Addressing child wellbeing among ‘skip-generation’ households in Cambodia

This article outlines an innovative approach that targets grandmothers to improve child nutrition outcomes among Cambodian skip-generation households. Skip-generation households are families where grandparents raise children while parents are absent from the household.

Sarah Bauler, Senior Advisor, Nutrition Design, Evaluation and Research, World Vision (WV) International

Kathryn Reinsma is a Senior Nutrition Technical Advisor, WV International

Grana Pu Selvi is the Technical Lead, Integrated Nutrition, WV International, Cambodia

Carmen Tse is a Nutrition Technical Advisor, WV International

Todd Nitkin is a Global Senior Advisor, Health Design, Evaluation and Research, WV International

Munint Mak is a Senior Technical Specialist, Integrated Nutrition, WV International, Cambodia

|

Location: Cambodia Key Messages:

|

Background

Between 2010 and 2016, Cambodia experienced a substantial economic expansion largely driven by the garment industry, tourism sector and a construction boom in the capital city, Phnom Penh. The garment sector provides an important source of income and employment in Cambodia; nearly one in five women in Cambodia are employed in that sector (IOM, 2020). On average, most garment factory workers are under the age of 35 and originate from the Cambodian provinces, with Kampong Speu and Kampong Chnhang providing the third-highest number of workers behind Phnom Penh and Kandal (ILO, 2018).

Since the early 1970s, World Vision has implemented a diverse range of relief and development programmes in Cambodia including integrated nutrition, quality of education for young children and child protection programming, to improve child wellbeing outcomes especially for the most vulnerable children. One critical measure of vulnerability among children is the employment status of their caregivers. In Kampong Speu and Kampong Chhnang provinces, where World Vision works, the majority of mothers commute daily to Phnom Penh and other provinces to work in garment factories. These mothers work an average of 60 hours per week for only 93 cents per hour – roughly USD220 per month (Bauler, 2020). Most of these mothers are between the ages of 17 and 35, the prime child-bearing and caring ages for women. Because commuting mothers are absent from the household for an average of nine to 12 hours per day, many grandmothers have been forced to assume the role of primary caregiver (Reinsma, 2020). Households where grandparents raise their grandchildren due to parental absence can be referred to as skip-generation families.

These increased childcare responsibilities for grandmothers have increased the risk of poor health outcomes and inequities among children and the grandmothers themselves. While many families depend on the income generated by garment work, this has led to poor breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices. From key informant interviews (KIIs), we learned that new mothers return to work shortly after giving birth due to poorly enforced maternity leave policies and the fear of having their position replaced by another woman (Bauler, 2020). Hence, children of garment factory mothers have little opportunity to be exclusively breastfed until six months of age as recommended by the World Health Organization. Of 266 garment factories in Cambodia, only 43 (19%) have functioning day-care centres at or near the factory (ILO, 2015).

Poor infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices among children of skip-generation households can increase the risk of child malnutrition. This is already a significant issue in Cambodia where 32% of children under five years of age are stunted, 24% underweight and 10% wasted (Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey, 2014). These alarming rates of malnutrition reveal an equity gap in Cambodia as stunting is more common in rural (34%) than urban areas (24%) and is less common among children of higher educated mothers (Child Rights Now, 2018). This phenomenon is also present in Kampong Speu and Kampong Chhnang provinces as these areas are more rural and have higher illiteracy rates than World Vision-supported urban provinces.

To address these health inequities, World Vision implemented the Grandmother Inclusive Approach Project to build the knowledge, skills and behaviours of grandmothers with primary caregiving responsibility for children younger than two years old. This article shares the results that this programme had on IYCF and child wellbeing outcomes.

The Grandmother Inclusive Approach (GMIA) Project

World Vision adapted the ‘Grandmother Project: Change through Culture’ approach, a contextualised programme that builds upon the culturally designated role of grandmothers as the key influencers of childcare practices. This innovative approach, used previously in other World Vision contexts, was adapted to the Cambodian context as the GMIA Project to build the knowledge, skills and behaviours of grandmothers responsible for the primary care of children due to the prolonged absences of mothers for employment in garment factories. The approach also sought to alleviate grandmothers’ stress by facilitating community dialogues and building social support systems to address the issues related to shifts in childcare roles within the household due to the employment of the mothers or migration of the parent/s.

World Vision Cambodia piloted the GMIA Project in Basedth (rural) in Kampong Speu Province, Samrong Tong (rural) in Kampong Chhnang province and Phnom Penh (urban) area programmes to see if the approach improved IYCF practices and child wellbeing outcomes. The project was implemented from October 2020 to October 2021 and it targeted 632 grandmothers and 52 grandmother groups were formed. In addition to the monthly grandmother health and nutrition promotion sessions, intergenerational meetings were conducted to encourage family members to share the workload placed upon grandmothers. To our knowledge, World Vision is the first organisation to use this approach in a context where there is significant prolonged absence by mothers due to work.

A quantitative baseline survey was conducted in July 2020 in World Vision’s Basedth, Phnom Penh and Samrong Tong area programmes to determine IYCF outcome-level indicators. Selection criteria for the survey respondents included grandmothers with children under two years of age where the grandmother was the primary caregiver. A sample size of 300 grandmothers was selected to provide a 95% confidence level to detect a 10% or greater change in baseline and final indicators, assuming a 10% non-response rate. A two-stage probability sampling procedure was used to identify childcare knowledge, beliefs and practices among grandmothers and assess their self-efficacy and perceived level of stress and anxiety. Data was collected on tablets using Open Data Kit, transferred to Excel and then analysed using SPSS version 25. Chi-square statistical tests were used to analyse categorical outcome and demographic indicators and paired-sample t-tests were used to analyse continuous demographic indicators and the psychological distress score. The final evaluation (endline survey) replicated the baseline survey methodology and was conducted in October 2021.

Results

Demographics

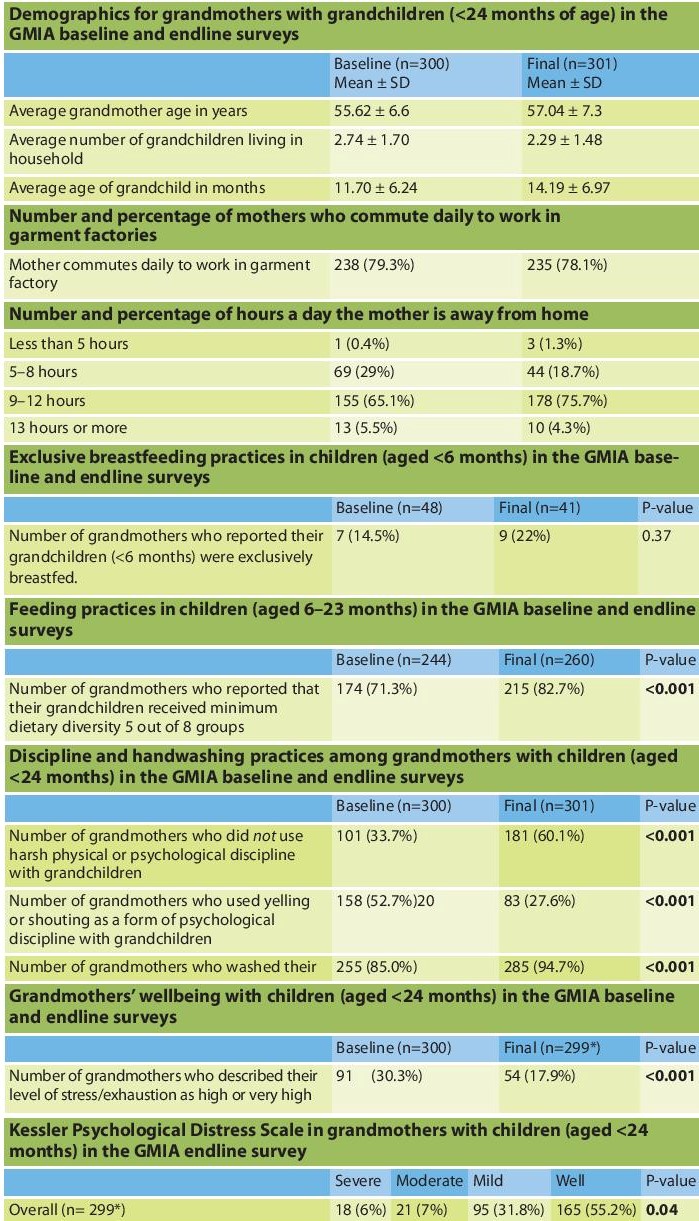

Table 1 details the demographic characteristics of the grandmothers who participated in the GMIA Project. Of the grandmothers who were sampled at baseline, the average age was just above 55 years whereas at endline the average age was slightly older at 57 years. At endline, there were slightly fewer grandchildren living in the house (2.74 children at baseline, 2.29 children at endline) and the children were slightly older (11.70 months at baseline, 14.19 months at endline). Nearly 80% of mothers in Basedth, Phnom Penh and Samrong Tong World Vision Area programmes commuted daily to work in garment factories (79.3% at baseline, 78.1% at endline). Of those mothers who commuted daily to work in garment factories, the majority were away from the home between nine to 12 hours per day (65.1% at baseline, 75.7% at endline).

Infant and young child feeding practices

When measuring IYCF practices, only 14.5% of children aged zero to five months were exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life at baseline and 22% at endline (Table 1); there was no significant increase from baseline. The exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) rates were far lower than the country average (73%), possibly illuminating the health inequities and outcomes between skip-generation households and the broader population (Alive and Thrive, 2018).

Minimum dietary diversity (MDD) for children aged six to 23 months of age was based on the number of grandmothers who said their grandchild had eaten food from at least four different food groups the previous day. Food groups included dairy, grains, vitamin A-rich vegetables, other fruits/vegetables, eggs, meat/poultry/fish, legumes/nuts, oils/fats and breastmilk (MDD, Table 1). The proportion of grandmothers who reported their grandchildren aged six to 23 months had received MDD significantly increased from 71.3% at baseline to 82.7% at endline (p<0.001).

Child care practices

There is evidence that increased levels of stress among caregivers is associated with higher levels of child maltreatment (Rodriguez-JenKins & Marcenko, 2014). At baseline, of the grandmothers who reported any use of harsh or psychological discipline with children, shouting or yelling was the most common at baseline and endline but decreased from 52.7% to 27.6% (Table 1). At endline, significant improvements around child discipline practices were found. The proportion of grandmothers who had not used harsh physical or psychological discipline with their grandchildren in the previous two weeks increased from 33.7% at baseline to 60.1% at the end of the project (p<0.001). No significant associations were found when testing the relationship between a grandmother’s stress levels and the use of harsh or psychological discipline. Harsh and psychological discipline was defined as shouting or yelling at the child, calling a child a derogatory term and shaking, spanking, slapping or hitting a child.

Handwashing with soap, especially among caregivers of small children, is a critical determinant for achieving and maintaining good child nutrition. Over 50% of cases of child undernutrition are associated with repeated diarrhoea or intestinal infections as a result of unsafe water, inadequate sanitation or insufficient hygiene (Prüss-Üstün, 2008). The proportion of grandmothers who washed their hands at appropriate times with soap significantly improved from 85.0% at baseline to 94.7% at endline (p<0.001).

Levels of stress among caregivers

Maternal garment factory work appears to place grandmothers’ wellbeing under additional stress as they assume increased childcare responsibilities. The proportion of grandmothers who described their level of stress as high or very high decreased from 30.3% at baseline to 17.9% at endline (p<0.005). During KIIs, community development facilitators and community volunteers said that the parents who participated in the programme knew that grandmothers worked hard but they had no other choice but to leave their children in their care because they had to earn an income. They noted that the programme helped to improve the perception of grandmothers, recognise their work and improved relationships among family members. In some cases, mothers and fathers said they were now buying food/clothes for grandmothers and giving them time to attend GMIA meetings or do something they wanted to. One community volunteer from Samrong Tong said, “Previously only grandmothers care for children, but right now grandfathers can help and assist grandmothers in taking care of the children.”

At endline, we also used Kessler’s Psychological Distress Scale (KPDS) to better understand this issue and to build the practice of utilising the KPDS in Cambodia. Among the 299 grandmothers who participated in the endline survey, 6% (n=18) suffered from severe psychological distress and 7% (n=21) from moderate psychological distress and anxiety. Overall, more than half (55.2%) of grandmothers scored in the well category (Table 1).

Table 1: Comparison of findings from baseline to endline

* Two grandmothers opted out of this final stage of the questionnaire

Discussion

Our approach was successful in improving some critical childcare practices including MDD, handwashing and the decreased use of harsh child discipline. Rates of EBF did not improve but this can be expected given that nearly 80% of grandmothers reported their daughter/daughter-in-law worked in garment factories for more than nine hours a day. When determining the barriers to EBF, upstream determinants of IYCF practices should also be taken into consideration. Global economic forces fuel the garment industry which has led to the unequal distribution of income, power and wealth among Cambodian factory workers. The Cambodian government has protection for working mothers in its 1997 Labour Law (amended in 2007), guaranteeing paid maternity leave for 90 days with 50% wage compensation as well as other conditions to support childcare and breastfeeding in the workplace. However, poor enforcement of policies, as well as cultural values and norms around gender, perpetuate gender inequities in the workplace and at home. These underlying causes of health inequalities and injustices lead to poorer wellbeing among children and caregivers living in households with garment factory workers (IOM, 2019).

A child’s nutritional status is often intrinsically linked to the physical and mental wellbeing of the caregiver. A recent study evaluating grandparent caregiving in Cambodian skip-generation households found that grandparents often face difficult moral and ethical dilemmas trying to balance caregiver responsibilities and caring for their own health needs (Schneiders, 2021). Our study has shown that utilising validated tools to measure programme impact on decreasing caregiver stress and psychological wellbeing can be integrated into data collection tools. Including evidence-based tools to measure and treat caregiver depression to improve child wellbeing could be significant, as a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that stunting could be reduced globally by about 27% by eliminating maternal depression (Slomian, 2019).

Our baseline and endline surveys, complemented by other research, reveal the challenges that skip-generation households face in providing desired childcare practices. The GMIA Project improved some critical childcare practices such as dietary diversity and caring practices related to child discipline methods and decreased levels of perceived stress among grandmothers. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the project to support grandmothers’ caregiver capacity due to shifts in household responsibilities. However, EBF rates did not significantly improve showing that additional actions and investment are needed to address upstream factors of poor child wellbeing outcomes. Garment factories must enforce government-issued maternity policies and be held accountable to uphold these policies which would allow more mothers to spend at least the first few months with the child and exclusively breastfeed the child without the fear of losing their jobs. It is likely possible to improve IYCF programming by complementing behavioural (downstream) interventions with nutrition advocacy and strategies that address the political (upstream) determinants of undernutrition.

Conclusion

In summary, we recommend the following three actions when addressing poor child wellbeing in skip-generation households:

- Utilise tailored strategies, such as the GMIA Project, to target grandmothers as primary caregivers in skip-generation families.

- Consider including strategies to measure and address the social-psychological needs of grandmothers in skip-generation families to improve child nutrition outcomes.

- Develop strategies to address the political (upstream) determinants of poor child nutrition – either through partnership with other organisations or through internal organisational advocacy – as factors that have led to skip-generation households are often rooted in social injustice and health inequity.

We hope this article has deepened the readers’ understanding of the nutrition-related roles that grandmothers play in skip-generation households in Cambodia and provided clear recommendations for how policies and interventions can be designed to address these unique challenges.

For more information, please contact Sarah Bauler at sarah_bauler@wvi.org or Kate Reinsma at kate_reinsma@wvi.org

References

Alive and Thrive (2018) The cost of not breastfeeding in Cambodia. https://www.aliveandthrive.org/sites/default/files/attachments/AT_CONB-Brief-Cambodia.pdf

Bauler S (2020) Cambodia PDH mHealth study project field visit report. World Vision internal report.

Bauler S and Davis T (2020) Why we should care more about caregiver mental health and its impact on child wasting. The State of Acute Malnutrition. https://acutemalnutrition.org/en/blogs/mental-health-wasting

Cambodia Demographic Health Survey (2014) https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr312/fr312.pdf

Care International (2016) Women in Cambodia’s garment industry. https://www.care.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/SHCS_Brief-Women-Cambodia-Garment-Industry-March-2017_CA.pdf

Child Rights Now! (2018) Unlocking Cambodia’s future by significantly reducing rates of malnutrition. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Policy%20Brief%204-Mulnutrition-06Nov.pdf

International Labor Organization (2015) Practical challenges for maternity protection in the Cambodian garment industry. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/---sro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_203802.pdf

International Labor Organization (2018) Living conditions of garment and footwear sector workers in Cambodia. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_663043.pdf

International Labor Organization (2020) The supply chain ripple effect: How COVID-19 is affecting garment workers and factories in Asia and the Pacific. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/documents/briefingnote/wcms_758626.pdf

International Organization for Migration (2019) Migration impacts on Cambodia children and families left behind. International Organization for Migration. https://www.louvaincooperation.org/sites/default/files/2020-08/Migration%20impacts%20on%20cambodian%20children-MHICCAF%20REPORT.pdf

Grandmother Inclusive Approach (2021) World Vision International. https://www.wvi.org/nutrition/grandmother-approach

Grandmother Project: Change Through Culture (2020) https://grandmotherproject.org/

Prüss-Üstün A, Bos R, Gore F, Bartram J (2008) Safer water, better health: costs, benefits and sustainability of interventions to protect and promote health. World Health Organization. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43840/9789241596435_eng.pdf;jsessionid=A32E8A682E38D253E55B72FE86D610AE?sequence=1

Reinsma K (2020) Cambodia grandmother inclusive approach baseline report. World Vision internal report.

Rodriguez-JenKins J and Marcenko M (2014) Parenting stress among child welfare involved families: Differences by child placement. Children and Youth Services Review, 2014;46, 19-27.

doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.07.024

Schneiders, M (2021) Grandparent caregiving in Cambodian skip-generation households: Roles and impact on child nutrition. Maternal and Child Nutrition. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/mcn.13169

Slomian J et al. (2019, April) Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: a systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes Women’s Health.