Experiences from implementation of a school-based nutrition programme in Wakiso District, Central Uganda.

By Lorna B Muhirwe, George K Kiggundu, Michael Nsimbi and Maginot Aloysius

Lorna Muhirwe is the head of health and nutrition for Save the Children in Uganda. She is a public health professional with experience in developing country contexts at national, district and community levels of the health system.

George Kiggundu is a programme officer in the Baana project implementing both nutrition and WASH interventions in Wakiso District, Central Uganda on behalf of Save the Children International. He is a Public Health Nutritionist with field-based practical experience in food security, public health nutrition and community development programmes.

Michael Nsimbi is a health educator working with Wakiso District Local Government. Michael has worked with Save the Children on school health and nutrition interventions since 2016 and has trained school health clubs, school patrons and head teachers on school-based nutrition, WASH and integrated child health days.

Location: Uganda

What this article is about: This article outlines a school-based nutrition programme targeting adolescents that incorporated healthcare and interventions, parent-led school feeding and the creation of school gardens.

Key messages:

- By fostering strong linkages between schools and health facilities, high coverage of nutrition-specific activities was achieved for children in programme supported schools.

- The programme highlights that parent-led school feeding programmes are feasible in resource constrained contexts and that they can achieve positive results.

Maginot Aloysius works as a school health and nutrition coordinator in the Baana project. He is a Public Health Nutritionist with seven years’ experience in implementing nutrition, food security and livelihood plus health programmes in stable, emergency and recovery contexts.

The authors would like to acknowledge Save the Children US, Save the Children Korea and Save the Children Italy who are the core funders of the programme. The authors also thank the district education and health teams for their ongoing support and cooperation.

Background

Malnutrition affects over 21% of school-going children in Africa and contributes to immediate and long-term adverse consequences for development and health (Best et al, 2010). Although data on the nutrition status of school-aged children in Uganda is limited, the available evidence indicates that micronutrient deficiencies are common with anaemia rates reaching 46% in girls 11-14 years of age (Barugahara et al, 2013). The prevalence of undernutrition in children aged 5-19 years is 31% among boys and 17% among girls alongside rising burdens of overweight, 16% in girls and 5% in boys (Global Nutrition Report, 2020).

The Ugandan government recognises the importance of school feeding in the national development and learning outcomes for children and has ensured that the policy and legislative environments are supportive of its implementation at scale (National Planning Authority, 2020).

The Education Act of 2008 (ULII, 2008) puts the responsibility on parents and communities to support school feeding either in cash or in kind (i.e., food brought to school). When this system is in place, school administrators, together with parents and communities, determine an appropriate amount of either money or food to be provided per child with a preference towards cash when this is not a prohibitive option for the household.

In 2013, the Ministry of Education and Sports (MoES) issued guidelines on school feeding and nutrition interventions that provided instructions about how to increase access to parent-led school feeding and improve dietary diversity in schools. The guidelines also recommend school-based implementation of complementary interventions such as deworming and improved access to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH). Deworming and vitamin A supplementation are jointly funded by the government of Uganda and the Ministry of Health and primarily implemented via bi-annual Integrated Child Health Days in April and October of each year. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, bimonthly community outreach was also introduced to ensure that children who were vulnerable and not attending school were reached.

As such, the proposed Uganda School Health Policy 2018-2023 recommends a minimum school health package that includes health promotion and education, the prevention of diseases, safe water and sanitation provision, a healthy and safe school environment and other health/nutrition interventions. While this policy remains in draft format, Save the Children is working with the government to support its approval as well as with district-level government to support local, community-led implementation of school feeding. This article shares the experiences from the implementation of such a school-based nutrition programme in Wakiso District, Central Uganda.

Programme description

The school health and nutrition programme forms part of Save the Children’s wider ‘Baana’ sponsorship programme. The Baana programme supports communities in Wakiso District, Central Uganda through integration across various sectors including basic education, school health and nutrition, early childhood development, child protection and livelihoods. The programme is privately funded through three members of Save the Children International (Save the Children US, Save the Children Korea and Save the Children Italy) in support of the local government.

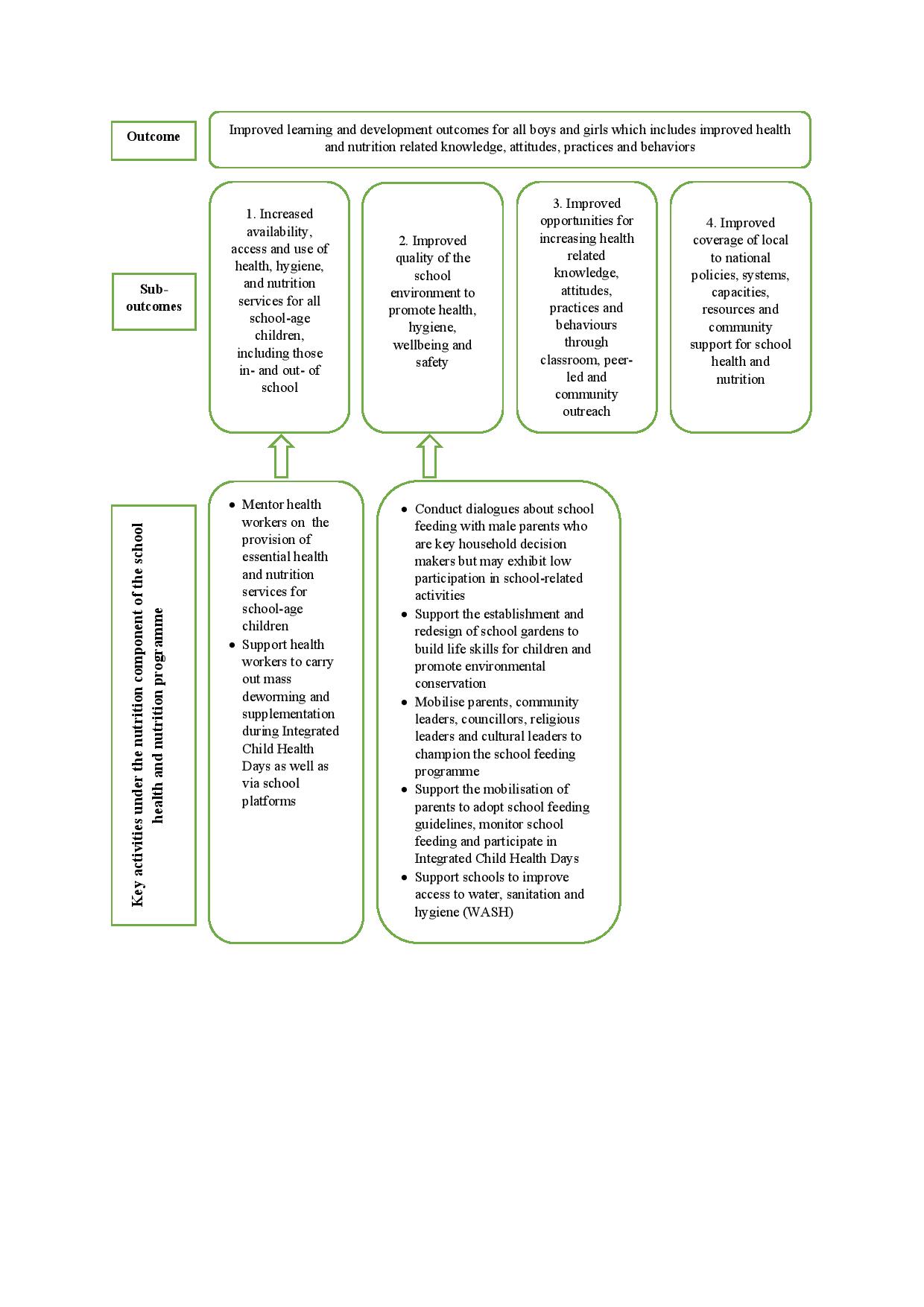

The main aim of the school health and nutrition programme is to improve learning and development outcomes for all boys and girls including improved health and nutrition-related knowledge, attitudes, practice and behaviours. Key activities within the nutrition component specifically contribute to the following sub-outcomes (Figure 1):

- Sub-outcome 1: Increased availability, access and use of health, hygiene and nutrition services for all school-age children including those in- and out- of school

- Sub-outcome 2: Improved quality of the school environment to promote health, hygiene, wellbeing and safety

Figure 1: Key activities under the nutrition component of the school health and nutrition programme

The overarching programmatic framework is the Focusing Resources on Effective School Health (FRESH) framework1 which provides the foundation for developing effective school health programmes and incorporates the following components (programme pillars): (1) equitable school health policies; (2) safe learning environments; (3); skills-based health education; and (4) school-based health and nutrition services.

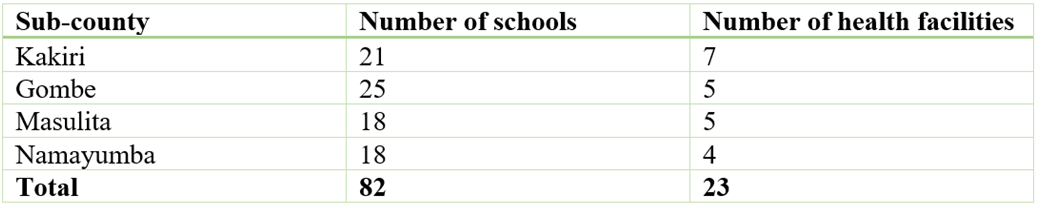

Since 2018, the school health and nutrition programme has supported the local government to improve the delivery of nutrition services in 82 government-owned primary schools which represent 32% of the schools in Wakiso District, reaching a total of approximately 37,358 children (17,313 girls and 20,072 boys). These schools fall under the catchment area of 23 health facilities in four sub-counties (Table 1).

Table 1: Schools and health facilities supported, by sub-county

Sub-outcome 1: Availability, access and use of health, hygiene and nutrition services for in- and out- of school children

Under sub-outcome 1, the programme supports the 23 associated health facilities to provide essential health and nutrition services through the provision of nutrition assessment and counselling guides as well as conducting needs assessments for health workers and supporting capacity-building within government health structures. The programme also supports community outreach by health facilities, including the bimonthly community outreach activities and child health days, during which children are targeted with comprehensive services such as deworming and vitamin A supplementation. While the programme primarily targets children in school, an inclusive approach is taken to ensure that outreach services are provided to all children in- and out-of-school.

Sub-outcome 2: Improved quality of the school environment

Under sub-outcome 2, community structures, e.g., school management committees (SMCs) and parent-teacher associations (PTAs), are engaged to roll out the parent-led school feeding programme to improve the quality of the school environment. Within schools, the capacity-building of school managers focuses on accountability and the management of funds for school feeding as well as needs assessments and the training of teachers who act as patrons of the programme’s school health clubs. School health clubs meet between monthly and three times per term with the aim of planning activities, sharing information and tracking the progress of activities aimed at promoting good health, WASH and nutrition practices in the schools.

In addition to the in-cash or in-kind school feeding they provide, parents/guardians are sensitised and encouraged by the programme team to provide children with something to eat before they go to school. Parents also lead initiatives to increase their children’s access to sustainable, diverse foods such as implementing and maintaining school gardens. The Community Action Cycle, a seven-stage model for community mobilisation developed by Save the Children, is leveraged to support SMCs and PTAs to develop more sustainable solutions for increased access to, and the availability of, health and nutrition services for school-going children. In particular, schools are supported to improve access to WASH.

Monitoring, evaluation, accountability and learning system

Routine monitoring of outputs and outcomes is conducted on a monthly, quarterly, biannual and annual basis to inform programme reviews and reporting to the district local government, funders and other stakeholders. Quality benchmarks are monitored during implementation with outputs monitored on a termly basis (in March, July and November).

At baseline, a situation analysis was conducted to identify priority problems and opportunities as a basis for developing tailor-made interventions (Save the Children, 2015). Data collection included (1) a review of existing education policies, the Wakiso District development plan, sub-county development plans and other situational analysis reports; (2) interviews and focus group discussions with children, parents and teachers; (3) observations of schools; and (4) a Quality Learning Environment assessment in 15 primary schools. The Baana programme midline evaluation, conducted in August 2019, collected cross-sectional quantitative and qualitative data from 40 schools to assess the degree to which the sub-outcomes had been achieved over the five years of implementation (2015-2019). An endline evaluation is planned for the end of the project.

Key performance indicators and other findings are reviewed in regular project monitoring, evaluation, accountability and learning (MEAL) meetings to inform decision-making and allow for real-time programme adjustments. Learning is guided by Save the Children Uganda’s online issues tracker and the MEAL dashboard which feed information directly into area office and senior management meetings. Special surveys may also be conducted in cases where specific implementation issues need to be explored. For instance, a survey on the parent-led school feeding programme is planned in 2021.

Results

Services for in- and out- of school children

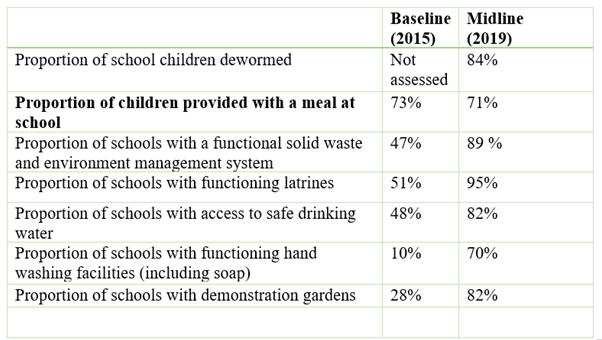

Midline survey results indicated that 73% of schools had a memorandum of understanding with health facilities to inform their collaborative efforts in supporting children with health and nutrition services. This had increased from only 10% of schools at baseline. In addition, at midline, 84% of children in programme-supported schools had accessed deworming services (Table 2).

Parent-led school feeding

At baseline, one of the main reasons for school dropout was the failure of parents to meet the schools’ requirements for the payment of school meals. The midline evaluation highlighted parents’ involvement in contributing to school meals and parents from nearby communities found that schools that were able to provide a midday meal to children were more attractive. Despite this, the proportion of children who were provided with a meal at school did not increase at midline but stagnated at around 71% from 73% at baseline (Table 2). Of those children who received porridge at school, 61% reported that this was the only meal they had in a day. However, in schools that were more effectively implementing school meals, this was shown to improve attendance and children reported being more motivated to attend school so as not to miss the porridge provided. Additionally, 78% of children reported being given something to eat at home before coming to school in the morning during the midline assessment. By 2020, 94% of schools had a school feeding programme/policy in place and 83% of schools had adapted the school feeding guidelines.

School gardens

Observational data showed that the percentage of schools with school gardens increased from 28% to 82% between baseline and midline (Table 2). Many of these were demonstration gardens being used to demonstrate good agricultural practices to parents and boost child feeding at home. In addition, 28 schools (34%) had functional school gardens for school feeding and were growing vegetables and fruit trees (programme outcome monitoring report quarter 1, 2021). According to the project monitoring reports, the number of schools with functional school gardens, not just demonstration gardens, had increased to 71 (88%) by the end of quarter one, 2021. Of those schools that did not have functional school gardens, the reasons included lack of land, the challenges of animals grazing on school land or still being in the planning phase. In 2021, 85% of schools with functional school gardens reported having harvested food for the school feeding programme although yields varied widely between schools.

While many parents engaged with the school gardening activities, 27% of schools reported that parents were opposed to children participating in school gardening. Of those with school gardens, 14% of schools had received quarterly support from an agricultural extension officer (programme outcome monitoring report quarter 1, 2021).

WASH services

At baseline, only 48% of schools had access to safe potable (drinking) water and 10% had handwashing facilities with soap. The quality of the school environment improved substantially from baseline to midline with access to safe drinking water reaching 82% and the availability of hand washing facilities reaching 70% at midline (Table 2).

The proportion of schools with recommended sanitation facilities also increased from 51% at baseline to 95% at midline (Table 2). Improvements were a result of the deliberate engagement of parents in mobilising resources for WASH facilities including setting up low-cost handwashing facilities such as tippy taps, water storage and waste disposal.

Table 2: Key performance indicators

Data source: Baseline (2015) and Midline evaluation (2019)

Data source: Baseline (2015) and Midline evaluation (2019)

Successes and challenges

What went well and why

High coverage of nutrition-specific activities has been achieved for children in programme supported schools. This has been made possible through fostering strong collaborative linkages between the education (schools) and health (health facilities) sectors with schools being prioritised as outreach sites for Integrated Child Health Days.

Community engagement through the community action cycle and engagement with the school management committees has contributed to parents’ involvement in the school health and nutrition programme activities. Parents’ awareness of the school feeding guidelines has been increased through popularising the guidelines using print and audio media, parents are involved in monitoring school gardens and community dialogues with male parents have increased male involvement in the nutrition of children at household level. There have also been improvements in school environments with increased access to WASH facilities.

Challenges and mitigation measures

Social determinants

Social determinants at household level, such as poverty, affect parental uptake of school feeding due to a lack of cash or food available to meet the schools’ requirements. The programme integrated nutrition-sensitive livelihood activities such as using the parent-teacher association platforms to train parents in soap making. Soap making expands income generating opportunities for poor households that could translate into the purchase of food as well as promoting practices like handwashing.

Limited institutionalisation of the school feeding programme

Although school feeding programmes are gradually being institutionalised at school level, there is a limited commitment of resources for ongoing capacity-building and follow up at district level. In some of the programme supported schools, school heads, whose capacity as focal persons had been built by Save the Children, were transferred out, creating a gap in continuity. Save the Children has continued to conduct trainings for new school feeding programme focal persons while advocating for more resource commitments from the local government.

COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic led to repeated, country-wide disruptions in the school calendar because of protracted school closures. This affected activity implementation especially in light of the further movement restrictions that limited the ability of parents and teachers to monitor the school gardens. The programme therefore targeted more resources towards COVID-19 adaptations mainly around improving school readiness for reopening.

Community ownership

Community ownership of the school feeding programmes was a challenge and still needs to be improved. Due to misconceptions around education policies, communities perceive school feeding as the sole responsibility of the government. The school health and nutrition programme is focused on increased community level advocacy and sensitisation to highlight the important role that parents and communities can play in ensuring school feeding programmes are effective and functional – and building their capacity to fulfil this role.

Lessons learned

Favourable policy and guideline frameworks at the national level are critical building blocks to drive school-based nutrition programmes at a sub-national level. The programme has demonstrated how the MoES’s guidelines on school feeding can be operationalised by schools and districts while documenting challenges and lessons learned to inform implementing organisations and other districts across the country.

The use of multi-sector platforms for advancing school-based nutrition programmes can increase buy-in and support for these programmes. The programme has focused on community engagement, leveraged agricultural extension workers and has cross-trained both education and health technical officers such as teachers, health assistants and health inspectors to increase input from multiple stakeholders into the school-based nutrition programme.

The rapid uptake and institutionalisation of school-based nutrition programming is most feasible at the school level especially when existing structures such as SMCs and PTAs are engaged and involved. Schools are able to allocate resources towards school-based nutrition once buy-in has been achieved. At higher levels of the education system, such as the district level, evidence generation and advocacy need to be prioritised to accelerate the long-term sustainability of these programs.

Conclusion

The Save the Children programme has a memorandum of understanding with the local government that stipulates the roles and responsibilities of each party with a view to ensuring the sustainability of the interventions. However, there is a need for the programme to work more closely with local government structures to define key transition targets and align these with government planning and budgeting cycles. Local structures have been empowered to drive interventions on school-based nutrition while promoting sustainability and ownership at the implementation/school level.

This programme has demonstrated that parent-led school feeding programmes are feasible in resource constrained contexts and achieve positive results. Enabling factors include collaboration across the health, education, agriculture and livelihood sectors, the availability of school feeding guidelines and the capacity-building of stakeholders through dialogues and training to enable them to fulfil their unique roles in the school feeding programme.

For more information, please contact Lorna Muhirwe at: lorna.muhirwe@savethechildren.org.

1FRESH is an inter-agency framework developed by UNESCO, UNICEF, WHO and the World Bank that was launched at the Dakar Education Forum in 2000 to incorporate the experience and expertise of these and other agencies and organisations. It is a global framework for improving the health of school children and youth.

References

Best, C, Neufingerl, N, van Geel, L, van den Briel, T and Osendarp, S (2010) The nutritional status of school-aged children: why should we care? Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 31: 400–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482651003100303

Barugahara, EI, Kikafunda, J and Gakenia, WM (2013) Prevalence and risk factors of nutritional anaemia among female school children in Masindi district, western Uganda. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development. 13(3). https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajfand/article/view/90598

Global Nutrition Report (2020) Country profiles: Uganda. Available at: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/eastern-africa/uganda/

Uganda Legal Information Institute (2008) The Uganda education (pre-primary, primary and post-primary) act 2008. Available at: https://old.ulii.org/ug/legislation/act/2015/13

National Planning Authority (2020) Third National Development Plan 2020/21 – 2024/25. Available at: http://www.npa.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/NDPIII-Finale_Compressed.pdf

Save the Children (2019) Evaluating outcomes of Child Sponsorship Program in Wakiso district, Uganda: midline evaluation report. Available at:

Save the Children (2021) Project Outcome Monitoring Report Quarter 1, 2021