme (screening, referral/admission/discharge in and out from OTP, SC, TSFP and BSFP).

Table 2: UNHCR mapping of SAM and MAM treatment services in refugee operations 2017-2018

Challenges and constraints

Shortfalls in food and non-food assistance

Household food security is critical to prevent malnutrition and to support sustained recovery of treated cases. A major challenge to refugee operations in the EHAGL region is the increasing numbers of refugees in need and limited resources available to meet food and non-food needs. Due to funding shortfalls in 2018, UNHCR and WFP was unable to provide recommended food assistance (2,100 kcal/p/d) to refugees and adequate non-food assistance in the region, leading to serious cuts in refugee food rations in different counties in the region. The daily food basket was cut by 20-40% in Ethiopia; 50% for the old caseload of refugees in Uganda; 25% in Rwanda; 27% in Tanzania; 10-20% in Djibouti; 30% in South Sudan; and 30% in Kenya. There were also breaks in food distribution in Sudan. However, as a result of joint advocacy in 2019 and donor response, food assistance was restored to 100% in Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda. As evidenced in SENS surveys, food cuts have had a negative impact on the food security and nutrition situation of refugees, in the short term forcing them to use negative coping strategies to meet basic needs, such as missing or reducing meals; selling assets; taking loans with interest; child labour; and involvement in risky and harmful activities. In addition, UNHCR was unable to provide adequate supplies of non-food assistance which resulted in shortfalls in the supply of firewood for cooking, water containers and soap; reduced access of all households to latrines, and inadequate shelters in some of the refugee sites in the region. These factors increase the risk of protection-related issues among refugee women and children. Prolonged insufficient assistance will likely contribute to an increase in the prevalence of acute malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies among refugee populations.

Products for treatment of acute malnutrition

Problems with the supply chain can compromise the continuum of acute malnutrition treatment. There have been some challenges in the supply of nutrition products for SAM and MAM treatment and in preventative BSFP to the nutrition programme in several refugee operations. For example, due to insecurity and limited access to some of the refugee sites in South Sudan, there has been delay in the supply and delivery of nutrition products. In some countries in the region, limited capacity of the national nutrition programme supply chain has resulted in delays in the timely delivery of nutrition products requiring UNHCR intervention (e.g., in Ethiopia, UNHCR intervened to receive therapeutic feeding supplies in Addis Ababa and organised transportation to field locations in Gambella, Dollo Ado and other locations). Similar problems have been experienced in Djibouti, Eretria, Sudan, South Sudan, Rwanda and Uganda. In some instances, this is due to delayed and inadequate requisition for nutrition products from the nutrition programme in the district and sub-district to the national nutrition programme at the capital level. Funding gaps at the global and regional level have also compromised adequate supply and delivery of nutrition products for SAM and MAM treatment and preventive BSFP in the refugee population and host communities during 2019.

Health system and partner capacity

Delivering a continuum of treatment is compromised where the existing health system is inadequate, usually due to limited human resource, capacity, supplies of essential drugs, supervision and monitoring. UNHCR has ongoing challenges related to health system capacity in the region in both the country of origin of refugees (such as South Sudan, Somalia, DRC, Burundi, Sudan, Eritrea and Rwanda) and in countries of asylum (such as Uganda, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania and Djibouti). In some contexts where there is limited or zero presence of international non-governmental organisations, such as Eritrea, it is challenging to find a local partner with good capacity and resources.

Disease outbreaks emphasise the need for integrated or closely aligned health and nutrition services. Refugees are vulnerable to cholera and bloody diarrhoea in acute onset of emergencies. Outbreaks add pressure to ongoing health and nutrition interventions in refugee sites and refugee-hosting communities as caseload of morbidities increases, and complicate acute malnutrition management.

Limited access to national nutrition programmes

Challenges exist for the refugees who do not have access to national programmes where they exist, and for the nationals where services in host communities are absent. In some settings, the host government may not allow access to or integration of refugees into the national system. Regarding nationals, SAM cases from host communities surrounding refugee camps can easily access SC and OTP services within camps. However, there is often limited or zero possibility of further referral and follow-up for SAM cases that are discharged to the host community. In most refugee-hosting communities, there is limited or no treatment programme for MAM cases. A related challenge is limited nutrition screening for active case-finding and referral of acute malnourished cases at community level in refugee-hosting communities.

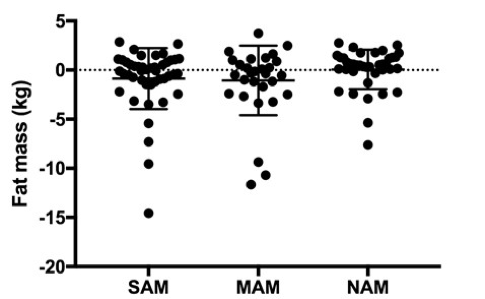

National guidelines variation in admission and discharge criteria

UNHCR and its project implementing partners apply standard nutrition guidelines for the detection, referral and treatment of SAM and MAM cases, including the use of WHZ (< -2SD) and MUAC (<125mm) as independent admission criteria. Results from the regional UNHCR SENS in 2017 (following standard criteria) indicated that, in around 84% of refugee sites, the prevalence of acute malnutrition was higher (two to four fold) based on WHZ (< -2 SD) criteria versus MUAC (<125mm); in 16% of surveys the converse was found. These results indicate the considerable proportion and number of children who meet WHZ criteria for treatment, most of whom would be excluded if MUAC only was used. Given this, UNHCR advocates and continues to use WHZ and MUAC as independent criteria for detection, referral and treatment of acute malnutrition, and programme planning in the refugee sites. However, in most of the countries in the region, only MUAC is recommended for screening detection and referral, according to the national nutrition guideline. This reduces enrolment coverage for SAM and MAM cases in nutrition programmes and raises concerns regarding missing treatment for most of the cases identified using WHZ only.

Discussion and conclusions

UNHCR’s experience in the region confirms a strong positive impact of interagency, multi-sector nutrition interventions on the overall health and nutritional wellbeing of refugees and other persons of concern. However, considering the very challenging context of this region, with acute and chronic humanitarian emergencies, huge need remains for continued and increased funding, technical support and partnership to ensure refugee and host community food and nutrition security. Enhanced, expanded, preventative and curative nutrition interventions, integrated and aligned to national systems where possible, are crucial. UNHCR’s experience underlines the importance of a multi-sector approach with a specific focus on protection, promotion and support of IYCF practices and treatment of acute malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies. UNHCR welcomes the opportunities created by the CRRF and GCR globally and in the region and seeks to expand collaboration to collectively work towards greater refugee inclusion in national social protection systems and improve refugee self-reliance.

In our experience, key enabling factors for a continuum of care for acute malnutrition treatment include:

- Coordination and collaboration among key UN agencies in the field of nutrition and food security for joint assessment, design/planning/implementation of interventions and monitoring and evaluation, with active involvement of MoH and national nutrition programmes.

- One implementing partner delivering on all acute malnutrition treatment programming.

- Linkages, referral mechanisms and integration of the nutrition programme with the existing healthcare programme should be considered from the start of programme design and carried through all phases of programme implementation.

- Support for training, capacity-building and coaching of health and nutrition personnel on management of all forms of malnutrition in the refugee-hosting communities.

- Harmonised data management to allow tracking of children through services.

- Involve and consult with the beneficiaries in all phases of implementation to ensure buy-in and sustainability.

Several areas of action are needed to improve on continuity of acute malnutrition treatment, including:

- Adequate and timely delivery and supply of nutritional products for prevention through BSFP and cure through TSFP, OTP and SC remains a challenge and needs attention and prioritisation. UNHCR may not be able to continue with direct procurement of nutrition products as contingency to fulfil the gaps in the supply and delivery; therefore this requires partner contribution.

- Given refugees dependency on food assistance and limited livelihood and agriculture opportunities, there is a strong need to continue provision of adequate food assistance to refugees, while working on better livelihood and agriculture programming. In situations where resources are limited, this requires prioritisation of refugees based on resources, as well as targeting food assistance based on needs.

- There is a strong need to continue interagency efforts in building the national health and nutrition system and capacity in the countries in this region (both in countries of origin and host countries).

- Strengthen regular joint supportive supervision and monitoring of nutrition interventions in the refugee sites/refugee-hosting communities.

- Standardisation and harmonisation of nutrition protocols in the different countries in the region is needed to align with standard WHO guidelines for management of acute malnutrition (use of WHZ and MUAC as independent criteria).

- Mainstream nutrition-sensitive interventions across other sectors (healthcare, WASH, livelihood/agriculture, education, child protection and community services) to help prevent malnutrition, increase self-reliance and reduce dependency on in-kind assistance.

For more information, please contact Naser Mohmand.

Endnotes

1https://intranet.unhcr.org/en/about/new-york-declaration.html

2www.sens.unhcr.org provides standard tools. SENS includes anthropometry as well as information on health, anaemia, IYCF, food security, WASH and mosquito net coverage.

3UNHCR’s global public health strategy/health information system.

References

The New York Declaration: the CRRF and the Global Compact on Refugees www.unhcr.org/the-global-compact-on-refugees.html

UNHCR global public health strategy: www.unhcr.org/protection/health/530f12d26/global-strategy-public-health-unhcr-strategy-2014-2018-public-health-hiv.html

UNHCR selective feeding guidelines: www.unhcr.org/publications/operations/4b7421fd20/guidelines-selective-feeding-management-malnutrition-emergencies.html

UNHCR Standardized Expanded Nutrition Survey (SENS) guidelines for refugee populations: http://sens.unhcr.org/

UNHCR IYCF framework for action: www.unhcr.org/5c0643d74.pdf