Cash transfers and health education to address young child diets in Kenya

Chloe Angood is a Knowledge Management for Nutrition Consultant for the UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO)

Penjani Kamudoni is a Nutrition Specialist for the UNICEF Kenya country office

George Kinyanjui is a Social Policy Specialist for UNICEF Kenya country office

This article is based on a case study prepared by UNICEF’s Eastern and Southern Africa regional office (ESARO), led by Chloe Angood for UNICEF ESARO, in collaboration with Annalies Borrel (UNICEF Headquarters Nutrition Section), Tomoo Okubo (UNICEF Headquarters Social Protection Section), Mara Nyawo and Christiane Rudert (UNICEF ESARO Nutrition Section) and Tayllor Renee Spadafora (UNICEF ESARO Social Protection Section). We thank the Kenya UNICEF country office nutrition and social protection teams who shared their insights and experiences, including Penjani Kamudoni, George Kariuki Kinyanjui, Humphrey Mosomi, Susan Momanyi and Ana Gabriela Guerrero Serdan. The documentation of this case study was supported by thematic funding from the Government of the Netherlands.

|

Key messages:

|

Background

Improving the diet of young children through linked cash and nutrition programmes

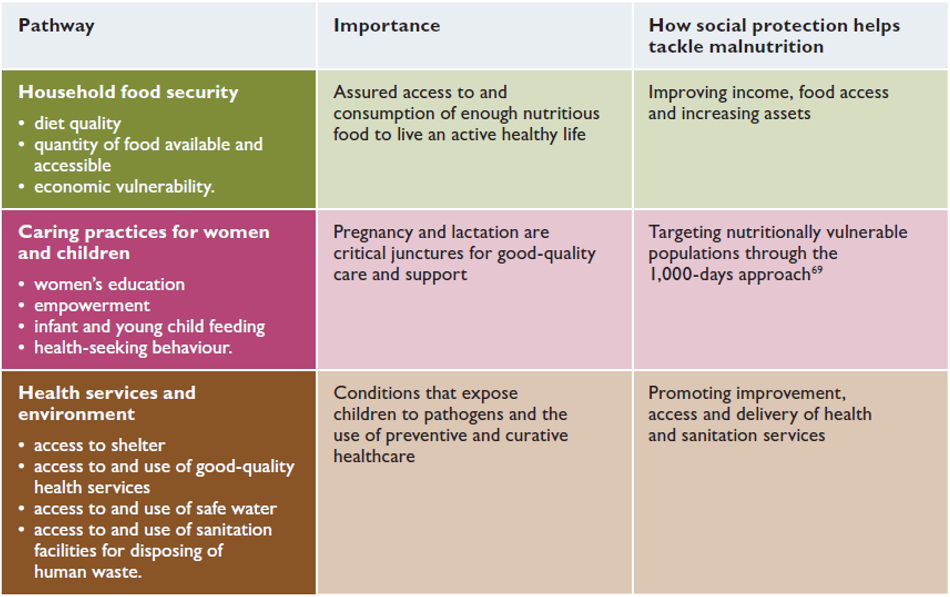

Social protection is a key delivery system for improving nutrition because social protection interventions such as cash transfer programmes, by improving income and increasing assets, have the potential to empower female caregivers, increase access to and availability of diverse foods, increase uptake of positive nutrition practices and improve access to nutrition and other services (Table 1). These are critical factors along the impact pathway to improved child diets, childcare and, ultimately, improved nutrition. For this reason, increasing the “nutrition sensitivity” of social protection interventions is a key priority for improving the diet of young children, as laid out in UNICEF’s complementary feeding guidance (UNICEF, 2020). Recent evidence suggests that cash transfer programmes can reduce child stunting, wasting and diarrhoea incidence, although the effects are heterogenous and small overall. The effects of increasing the consumption of animal source foods, improving diet diversity, and reducing diarrhoea incidence have been more pronounced (Manley et al., 2022). Cash transfers are more likely to improve the diet of young children if they are accompanied by complementary interventions, or “cash plus” elements, such as behaviour change communication (BCC), and if they link participants to other services such as health and livelihoods (Manley et al., 2022; Little et al., 2021).

Table 1: Pathways of enhancing nutrition through social protection

Nutrition situation of young children in Kenya

As of February 2022, following five consecutive poor seasonal rainfall performances, 3.5 million people residing in Kenya’s Arid and Semi-Arid Lands (ASAL) were severely food insecure. Although the levels of stunting and wasting have fallen in recent years, both remain high at 26% and 7% respectively. While 99% of children are breastfed in Kenya, only 22% of children aged 6–23 months are estimated to receive a minimum acceptable diet (MAD) (KNBS, 2015). This proportion falls to 3% in the highly food insecure North-Eastern region (KNBS, 2015). Poor diet quality is driven by poverty and food insecurity, as well as poor young child feeding and caring practices. To provide a comprehensive solution to this multifaceted problem, integrated social protection and nutrition strategies are required to ensure the optimal growth, development and well-being of young children.

Social protection policy and programmes in Kenya

Much progress has been made in recent years to develop a comprehensive social protection system in Kenya to mitigate poverty among the most vulnerable sections of society. Guided by the 2011 National Social Protection Policy, the current system is arranged around the four pillars of income security (including social assistance), social health protection, shock responsiveness and complementary programmes. The main platform for government social assistance is the National Safety Net Programme (NSNP), managed by the Social Assistance Unit, which targets cash transfers at different stages of the lifecycle (Table 2). The Hunger Safety Net Programme (HSNP), under the National Drought Management Authority (NDMA), targets additional cash transfers at poor households vulnerable to drought in ASAL counties. The HSNP provides a regular bimonthly cash transfer of KES 5,400 (USD 48) to 100,000 households, which is scaled up to over 270,000 households in response to shocks (with planned expansion to more). Under the fourth “complementary programmes” pillar of the social protection system, the government aims to provide a range of complementary programmes in addition to cash transfers to support the development and productive capacity of vulnerable sections of society. The main nutrition intervention under this pillar is the Nutrition Improvements through Cash and Health Education (NICHE) programme.

Table 2: NSNP cash transfers

|

Name of cash transfer |

Recipient criteria |

Benefit level |

Coverage |

|

Older Persons Cash Transfer (OP-CT) |

Any Kenyan citizen above 70 years of age |

KES 2,000 (USD 18) per month |

203,011 individuals |

|

Cash Transfers for Orphans and Vulnerable Children (CT-OVC) |

Poor households caring for orphans or other vulnerable children |

KES 2,000 (USD 18) per month |

246,000 households |

|

Persons With Severe Disability Cash Transfer (PWD-CT) |

Poor households caring for a child or adult living with a severe disability |

KES 2,000 (USD 18) per month |

45,505 individuals |

NICHE pilot programme (2016–18) – Phase 1

In 2016, UNICEF partnered with county governments, with funding from the European Union Supporting Horn of Africa Resilience in Kenya programme, to implement the NICHE pilot. NICHE aimed to bring together relevant government departments and stakeholders to address multiple vulnerabilities in extremely poor households in Kitui County and parts of Machakos County (two counties with very high levels of stunting). The NICHE pilot targeted all households receiving CT-OVC (Table 2) with either a pregnant woman and/or a child under the age of two (3,800 households). In addition to the regular CT-OVC cash transfer, recipients received a bimonthly cash top-up of KES 500 (USD 5) per child and/or pregnant woman for up to two household members (a maximum of KES 1,000, or USD 10, per household) and nutrition counselling. The counselling emphasised iron/folic acid supplementation during pregnancy, exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months, appropriate complementary feeding, vitamin A supplementation, growth monitoring, the use of oral rehydration solution (ORS) when children were sick and kitchen gardening and small livestock production. Community Health Volunteers (CHVs) trained by the Ministry of Health (MoH) delivered the nutrition counselling through weekly household visits. In select areas, child protection group sessions were also delivered by Child Protection Volunteers. By simultaneously providing cash transfers and nutrition and parenting counselling, the project aimed to address the lack of access to nutritious food and poor young child feeding practices to improve the diet of young children.

An evaluation set up as a randomised control trial measured the impact of the programme compared to control households receiving standard CT-OVC cash transfers only. The results showed minimal positive changes in stunting reduction, likely due to the short duration of the project and the multiple drivers of stunting. However, the programme had a strong, significant impact on child diets, demonstrated by a 44% increase in children achieving a MAD. Other indicators along the nutrition impact pathway were also improved, including the treatment of drinking water (+40%), the use of household handwashing facilities (+29%), early initiation of breastfeeding (+8%) and exclusive breastfeeding (+7%) (Guyatt et al., 2018).

Qualitative data revealed that counselling sessions were relevant to participants and that learning translated into changes in infant and young child feeding and livelihoods behaviours, especially planting kitchen gardens and purchasing small livestock. Reported problems included difficulties accessing cash through banks, cash transfer values being too low to make desired changes and communication difficulties with programme implementers and CHVs when problems arose (Guyatt et al., 2018).

Figure 1: Word cloud of households’ most-mentioned words when describing CHV visits (Guyatt et al., 2018)

Expanded NICHE (2019–2022) – Phase 2

Based on findings from the initial pilot, the Government of Kenya (GoK) has now scaled up NICHE in five stunting “hotspot” counties (Kitui, Marsabit, West Pokot, Turkana and Kilifi). This phase is being implemented and funded by GoK, with support from the World Bank and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) for the first five years. UNICEF and partners are providing technical support for the first three years, with a view to full government ownership and implementation from the fourth year onwards.

In this phase, households with a child under the age of two and/or a pregnant woman that are registered to receive any NSNP cash transfer (Table 2) and/or the HSNP are targeted with nutrition counselling and a bimonthly cash top-up of up to KES 500 per beneficiary for up to two household members (a maximum of KES 1,000, or USD 10, per household). Cash top-ups are provided alongside routine payments. Eligible households are identified using NSNP and HSNP recipient lists and validated through a process of community identification with continuous/on-demand registration. A digital management information system was developed within the existing information system for the NSNP and HSNP to support registration and results tracking and to report on performance indicators. The NICHE digital management information system is also interoperable with the Kenya Health Information System.

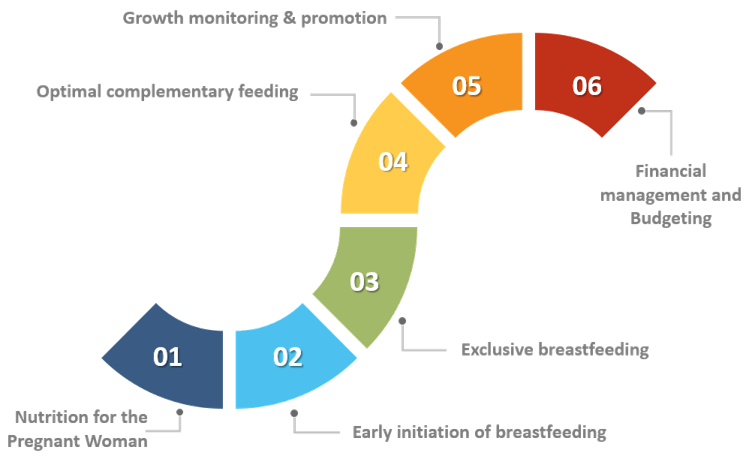

Nutrition counselling is delivered through the Baby Friendly Community Initiative approach, an MoH initiative that aims to strengthen routine community nutrition services. CHVs deliver counselling on a range of topics (Figure 2) during fortnightly home visits, whilst supported by Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs), and mothers also participate in community mother support groups. A social BCC strategy and materials have been developed to support these activities. In Kilifi, NICHE households also receive counselling in positive parenting practices to support child protection outcomes to pilot this approach, with a view to expand this feature to all other participating counties.

Top-up cash payments began in July 2021 to cover the period between March and April of the same year. By the end of 2021, over 12,000 households in 15 sub-counties were enrolled in the NICHE programme? Training has since been rolled out to CHEWs and CHVs, who are now implementing the counselling component. In response to the current food insecurity crisis in programme areas, CHVs have also been trained to provide mid-upper arm circumference screening for the early detection and referral of wasted children.

Figure 2: Nutrition counselling topics in NICHE

Implementation, workforce and delivery mechanisms to support nutrition-sensitive social protection

Several implementation challenges were identified during the evaluation of the NICHE pilot (2016–18). These included difficulties managing programme entry and exit for recipients given the short nature of the target period (from pregnancy up to the child’s second birthday); false reporting of behaviours; CHVs not initially visiting all households (this was improved through closer management); falsification of household reports by CHVs; and out-of-date government information leading to difficulties in identifying eligible households.

Design changes were made to the second phase to overcome these challenges. An improved system for identifying and enrolling recipients is now being used, supported by the new digital information management system, to enable swift programme entry and exit. An operations manual has been developed for programme staff to support standardised as well as enhanced implementation. This also builds the capacity of government field personnel to sustain implementation in the absence of UNICEF technical assistance. The capacity of GoK’s health workforce has also been built by training CHEWs as trainers, who then cascade training to all CHVs in the area.

A formative evaluation of Phase 2 showed high programme performance on the cash transfer side, with funds being transferred regularly and on time. However, there is evidence that the cash transfer value is too small to impact household behaviours. Evidence also suggests the need for further integration between social protection, health and nutrition staff at sub-national levels to fully link cash transfers with nutrition counselling and other sectoral services. This is now being actioned.

Key lessons learned

- Providing cash alongside sustained nutrition counselling has enabled vulnerable populations to adopt positive nutritional practices by raising awareness of, and improving access to, nutritious foods.

- Multi-sectoral coordination bodies at national and devolved levels can help facilitate coordination and integration between health and social protection systems.

- Aligning integrated social protection and nutrition programmes with the strategies of each sector and ensuring complementarity between sector policies and strategies are key enablers of joint programming.

- Joint targeting of social protection and nutrition services depends on strong system linkages at the programme level. This is greatly facilitated by common digital registration and management information systems.

- Programme-level integration between health and social protection can be supported through the comprehensive training of different staff cadres and by providing operational guidance that details specific roles and responsibilities.

- Nutrition-sensitive social assistance programmes are more likely to achieve desired nutrition impact when cash transfers are of sufficient value and paid on time. The social protection system may need strengthening to achieve this, including the preparation of strategies to secure sustainable financing.

- While the social protection system in Kenya has provisions to scale up in response to shocks, the scale of the current food insecurity crisis in the ASAL regions suggests that further system strengthening is urgently needed to avert future nutrition emergencies.

Conclusion and next steps

The NICHE pilot proved to be an effective way to address multiple vulnerabilities in extremely poor and nutritionally vulnerable households in Kenya, with clear evidence that this resulted in improved diets for young children. The scale-up of NICHE is underway. A strong evaluation and learning component, including a cost-effectiveness study, will generate evidence to inform further scale-up and the full integration of the programme into routine systems following this phase. The scale of the current food insecurity crisis in the ASAL regions of the country threatens to reverse these gains and reveals the urgent need to strengthen the capacity of the social protection system to surge in response to shocks. As further climatic shocks become inevitable, further integration of social protection and nutrition, as well as strengthened capacity to scale up support to households both vertically and horizontally, will become central to protecting the diets and growth of young children in Kenya.

For more information, please contact Chloe Angood at cangood@unicef.org.

References

Guyatt H, Klick M, Muiruri F et al. (2018) Final Report: Evaluation of NICHE in the First 1,000 Days of a Child’s Life in Kitui and Machakos Counties, Kenya.

KNBS (2015) Demographic and Health Survey 2014. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Health, NACC, KEMRI, NCPD, Nairobi, Kenya.

Little M, Roelen K, Lange B et al. (2021) Effectiveness of cash-plus programmes on early childhood outcomes compared to cash transfers alone: A systematic review and meta-analysis in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med, 18, 9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003698.

Manley J, Alderman H, Gentilini U (2022) More evidence on cash transfers and child nutritional outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Global Health, 7, e008233.

UNICEF (2020) Improving Young Children’s Diets During the Complementary Feeding Period. UNICEF Programming Guidance. UNICEF, New York.

1 http://www.socialprotection.or.ke/ (accessed 19 January 2022)