Integration of family planning in nutrition programming: experiences from the Suaahara II programme in Nepal

By Basant Thapa, Manisha Laxmi Shrestha, Dr. Bhuwan Poudel, Ganga Khadka, Bijendra Banjade and Dr. Kenda Cunningham

Basant Thapa is a family planning advisor for the Suaahara II programme and has over 27 years of experience in public health, HIV, nutrition, reproductive health and family planning and health system strengthening with different international organisations.

Manisha Laxmi Shrestha is a nutrition specialist for the Suaahara II programme and has over eight years of experience in national nutrition programming.

Dr. Bhuwan Poudel is senior public health administrator for the Bagmati Province Government in Health Office, Dhading, Nepal and has nearly two decades of experience in the provision of government health services.

Ganga Khadka is a nutrition and health officer for the Suaahara II programme based in Dhading and has over three years of field experience in the implementation of nutrition and health programmes.

Bijendra Banjade is a nutrition and health officer for the Suaahara II programme based in Kapilvastu and has over six years of field experience in nutrition, health system strengthening, Water, hygiene and sanitation (WASH) and gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) with different organisations.

Dr. Kenda Cunningham is the senior technical advisor for integrated nutrition and monitoring, evaluation and research for learning in the Suaahara II programme.

All authors deeply acknowledge the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) (Grant/Award number: 367-A-11-00004) for its financial support. The contents of this manuscript are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Location: Nepal

What we know: Family planning is an important nutrition-sensitive intervention that is often overlooked in nutrition and food security programming.

What this article adds: This article provides an example of how to integrate family planning and nutrition programming by highlighting experiences and lessons learned from the Suaahara II programme in Nepal. The Suaahara II programme aims to reduce widespread undernutrition, particularly among mothers and children within the first 1,000 days of life, through interventions spanning nutrition, health and family planning, Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), agriculture and markets and nutrition governance. Family planning messages were integrated throughout household and community level social and behaviour change activities to improve knowledge and increase demand for high-quality family planning services. Cautious interpretation of the project monitoring data from surveys conducted among a randomly selected sample of households in 2017 and 2019 suggests some modest but positive trends in family planning indicators. Leveraging existing platforms across sectors helped deliver integrated messages to beneficiaries and ensured that messages were reinforced in diverse platforms. Programme experience and monitoring data show that utilising multiple communications channels and reaching multiple household members increased the possibility of desired behaviour changes.

Overview of nutrition and family planning in Nepal

Nepal is a small landlocked country with tremendous geographic, ecological and cultural diversity. Half of Nepal’s population of 26 million live in the low-lying southern plains known as the terais, the other almost half (43%) live in the middle hills and around 7% live in the northern mountains (Government of Nepal, 2014). Forty percent of Nepal’s population is under the age of 18 years (Government of Nepal, 2018).

Nepal remains burdened by public health challenges including malnutrition as evidenced in the latest Demographic and Health Survey (Government of Nepal, 2016). Among adolescent women 15 to 19 years of age, 17% are already mothers or pregnant with their first child and around 17% of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) are thin (body mass index <18.5). This is of concern not only for the women themselves but also for their offspring, given that thin mothers are more likely to give birth to low birth weight (LBW) infants at high risk of being undernourished themselves thus perpetuating the intergenerational cycle of malnutrition. The national prevalence of infants born with LBW is 12%. The prevalence of stunting (short height-for-age) among children under five years of age decreased from 57% in 1996 to 36% in 2016 whereas wasting (low weight-for-height) among children aged 6 to 59 months has remained high at around 10%. Poor infant and young child feeding contribute to child undernutrition: only 66% of infants under six months of age are exclusively breastfed and only 35% of children 6 to 23 months of age receive a minimum acceptable diet.

The rate of unintended pregnancies has declined significantly in the previous two decades in Nepal from 37% in 1996 to 19% in 2016 and the unmet need for family planning (FP) 1 declined from 31% to 24% over the same two decades (Government of Nepal, 2016). This positive trend was driven by the long-term collective efforts of the Government of Nepal (GoN) and external development partners who have targeted marginalised and excluded populations with interventions including intensive social and behaviour change approaches to mitigate the social taboos and negative norms around family planning.

Nepal is committed to improving the health status of its people including reducing undernutrition. Nepal’s National Health Policy (2019) describes a vision where all Nepali citizens have access to services, enabling high levels of physical, mental, social and emotional health. This is outworked through a tiered healthcare delivery system structured at federal, provincial and municipality/community levels. Nepal’s Multisector Nutrition Plan 2018 – 2022 (MSNP II) guides improved maternal, adolescent and child nutrition in the country through the scale up of essential nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions (Government of Nepal, 2017). The MSNP II prioritises the reduction of existing disparities in levels of stunting and wasting (by wealth quintile, level of maternal education, geographical area and household food insecurity), promotion of equity, improvement of poor performing interventions, the scale up of low coverage interventions and addressing emerging challenges (Haag et al., 2020). The MSNP II also states the importance of increasing access and coverage of FP and reproductive health services as a key element of improving the quality of life for families and communities. This is to be achieved by enabling women and couples to attain their desired family size and have healthy spacing of childbirths by improving access to rights-based FP services and reducing the unmet need for modern contraceptives (Government of Nepal, 2015).

Box 1: The links between family planning and nutrition

The period from conception to 24 months of age – often called the first 1,000 days of life – is a critical time to prevent undernutrition. When children are well-spaced (at least 24 months spacing after a live birth), mothers are more likely to have the time, energy and resources to recuperate the essential nutrients required resulting in better nutrition outcomes in children. The benefits of optimal birth spacing have far-reaching effects into childhood and are associated with reduced prevalence of stunting in children under five years of age (Naik and Smith, 2015).

Early pregnancies and childbearing can have negative health, nutrition and development consequences for adolescent mothers and their babies. Complications related to pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of death among adolescent girls aged 15-19 years globally (Neal et al., 2012). Additionally, babies born to mothers aged under 20 years face higher risks of low birth weight, preterm delivery and severe neonatal conditions (WHO, 2016). Evidence suggests that children from unintended pregnancies may be at risk of poor nutrition, underscoring important linkages between family planning and nutrition (Naik and Smith, 2015).

FP and nutrition are intricately linked and affect the nutritional wellbeing of individuals in direct and indirect ways (see Box 1). Family planning is therefore an important nutrition-sensitive intervention. However, FP is often overlooked in nutrition and food security programming – nutrition programmes do not generally include messages about the when, what and how of modern contraceptive methods or the healthy timing and spacing of pregnancy (HTSP). Conversely, FP providers do not usually provide information about maternal and infant nutrition. Integration of FP into nutrition programming, including harmonising counselling and services with maternal, infant and young child nutrition (MIYCN) from pre-pregnancy to early childhood, provides an opportunity to improve coverage of services towards universal health coverage (as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development) and improve health and nutrition outcomes for both mothers and children. This article provides an example of how this kind of integration can be achieved in practice in the context of the Suaahara II programme, highlighting experiences and lessons learned.

Suaahara II programme: overview and integration of family planning into nutrition

The Suaahara II programme (SII) is an integrated nutrition programme funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) covering all communities of 42 of Nepal’s 77 districts. SII is a continuation of a previous programme, Suaahara, which was a five-year USAID-funded programme implemented from 2011 to 2016. SII started in April 2016 as a five-year USD63 million programme that was recently extended until March 2023 with additional funding of USD20 million. The international non-governmental organisation (NGO), Helen Keller International (HKI), is the lead partner for the programme which is implemented through a consortium with six other organisations: two international NGOs (CARE and FHI 360) and four national NGOs (Equal Access, Environment and Public Health Organization (ENPHO), Vijaya Development Resource Center (VDRC) and Nepali Technical Assistance Group (NTAG)). Another 39 partner NGOs (PNGOs) implement activities at the district level, mainly within communities and households, across the 42 programme districts.

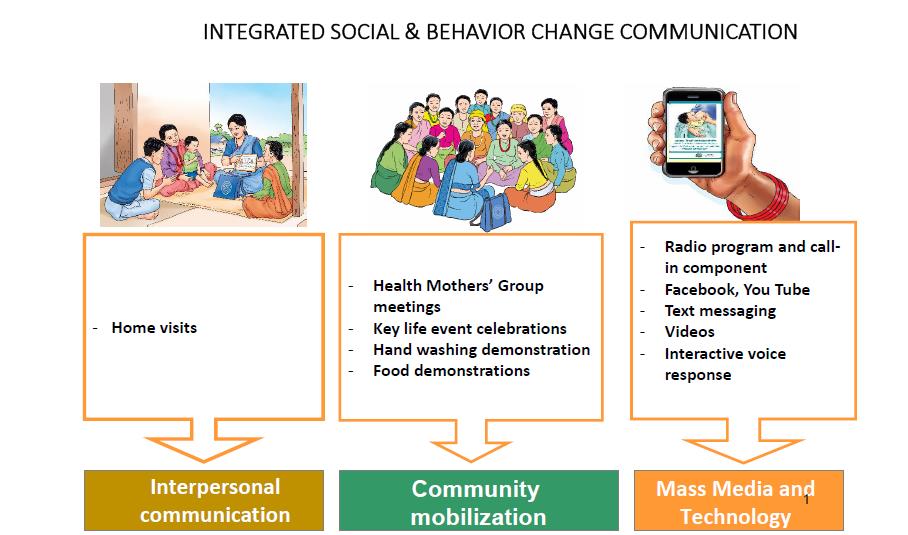

SII aims to reduce widespread undernutrition in Nepal, particularly among mothers and children within the first 1,000 days of life, with interventions spanning nutrition, health and FP, Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), agriculture and markets and nutrition governance. Using a gender equality and social inclusion approach for all interventions, SII’s multi-sectoral social and behaviour change strategies are integrated across all of these sectors to reach thousands of communities and include inter-personal communication (IPC) (primarily home visits by SII-hired frontline workers), community events (e.g., key life events celebrating the start of pregnancy, delivery and an infant reaching six months of age), mass media (primarily a weekly radio programme also available on Facebook and YouTube) and text messages (see Figure 1). As of September 2020, nearly two million households with children in the first 1,000 day period were reached, targeting not only mothers but other family members including men and mothers-in-law.

FP, focusing on three key HTSP messages, is integrated throughout these SII household and community-level activities to improve knowledge and increase demand for high-quality FP services. For example, around 10% of the episodes of SII’s flagship weekly Banchhin Aama radio programme and live call-in component are purely dedicated to FP/HTSP, a text message focused on HTSP is sent to postnatal mothers, ideal FP is promoted through social media platforms and FP-related messages are integrated within the materials and job aids of SII’s nearly 1,500 frontline workers (such as an FP edutainment game to discuss misconceptions related to the side effects of modern contraceptive use) and social and behaviour change communication (SBCC) materials used by Female Community Health Volunteers (FCHVs) during home visits and in community platforms.

Gender inequality is pervasive in Nepal affecting household decision-making including the ability of a woman to control whether she uses FP services. Extending FP messages to the 1,000 day household members through SII’s family-centred approach is important for overcoming these barriers as they go beyond a mother’s knowledge.

Figure 1: Integrated SBCC approach of the Suaahara programme

At the health service delivery level, integration of FP and HTSP into nutrition services began with revisions to the GoN’s MIYCN training package. This training is given to all health workers and FCHVs to enhance their nutrition-related knowledge. This package will now also include training sessions to improve their ability to provide FP/HTSP counselling and services. Furthermore, job aids that include integrated messaging on both nutrition and FP/HTSP are also provided. As of September 2020, these have been provided to all 2,111 health facilities in the 42 SII implementation districts. SII encourages health workers to counsel on the lactational amenorrhea method (LAM) of FP which also helps to extend breastfeeding. SII also conducts routine monitoring of 50 to 60 health facilities per month for on-site coaching to address remaining knowledge and skill gaps and assess service readiness and status of key commodities, equipment and essential supplies including follow-up for timely reporting.

Partnerships and linkages

SII works in partnership with the GoN to revise and develop various nutrition-related guidelines, protocols and training manuals and SBCC materials to integrate FP and HTSP. SII actively participates in government-led Technical Working Group meetings, provides technical support and advocates for the scale-up of SII’s integration approach. Similarly, SII community-based staff continuously advocate and collaborate with local government bodies to encourage resource allocation and utilisation to address supply-side barriers such as gaps in commodities, equipment and other essential supplies. Additionally, SII builds linkages and collaborates with other development programmes to increase demand for integrated services and promote and replicate best practices. For example, SII shares its project monitoring data related to supply-side stock- outs of essential commodities of FP on a quarterly basis with other health system programmes as part of strengthening the government planning and monitoring system. To ensure that key behaviours related to MIYCN/FP/HTSP are sustained, constant efforts are made at federal, provincial and local levels so that the key behaviours being promoted by the project continue beyond its intervention.

SII has also integrated FP/HTSP information beyond the health sector. For instance, SII has integrated key FP/HTSP messages in the training of Village Model Farmers and also leads discussions on these topics during Homestead Food Production Beneficiaries group meetings. To expand beyond SII, collaboration with the USAID-funded Knowledge-based Integrated Sustainable Agriculture project in Nepal included integration of these key FP/HTSP messages into their training package which helped reach male farmers groups across their 24 programme districts. Additionally, FP and HTSP messages are also incorporated in an integrated job aid, known as the Health Mothers’ Group calendar, used by FCHVs to facilitate systematic agenda-based discussions during monthly meetings.

Early indications of improvement

The findings from SII’s annual monitoring surveys conducted in 2017 and 2019 among a randomly selected sample of households with a child 0-5 years of age suggest some modest but positive trends in FP indicators although the results should be interpreted with caution in the absence of control groups and a more rigorous evaluation (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Progress in family planning indicators in Suaahara II programme areas, 2017 and 2019

|

Indicators |

2017 |

2019 |

|

Prevalence of women getting married at 20 years and older |

25% |

28% |

|

Prevalence of women avoiding pregnancy (FP practices among non-pregnant mothers) |

40% |

44% |

|

Prevalence of married women using any modern method of FP |

36% |

38% |

|

FP/HTSP knowledge among household heads (A women should wait to become pregnant until she is 20 years or older) |

52% |

53% |

|

FP/HTSP knowledge among mothers (A women should wait to become pregnant until she is 20 years or older) |

58% |

59% |

Source: Suaahara II programme data (Annual Monitoring Survey Report, 2019)

Implementation challenges

Challenges are inevitable in a multi-sectoral programme with large geographic coverage such as SII that covers more than half of Nepal. Successful integration has required continuous advocacy with government stakeholders at national and sub-national levels to allocate resources for activities in line with the ideals of integrated services as they would naturally have their own, but differing, priorities. Another challenge has been the limited time of health workers and FCHVs who have activities under multiple interventions. This has, at times, led to FP being overlooked, particularly for FP counselling sessions when more urgent health and nutrition needs have been prioritised. Quality assurance is also difficult for integrated services and large-scale programmes. In consideration of this, SII provides systematic on-site coaching and mentoring to healthcare providers to ensure delivery of high-quality integrated services at health facilities and to continue to build knowledge and skills. Finally, it can be challenging to reach disadvantaged populations with all the components of integrated services as barriers to adopting behaviours from multiple sectors vary from one population group to another. For example, those people struggling most to achieve dietary diversity may differ from those needing additional support to adopt modern FP practices or WASH practices such as treating drinking water and hand washing with soap as barriers to each of these practices naturally differ. This suggests the need for different targeting strategies by sector. To mitigate this issue, SII focuses its interventions and sharpens its targeting and behaviour changes approaches regularly.

Learnings and potentially replicable interventions

The need for the integration of FP and nutrition programming is evident. Building bridges across sectors using integrated approaches implemented through different delivery platforms provides opportunities for addressing knowledge gaps and bolstering demand generation of integrated services. Scaling-up best practices of integrated services requires the continuous building of technical and management capacity and collaboration with a wide group of stakeholders at all levels. Continual capacity building of the facility- and community-based healthcare providers through on-site coaching and mentoring is vital.

The SII family-centred approach is crucial to promoting shared responsibility among family members rather than relying exclusively on mothers to adopt optimal behaviours such as delayed marriage and first pregnancy. This can support a reduction in the prevalence of maternal and child undernutrition and related child morbidity and mortality and ultimately reduce intergenerational cycles of malnutrition in resource constrained settings. Additionally, leveraging existing platforms across sectors helps to deliver integrated messages to beneficiaries and ensures that messages are consistently reinforced using diverse platforms. Our programme experience and monitoring data show that utilising multiple communications channels and reaching multiple household members increases the possibility of desired behaviour changes.

Finally, working alongside the government at all levels is vital for the long-term sustainability of these investments. In the decentralised governance context of Nepal, a gradual increase in resources allocated through local level planning would help to sustain the efforts that have been initiated for the improved delivery of integrated services and this would contribute to achieving Nepal’s commitments to providing a comprehensive package of essential health and nutrition services through universal healthcare coverage.

For more information, please contact Dr. Kenda Cunningham.

Subscribe freely to receive Field Exchange content to your mailbox or front door.

Endnotes

1 Family planning is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the ability of individuals and couples to anticipate and attain their desired number of children and the spacing and timing of their births.

References

Annual Monitoring Survey Report. (2019). Suaahara II Good Nutrition Program, Nepal. http://careevaluations.org/wp-content/uploads/Suaahara-II-Annual-Survey-Report-2.pdf

Government of Nepal. (2014). Population Monograph of Nepal. National Planning Commission Secretariat, Central Bureau of Statistics, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Government of Nepal. (2015). National Family Planning Costed Implementation Plan 2015-2020. Ministry of Health and Population, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Government of Nepal. (2016). Nepal Demographic and Health Survey. Ministry of Health and Population, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Government of Nepal. (2017). Nepal’s Multi-sector Nutrition Plan 2018-2022. National Planning Commission, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Government of Nepal. (2018). Country Program Action Plan 2018-2022. UNICEF, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Haag, K. C., Sharma, A., Parajuli, K. and Adhikari, A. (2020). Experiences of the Integrated Management of Acute Malnutrition (IMAM) programme in Nepal: from pilot to scale up. Field Exchange issue 63, www.ennonline.net/fex

Naik, R. and Smith, R. (2015). Impacts of Family Planning on Nutrition. Washington, DC: Futures Group, Health Policy Project. https://www.healthpolicyproject.com/pubs/690_FPandnutritionFinal,pdf

Neal, S., Matthews, Z., Frost, M., Fogstad, H., Camacho, A. V., and Laski, L. (2012). Childbearing in adolescents aged 12–15 years in low resource countries: a neglected issue. New estimates from demographic and household surveys in 42 countries. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 91(9), 1114-1118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01467.x

WHO. (2016). Global Health Estimates 2015: Death by Cause, Age, Sex, Country and Region, 2000-2015 World Health Organization, Geneva.