“I’m courageous”: a social entrepreneurship programme promoting a healthy diet in young Indonesian people

By Cut Novianti Rachmi, Dhian Probhoyekti Dipo, Eny Kurnia Sari, Lauren Blum, Aang Sutrisna, Gusta Pratama and Wendy Gonzalez

Cut Novianti Rachmi has vast experience conducting impact evaluations and using a mixed-method approach for various research topics. She is currently a senior researcher at Reconstra Utama Integra, Jakarta, Indonesia.

Dhiah Probhoyekti Dipo is Director of Public Health Nutrition at the Ministry of Health, Republic of Indonesia. She holds a Master’s degree in health planning and policy from the University of Leeds, UK and a doctoral degree in public health from the University of Indonesia.

Eny Kurnia Sari is a programme manager for adolescent nutrition at the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). She has over 12 years of experience managing rural and urban development programmes for local and international non-governmental organisations.

Lauren Blum is a nutritional anthropologist working for GAIN to carry out qualitative evaluations of programmes. She has extensive experience conducting qualitative research on maternal and child health and nutrition and infectious disease in Africa and Asia.

Aang Sutrisna is Head of Programme of GAIN Indonesia. In the last 15 years, he has worked as a research, programme monitoring and evaluation consultant for various international institutions.

Gusta Trisna Pratama is a medical doctor with a Master’s degree in infection and immunology. As a research associate at Reconstra Utama Integra, he is involved in various research projects.

Wendy Gonzalez is Senior Technical Specialist at GAIN. She has experience conducting implementation research on nutrition programmes in Latin America, East Africa and Southeast Asia.

We acknowledge the contribution of Zineb Félix, Yayasan Ashoka Pembaharu Bagi Masyarakat and Dentsu Indonesia in the design and implementation of Saya Pemberani. We thank Ananda Partners for their research guidance and Hafizah Jusril and Adila Saptari for their research assistance. This programme was funded by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Location: Indonesia

What this article is about: This article reflects on the opportunities and challenges of using social entrepreneurship to engage young people in promoting healthy diets.

Key messages:

- Using the social entrepreneurship approach, the Saya Pemberani programme aimed to engage young people living in urban areas to articulate solutions to contextual problems that preclude healthy diets through social media campaigns and mentorship activities.

- While social media was an effective channel to reach young individuals in the programme areas, the participants preferred in-person mentorship sessions as a means to advance their ideas and receive personalised advice.

- According to the participants, the mentorship programme helped them to gain skills on leadership, teamwork, problem solving, critical and creative thinking and communication. The participants also reported becoming more aware and knowledgeable about the importance of, and challenges to, achieving healthy diets.

Background

Healthy diets are a prerequisite to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as they protect against malnutrition in all its forms, as well as noncommunicable diseases (IFPRI, 2016). Healthy diets are required to ensure that the 62 million young people aged 15-29 years in Indonesia, representing 20% of the country’s population, have adequate nutrition to reach their full potential and become productive adults. However, survey data from 2018 showed that 25% of girls 15-24 years of age suffer from anaemia, while 34% of girls and boys 13-24 years of age are overweight or obese (National Institute of Health Research and Development Ministry of Health, 2019).

Transforming food systems so that they provide safe, nutritious and affordable food and deliver on the SDGs by 2030 requires action by all, including young people (Glover & Sumberg, 2020) who have the potential to become powerful forces for social change (USAID, 2014). With new technology accelerating the exchange of information and ideas, young people are able to engage in issues they care about and organise themselves to promote change in their societies. Despite these opportunities, young people face a range of barriers to making structural changes related to healthy diets including a lack of involvement in key policy and political decision-making processes affecting their lives (USAID, 2014). Young people are increasingly demanding greater inclusion and meaningful engagement and are taking action to address societal challenges including through social entrepreneurship. Social entrepreneurship aims to create value or generate a positive change on society by offering solutions to social challenges (United Nations, 2020).

Using the social entrepreneurship approach, the Saya Pemberani programme (“I’m courageous” in Indonesian) aimed to engage young people living in urban areas in articulating solutions to contextual problems that preclude healthy diets. Teaming up with Ashoka, a non-profit organisation that fosters social entrepreneurship, and in close collaboration with the Indonesian Ministry of Health, the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) designed and implemented the programme between April 2019 and June 2020 in the city of Surabaya and the Jember district in East Java, Indonesia. This article describes the design, implementation, key results and learnings of the Saya Pemberani programme and reflects on the opportunities and challenges of using social entrepreneurship to engage young people in promoting healthy diets.

Designing and implementing Saya Pemberani

Theory of change: Promoting healthy diets through a social entrepreneurship approach

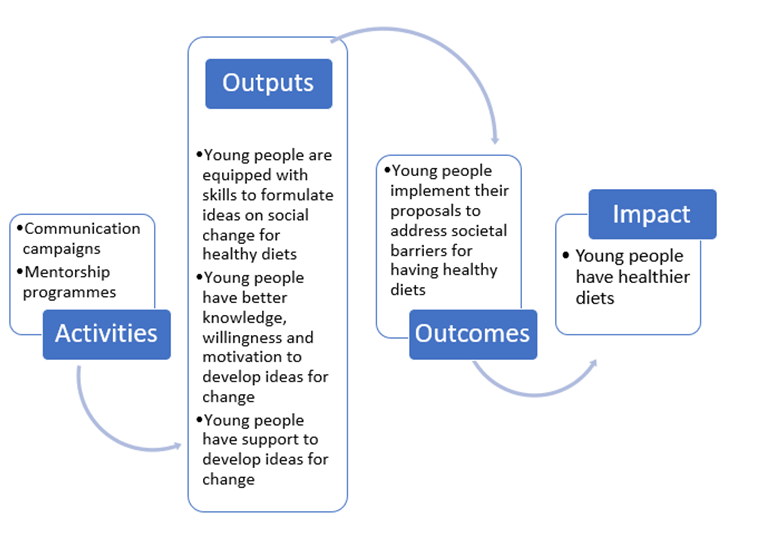

We hypothesised that if we raised awareness of and motivation for addressing barriers for healthy diets, adolescents would feel encouraged to take action and formulate ideas on social change for healthy diets. By engaging in Saya Pemberani’s mentorship programme, adolescents would strengthen the skills needed to turn these ideas into feasible, well-grounded proposals. By involving parents and teachers in this process, the programme would create a supportive interpersonal environment conducive for social change. In the long term, the implementation of these proposals would contribute to improving adolescents’ diets. (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Saya Pemberani’s theory of change

Communications campaign: Inviting youth to engage

Saya Pemberani was launched by implementing school workshops and a social media campaign. The communication campaign aimed to raise awareness about the challenges that young people in Indonesia face to eating healthy diets and to transform the role of youth in addressing the barriers to consuming nutritious foods. Through in-person events and the use of social media platforms, such as Facebook and Instagram, the programme invited young people to discuss these challenges and to generate ideas on social change for healthy diets. In addition, it organised in-person events with parents and teachers to encourage their support of young people with ideas about social change and to create a supportive interpersonal environment.

Mentorship sessions: Receiving ideas and bringing them to life

The youth mentorship sessions sought to build the necessary skills for young people to clearly articulate their ideas and bring them to life.

Young people aged 12-20 years were invited to submit ideas on social change for healthy diets to the programme’s online platform. In total, 362 collective and individual submissions were received, 78 of which were complete applications that included a brief problem description, the proposed solution and the potential for impact and sustainability. The programme recruited eight young individuals (five females and three males) from Ashoka to conduct the mentorship sessions. The mentors conducted a first session with the selected participants to help them to refine problem statements and define the steps needed to translate their ideas into actions. Those who participated in school workshops received in-person mentorship while those reached via the social media campaign received online mentorship.

Based on the participants’ engagement during the mentorship sessions and how complete the submitted idea was, the mentors selected the top 45 ideas to receive a second mentorship session. After the second session, the participants developed a one minute video presenting their refined ideas. These videos were rated by the programme’s team based on creativity, potential for impact and sustainability. The masterminds behind the top 25 ideas participated in the ‘Do it, Grow it’ summit conducted in Jakarta on 24 February 2020. During this event, the programme team mentored the participants on leadership strengthening, teamwork, collaboration and communication skills. After the ideas were presented to a select panel of judges consisting of youth innovators, communication experts and representatives from GAIN, Ashoka and government institutions with youth programmes including the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education, the top three ideas received further mentoring support to transform their ideas into well-grounded, fundable proposals (Box 1).

Saya Pemberani’s participants proposed innovative ideas for social change. Most of these ideas focused on developing nutritious food and beverage products such as tempeh (traditional Javanese food made from fermented soybeans) ice cream, healthy burgers, vegetable snacks and fruit drinks. Other ideas involved creating community gardens, designing communication campaigns or mobile apps for nutrition education, igniting a social movement around eating locally-produced foods and advocating for free access to potable water in schools.

Box 1. Description of Saya Pemberani’s top three ideas

Idea #1 – “Food Investigator initiative” to improve food safety

Dina is a junior high school student in the small village of Desa Selodakon in Jember, East Java. Realising that many school canteens and markets in her village sold expired food, she and her team developed the “Food Investigator initiative” to raise awareness amongst students and vendors about the importance of food safety, to educate vendors on practices that would ensure food safety and to inspect retail stores and school canteens to check for the presence of expired food.With support from school and local village officials, the team implemented the Food Investigator initiative in their neighbourhood. In collaboration with the school student councils, school principals and religious and local community leaders, the team plans to expand the implementation of the Food Investigator initiative to surrounding areas. They also plan to offer it as one of the extracurricular activities in schools and promote it through social media. In the long term, the team aims to influence local food and nutrition policies to strengthen the enabling environment to ensure the availability of safe foods.

Idea #2 – “Green garden” to increase the availability of fresh fruits and vegetables

Living in the diverse city of Surabaya, Andrew noticed that some children had short stature for their age and thin bodies. Linking these problems to inadequate nutrition, Andrew was motivated to improve the availability of nutritious foods to help children grow and thrive. Andrew and his team, a group of friends motivated to improve nutrition, came up with the BUJO (or Green Garden) idea which invites neighbours to plant food crops or vegetables in a public garden or designated area while implementing the concept of ‘Plant-Grow-Harvest-Use/Sell-Recycle’. BUJO’s long-term goal is to institutionalise this initiative so that people around the country benefit from the increased availability of fruits and vegetables in their communities.Idea #3 – “Sister Health”: an App to map food vendors

When Rizal was a freshman, he and his friends experienced food poisoning after visiting food vendors around their university campus. Rizal discovered that most food vendors had low sanitation standards, exacerbated by limited access to clean water and poor waste management. With his team, he developed Sister Health, an android-based application with a map of food vendors around the campus who followed hygienic practices and sold nutritious food. The app contains various features such as tips and tricks for healthy eating and a star-rating system for students to assess the hygiene of food vendors. In the long term, the team plans to build a student movement to improve food hygiene and sanitation around the university premises.

Programme assessment

Reconstra (a research focused organisation), with guidance from Ananda partners (a social entrepreneurship organisation), conducted an independent process evaluation between March and December 2020. The study aimed to assess Saya Pemberani’s reach (to what extent the programme reached its intended audience), fidelity (to what extent the programme components were implemented as intended) and the participants’ satisfaction (how the participants characterised their engagement with Saya Pemberani).

In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted remotely with a purposive sample of 58 individuals involved in Saya Pemberani. The respondents included seven representatives of the organisations who led the programme design and implementation (two respondents from GAIN, three from Ashoka and two from Dentsu), eight mentors, four jurors, four teachers, nine parents (four out of the top 25 ideas, five out of the top 10 ideas) and 26 participants.

Results

Reach

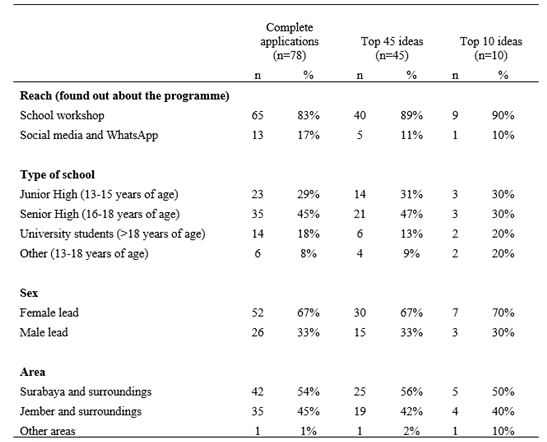

Young people from different areas, age groups and schools participated in the programme (see Table 1). Through the school workshops, Saya Pemberani reached 1,166 students and teachers from 23 private and public schools. The social media campaign generated 10,535 clicks to the programme’s website.

A total of 78 complete applications were submitted by teams of young people. The young people reached via school workshops submitted more ideas and produced more ideas that advanced to the following rounds. Students from the Santa Maria Junior and Senior High School in Surabaya submitted a high number of applications, 16 of which were shortlisted to the top 45 ideas and three of which made it to the top 10.

Table 1: Characteristics of Saya Pemberani’s ideas

Programme fidelity

Programme fidelity

The majority of Saya Pemberani’s activities were implemented as planned although a few adjustments were made to accommodate the larger than expected number of submissions. For instance, the duration of the social media campaign was shortened from 95 to 52 days and participants were encouraged to collaborate and to merge similar ideas. Eight mentors were assigned to conduct the sessions, four in Surabaya and four in Jember. As planned, they each conducted three in-person and/or online mentoring sessions.

In-person mentoring sessions were organised in convenient settings for the participants including schools, libraries and coffee shops. The sessions were held as group discussions and aimed to facilitate meaningful interactions among the teams of youth participants. The number of participants during each session was larger than expected, especially during the first session. By the third session, each mentor managed between five and seven groups. Each mentoring session lasted for approximately 90-120 minutes. As complementary activities, online webinar sessions on media and communication, leadership skills and nutrition were led by experts in these areas. In addition, the mentors and participants engaged in frequent discussions via WhatsApp groups and calls.

Participants’ satisfaction

According to the participants, the mentorship programme helped them to gain skills on leadership, teamwork, problem solving, critical and creative thinking and communication. The participants also reported becoming more aware and knowledgeable about the importance of, and challenges to, achieving healthy diets. Both the participants and mentors mentioned that engaging with Saya Pemberani improved their food choices and intake of nutritious foods.

By the end of the programme, most teams that participated in the three mentorship sessions were able to articulate well-grounded proposals for social change with a clear problem statement, rationale, theory of change and defined targets. However, both mentors and participants recommended extending the duration and intensity of the programme to further meet project goals. Teams who did not advance to the final rounds, but who were committed and motivated to bringing their ideas to life after the programme’s completion, suggested that additional follow up activities and opportunities for engagement be made available. To promote the continuity of proposed actions, Saya Pemberani linked the participants to Ashoka’s broader network of individuals with social entrepreneurship skills called the Kampung Pembaharu (village of changemakers).

Young people faced various challenges to participating in the mentorship sessions and refining their ideas including tight schedules, academic obligations and other competing priorities. Aware of these challenges, the mentors maintained flexibility in scheduling the in-person and remote discussions with the groups.

Lessons learned and recommendations

The combination of offline and online activities garnered attention and engaged a wide range of participants including very young adolescents, individuals living in peri-urban areas, with a greater number of girl participants. While social media was an effective channel to reach young individuals in the programme areas, the participants preferred in-person mentorship sessions as a means to advance their ideas and receive personalised advice. The participants valued engaging with mentors and peers during in-person activities which highlights the importance of creating social connections and promoting real-life interactions during this formative life stage.

Saya Pemberani purposively targeted those with access to technology without initially considering the digital inequity of its target population. The participants from Surabaya and wealthier families had better connectivity and access to electronic devices which helped them to engage closely with the mentors and access resources and tools to ‘fine tune’ their ideas. The programme adapted to account for these inequities, with both the mentors and judges considering the participants’ access to resources when supporting and evaluating the teams’ progress and ideas. Future initiatives should assess if there are disparities in digital access among their target population and devise strategies to mitigate their impact on diverse programme participation and engagement.

In addition to the digital inequity, the programme had to consider the age differences between the participants. Younger adolescents had trouble participating in group discussions that were generally dominated by older individuals. While programmes can segment their target population to include individuals of similar age groups, there is value in bringing people of different ages together, as they have different perspectives and can learn from each other (e.g., through mentorship sessions among age groups). Programmes can facilitate more inclusive and equitable participation by taking age-specific needs and capabilities into account and adopting recommended practices such as using jargon-free language, being mindful of the power dynamics in the groups and safeguarding the rights of younger participants to speak freely at any time (USAID, 2014).

Saya Pemberani’s participants identified and articulated context-specific problems that interfere with or limit healthy eating. Refining barriers to safe and healthy eating into problem definitions was not a straightforward task as it required the capacity to understand complex ideas and to think abstractly. The participants benefited from Saya Pemberani’s guidance on problem definition which helped them to gain a better understanding of the nutrition situation in their cultural context. They followed a step-by-step problem articulation process by conducting a detailed root-cause analysis. By framing the problem from their perspective and understanding, the participants were better equipped to craft relevant solutions specific to their local environment that resonated with their peers.

The successful pursuit of social entrepreneurship is dependent on the confluence of enabling factors and conditions. The Santa Maria Junior and Senior High School, which championed and supported Saya Pemberani, achieved a high number of applications; participants from this school mentioned teachers and parental support as key facilitators for programme engagement. The participants also reported that engaging with Ashoka’s larger network of social entrepreneurs provided essential support, motivating them to continue working on their ideas and to produce high-quality proposals.

Conclusion and future direction

Saya Pemberani helped the participants to gain and reinforce leadership and transversal skills such as complex problem solving, analytical skills and creativity which prepare them to navigate both current and future challenges. The programme helped to increase the participants’ and mentors’ knowledge and motivation for eating healthy diets. While the programme generated an influx of creative and innovative ideas, it also illuminated that young people need guidance and support to refine their proposals. A phase-out strategy involving informal guidance from mentors or peers can help to ensure that participants continue to receive support even after a programme reaches completion.

By adopting the social entrepreneurship approach, the programme sought to engage the participants as leaders (as opposed to partners or contributors) who were responsible for developing the proposals from ideation to target setting and planning for implementation. Saya Pemberani played a facilitator role by providing advice, creating links and opportunities to interact and exchange ideas and reinforcing the skills that enabled the participants to pursue their own goals. The Food Investigator proposal became the basis for a successfully funded project aimed at developing a gaming application to promote better food choices by adolescents, marking a major accomplishment of the entrepreneurship approach.

Adopting a social entrepreneurship approach can help to build relevant programmes for young people. Future initiatives should devise strategies to implement more diverse programme participation. Partnering with organisations that have well-established relationships with their communities can help to engage young people from disadvantaged groups such as low-income populations and out-of-school individuals.

For more information, please contact Wendy Gonzalez at wgonzalez@gainhealth.org

References

Glover, D and Sumberg, J (2020) Youth and Food Systems Transformation. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.00101

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) (2016) The new challenge: End all forms of malnutrition by 2030. Global Nutrition Report, IFPRI, Washington D.C. https://doi.org/10.2499/9780896295841_01

National Institute of Health Research and Development Ministry of Health (2019) Indonesia Basic Health Research (RISKEDAS). Ghdx.healthdata.org. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/indonesia-basic-health-research-2018

United Nations (2020) World Youth Report: Social Entrepreneurship and the 2030 Agenda. Un.org. https://www.un.org/development/desa/youth/world-youth-report/wyr2020.html

USAID (2014) Youth engagement in development: Effective approaches and action-oriented recommendations for the field. Usaid.gov. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00JP6S.pdf