One UN for nutrition in Afghanistan - Translating global policy into action: A policy shift to tackle wasting

Click here to listen to an interview with Dr. Jamil Bawary, Integrated Management of Acute Malnutrition (IMAM) Officer, Ministry of Health Afghanistan

By Maureen L. Gallagher, Martin Ahimbisibwe, Dr. Muhebullah Latifi, Dr. Zakia Maroof, Dr. Said Shamsul Islam Shams and Mursal Manati

Maureen L. Gallagher is Chief of Child Health and Nutrition for United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in Mozambique. She was previously the Chief of Nutrition for UNICEF Afghanistan between 2018 and 2020. She is a public health specialist with over 20 years’ experience in health and nutrition programming in several countries in Africa and Asia.

Martin Ahimbisibwe is head of Nutrition at World Food Programme (WFP) Afghanistan. He is a Public Health Nutritionist with over 15 years of experience working in humanitarian and development contexts in over seven countries in Africa and Asia with a focus on field operations, food systems, assessments, nutrition policy and governance.

Dr. Muhebullah Latifi is Food Security Policy Officer for the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Afghanistan. He has worked in food security and nutrition programming for over 15 years at national, sub-national and field levels with the Government, non-governmental organisations and United Nations agencies.

Dr. Zakia Maroof is a Nutrition Specialist for UNICEF Afghanistan. She has worked in health and nutrition in humanitarian and development contexts for around 20 years. Prior to UNICEF, she worked with International Medical Corps (IMC) and Action Contra la Faim (ACF).

Dr. Said Shamsul Islam Shams is a medical doctor and a public health and management expert. Dr. Shams coordinates the Technical Secretariat of the Afghanistan Food Security and Nutrition Agenda now located at the Administrative Office of the President of the Government of Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.

Mursal Manati is Director of the Public Nutrition Directorate at the Ministry of Public Health Afghanistan. She is a pharmacist with a Masters’ degree in Food, Nutrition and Dietetics and has eight years’ experience in public health and nutrition, including as Director of Specialist Directorate of Afghanistan Atomic Energy High Commission (AAEHC).

Location: Afghanistan

What we know: Prevalence of child wasting remains high in Afghanistan; treatment services are underfunded, struggle to reach targets and are challenging to sustain.

What this article adds: Severe wasting treatment services in Afghanistan are delivered as part of the Basic Package for Health Services (BPHS) through government health facilities. While progress has been made to improve treatment coverage and programme performance, further scale-up has been impeded by reliance on short-term emergency funding and a narrow funding base, the insecure and expensive supply of imported ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) and a high wasting burden. Prevention is central to the vision for wasting management in Afghanistan; opportunities exist to leverage existing programmes and to play to agency strengths. To realise this, the UN agencies in Afghanistan are committed to working together as per the ‘One UN for Afghanistan’ strategy. Led by the government under the Afghanistan Food Security and Nutrition Agenda (AFSeN-A) and consistent with the UN Global Action Plan (GAP) on Child Wasting framework for action, development of an operational roadmap for Afghanistan is now underway supported by United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Food Programme (WFP), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO). By the end of 2020 it will provide detailed plans and a monitoring framework to guide a multi-sectoral package of interventions to harness the strengths and complementarity of each individual agency for greater impact. An analysis of convergence between the agencies and gaps is currently underway to inform this process. A longer-term funding strategy is integral to the outworking of this approach.

Context

Undernutrition is highly prevalent among children under five years of age in Afghanistan and is an underlying cause of the country’s high under-five mortality rate (55 per 1000 live births). Almost four out of every 10 children under five years of age in Afghanistan (37%) are stunted and one in ten children (9.5%) are wasted. Recent SMART surveys (2020) show that approximately two million children under five years in Afghanistan (1,020,000 girls and 980,000 boys) require treatment for wasting, 780,000 of whom (397,800 girls and 382,200 boys) are severely wasted. Current Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) targets are to treat 600,000 wasted children; an estimated 30,000 cases are currently reached. Afghanistan also faces persistently high levels of micronutrient deficiencies including iron, iodine, zinc, vitamin A and vitamin D. Anaemia, mainly due to iron deficiency, affects 45% of children aged 6-59 months of age, 31% of adolescent girls and 40% of women of reproductive age. Adolescent girls who are stunted, thin or anaemic are more likely to experience poor pregnancy outcomes and give birth to babies who themselves are wasted and stunted.

A large proportion of Afghanistan’s population is classified as vulnerable due to years of conflict and natural disaster-driven humanitarian crises, population displacement and disruption of essential services (Figures 1 and 2). The result is a population that is highly vulnerable to socio-economic hardship, seasonal surges in wasting, disease outbreaks (diarrhoea, acute respiratory infection and measles), poor hygiene and sanitation and poor access to food and health and nutrition services (especially in hard to reach areas). Sub-optimal feeding and care practices are also common,1 influenced by gendered social and cultural beliefs and norms, food insecurity and poor household environments.

Despite growing demands for care, the health delivery system in Afghanistan is under-resourced and reliant on external aid to maintain service delivery. While significant attention has been given to addressing wasting as a humanitarian response, wasting treatment programme coverage remains low. Programmes to address the widespread problem of child stunting also remain low in priority and scale. These issues are further aggravated by erratic climate conditions, widespread food insecurity and the hard-to-reach nature of many communities. Most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to rises in food prices, the closure of borders with neighbouring countries, reduction in mobility, loss of jobs and disruption of routine health services, leading to a fall in in-patient admissions of 50% in spite of prevalent COVID-19 in the population.2

This article examines current strategies to address the problem of wasting in Afghanistan and presents a vision for a future united effort to increase treatment coverage and address its underlying causes.

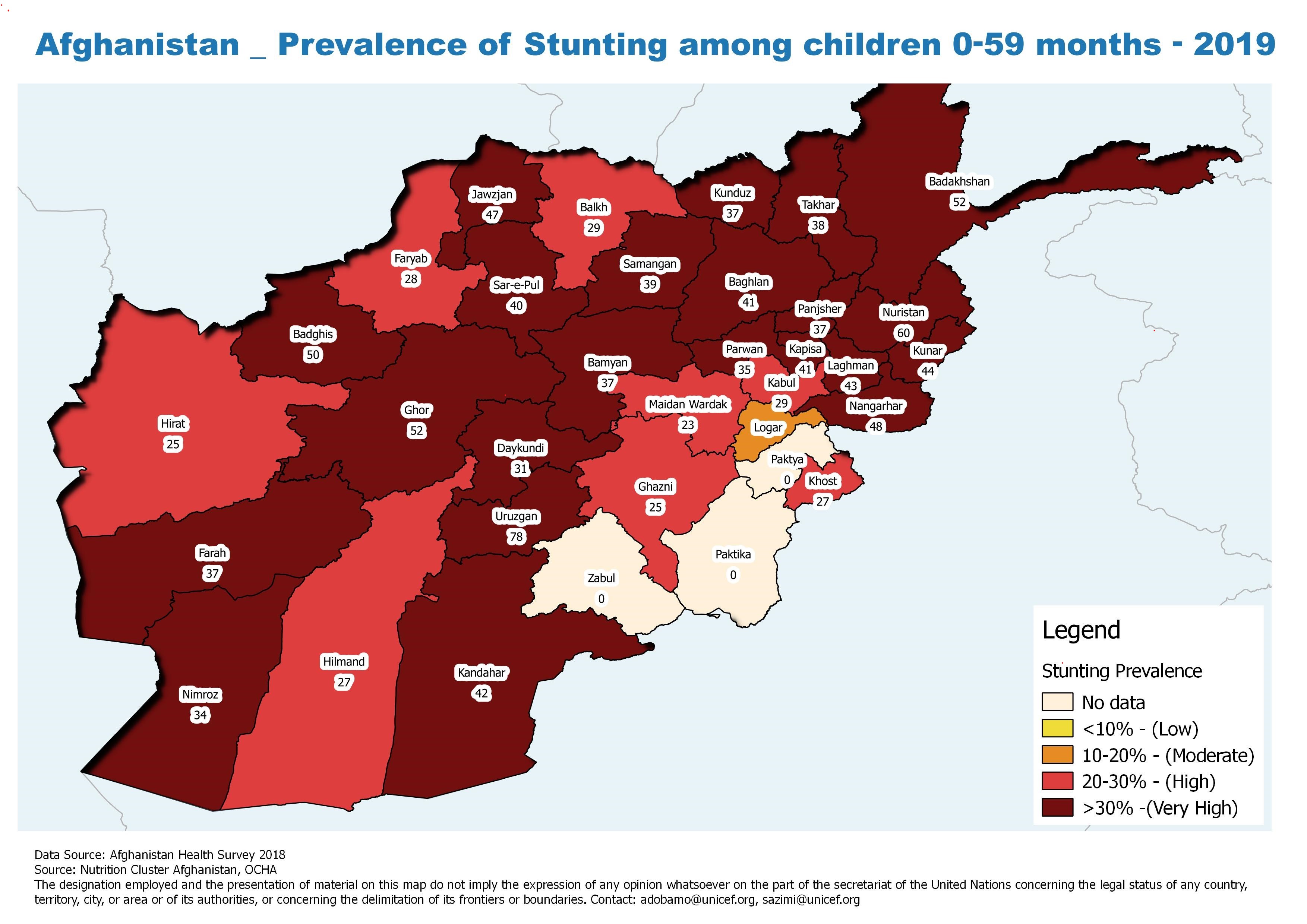

Figure 1: Prevalence of global acute malnutrition and vulnerability factors, June 2020

Classification based on wasting prevalence of 10% with one or more aggravating factors such as high incidence of diarrhoea, COVID-19, food insecurity (IPC phase 3 and above), conflict induced displacement and low immunization coverage.

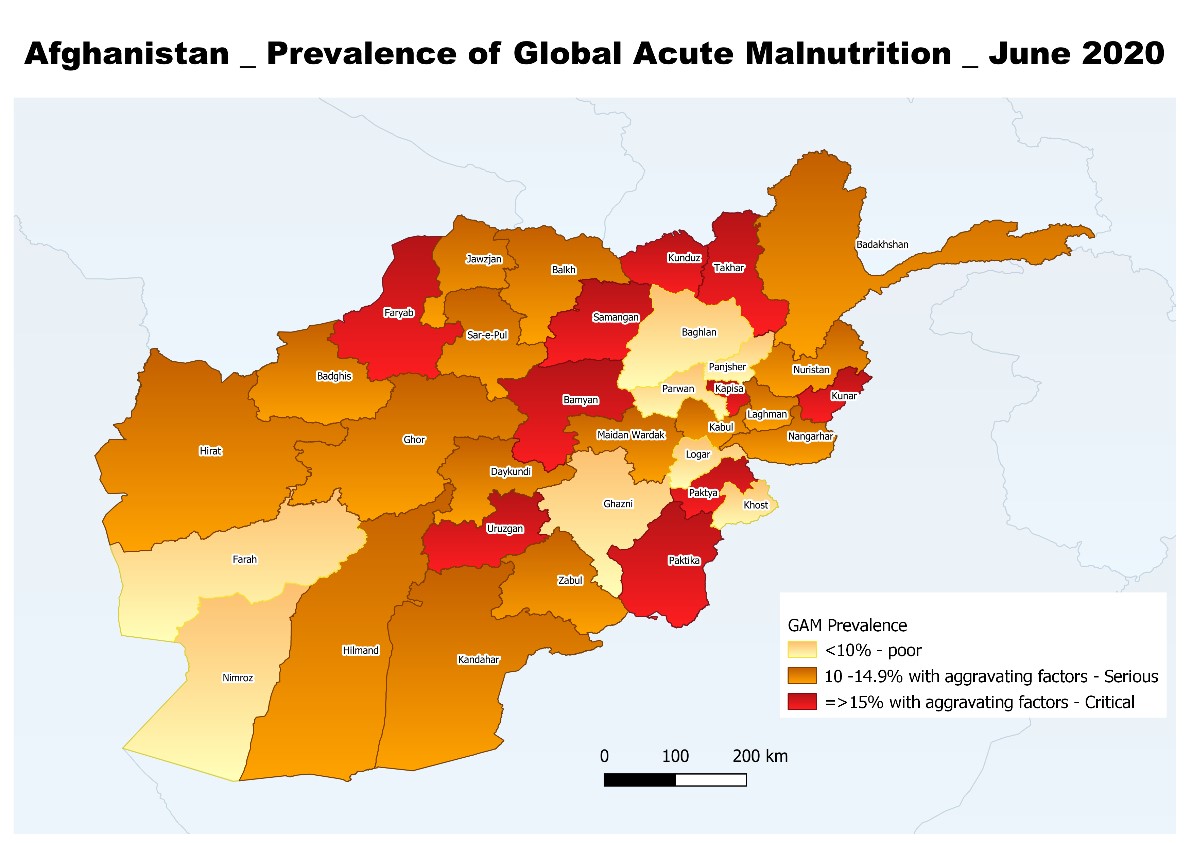

Figure 2: Mapping of provinces by stunting prevalence among children age 0 to 59 months, 2019

Current interventions and intersectoral linkages

Integrated nutrition service delivery

There has been commitment in recent years by the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) and development partners to integrate nutritional services into government systems at national and sub-national levels. Nutrition-specific services in Afghanistan are delivered predominantly through non-governmental organisations (NGOs) contracted to deliver the Basic Package for Health Services (BPHS) and the Essential Package for Health Services (EPHS) through government health facilities. These include growth monitoring, counselling on maternal, infant and young child nutrition (MIYCN) by midwives and nutrition counsellors, The Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), food fortification (salt, oil and wheat flour), weekly iron folic acid supplementation (WIFS) for adolescent girls (targeted to girls both in and out of school) and the integrated management of acute malnutrition (IMAM). Operational costs for these services, including NGO and health facility staffing, medicines and some supply transport costs, are covered by SEHATMANDI3. Costs of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) for the management of wasting are not covered and must be sourced externally.

Admission and performance data are collected monthly from health facilities and collated in a national database managed by the Public Nutrition Directorate (PND) of the MoPH. Plans to make this information available on an online dashboard are currently being finalised. Screening data is collected by the Health Management Information System (HMIS) to allow the monitoring of nutrition trends.

Scale up of wasting treatment services

Scale up of treatment services has differed for moderate and severe wasting. For severe wasting, significant scale up took place between 2016 and 2018, resulting in the doubling of coverage of health facilities to almost 60% at a cost of around USD20 million per year. In 2019, plans for further scale up were interrupted by a foreseen shortfall of RUTF supplies for the year as well as an overall funding shortfall of around 30%. Moderate wasting programming is guided by the Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP), with locations prioritised by the Nutrition Cluster based on global acute malnutrition (GAM) rates and food security vulnerability (Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) phase 3 and above). As such, moderate wasting treatment is implemented in only around 45% of health facilities, at a cost of USD28 million per year, with less than 50% programme coverage.

Further geographical scale-up of severe and moderate wasting treatment is limited by resource availability - the scaling up of severe wasting treatment services alone to around 75% coverage will require an additional USD5 million per year (to a total of USD25 million). Increased geographical coverage is also challenged by the hard to reach nature of many locations due to difficult terrain, weather and security. In some areas, this has been overcome through the use of mobile health and nutrition teams4 operated by the Directorate of Provincial Health (DoPH) through BPHS and/or non-BPHS partners (often international NGOs). There is potential for expansion of this service delivery modality, particularly in the context of COVID-19, to minimise population movement. However, funding to scale up this activity remains limited.

As the cost of supplies is not covered under SEHATMANDI, RUTF for the treatment of severe and moderate wasting is dependent on off-budget and emergency short term funding. Procurement is led by the World Food Programme (WFP) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) with funding from various donors, such as Food for Peace/United States Assistance of International Development (USAID) and pooled funding through the Afghanistan Humanitarian Fund (AHF). WFP and UNICEF also provide technical support and ad hoc training to support wasting treatment and the World Health Organization (WHO) provides support for in-patient care, including the training of health staff on the management of severe acute malnutrition, the supply of therapeutic milk preparation kits, medical equipment and medicine and the rehabilitation of water and sanitation systems of in-patient units in hospitals.

Strengths and challenges of nutrition-specific programming in Afghanistan

Much has been achieved in the strengthening and coordination of national nutrition-specific programming. Led by the government, multiple agencies including UNICEF, WFP and WHO consistently collaborate to bring a quality continuum of care closer to women and children (Box 1). Key collaborative initiatives have successfully increased admissions and the performance of wasting treatment programmes, including the training of health workers, last mile delivery of supply, counselling on MIYCN, community-based nutrition package (CBNP)5, strengthening the engagement of community volunteers and Mothers’/Family mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC).6 Other joint initiatives have been the development of MIYCN guidelines and a Social Behaviour Change and Communication Strategy and Operation Plan for Nutrition, implementation of emergency infant and young child feeding (IYCF) activities and the strengthening of community-based nutrition and food-based programmes to contribute to the prevention of stunting. The agencies have also worked together on school-based support for weekly iron folic acid supplementation (WIFS) for adolescent girls and deworming for school children and, more recently in the COVID-19 context, the expansion of the iron folic acid initiative to reach ‘out of school’ adolescents through a community-based platform (currently in pilot phase with expansion dependent on funding).

Box 1: One UN for Nutrition: A catalyst for working together for women and children in Afghanistan

The ‘One UN for Afghanistan’ strategy was designed by all UN agencies under Sustainable Development Goal 2 Zero Hunger and is synergised with national policies and programmes.

The roles and responsibilities of key UN agencies working in nutrition in Afghanistan are understood in a continuum of care framework. UNICEF, WFP and WHO are more directly involved in the treatment of wasting while FAO and other agencies work on prevention by leading nutrition-sensitive initiatives.

UN agencies support the MoPH and Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Livestock (MAIL) in technical coordination, development of strategies, guidelines/standard operating procedures, resource mobilisation, facilitation of technical working groups, capacity strengthening and programme delivery.

As part of One UN in Afghanistan, nutrition is integrated under thematic group area three linked to the Zero Hunger challenge, with nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions coordinated by a small sub-group. Agencies are all also active members of other coordination platforms - both technical and multi-sectoral - including IMAM, MIYCN, Micronutrient, Assessment Information Management (AIM), Nutrition Program Coordination Committee, Nutrition Cluster, Food Security and Agriculture Cluster (FSAC) and Afghanistan Food Security and Nutrition Agenda (AFSeN-A).

UN agencies work together on resource mobilisation - for example Afghanistan Humanitarian Fund allocations are discussed with all agencies and partners via the Nutrition Cluster. Development funding has also been secured, for example, to support a nutrition surveillance system implemented by UNICEF and WHO with the support of the Government of Canada. Longer term funding has proven to be more challenging to secure; a strong framework and advocacy approach is needed to leverage more resources.

For the COVID-19 response, all global guidance was tailored to Afghanistan and revised/validated by the Nutrition Cluster Steering Advisory Group (SAG), the Food Security and Agriculture Cluster (FSAC) as well as government-led technical working groups.

A joint implementation framework to address wasting is under discussion to harness the strengths and complementarity of individual agencies for greater synergy and more effective implementation for lasting outcomes.

Treatment scale up is hindered by problems with the ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) supply chain. As discussed, supplies for wasting management are almost entirely based on off-budget funding. Integrating treatment supplies into the essential medicine supplies (EMS) list would allow the government to purchase RUTF and help to strengthen government procurement and supply chain capabilities. Advocacy is ongoing to this end, however, this has been challenging given that RUTF is not currently integrated into the WHO global essential medicines list (EML). International procurement of RUTF is challenging - all supplies must pass through customs clearance in Karachi in Pakistan before being moved to Kabul for distribution (given that Afghanistan is landlocked) and this causes delays and breaks in the supply chain. Simplified protocols7 for the treatment of severe wasting are currently being implemented as a means of mitigating recurrent RUTF shortages in the country with treatment outcomes closely monitored to observe trends. There is interest by the government to explore other cost-efficient alternatives to replace imported RUTF and improve programme sustainability, such as local commercial production and home-based product formulations.

Another important challenge is the lack of funding to sustain and scale up nutrition services. Most donor support currently either funds coordination activities (support for the Nutrition Cluster, for which there is no focal donor) or the procurement of treatment supplies for humanitarian actions. Unlike other sectors, there is no committed longer term investment in nutrition services. Health service delivery costs around USD180 million per year as part of SEHATMANDI. National spending accounts from 2018 reported that over 75% of expenditure is out of pocket, with households having to utilise their own resources to cover health service access. In this context, it is difficult to propose an additional USD48 million (at a minimum) to cover supply costs for full coverage of wasting treatment services. Other types of longer-term bilateral funding are urgently needed to support the government to sustain programming at full scale.

A further challenge is the overwhelming and increasing burden of wasting in Afghanistan, driven by issues beyond the immediate causes of inadequate diet and disease, including household food insecurity (leading to children not receiving the right amount of the right foods at the right time), inadequate care and feeding practices, inadequate hygiene and sanitation and a lack of access to health services. These underlying causes must be tackled together in order to curb the increasing wasting burden. Prevention efforts are ongoing, for example through investment in the agriculture and health service sectors. However, investment is low compared to the contribution of the agriculture sector to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and existing agriculture and livelihoods programmes lack coverage and often do not apply a nutritional lens. Limited funding to address adolescent nutrition issues including high anaemia prevalence is also a major challenge.

Putting prevention at the heart of wasting management – a vision for Afghanistan

Opportunities to enhance wasting treatment and prevention efforts

Prevention of wasting must be central to wasting management in Afghanistan. This requires the targeting of high burden and vulnerable communities with an integrated multi-sectoral package of nutrition, health, food security, social protection and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) interventions. Tackling the underlying causes of undernutrition and strengthening nutrition resilience must go hand in hand with accessible child wasting treatment services including the under six months age group.8 Agricultural production, processing, storage, preservation and dietary diversification programmes are the main interventions being implemented as part of preventive approaches to improve access to nutritious diets, as well as social behaviour change programming. There is increasing coverage and promotion of food fortification and new evidence emerging on the availability of and access to local nutritious foods to inform future programming. The synergy between wasting prevention and treatment programmes must be improved to maximise their impact; there are currently limited referrals or shared planning between wasting treatment and livelihoods initiatives. Preliminary results from the ‘Fill the Nutrient Gap’ assessment conducted during the first quarter of 2020 show that one third of Afghans would not be able to purchase diets that meet just energy needs and four out of five households would not be able to purchase diets that meet all nutrient needs for health, development and growth. In response to drought and the COVID-19 pandemic, donors have become increasingly interested in social protection initiatives in which advocacy is succeeding in having a nutritional lens included. There are also opportunities to pilot and build the evidence on the impact of smaller scale social protection schemes.

New way of working for UN agencies in Afghanistan

The policy and programming environment in Afghanistan shows promise for an integrated prevention and treatment approach to tackle child wasting. An opportunity to bring all necessary services together lies with the government-led Afghanistan Food Security and Nutrition Agenda (AFSeN-A) - a multi-sectoral agenda and approach (analogous with the Scaling up Nutrition (SUN) Movement) with the key objective of tackling stunting and improving the overall food security and nutrition of the population of Afghanistan. The AFSeN-A Strategic Plan 2019-2023 brings together key interventions and obligations under different government ministries, some of which are funded by on and off budgets9, and led by a technical secretariat (recently transferred from the Chief Executive’s Office to the Administrative Office of the President (AOP)).

UN agencies in Afghanistan have an opportunity to bring together an integrated package of services to be delivered in high burden locations, within their complementarities and under the leadership of the government linked to the AFSeN-A Strategic Plan. The commitment to work together is already expressed within the One UN platform, however under this agreement there is no joint framework for action which limits its impact. The recently developed Global Action Plan (GAP) on Child Wasting: framework for action is a global framework for action to accelerate progress in preventing and managing child wasting and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).10 The AFSeN-A and agencies have also worked together on a complementary feeding framework with the same key areas of intervention as the GAP on Child Wasting: framework for action (health systems, food systems, WASH and social protection). These, and the development of an operational roadmap for Afghanistan, provide an opportunity to consolidate all efforts to date and bring the UN agencies together more concretely in Afghanistan to achieve enhanced outcomes. Based on the AFSeN-A Strategic Plan, the roadmap will identify agreed provinces for convergence and indicators to measure joint progress. The AFSeN-A technical secretariat will lead this process on behalf of the government to ensure that the result is in line with government priorities. Governance structures are in place to enable this through the AFSeN-A multi-sectoral coordination platforms at national and provincial levels. A common project document and monitoring plan to prevent and manage wasting nationally and in the selected priority provinces will be produced by the end of 2020.

To inform this process, the following steps are being led by the Government of Afghanistan with support from UN agencies:

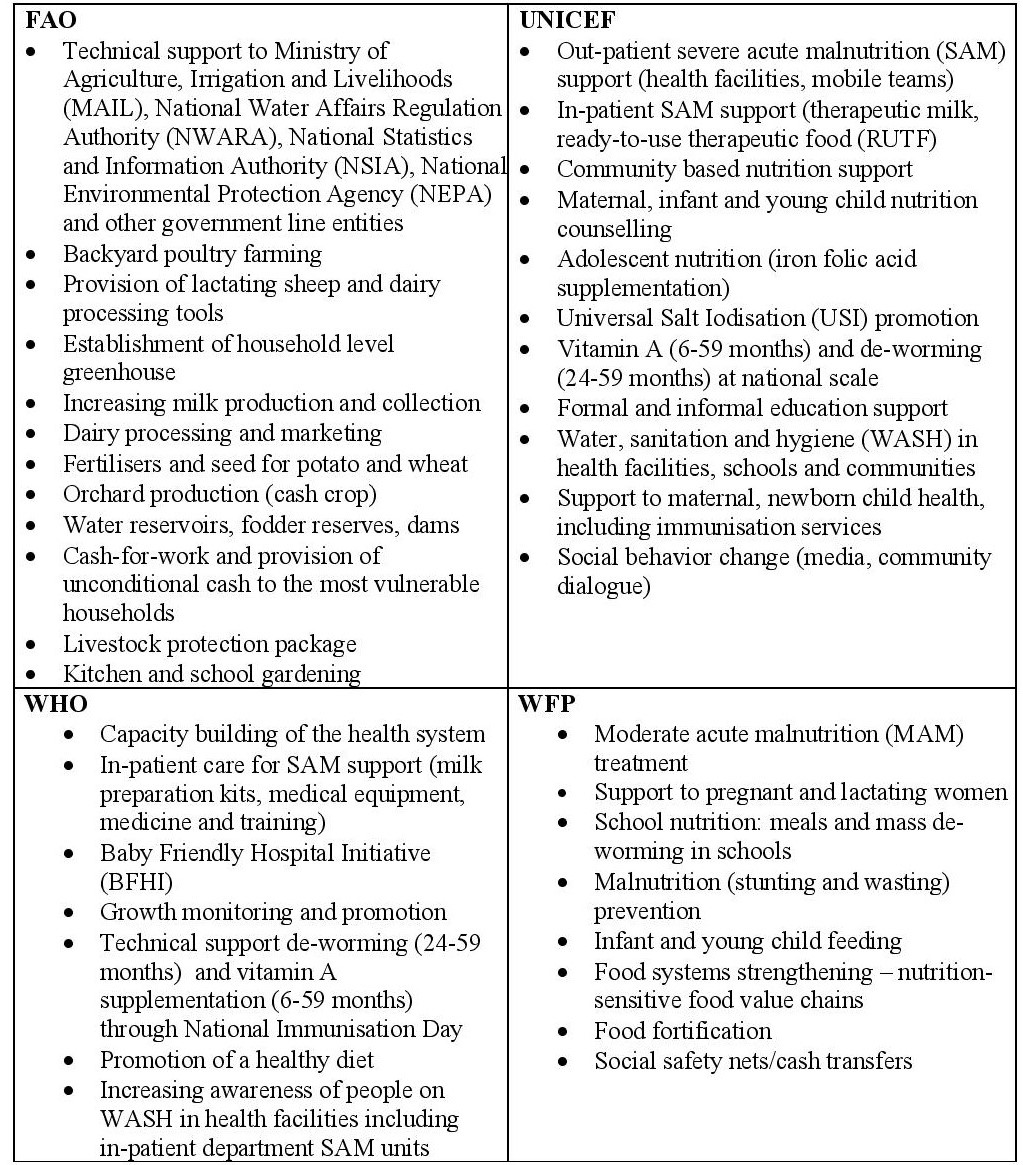

- Mapping of current interventions of UN and non-UN agencies per province, guided by the AFSeN-A Strategic Plan. Box 2 illustrates current interventions implemented by UN agencies that are in line with the National Public Nutrition Strategy, Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Livestock (MAIL) Food Security Nutrition (FSN) Policies/Strategies and the AFSeN-A Strategic Plan.

- Identification of key intervention areas to be prioritised, coordinated by AFSeN-A and MoPH/PND supported by UNICEF as Cluster Lead Agency (via Nutrition Cluster) and identified lead to coordinate the GAP on Child Wasting.

- Identification of funding gaps of mapped interventions to inform advocacy for government or bilateral funding and/or through other donors. A costing exercise will inform joint resource mobilisation between government and donors.

- Identification of areas to expand the fiscal space for funding of the action plan with government and donors.

- Reflecting the objectives of the SUN Movement in Afghanistan, advocacy for one focal donor for nutrition to coordinate and advocate for funding for nutrition with other donors.

- Stunting and wasting data will be collected on a five-year basis (Demographic Health Survey) using a comparable methodology (SMART).

Box 2: UN agency priority and common nutrition and food security programming areas in Afghanistan

Conclusion

Reducing wasting to acceptable levels in Afghanistan is within reach. However, stronger commitments from the government and donors are key to complement ongoing efforts and make this possible. The global action plan (GAP) on child wasting offers an important opportunity to consolidate the work done and build on it. UN agencies in Afghanistan are strongly committed to work together, driven by the government under Afghanistan Food Security and Nutrition Agenda (AFSeN-A) and coordinating with key ministries, to develop and operationalise a roadmap for Afghanistan. The transitioning of AFSeN-A to the Administrative Office of the President (AOP) and the UN agencies’ continuous collaborative intentions to jointly address the nutritional situation in Afghanistan makes the last quarter of 2020 a prime time for planning and advocacy. In the past, there has been over reliance on humanitarian funding for treatment services and no focal or champion donor to lead donor advocacy efforts. A broader funding strategy is urgently needed to support the effort to develop longer term solutions towards the sustained prevention and treatment of child wasting in Afghanistan.

For more information please contact Dr. Zakia Maroof.

1 While 63% of Afghan mothers initiate breastfeeding early within one hour, the rate of exclusive breastfeeding of children aged 0-5 months remain low at 58%. Inadequate diets, lack of food diversity and poor micronutrient quality are major concerns; only 16% of children aged 6-23 months receive the minimum acceptable diet.

2 Results of a national survey to estimate COVID-19 morbidity and mortality in Afghanistan conducted in July 2020 show that people in Kabul and east region provinces were most affected by COVID-19 with 53% and 42.9% of people respectively testing positive (IgM and IgG testing).

3 SEHATMANDI is the System Enhancement for Health Action in Transition Project for Afghanistan with the objective to expand the scope, quality and coverage of health services provided to the population, particularly to the poor, in the project areas, and to enhance the stewardship functions of the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH).

4 Ahmad Nawid Qarizada, Maureen L. Gallagher, Abdul Qadir Baqakhil and Michele Goergen (2019). Integrating nutrition services into mobile health teams: Bringing comprehensive services to an underserved population in Afghanistan. Field Exchange 61, November 2019. p 62. www.ennonline.net/fex/61/mobilehealthteams

5 CBNP is a community participatory approach to strengthen community based nutritional services within the 1,000 days and includes community growth monitoring, mapping of foods seasonally, food demonstrations amongst other activities to empower communities to address their nutritional situation.

6 Whereby mothers are trained to screen their own children for wasting using MUAC tapes.

7 In October 2019 and in order to mitigate the impact of an anticipated shortage of RUTF nationally, the MOPH agreed to start implementing a simplified protocol in five provinces, involving the reduction of RUTF dosage for the treatment of SAM children.

8 Partners are currently reviewing existing protocols and identifying options for implementation of community-based management of infant wasting

9 On budget is financing by donors that is often channeled through government. Off budget is additional donor funding for projects and programmes and channeled through partners. There are efforts in Afghanistan to have these increasingly linked and aligned to prevent duplication and maximise use.

10 https://www.childwasting.org/the-gap-framework and the views article in this edition entitled, “UN Global Action Plan (GAP) framework for child wasting and the Asia and Pacficic Region”