Regional overview of emergency nutrition preparedness in Latin America and the Caribbean

By Yvette Fautsch Macías and Stefano Fedele

Yvette Fautsch Macías is Nutrition Specialist at the UNICEF Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean (LACRO), where she has performed the role of GRIN-LAC Focal Point for the last two years.

Stefano Fedele is the former Regional Nutrition Specialist at UNICEF LACRO and the former coordinator of GRIN-LAC. He has been with UNICEF for the last 12 years. Before LACRO he led nutrition-sector coordination in Haiti, Sierra Leone, Mali, Chad and Afghanistan. He has been the Global Nutrition Cluster Coordinator since July 2019.

Location: Latin America and Caribbean (LAC)

What we know: Nutrition in emergency (NiE) preparedness can lead to a more rapid and cost-effective scaling up of emergency programming, thereby preventing malnutrition and saving lives.

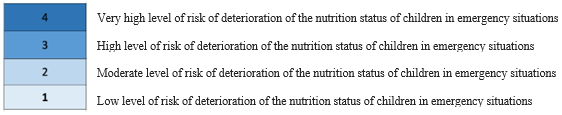

What this article adds: An NiE risk-assessment model was developed by GRIN-LAC, a regional coordination group for NiE. The 2019 model combines results of the existing Index for Risk Management for Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC-InfoRM) with six indicators of country nutrition capacity and four indicators of country nutrition vulnerability; namely child health and nutrition status. Data for 33 countries in the region were collected and, using newly developed risk indices and thresholds, country combined ‘nutrition in emergencies’ risk scores calculated. Results show that 27% of countries in the region are at high or very high risk of deteriorating population nutrition status in an emergency (with Haiti, Honduras, Guatemala and Venezuela at highest risk). Results show that 73% of countries have major gaps in nutrition capacity and 76% have high or very high levels of nutrition vulnerability (low rates of exclusive breastfeeding, poor minimum dietary diversity of complementary foods, high diarrhoea prevalence in children under five years old, and high rates of anaemia in children under five years old and women of reproductive age). There is an urgent need for LAC governments to strengthen nutrition-specific coordination mechanisms with a specific mandate in NiE; incorporate nutrition into national emergency-response plans; and strengthen optimal infant and young child feeding practices.

Background

The Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region is one of the most disaster-prone regions of the world, second only to Asia (Vargas, 2015). In 2017, an estimated 15.6 million people, including 8.2 million children, were affected by large-scale emergencies in the region (ECLAC, 2018). The average number of natural disasters affecting the LAC region more than tripled from an average of 19 each year in the 1960s to 68 each year in the 2000s. Now, approximately 13.4 million children and adolescents in LAC live in drought-prone or extremely drought-prone areas and 13.1 million live in areas at extreme risk of flooding (United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2015). The region is also vulnerable to political and economic shocks. In 2019, around 4 million people were estimated to have fled Venezuela into neighbouring countries and 1.1 million children were in need of assistance, including host children as well as migrant children, due to the increased demand on host systems and services (UNICEF, 2019). A lack of emergency nutrition preparedness exists in LAC countries due to a lack of a common understanding of the key elements required for effective emergency nutrition preparedness and response. Furthermore, nutrition has been deprioritised in the region in disaster response, due in part to declining levels of wasting and stunting.

Given this, a regional coordination group on nutrition was set up by UNICEF Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean in 2013, in collaboration with United Nations (UN) agencies, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), donors and research institutions at regional and national levels.1 The goal of GRIN-LAC (‘Grupo de Resiliencia Integral de Nutrición’) is to prevent the deterioration of the nutrition status of populations affected by crises in LAC by strengthening national capacities to prepare for and respond to issues related to NiE. Activities of GRIN-LAC include evidence generation; knowledge management, sharing and exchange; and capacity development. This article describes the process the GRIN-LAC undertook to develop a ‘Nutrition in Emergency Risk Assessment’ process and the results of the 2019 assessment of countries in the LAC region.

NiE risk-assessment model

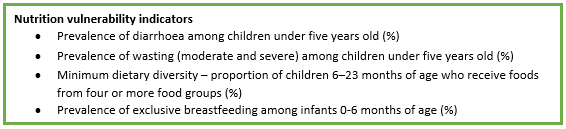

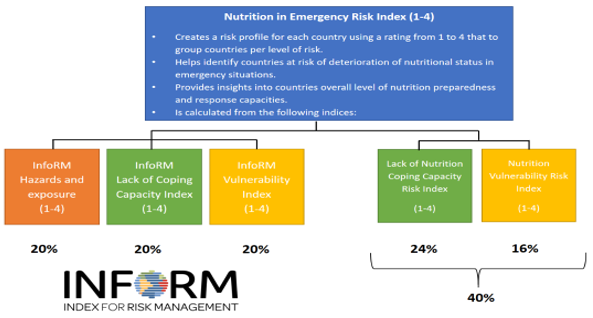

The Index for Risk Management for Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC-InfoRM) is a regional adaptation of the global InfoRM model (see Figure 1 and Box 1) used to assess the risk of humanitarian crises and disasters in all countries of the region. The InfoRM model was adapted to specific countries in Central America and the Dominican Republic. In order to assess the NiE risk more specifically, GRIN-LAC proposed a set of additional nutrition indicators representing minimum standards for emergency nutrition preparedness in LAC (Box 2). These were selected after discussion and agreement among group members. When combined with results of the LAC-InfoRM using an Excel file (the GRIN-LAC matrix2), these indicators produce an easy-to-interpret measure of NiE risk, identify gaps in nutrition preparedness, and highlight areas for improvement in policies, programmes and interventions to enable a stronger nutrition response in times of crisis. These indicators include six indicators of country nutrition capacities and four indicators of country nutrition vulnerability; namely the health and nutrition status of children (see Box 2). Nutrition indicators included in the ‘vulnerability risk index’ of the LAC-InfoRM 20193 were not included in the nutrition indicators as these were already accounted for.

During 2019, data were collected against each of the 10 indicators from 33 countries in the LAC region using national surveys, global databases and reports from national authorities. The process aimed to engage the National Nutrition Focal Points at the Ministries of Health (MoH) to generate awareness of nutrition-related risks, stimulate national-level discussions around nutrition capacity gaps and vulnerabilities, and prompt the development of national plans and strategies to address them.

Box 1: InfoRM (Index for Risk Management)

InfoRM is a global, open-source tool for assessing the risk of humanitarian crises and disasters.

It involves a composite index analysis that combines information about hazards, vulnerability and coping capacity. It aims to identify countries at risk of humanitarian emergencies and determine the major underlying conditions leading to the risk, so that these can be better managed. The InfoRM database combines around 80 different indicators that measure the following three dimensions:

Hazard and exposure risk index: captures events that could occur and the population that could potentially be exposed to those events. Hazards can be natural or human.

Lack of coping capacity risk index: captures the ability of a country to cope with an emergency in terms of institutional and infrastructure capacity.

Vulnerability risk index: captures the fragility of socioeconomic systems and the strengths of communities, households and individuals to confront a crisis situation. The index includes some nutrition indicators for vulnerable and uprooted groups, including stunting in children under five years old, low birth weight, and anaemia in pregnant and lactating women. These were included after GRIN-LAC advocated for their inclusion in 2017-2018.

Figure 1: LAC-InfoRM: The InfoRM for Latin America and the Caribbean

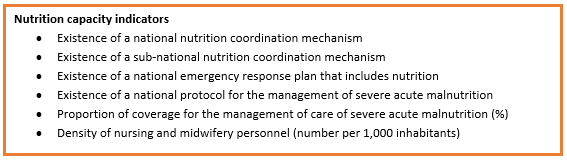

Box 2: Indicators representing minimum standards for emergency nutrition preparedness in LAC

Once collected, data was weighted according to the relative importance of each of the 10 indicators. A weighting of five was given to indicators that form the basis of emergency nutrition preparedness (national nutrition coordination capacity; national nutrition response plan; adequate infant and young child feeding practices). A weighting of four was given to elements that help to operationalise the basic elements (protocol for management of acute malnutrition and adequate number of healthcare professionals). A weighting of three was given to other elements, including existence of sub-national nutrition coordination capacity and coverage of management of acute malnutrition and vulnerability indicators (prevalence of diarrhoea and acute malnutrition). The sum of the weighted scores produced a lack of nutrition coping capacity score (sum of weighted nutrition capacity indicators) and a nutrition vulnerability score (sum of weighted nutrition vulnerability indicators) for each country.

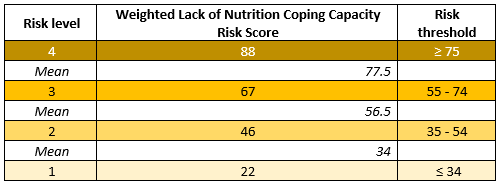

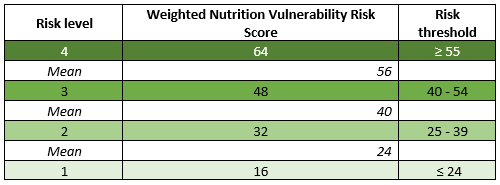

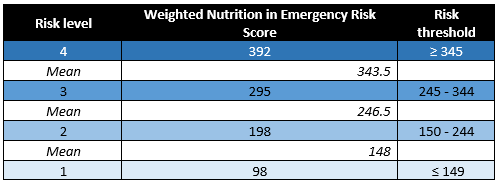

To determine levels of risk indicated by these scores, risk indices were developed for both dimensions (Tables 1a and 1b). Risk thresholds for each individual indicator were then set, the mean of which helped to guide thresholds of risk for each dimension (Table 2a and 2b).

Following this, the nutrition scores were combined with LAC-InfoRM scores to obtain an overall score for each country to indicate the level of emergency nutrition preparedness and risk of deterioration in nutrition status during an emergency (Figure 2). To interpret these scores, overall indices and risk thresholds were set using the same process (Tables 3 and 4).

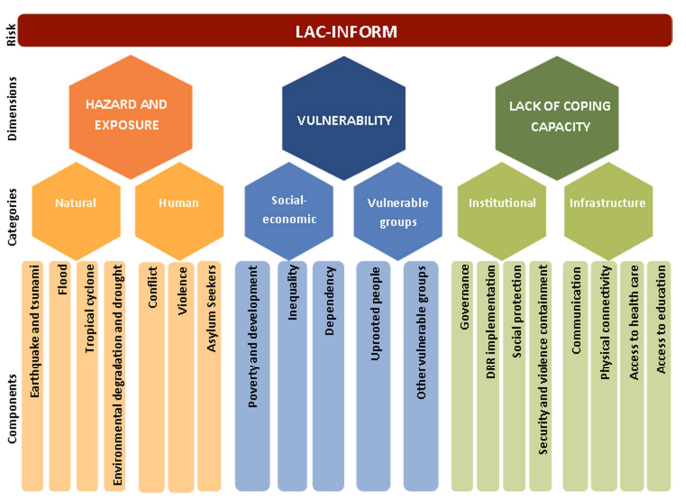

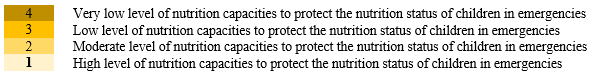

Table 1a: Lack of nutrition coping capacity risk index

This is estimated from each country’s lack of nutrition coping capacity score. It captures the ability of a given country to cope with an emergency in terms of coordination and institutional capacity around nutrition to protect the nutrition status of children in emergency situations.

Table 1b: Nutrition vulnerability risk index

Estimated from each country’s nutrition vulnerability score, this captures children’s food and nutrition characteristics of a given country that can deteriorate in emergency situations.

Table 2a: Thresholds for lack of nutrition coping capacity risk scores

Table 2b: Thresholds for nutrition vulnerability risk scores

Figure 2: NiE risk-assessment model

Table 3: NiE risk index

Table 4: Thresholds for overall NiE risk scores

Limitations of the model

The model has some limitations; therefore the results should be interpreted with caution. The selection of parameters to determine risks was a subjective process and changes in weights and thresholds may lead to different risk scores. Data for all nutrition capacity indicators, except the density of nursing and midwifery personnel, were obtained from direct reports from national authorities or UNICEF country offices. The subjective nature of these indicators means that the data is open to under or overestimation and may not always provide an accurate picture of the situation. Some countries do not collect data against some of the indicators included in the model. In these cases, the regional value of the indicator is inserted; or, when the regional value is not available, a score of four was used to calculate risk scores and indices. Lastly, some of the country-level data used were not up-to-date and may reflect the situation in years before 2019.

Results of the 2019 LAC NiE risk assessment

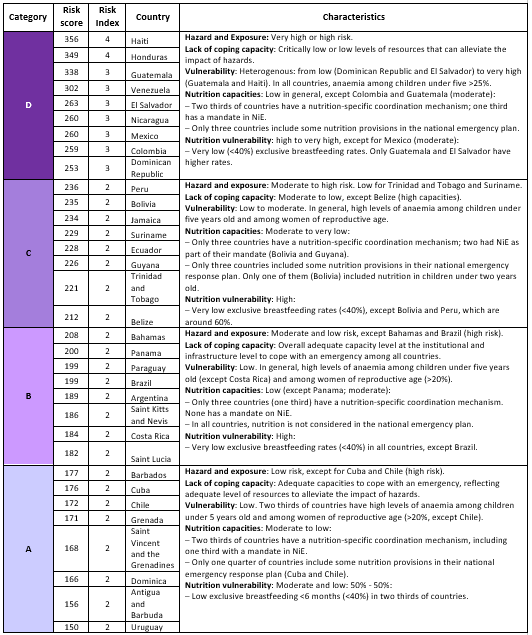

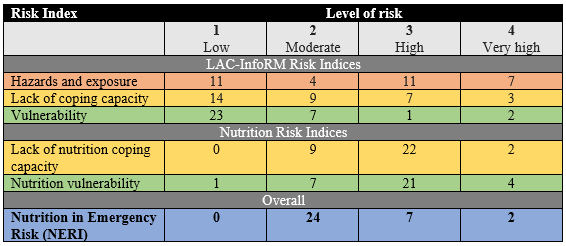

Based on data collected in the region, overall NiE risk-assessment scores were calculated and are presented in Table 5. This is the third time an NiE risk assessment was undertaken (previously conducted in 2016 and 2017). Countries were assigned to risk categories from highest to lowest risk, with characteristics of this level of risk described. Table 6 shows the number of countries grouped by risk index and level of risk.

Table 5: Level of nutrition risk in LAC countries

Table 6: Country grouping per risk index and level of risk

Twenty-seven per cent (9/33) of countries in the LAC region are at high or very high risk of deterioration of nutrition status if an emergency arises. Almost three quarters of countries (73%; 24/33) are at high or very high risk due to gaps in nutrition capacity. Key gaps identified across the region include capability of nutrition-specific coordination mechanisms at national and sub-national levels to identify and address nutrition-related vulnerabilities and capacity gaps; capability of nutrition plans to prevent and/or address nutrition problems of children under two years old; lack of updated protocols for the management of acute malnutrition; and insufficient capacity in the available health workforce to respond in a crisis.

Results show that over three quarters of countries in the LAC region (76%; 25/33) have high or very high levels of nutrition vulnerability, explained by low rates of exclusive breastfeeding among children under six months of age; poor minimum dietary diversity of complementary foods among children age 6-23 months, ranging from 29.2% (Haiti) to 90.4% (Peru); and diarrhoea prevalence among children under five years old higher than 13% in one quarter of countries (27%). Wasting appears to be less of a problem, with prevalence lower than 4% in approximately 85% of countries (28/33), ranging from 0.3% (Chile) to 6.8% (Barbados).

The 2019 LAC InfoRM vulnerability risk index shows that anaemia among children under five years and women of reproductive age are important concerns. In total, 85% countries have rates of anaemia among children under five years of over 20%, and in 91% countries, 15% (or more) of women of reproductive age are currently anaemic. In terms of low birth weight and stunting, most countries (30/33; 91%) have low birth weight rates of less than 12% and almost two thirds of countries (22/33; 67%) have stunting rates lower than 10%.

Discussion and next steps

The NiE risk assessment has provided a much-needed overview of the emergency nutrition preparedness situation in the LAC region. Results show that, while many countries have some degree of emergency nutrition preparedness in place, no country demonstrates optimal capacity. Results provide a clear call for greater action to identify capacity gaps and vulnerabilities at country level and develop policies, plans, programmes and interventions to address them. Compared to previous years (2016 and 2019), some improvements have been made at country level, but limited nutrition human resources and budgetary constraints were cited as main barriers to the development of policies, plans and strategies to improve country-level preparedness.

The following actions are suggested by GRIN-LAC to strengthen the most important elements that form the basis of emergency nutrition preparedness in the region:

- Establish or strengthen national and sub-national nutrition-specific coordination mechanisms, including the participation of government and non-governmental institutions, humanitarian groups and bilateral and multilateral partners, with a specific mandate in NiE.

- Incorporate nutrition in national emergency response plans by linking nutrition actors and services to disaster-management agencies at national, sub-national and community level, developing national guidelines on infant and young child feeding in emergencies and developing a contingency plan in nutrition, including the prepositioning of supplies; e.g., multiple micronutrient powders, micronutrient supplements for pregnant and lactating women, oral rehydration salts, fortified nutrition products and anthropometric equipment.

- Establish/strengthen policies and strategies to promote optimal infant and young child feeding practices.

Some countries have already acted to improve their NiE preparedness with the support of GRIN-LAC. In 2016, GRIN-LAC, together with UNICEF Nicaragua, supported the Nicaraguan government to conduct a national NiE risk assessment. Results were presented to the Health Commission of the National System for Disaster Prevention, Mitigation and Attention, and guidelines for NiE were subsequently developed by the Ministry of Health (MoH) with technical and financial assistance from UNICEF and in collaboration with other actors at national and local level. The process ensured broad ownership and application by multiple relevant government bodies and organisations. An NiE national coordination mechanism (GRIN-RD) was also established in the Dominican Republic in 2017 to coordinate the food and nutrition response in emergency situations. In 2019, support was provided by GRIN-LAC to GRIN-RD to strengthen the functioning of the group through a four-day workshop on leadership and coordination, resulting in an 18-month work plan detailing subsequent actions to be taken.

A similar process was followed by Guyana’s Nutrition Focal Point at the MoH. After discussions with GRIN-LAC on country nutrition capacities and vulnerabilities, establishment of a nutrition coordination group was identified as a first step in emergency nutrition preparedness. The MoH drafted Terms of Reference for this national mechanism and hosted a one-day stakeholders’ meeting in 2018 to chart the way forward for the establishment of the nutrition coordinating body, beginning by clarifying roles and responsibilities of various agencies. This body became operational in 2019.

Conclusion

GRIN-LAC is a regional NiE mechanism that can assist countries to minimise vulnerabilities and increase coping capacities for improved emergency nutrition preparedness and strengthen resilience. Enhanced methods to assess NiE risks in the region have resulted in a valuable measure of the nutrition capacity gaps and vulnerabilities that exist at country level. Results of the 2019 assessment suggest that, although there is variation both in terms of NiE capacity and vulnerability across the region, significant gaps persist in most countries. Urgent action must be taken to raise nutrition on national agendas and to strengthen sector coordination, early planning and mobilisation of capacities and resources to improve preparedness and response capacity, and enhance resilience to recurrent shocks.

For more information, please contact Yvette Fautsch MacÃas at yfautsch@unicef.org

References

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), United Nations Children’s Fund, Latin America and the Caribbean 30 years after the adoption of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (LC/TS.2018/21), ECLAC/UNICEF, Santiago, 2018.

UNICEF, Unless we Act Now: The impact of climate change on children, UNICEF, New York, 2015.

UNICEF, Migration flows in Latin America and the Caribbean - Situation Report No.8, UNICEF, September-October 2019.

UNICEF, Preparedness for Emergency Response in UNICEF - Guidance Note 2016, UNICEF, New York, USA, December 2016.

1 PAHO/WHO, WFP, FAO, Care, the International Federation of Red Cross, Save the Children, ACF, Plan International, INCAP and others.

3 Anaemia in women of reproductive age, low birth weight, anaemia among children under 5 years old, stunting among children under 5 years old.