Coordination of the Nutrition Sector response for forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh

By Abigael Naliaka Nyukuri

Abigael Naliaka Nyukuri worked for United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Bangladesh as the National Nutrition Cluster Coordinator between 2017 and 2019 and is currently working for UNICEF Nigeria as Nutrition Specialist in the Northeast Humanitarian Response. She has over 10 years of experience working as a nutrition specialist in complex humanitarian contexts in Kenya, South Sudan, Somalia, Bangladesh, Philippines, Mozambique and Nigeria.

The author would like to acknowledge the considerable input and support given in the writing of this article by Ingo Neu, former Cox’s Bazar Nutrition Sector Coordinator, UNICEF, Henry Sebuliba, former Cox’s Bazar Nutrition Sector Coordinator and later Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) Specialist, UNICEF and Caroline Wilkinson, Senior Nutrition Officer, United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR).

Location: Bangladesh

What we know: Bangladesh is highly vulnerable to recurrent natural disasters. A national preparedness cluster system exists to support government response to slow and sudden-onset emergencies.

What this article adds: In August 2017, 800,000 forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals (FDMNs) arrived in Cox’s Bazar (CXB) district in Bangladesh. The speed, scale and nature of the humanitarian crisis exceeded national capacity and a hybrid coordination system was adopted to coordinate the FDMN response. This was initially supported by the existing National Nutrition Cluster (NNC) until a dedicated Nutrition Sector Coordinator was recruited for CXB. Successful technical coordination included negotiated continued use of therapeutic foods for the treatment of acute malnutrition in the FDMN response. Complexities that fragmented the nutrition response included a lack of clarity over the United Nations coordination mandates, given the unique FDMN context, a challenging operational environment, overwhelming urgent demand, lack of nutrition capacity in health services, and low investment in and accountability for inter-sector coordination. The existence of robust disaster management regulatory and policy framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) at country level is instrumental in informing and coordinating governments’ efforts in humanitarian response. Response coordination models for challenging scenarios should be examined and appropriate global guidance/coordination mechanisms developed, with necessary inter-United Nations memoranda of understanding formalised at regional and country levels. Preparedness measures and technical, operational and managerial capacity-building initiatives require institutionalisation at multiple levels.

This article complements a second article that examines programming experiences around continuity of care for acute malnutrition management in more detail, soon to appear in Field Exchange online (https://www.ennonline.net/fex)

Background

Bangladesh has a population of approximately 165 million people, with a dense coastal population and a geography dominated by flood plains. The country is highly vulnerable to a range of recurrent natural disasters and is ranked fifth globally on climate vulnerability.1 Although there has been significant progress in tackling undernutrition in recent years, an estimated 31% of children below five years of age remain stunted, 8% are wasted and 22% are underweight.2 Cox’s Bazar district, which has a population of 2.7 million people (39.7% of whom are children), is one of the worst performing districts in almost all child-related and gender inequality indicators and one of the most vulnerable to disasters and climate change in Bangladesh.

Access to adequate nutrition as a basic human right is enshrined in the Constitution of the Government of Bangladesh (GoB). The National Nutrition Policy (NNP), endorsed in October 2015, provides direction for the implementation and strengthening of strategies and actions to improve the nutritional status of the population. The National Plan of Action for Nutrition (NPAN2) details priority strategic actions to put this policy into practice for the 2016-2025 period. It includes a strong social behaviour change communication (SBCC) agenda, research and capacity-building. The NPAN2 aims to reduce wasting prevalence to 8% and stunting prevalence to 25% by 2025 through a multi-sector approach and by treating wasting at scale through health facilities and within the community.

National and sub-national coordination mechanisms for disaster risk reduction in Bangladesh

The GoB has a strong disaster management regulatory framework3 due to the country’s vulnerability to climate change. The GoB has formulated and enacted disaster management acts, policies, plans, standing orders and an appropriate institutional framework for implementation. Detailed roles, responsibilities and actions of committees, ministries and partner organisations required for implementing Bangladesh’s disaster management model are clearly outlined, with the aim of reducing the vulnerability of people, especially the poor, to the effects of natural, environmental and human-induced hazards to a manageable and acceptable humanitarian level. The GoB, United Nations (UN) agencies, the World Bank and international and local non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have worked for decades to prepare for disasters and mitigate the effects of climate change.

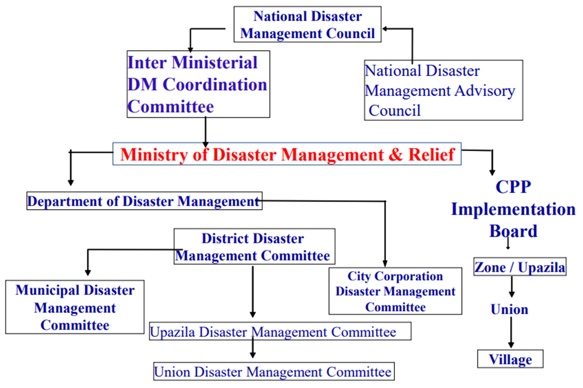

There are three national-level government disaster response coordination forums that sit under the Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief (MoDMR), as shown in Figure 1. The National Disaster Management Council (NDMC) is responsible for strategic decisions for disaster management; the Inter-Ministerial Disaster Management Coordination Committee (IMDMC) is responsible for coordination across ministries; and the National Disaster Management Advisory Committee (NDMAC) is responsible for policy development and advice. The NDMC is the highest-level decision-making body for disaster management in Bangladesh. At sub-national levels, Disaster Management Committees (DMCs) have been constituted for the smallest geographical area (upazila) to lead regional-level disaster risk reduction efforts. The Cyclone Preparedness Plan (CPP) Implementation Board, headed by the Secretary of the Ministry of Food and Disaster Management, provides implementation and administrative support to strengthen collective preparedness and response for cyclones in prone districts.

Figure 1: National and sub-national coordination mechanisms for disaster risk reduction in Bangladesh

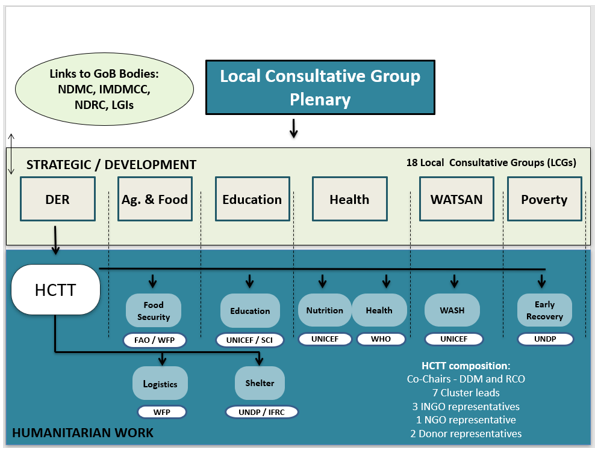

Following lessons learned from the emergency response to Cyclone Sidr in 2007, which claimed over 3,000 lives in the southwest coast region of the country, in 2012 the GoB Local Consultative Group on Disaster and Emergency Response (LCG DER) under the MoDMR endorsed the rollout of a modified national cluster system4 (i.e., not mandated by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC)) and creation of a Humanitarian Coordination Task Team (HCTT) (see Box 1). This modified cluster system was developed to enable a more coherent, coordinated and effective multi-agency, multi-sector humanitarian response to both slow and sudden-onset crises. The HCTT, which sits under the LCG DER, is a coordination platform to strengthen the collective capacity of government, national and international actors to ensure effective humanitarian preparedness for, response to, and recovery from disasters in Bangladesh. The HCTT acts as an advisory group to the DER, providing advice, implementing agreed actions and feeding back to the wider LCG DER group. The team also acts as a coordination platform for nine government-mandated thematic clusters in Bangladesh (nutrition; health, food security; water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH); education; logistics; child protection; shelter and early recovery) under the overall coordination responsibility of the MoDMR, with joint needs assessments and planning (Figure 2). The development and functions of the National Nutrition Cluster (NNC) are described in Box 1.

Figure 2: National Cluster architecture in Bangladesh

NDMC = National Disaster Management Council; IMDMCC = Inter-ministerial Disaster Management Coordination Committee; NDRC = National Disaster Response Coordination Group; LGIs = Local Government Institutions; DER = Disaster and Emergency Response; WATSAN = Water, Sanitation and Hygiene; HCTT = Humanitarian Coordination Task Team; FAO = Food and Agriculture Organization; WFP = World Food Programme; UNICEF = United Nations Children’s Fund; SCI = Save the Children International; WHO = World Health Organization; UNDP = United Nations Development Programme; IFRC = International Federation of the Red Cross; DDM = Department of Disaster Management; RCO = Resident Coordinator’s Office; INGO = international non-governmental organisation; NGO = non-governmental organisation

Box 1: National Nutrition Cluster in Bangladesh

In 2012 the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) Local Consultative Group on Disaster and Emergency Response (LCG DER) officially endorsed the establishment of a government-mandated (non-IASC) National Nutrition Cluster (NNC) in Bangladesh as part of the modified national cluster system. The NNC aims to strengthen the nutrition capacity of the government and LCG DER to prepare for and respond to slow and sudden-onset emergencies in Bangladesh, mainly focused on natural disasters. During non-emergency periods the NNC supports the development of contingency plans that include minimum preparedness actions (MPAs) (for risks profiled as having low and medium likelihood and impact) and advanced preparedness actions (for risks profiled as having high likelihood and impact). MPAs are to be undertaken by government (in the context of development programmes) and humanitarian actors to support a coordinated, timely and quality response to crises.

The NNC is co-chaired by the Institute of Public Health Nutrition (IPHN) under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Both actors share equal responsibilities and work together in partnership as co-leads, with the head of IPHN providing leadership within the government and UNICEF providing support for cluster leadership as per its global mandate, with support from the Global Nutrition Cluster (GNC). UNICEF also provides the NNC with a Nutrition Cluster Coordinator (NCC) and Information Management Officer (IMO).

The NNC, similar to the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC)-mandated clusters, works to achieve six core functions: supporting service delivery; informing strategic decisions of the Humanitarian Coordinator (HC) and Humanitarian Coordination Task Team (HCTT); planning and implementing cluster strategies; monitoring and evaluating performance; building national capacity in preparedness and contingency planning; and advocacy and accountability to affected populations as a cross-cutting theme.

A separate Nutrition Working Group at national level focuses on developmental aspects of nutrition in Bangladesh. The common understanding is that, in the event of a level 3 emergency, where in-country capacities are exceeded, the NCC will transition to an activated IASC Cluster. Due to the unique nature of the legal status of FDMNs in Bangladesh, the NNC was not activated in response to the Rohingya crisis; however, the national preparedness plans and experiences were used to establish and inform sector coordination and response in Cox’s Bazar.

History of the displacement of Rohingya people

The Rohingya people have experienced decades of discrimination, statelessness and targeted violence in Rakhine State, Myanmar. This has forced thousands of Rohingya people over the border from Myanmar into Bangladesh since the early 1970s. Two official refugee camps, Kutupalong and Nayapara, were in existence prior to 2016 and home to around 30,000 Rohingyas with official refugee status. Many more unregistered Rohingya people lived in Kutupalong and Leda makeshift camps/sites. The end of 2016 and early 2017 saw an influx of around 70,000 Rohingyas, initially referred to as Undocumented Myanmar Nationals (UMNs). This group received humanitarian assistance from the GoB, UN agencies (including UNHCR) and NGOs under the overall coordination of the GoB and the International Organization for Migration (IOM).5 In August 2017, attacks on police posts and the subsequent backlash in northern Rakhine resulted in a sudden mass influx of approximately 800,000 Rohingya people (over half of whom were children), known by this time as Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals (FDMNs),6 into Cox’s Bazar (CXB), tripling the number of displaced people in that district in just over two weeks. This resulted in one of the largest displaced settlements in the world. Arriving FDMNs spontaneously settled in makeshift camps as each family/household established a shelter wherever it could (see Figure 3). The entire infrastructure and basic services for the Rohingya population had to be established quickly to provide much-needed life-saving interventions. This was made all the more complex by the fact that a large section of the settlement area had a hilly terrain and was heavily forested.

Coordination surge to Rohingya crisis in 2017

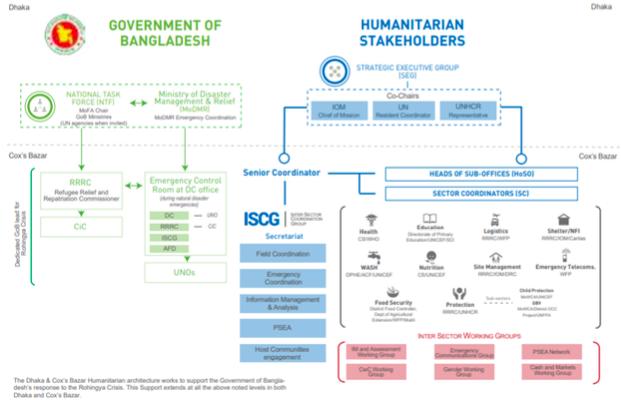

Despite having strong preparedness mechanisms in-country, the GoB’s capacity to effectively respond to the huge influx of FDMNs in 2017 was exceeded due to the speed, scale and nature of the crisis. Due to the pre-existence of an emergency coordination mechanism, a hybrid system was adopted to coordinate the FDNM response. The humanitarian response was and continues to be led and coordinated by the existing GoB National Task Force (NTF), which is chaired by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and includes 29 ministries and entities. Following the population influx, the existing Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner (RRRC), under the MoDMR (which was previously involved in supporting both registered refugees and non-registered Rohingyas in Kutupalong and Leda makeshift camps) was mandated to provide operational coordination for all refugees/FDMNs. At the request of the relevant government authority, international humanitarian responders acted to complement and support GoB efforts, creating a hybrid humanitarian coordination system.

Strategic guidance and national-level government engagement for humanitarian agencies is provided in this system by a Strategic Executive Group (SEG) in Dhaka (see Figure 3), co-chaired by the Resident Coordinator, the IOM and UNHCR. UNHCR and IOM were nominated for this role due to their large presence in CXB pre-crisis and experience in providing humanitarian assistance over many years for both the registered and unregistered Rohingya populations. At district-level, the Senior Coordinator leads the Inter-Sector Coordination Group (ISCG), which is composed of thematic Sector and Working Group Coordinators who represent the humanitarian community, ensuring coordination with the RRRC and the District Commissioner (DC) (including Upazila Nirbahi Officers (UNO) at the upazila (sub-district) level). Regular coordination meetings are held at upazila level to facilitate coordination, co-chaired by UNOs and the ISCG (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Rohingya disaster response coordination mechanism

Nutrition coordination in the Rohingya response

Nutrition Sector coordination mechanism

As part of this hybrid system and as agreed under existing minimum preparedness actions (MPAs), the NNC established the Nutrition Sector as a dedicated coordination mechanism specifically for FDMNs in CXB in response to the crisis. In the initial phase, the UNICEF-employed NNC Coordinator also acted as Nutrition Sector Coordinator until someone could be appointed to this post. Once this post was recruited, the NNC Coordinator transitioned their role to the scale-up of UNICEF’s programmatic response in CXB for three months until dedicated capacity was recruited, in addition to the NNC Coordinator function. This was challenging, given the vast coordination needs of the FDMN response, as well as growing programming needs of the UNICEF response in addition to the needs of the NNC coordinator function. Even after a Nutrition Sector Coordinator (NSC) was recruited, high staff turnover in this role contributed to ongoing coordination challenges in the initial months of the crisis.

The Nutrition Sector response was guided by the 2017 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) and detailed Nutrition Sector response strategy, which was developed collectively by Nutrition Sector partners and endorsed by an ad hoc sector advisory group. A formalised Nutrition Sector Strategic Advisory Group (SAG) was finalised in late 2017.7 The detailed Nutrition Sector response strategy provides operational and technical guidance for the response and is continually updated according to emerging evidence and current global guidance. In March 2018, the HRP transitioned to the Joint Response Plan (JRP)8 which provided strategic guidance for a coordinated response to address the immediate needs of the refugees, FDMNs and mitigate the impacts on affected surrounding host communities. The JRP incorporated funding and participation from the private sector.

In Kutupalong and Nayapara camps, where Myanmar nationals had received official refugee status, UNHCR continued to play a coordinating role and nutrition services were provided through a tripartite agreement between UNHCR, World Food Programme (WFP) and Action Contre La Faim (ACF). Outside these camps, WFP and ACF provided nutrition services.

Office of the Civil Surgeon

The Office of the Civil Surgeon (CS Office), under the MoHFW, is the government entity that oversees all health and nutrition activities in CXB district. The CS Office, together with UNICEF as the Nutrition Sector/Cluster lead agency, led the collective nutrition response and co-chaired Nutrition Sector meetings from the onset of the crisis. The CS Office works closely with the Institute of Public Health Nutrition (IPHN) (see below) to authorise and approve guidance, the Nutrition Sector response strategy and assessments and surveys planned and conducted by Nutrition Sector partners. Due to the massive scale of the health and nutrition response, the CS Office required additional human resources to lead and coordinate both the health and nutrition responses effectively. It proved challenging to recruit sufficiently qualified and dedicated personnel to be seconded to and stationed in the CS Office in CXB to support the SAG in strategic decision making, development of technical guidance for nutrition, and sector coordination. This was mainly due to the fact that IPHN, the technical nutrition department for MoHFW, is a centralised department, with no dedicated presence at district level.

Institute of Public Health Nutrition (IPHN)

The IPHN, located in Dhaka, is the national department responsible for providing technical guidance on nutrition and co-chairs the NNC with UNICEF. The IPHN, through the CS Office, provides technical and strategic guidance for the Rohingya response and supports linkages between the NNC and Nutrition Sector. This ensures that the collective response is in line with GoB policies, guidelines and standards and that guidance for the response is informed by emerging evidence. For example, the IPHN led advocacy to high-level government offices for the continued use of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) and the use of ready-to-use supplementary food (RUSF) for the treatment of wasting as part of the ongoing Rohingya response. RUTF had been used in treatment of wasting in registered and unregistered refugees for several years (via UNHCR and several NGOs), but RUTF and RUSF are not routinely used in acute malnutrition management in Bangladesh. Advocacy was needed for the endorsement of their use as a continuing part of the Rohingya response, building on existing NGO-led prevention and treatment programmes, drawing on evidence generated by Nutrition Sector partners to do so.9

The IPHN also leads specific activities, such as the Nutrition Action Week (NAW) held in November 2017 when all children aged 6-59 months in registered refugee camps and makeshift settlements were screened for wasting (and identified cases referred for treatment) and provided with deworming and vitamin A supplementation. In the later part of the response, a liaison officer, a former IPHN senior staff member, was recruited by UNICEF and seconded to the CS Office as part of the Nutrition Sector Coordination team. This further strengthened links between the CS and IPHN as well as between the Nutrition Cluster and Nutrition Sector.

Contextualised guidance

The rapid scale-up of community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) services for FDMNs in the response was greatly helped by the pre-existence of contextualised guidelines for CMAM used in the official camps in the Rohingya response pre-August 2017 (using RUTF, with mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) as an independent criterion and both community and facility-based management of severe acute malnutrition (SAM)). Pre-existing SAM treatment services run by ACF and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in the registered and makeshift camps absorbed many of the severely malnourished children in the first weeks of the crisis, before the large scale-up of services to a wider geographical area. Authorisation from IPHN/MoH for the use of RUTF and RUSF specifically for the Rohingya population residing in the makeshift camps was facilitated by agreements that already existed through the RRRC and MoDMR. The wider use of RUTF and RUSF was advocated for by UNICEF, WFP, the IPHN and NNC, justified by poor access to adequate and nutritionally diverse foods in the makeshift camps. Eventually, sections of the national guidelines were contextualised to suit the Rohingya context, with the approval of the CS Office and IPHN. In addition, anthropometric admission criteria were officially expanded to include MUAC in addition to weight-for-height z-score to reflect practice on the ground

Multi-sector coordination

At national level, integration points between key sectors (Nutrition; Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH); Food Security and Health) had been agreed and were reflected in national multi-cluster contingency plans/MPAs, coordinated by the HCTT. Consensus was reached on an integration strategy between the Nutrition, WASH and Food Security Sectors in CXB at the outset of the response and were endorsed at a meeting of the Heads of Sub Office (HoSO).10 However, effective uptake of the strategy was constrained for several reasons. Limited funding for inter-sector activities meant each sector could only prioritise sector-specific activities, while high staff turnover and lack of dedicated ‘inter-sector’ personnel meant there was limited technical capacity to support integration efforts. Other challenges included space constraints and population movement in the makeshift settlements, which made the integration of activities difficult to implement in practice.

Progress was made on coordination between the Food Security Sector (FSS) and Nutrition Sector following initial challenges and weak programme alignment. The blanket supplementary feeding programme (BSFP) was managed under the FSS for the first six months of the response, while the targeted supplementary feeding programme (TSFP) was managed under the Nutrition Sector. Children aged 6-59 months received similar services and the same product (CSB++) under both TSFP and BSFP, making it difficult to distinguish between beneficiaries of the two interventions. In practice, most children were reported under the BSFP, which meant coverage of the TSFP was underestimated. At the same time, a few partners reported BSFP recipients to the Nutrition Sector, which added to the confusion. To address this, the BSFP was relocated under the Nutrition Sector and, after a period of transition, referral mechanisms between TSFPs and BSFP were strengthened through both community outreach and facility-based growth monitoring platforms. Discussions on the food basket for the general food distribution programme (GFD) between the FSS and Nutrition Sector partners also led to development of a more nutritionally diverse food basket that provided adequate calories. Despite the GFD having very good coverage, access to adequate and appropriate complementary food for children aged 6-24 months was a challenge at the beginning of the response. This was somewhat improved by the transitioning of the GFD to a food voucher programme one year after the onset of the response.

Reflections on lessons learned

The FDMN response was dynamic from the outset, given the unique context of a hybrid coordination mechanism grounded in emergency preparedness. The response provides a strong example of government-led coordination and leadership in close collaboration with humanitarian stakeholders with an IASC Cluster model adapted to suit the specific context. It reflects strong government commitment to preparedness, including heavy investment in devolved (sub-national/district) coordination mechanisms. Considerable structures and frameworks were already in place pre-crisis, with agreed MPAs and Advanced Preparedness Actions (APAs). However, given previous country experiences, the preparedness system was primarily centred on natural disaster response. This meant the modus operandi did not necessarily suit a mass population influx and ‘real time’ innovation was required to provide suitable coordination. This experience provides rich learning for Bangladesh and other similar contexts. With this in mind, some further reflections are shared here.

UN institutional arrangements

The ‘triple-hatting’ of the NNC Coordinator during the establishing of the Nutrition Sector coordination mechanism was feasible in the preparedness phase, but proved impossible to sustain following the huge surge in demand for nutrition services, necessitating a dedicated coordinator for CXB. An overstretched NNC Coordinator and high staff turnover in the early days; significant complexities regarding UN coordination arrangements, whereby UNHCR did not have the same overall authority that it does in ‘usual’ refugee contexts; a difficult operational environment (camp congestion and limited space); lack of nutrition capacity within the health system (most Health Sector partners do not provide any nutrition services); and prioritisation of life-saving/immediate needs in the early response resulted in a fragmented nutrition response. Nutrition services were established in line with respective UN agency mandates and were poorly aligned. This resulted in poor continuum of care between malnutrition treatment services for SAM (UNICEF-led) and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) (WFP-led) and weak linkages with nutrition services, specifically BSFP (WFP-led).11

Prior to and after the crisis, District Disaster Management Committees (DDMCs) were responsible for district-wide emergency planning and response. However, nutrition was often deprioritised in discussions and resource allocation, despite DDMCs members having received nutrition in emergency trainings. A liaison officer seconded to the CS Office proved a valuable addition to support coordination; however, there were practical challenges in securing this position, including the lengthy process of identifying and endorsing a suitable person by the IPHN due to the need for the person to be based in CXB (which most candidates were reluctant to accept), have good experience and a command of GoB health and nutrition policies, guidance and standards.

Humanitarian-development nexus

This response provides practical examples of how to connect humanitarian and development actions in terms of programming and guidance. For example, through its development programme, UNICEF procured and pre-positioned supplies in government Central Medical Stores for treatment of 10,000 children with SAM during the emergency response. The NNC also supported the further development of national guidelines and standards, drawing on pre-existing protocols for the use of RUTF for treatment of SAM and MUAC as an admission and discharge criteria within CMAM programming, and development of operational guidelines for infant and young child feeding in emergencies (IYCF-E). The national CMAM guideline and respective training manuals were reviewed and translated through the NNC with an emergency lens and approved by the relevant government authority.

The existence of relevant national nutrition in emergencies guidelines endorsed by government prior to the onset of an emergency was instrumental to the response. Guidelines require timely update in light of the latest global guidance and emerging evidence. The Nutrition Sector helped secure continued use of RUTF and RUSF for treatment of wasting in the makeshift settlements, which was critical in enabling effective malnutrition programing. A systematic Advocacy Strategic Framework for identified areas of concern affecting the response was instrumental in streamlining collective advocacy efforts and providing an enabling environment for the nutrition response. It was important that this included agreed channels for identification and communication of advocacy concerns, identification of key advocacy actors, a collectively developed advocacy implementation strategy, and means of monitoring gains and milestones achieved.

Multi-sector coordination

Pre-existing strategic ambitions for the integration of multi-sector services were largely not realised in the Rohingya response. Standalone nutrition services were developed for the emergency response under the Nutrition Sector and health services were delivered through primary health facilities under the Health Sector. This approach was fuelled by acute and high demand for services, which limited time to negotiate different ways of working together; hence, the treatment of acute malnutrition was not integrated within health structures or systems from the design phase.

Agreed national guidelines existed in Bangladesh on the use of multi-purpose cash grants during emergency response; however, this approach was restricted among the FDMN for reasons beyond the control of the Nutrition Sector. This was a missed opportunity, given the likely benefit of social protection schemes in helping to protect the nutrition status of affected households, while cash-based interventions would have facilitated uptake of recommended IYCF practices.

Since there was no agreed monitoring and evaluation framework for the integration strategy in the HRP at the onset of the response, or dedicated capacity to support this, there was no mechanism to hold to account its failure to deliver in this regard.

Conclusions

The existence of robust disaster management regulatory and policy frameworks for disaster risk reduction at country-level was instrumental in informing and coordinating governments efforts to respond to the crisis. However, the experience of the CXB FDMN response demonstrates that coordination models for complex situations such as this must be re-examined and appropriate global guidance/coordination mechanisms developed to cater for atypical and sometimes unpredictable coordination needs.

Cognisant of the central role of government in humanitarian crises, Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) among the key UN agencies working in nutrition, in line with each agency’s global mandate, should be developed and formalised at regional and country levels, based on a comprehensive analysis of current and likely future scenarios and should be fully adopted in times of crisis. This would ensure better coordination for large-scale humanitarian crises that exceed government capacity to effectively respond. MoUs should take into full account existing national and sub-national/district coordination mechanisms, capacity and challenges and should be shared, discussed and agreed with relevant government authorities at all of the right levels.

Strengthening collective preparedness measures for anticipated nutrition emergencies at country-level is instrumental in ensuring a timely, coordinated and quality nutrition response. Preparedness/contingency plans to be activated during emergencies should be developed and endorsed by each relevant authority. These plans should detail nutrition response coordination and information management roles and responsibilities, vulnerability criteria for nutrition, the minimum comprehensive package of nutrition services and should outline linkages between curative and preventive services to be adopted from the onset of a crisis. Technical, operational and managerial capacity-building initiatives for nutrition in emergency interventions should be institutionalised at multiple levels as part of the MPAs prior to onset of emergencies. A comprehensive mapping of the anticipated required nutrition supplies, human resources and technical guidance needed to implement a quality nutrition response should be undertaken, strengthened and pre-positioned in strategic locations during the pre-crisis period.

The operationalisation of inter-sector collaboration requires dedicated resource and capacity and accountability mechanisms. Timely collaboration and engagement with relevant government authorities at multiple levels from the onset of the emergency are needed to enable joint response planning and implementation, which is key to a fast, appropriate and aligned response.

1 World Risk Index 2016 http://www.irdrinternational.org/2016/03/01/word-risk-index/

2 Bangladesh Demographic Health Survey 2017

3 https://prezi.com/xylddpghsp0w/bangladesh-disaster-management-regulatory-framework/

4 https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/bangladesh/nutrition

5 Prior to the large influx, IOM Bangladesh was coordinating humanitarian assistance to some 200,000 UMNs living in makeshift settlements and host communities in Cox’s Bazar. https://www.iom.int/news/new-arrivals-bangladesh-myanmar-reach-313000-iom-seeks-usd-261-million-address-lifesaving-needs

6 Inter Sector Coordination Group (ISCG) Report, November 2018. Estimates are based on official data from the ISCG and UNHCR in Bangladesh.

7 SAG is a decision-making body for the Nutrition Sector, comprised of Civil Surgeon (CS) Office, key UN agencies and national and international NGO representatives, elected by Nutrition Sector partners.

8 https://www.unocha.org/sites/unocha/files/JRP%20for%20Rohingya%20Humanitarian%20Crisis%202018.PDF

9 Several studies/pilots on CMAM programming had generated evidence for use of RUTF/RUSF prior to the influx but there had been no policy change. CXB-specific evidence was instrumental in influencing the acceptance of continued use of RUTF and use of RUSF for FDMNs.

10 HoSO is a decision-making body for the FDMN response comprised of heads of UN agencies and NGO representatives.

11 Challenges specific to continuity of care for acute malnutrition treatment will feature in an upcoming online article. https://www.ennonline.net/fex