Integration of essential nutrition interventions into primary healthcare in Pakistan to prevent and treat wasting: A story of change

Click here to listen to an interview with one of the authors on the ENN podcast channel

By Dr Baseer Khan Achakzai, Eric Alain Ategbo, James Wachihi Kingori, Saba Shuja, Wisal M Khan and Yasir Ihtesham

Dr Baseer Khan Achakzai is Nutrition Director for the Ministry of National Health, Service, Regulation and Coordination, Pakistan. He is a public health professional with over 26 years of experience working with the Government of Pakistan, managing multiple national public health programmes in the Federal Health Ministry.

Eric Alain Ategbo is Chief of Nutrition for the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Pakistan. He is a nutritionist with over 30 years of experience, previously working for UNICEF in Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Niger, Uganda and India, and in the Department of Nutrition and Food Science, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, University of Benin.

James Wachihi Kingori is a Regional Nutrition Officer for the World Food Programme (WFP) Asia and Pacific. He is a nutritionist with over 20 years of field experience with non-governmental organisations and United Nations agencies in Africa, Middle East, Asia and the Pacific.

Saba Shuja is a Nutrition Officer for UNICEF Pakistan. She is a public health professional with more than 15 years’ experience in health and nutrition.

Wisal M Khan is a Nutrition Specialist for UNICEF Pakistan. He is a public health professional with more than 20 years’ experience in health and nutrition.

Yasir Ihtesham is acting Head of Nutrition for WFP Pakistan. He is a public health practitioner with more than 12 years’ experience in nutrition in emergencies and development contexts with United Nations agencies.

Location: Pakistan

What we know: Child wasting levels remain extremely high in Pakistan and coverage of wasting treatment services is low.

What this article adds: Community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) was first implemented in Pakistan in 2005 as an externally funded, standalone intervention in response to the Azad Kashmir earthquake, and later in response to subsequent crises in Punjab and Sindh provinces. In 2010 the Government of Pakistan (GoP) developed national CMAM guidelines (updated in 2015), used to guide CMAM programming in priority districts, co-funded by GoP and external partners from 2011 onwards. The programme was delivered through a government health service delivery platform, but was vertical with its own workforce, supply chain and information management system. In October 2018 external partners capitalised on the GoP’s signing of the Astana Declaration on Universal Health Coverage and advocated for inclusion of a package of essential nutrition-sensitive actions (including CMAM) in the public health system. This approach has been accepted by the GoP and the essential nutrition package is being costed to inform resource allocation for stepwise rollout. Plans are being made to develop the capacity of the health work force (including lady health workers - Pakistan’s cadre of community health workers) to deliver services and integrate CMAM supplies and data into the routine supply chain and information systems.

Background

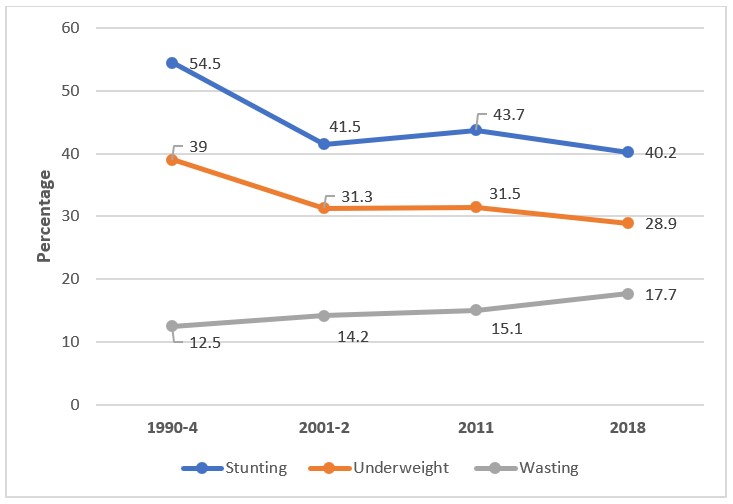

Pakistan is the sixth most populous country in the world (Statistics PBo, 2018), with an estimated 39% of the population affected by poverty (GoP, 2018). Child undernutrition remains a persistent public health problem, contributing to high child mortality rates (currently 74 deaths per 1,000 live births) and hampering socioeconomic development. A cost-of-hunger study carried out by the Government of Pakistan (GoP) and World Food Programme (WFP) in 2017 revealed that Pakistan is losing USD7.6 billion annually as a result of the costs of malnutrition, corresponding to 3% of gross domestic product (GDP). The rates of wasting (acute malnutrition) and stunting (chronic malnutrition) in children under five years old remain very high in Pakistan, at 17.7% and 40.2% respectively (GoP and UNICEF, NNS 2018). While a very slow but downward trend is observed for prevalence of stunting among young children, prevalence of wasting has shown a steady upward trend over the last three decades, increasing from 12.5% in 1990 to current levels of 17.7% (Figure 1). The prevalence of severe wasting or severe acute malnutrition (SAM) has also increased, from 5.8% in 2011 to 8.0% in 2018 (GoP and UNICEF, NNS 2011, 2018).

Child undernutrition in Pakistan has multiple complex causes. An important driver at individual level is maternal undernutrition, which is a major cause of high levels of low birth weight (LBW) in the country (around 20%). Maternal undernutrition is reflected in prevalent anaemia, (42.7%), vitamin A deficiency (22.4%), vitamin D deficiency (54%), wasting (14.4%), and overweight and obesity (38%) among women of reproductive age (GoP and UNICEF, 2018), as well as low uptake of iron and folic acid (IFA) supplementation among pregnant women (32.9%). Early marriage and low maternal education are also associated with child undernutrition (Khan et al, 2019). Sub-optimal infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices are also highly prevalent, with only half of infants under six months exclusively breastfed and less than one in 20 (3.5%) infants over six months receiving complementary foods that meet the requirements of a minimum acceptable diet. Other underlying causes of undernutrition in Pakistan include food insecurity (58% of households are estimated to be food-insecure (GoP MPDR, 2018), inadequate care, inadequate access to and utilisation of social basic services, and widespread poverty.

To increase the coverage of child wasting treatment and thereby contribute to the reduction of child morbidity and mortality, the GoP adopted and began implementing Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) from 2005. CMAM was initially implemented as a standalone emergency nutrition intervention, later evolving into a government-owned intervention that is now being integrated into primary healthcare for countrywide roll-out. This article describes the evolution of this process, key enablers, barriers and lessons learned.

Evolution of the approach to wasting treatment in Pakistan

CMAM as a donor-funded, stand-alone emergency response

Over the last 15 years Pakistan has endured several major, unprecedented disasters; some natural (earthquakes, floods and droughts) and others man-made (widespread militancy and resulting operations), with devastating impacts on food and health systems. In 2005 an earthquake in Pakistan-administered Azad Kashmir and adjacent Khyber Pakhtunkhwa led to floods in Jhal Magsi Balochistan and internal displacement into Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. To tackle resulting high levels of wasting, Pakistan implemented its first CMAM programme. Core elements of the programme included community screening, inpatient care for complicated cases of SAM, and outpatient management of uncomplicated SAM and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) through use of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) and ready-to-use supplementary food (RUSF) respectively. The primary aim of this decentralisation of treatment was to rapidly increase the coverage of wasting treatment services beyond levels achieved through facility-based programming alone. This was a vertical, standalone, life-saving emergency response that was mainly dependent on external donor funding and humanitarian agencies.

Between 2005 and 2011 CMAM programming was implemented in response to multiple emergency situations in Pakistan; all as donor-funded, vertical, life-saving responses. This included the response to the monsoon flash floods and riverine in 2010 and 2011 in Punjab and Sindh provinces, devastating one third of the country and resulting in widespread displacement, disruption of social services, livelihoods and agriculture, and inflicting vast infrastructural damage. The Nutrition Cluster was rapidly established at provincial and district levels to coordinate the nutrition response in affected areas and CMAM was implemented by externally funded non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and United Nations (UN) agencies, partially delivered through available government health service delivery structures.

The success of the nutrition emergency response in averting a significant number of deaths brought the spotlight on the CMAM approach in Pakistan. To avoid the suspension of nutrition services post-emergency and continue building on the gains made during the crisis, the Government of Pakistan (GoP), with support from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), World Food Programme (WFP), World Health Organization (WHO) and NGOs, developed Pakistan-specific CMAM guidelines in 2010 (updated in 2015). The purpose of the guidelines was to provide a framework to guide the management of acute malnutrition. However, implementation of the guidelines was mainly limited to emergency response, and wasting treatment (as with other nutrition interventions) was not integrated into the routine package of health services.

CMAM as a government-funded vertical programme

In 2012, the GoP initiated CMAM in selected emergency and non-emergency districts based on results of the 2011 National Nutrition Survey (NNS), district population size and availability of funds from the government and external donors (mainly World Bank). In the provincial nutrition projects (PC1) developed for 2016-2019, CMAM covered all 36 districts in Punjab, nine districts in Sindh, seven districts in Balochistan and several districts in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Punjab has since extended its CMAM programme to the entire province, alongside a stunting prevention programme in selected districts of south Punjab. Similarly, Sindh has continued CMAM programming through an accelerated action plan (AAP) covering 12 districts, 10 of which include CMAM programming supported with funds from the European Union Programme for Improved Nutrition in Sindh (PINS). CMAM programming has also continued and has been extended in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and is in the process of extension (through renewal of the PC1) in Balochistan. In this model the identification of children with wasting is the entry point for all nutrition services, including infant and young child feeding (IYCF) promotion, micronutrient powder supplementation and SAM treatment.

In this system, CMAM continued to be implemented as a vertical programme, located ‘under the same roof’ as health services within each province, but with separate staff (management staff and a separate cadre of nutrition assistants), supply chain and information management system not integrated within existing government systems. Challenges to this way of working included a fragmented information system, weak supply and logistics management, and reliance on short-term funding grants, resulting in a lack of sustainability. Programme coverage therefore remained limited; in 2019 around 265,000 children were treated countrywide for SAM and 157,000 children were treated for MAM, with an overall coverage of around 5%.

Opportunity to mainstream nutrition-specific interventions into Pakistan’s routine package of primary healthcare services

In October 2018 the GoP fully endorsed the Astana Declaration on public healthcare revitalisation1 and initiated actions to revisit the primary healthcare approach to drive universal health coverage. This provided a unique opportunity to leverage health service delivery platforms to deliver nutrition services. Nutrition partners, including the World Bank, UNICEF, WHO, and WFP, seized this opportunity to advocate to the government for the mainstreaming of wasting treatment and prevention services through the inclusion of selected nutrition-specific interventions into the routine package of services delivered at primary healthcare level. As a result, it was agreed that a ‘minimum essential nutrition package’ (which included wasting treatment services and key prevention and promotion services, including IYCF counselling, vitamin A supplementation, deworming and multiple micronutrient supplementation (MMS) for children and pregnant and lactating women) would become part of the Universal Health Benefits Package, delivered routinely through the government health system by the existing health workforce. Along with this, it was decided that nutrition supplies would be integrated into the health commodities logistics management system, nutrition indicators would be incorporated in the Health Management Information System (HMIS), and oversight of nutrition services would be enhanced, to enable programme sustainability.

Box 1: Primary healthcare system in Pakistan

The primary healthcare model in Pakistan was first envisaged in the sixth five-year plan of the Government of Pakistan (GoP) (1983-1988). Since that time there has been considerable investment in the primary healthcare system. Now, a strong infrastructure for primary healthcare exists, managed through provincial governments, with a network of community health workers, community midwives, basic health units (BHUs) and rural health centres (RHCs). There are currently over 14,351 government health institutions in Pakistan, including 1,279 hospitals; 5,671 dispensaries; 686 RHCs, 5,527 BHUs, 747 maternal child health centres and 441 TB clinics.2

Lady health workers (LHWs) are a cadre of frontline health workers who provide services in their communities, supervised and supported by lady health supervisors, who provide services at health facilities. Hired and placed locally, the primary responsibilities of LHWs are to provide basic promotive, preventive and curative services in their communities, including family planning and maternal and child health services. LHWs receive training, support, medical supplies and pay from their closest public health facilities.

Under the 18th amendment to the constitution, the GoP has devolved many ministries to the provinces, including health and population welfare. This provides the provinces with opportunities for strategic planning as well as resource allocation and management at provincial level. Despite having a strong primary healthcare network, until now nutrition programmes have not been incorporated into the system but have worked vertically as standalone programmes, with their own workforces, supply chains and information management systems, in spite of being delivered in the same health facilities.

Process of integration

The process of integrating the minimum essential nutrition package into the primary healthcare system in Pakistan is being guided by the Disease Control Priority approach (DCP3) (Box 2), with support from a Technical Group led by the Government of Pakistan (GoP) Ministry of Health with input from United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Pakistan is the first country to adopt the DCP3 and is being supported to do so with technical assistance from Liverpool University in the UK.

Box 2: Disease Control Priority Approach (DCP3)

Disease Control Priorities 3 provides a periodic review of the most up-to-date evidence on cost-effective interventions to address the burden of disease in low-resource settings. DCP3 defines a model concept of essential universal health coverage with 218 interventions that provide a starting point for country-specific analysis of priorities. Assuming steady-state implementation by 2030, essential universal health coverage in lower-middle-income countries would reduce premature deaths by an estimated 4·2 million per year.

Costing and resource allocation

A cost-effectiveness analysis for the proposed package, including the minimum essential nutrition package and key health and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) interventions, was carried out by the Ministry of National Health Services, Regulation and Coordination (MoNHSR&C). To support the process, the Nutrition Section of the MoNHSR&C, with technical support from UNICEF, is facilitating the development of a nutrition investment case for each of the four provinces of Pakistan. Optima Nutrition3 is being used to guide investment in nutrition for higher impact. This will inform advocacy for the allocation of the necessary resources to implement the management of wasting at scale in Pakistan through the primary healthcare system.

Development of workforce capacities

Currently, nutrition services are largely delivered by nutrition assistants at health-facility level. They are a special cadre of staff who are not on government payroll and are recruited as project staff when resources allow and laid off when financial support ends. This arrangement is far from sustainable. There is an opportunity to utilise Pakistan’s army of community lady health workers (LHWs) more proactively to provide nutrition services to rapidly increase coverage in a far more sustainable way. This approach of delivering nutrition services through LHWs has been evolving in Pakistan over the last seven years and has now been integrated into the federal PC-1, currently being finalised, which is set to boost the coverage of nutrition services through LHWs from 60% to 80%.

To enable this approach in-service training will be required for LHWs, as well as other cadres of facility-level health staff, including health service managers. The first round of training is targeted at district-level managers; the second round is with nutrition assistants. The district-based nutrition assistant (facility-based) will then engage LHWs for a simplified version of training. A huge challenge will be the provision of quality training for such a large number of individuals. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, rather than using a face-to-face approach, GoP and UNICEF are currently exploring options for online nutrition training. Similar plans are also being considered for pre-service health training. The quality of such training curricula has been a challenge in the past and will be an important area of focus going forward. Sufficient graduate and postgraduate human resources will also be required for the coordination and management of nutrition-service implementation. This will require advocacy for the inclusion of nutrition in the curricula of medical schools and tertiary institutions.

Integration into government supply chain and information systems

Local production of lipid-based specialised nutrient supplements (ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) and ready-to-use supplementary food (RUSF)) for the treatment of MAM and SAM are now at advanced stages of production and are being used in the implementation of CMAM programming. To sustain local production, the GoP has passed a bill for tax exemption on imported raw materials used in RUSF production; efforts are being made to obtain similar exemption for RUTF production. This will increase the cost-effectiveness of the programme and pipeline sustainability, and will enable the expansion of production. Efforts are also underway to include imported multiple micronutrient supplementation (MMS) tablets and sachets in the essential drugs list. In addition, key prioritised nutrition indicators are currently being integrated within the existing District Health Information System (DHIS), which will fully streamline nutrition information and reporting within the government health information system.

Institutional arrangements

In recent years there has been greater political commitment to tackle widespread undernutrition in Pakistan, leading to the development of the Pakistan Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy (PMNS) 2018-2025. The PMNS aims to link and coordinate sector nutrition strategies in all four provinces of the country and optimise federal support for nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive programming. The Ministry of National Health Services, Regulation and Coordination is the lead ministry responsible for the delivery of nutrition-sensitive interventions in this strategy. Wasting treatment and prevention strategies are implemented through the health sector (supported by the Nutrition Section in the Planning and Development Division of the Ministry of Health). The PMNS target, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals, is to reduce and maintain childhood wasting to <5% in Pakistan by 2025, or at least to achieve a reduction in child wasting of 0.5% per year between 2018 and 2025. In emergencies, management and resource allocation is the responsibility of the National Disaster Management Authority, which must work closely with the primary healthcare network for the delivery of surge support. Ongoing efforts to mainstream nutrition into primary healthcare through the universal health coverage approach, if successfully completed, will offer the opportunity to bring these efforts to scale to reach wasting reduction targets.

Current programme coverage remains low, with less than 10% of children with SAM having access to treatment. A huge effort is required to increase coverage through a stepwise approach, starting with a focus on the areas of the country at high risk of polio; after which the focus will expand to districts with high burdens of SAM, followed by expansion to the whole country. Opportunities to integrate these efforts with ongoing social protection schemes and wasting prevention programmes in Pakistan are being explored and leveraged.

Conclusions

Work has been ongoing for several years to transition nutrition programming in Pakistan from emergency-driven, vertical programming to a systematic, developmental approach to address malnutrition through the primary healthcare system. Continuous advocacy and sensitisation of policymakers have driven change towards the full, nationwide integration of nutrition services into the primary healthcare system. While accepted at policy level, these changes are yet to be rolled out in practice. The immediate next step is to add wasting management to the health function of the Government’s Five-Year Plan (2018-23) and National Action Plan (2019-23) and to advocate for the allocation of adequate financial resources, based on the nutrition investment case, to implement the minimum essential package of nutrition services. This government-led approach is key to enabling full coverage of wasting prevention and treatment services to meet national wasting reduction targets.

For more information, please contact Eric Alain Ategbo.

Figure 1: Childhood malnutrition trends in Pakistan

© Source: 1990-4 NHS; 2001-2 NNS; 2011-NNS; 2018-NNS

References

Government of Pakistan Finance Division (2018) Pakistan Economic Survey 2018-2019. Available from: www.finance.gov.pk/survey/chapters_19/Economic_Survey_2018_19.pdf

Government of Pakistan and UNICEF (2018). Pakistan National Nutrition Survey 2018. Available from: www.unicef.org/pakistan/reports/national-nutrition-survey-2018-key-findings-report

Government of Pakistan Ministry of Planning, Development and Reform (GoP MPDR) (2018) Pakistan multi-sectoral nutrition strategy 2018-2025.

Khan, S., Zaheer, S. & Safdar, N.F. Determinants of stunting, underweight and wasting among children <â5âyears of age: evidence from 2012-2013 Pakistan demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health 19, 358 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6688-2

Statistics PBo. Monthly Bulletin of Statistics, 2018 [updated June 2018]. Available from: www.pbs.gov.pk/sites/default/files/other/monthly_bulletin/monthly_bulletin_of_statistics_july16.pdf.

1 In 2019 countries around the world agreed to the Declaration of Astana, vowing to strengthen their primary healthcare systems as an essential step towards achieving universal health coverage. www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health/declaration/gcphc-declaration.pdf

2 www.pbs.gov.pk/content/health-institutions-beds-and-personnel

3 Optima Nutrition is a quantitative tool that can provide practical advice to governments to assist with the allocation of current or projected budgets across nutrition programmes. http://optimamodel.com/