In Yemen, Cash Assistance Contributes to Positive Nutritional Outcomes

Tammam Ahmed is a Nutrition Specialist at Save the Children International

Main Chowdhury is Director of Programme, Development, and Quality at Save the Children International

Amer Bashir is Head of Health and Nutrition at Save the Children International

This work would not have been possible without the financial support of the Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations. We are especially indebted to the Save the Children country office MEAL and Hajjah Health and Nutrition programme teams, who have been supportive of this learning and who have worked actively to provide essential data to pursue this article. We are grateful to all of those with whom we have had the pleasure to work with while preparing this publication.

|

Key messages:

|

The Yemen crisis

The humanitarian crisis in Yemen remains the worst in the world. Six years of conflict have brought economic collapse, and the continuous breakdown of public institutions is driving the country to the brink of famine, exacerbating needs in all areas. In north-western Yemen, along the Red Sea, the Hajjah governorate is particularly in need of humanitarian support. While hostilities are subsiding, the area is home to comparatively high numbers of children affected by severe wasting.

In 2019, in response to the deteriorating nutrition, health and food security situations, Save the Children implemented an integrated multi-sectoral programme to enhance access to quality primary health, nutrition and child protection services in three districts of the Hajjah governorate: Ash Shagadirah and Bani Qais districts in the Lowlands, and Kuhlan Affar district in the Highlands. Unconditional cash assistance was provided to families with children who had successfully recovered from severe wasting.

This article is based on an analysis of performance indicators comparing the time when no cash transfer was in place and the same indicators during the time the cash component was introduced.

Programme context and justification

Nutrition situation

Data from nutrition surveys using the standardised monitoring and assessment of relief and transitions (SMART) methodology show that all malnutrition levels have been incredibly elevated among children aged 6–59 months since 2015 in the Hajjah governorate. In 2018, before the programme started, wasting affected up to one out of every seven children (14.9%) in the districts of Bani Qais and Ash Shaghadirah, while this proportion was less severe in Kuhlan Affar district (just below 10%). Stunting levels were extremely high in the three districts: 53.3% in Bani Qais and Ash Shaghadirah districts, and 55.2% in Kuhlan Affar district (ACF, 2018).

Child feeding practices were of particular concern in 2018, according to survey data (ACF, 2018). Only 17.6% of the children below the age of five months were exclusively breastfed in the Lowlands, and only 30.3% in the Highlands. In terms of minimum dietary diversity, only 11.9% of children aged 6–23 months had received foods from four or more food groups during the previous day in the Lowlands; the same proportion was 9.1% in the Highlands. The minimum acceptable diet among children six to 23 months was 7.1% in Lowlands and 4% in the Highlands. Poor water, hygiene and sanitation (WASH) facilities and practices, as well as a stretched health system, contributed to the high levels of malnutrition. Very few humanitarian partners operated in the Hajjah governorate to provide support to the population.

Food security and livelihoods

Armed conflict remains the main driver of food insecurity in Yemen, curtailing food access for both the displaced and host communities. The food security crisis was further exacerbated by extremely high food prices, the liquidity crisis, disrupted livelihoods and high levels of unemployment. The large food gaps were only marginally mitigated by the household food distributions, which were inadequate to reverse the continuous deterioration of the situation. Food insecurity was more severe in areas with active fighting and particularly affected internally displaced people and host families, marginalised groups and landless wage labourers, who faced difficulties in accessing basic services and conducting livelihood activities.

According to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) analysis, approximately 1.6 million people (66% of the Hajjah governorate population) were in Phase 3 or higher for the period covering December 2018 to January 2019 (IPC, 2018). This was projected to increase to almost 1.9 million people (78%) if no household food assistance (HFA) was provided to the population.

The analysis of a food consumption proxy indicator1 showed that 52% of households in the Lowlands livelihood zone and 43% of those in the Highlands livelihood zone were categorised as having either a “poor” or a “borderline” food consumption. Half of the households from both the Lowlands (50.3%) and the Highlands (49.7%) used at least one form of coping mechanism to manage the fact that they had not had enough food or money to buy food over the previous seven days (ACF, 2018).

Programme outline

A Save the Children multi-sectoral programme was initiated in April 2019 in 16 health facilities. It adopted the “Minimum Service Package” – endorsed at national level by the Ministry of Public Health and Population and both the Health and Nutrition Clusters – to support the delivery of integrated primary health, treatment of malnutrition and preventive services and child protection services. The programme also supported community outreach activities, including case finding, referrals and health promotion and awareness sessions, to reach the most vulnerable populations in the targeted areas.

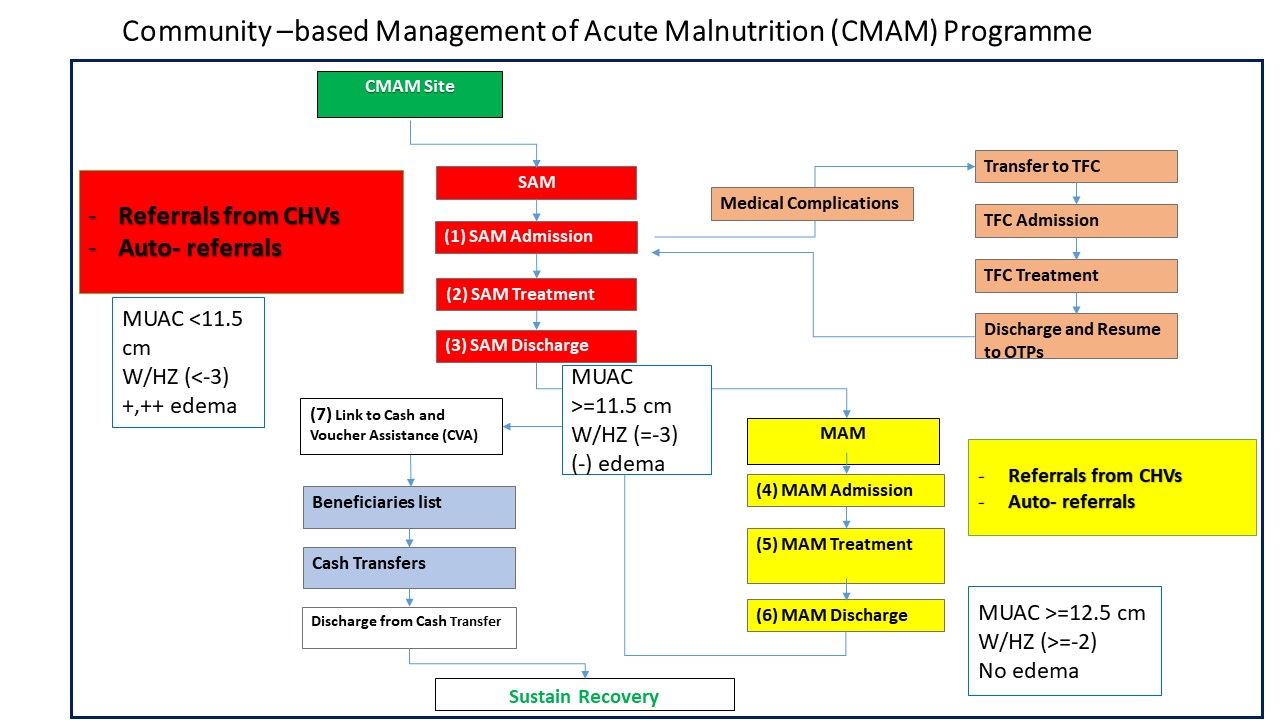

Since the programme’s inception, the nutrition component had focused on ensuring access to wasting treatment services among children under the age of five and pregnant and lactating women according to the national protocol for community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM).

The monthly unconditional cash grant (USD 84, or 80% of the minimum expenditure basket) was added to the programme in January 2020 to address household food insecurity. The grant was provided to families of children who originally suffered from severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and who had completed their treatment for both SAM and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM).

Figure 1 outlines the practical steps followed during programme implementation. Once successfully discharged from the CMAM programme, the child’s family was eligible to receive four rounds of cash grants over four consecutive months. These eligible households were enrolled onto the list of beneficiaries once the programme staff had confirmed that they were not entitled to any other cash assistance through other programmes.2 The list of beneficiaries was then communicated monthly to a “financial service provider” contracted by Save the Children, who notified beneficiaries of the five days of the month when households would be able to pick up their cash at a specific distribution point.

Enrolment of beneficiaries therefore followed a “rolling” system, in which beneficiaries were enrolled on an ongoing basis as children were discharged from the CMAM programme. For practical purposes, households were assigned to a cohort of beneficiaries. A total of 14 cohorts were formed during programme implementation. All the beneficiaries of a particular cohort collected their cash disbursement during the same period for each of the four rounds of cash disbursement. A “post-distribution monitoring” (PDM) exercise (data collection, including household surveys; detailed below) was conducted after each cash round (PDM1–PDM4) for all beneficiaries.

By the end of August 2021, a total of 1,669 families of children with severe wasting had been enrolled. Of these families, 1,011 had received four rounds of cash and 210, 320 and 128 families had received three, two or one round(s), respectively.

Figure 1: Linking households to the cash transfer programme upon a child’s discharge from the CMAM programme

CHV: Community Health Volunteer

CMAM: Community-Based Management of Acute Malnutrition

MAM: Moderate Acute Malnutrition

MUAC: Mid-Upper Arm Circumference

OTP: Outpatient Treatment Programme

SAM: Severe Acute Malnutrition

TFC: Therapeutic Feeding Centre

W/HZ: Weight-for-Height Z-Score

Methods used to conduct the performance review

The outcomes that resulted from adding a cash component to the nutrition programme were estimated by comparing data from before (baseline) and after the cash component was added within the CMAM programme (at PDM1–PDM4).

Baseline data were collected through a cross-sectional assessment conducted through a sample of 301 families of children suffering from SAM in the three districts where the programme would be implemented. A PDM was conducted after each round of cash distribution. For analysis, data from all cohorts were summed up for each PDM round, e.g. data collected after the first distribution were analysed together for all households, although households would have been enrolled in different cohorts. Data collection at baseline and all PDMs collected the same indicators detailed below, using a household-level structured questionnaire for all beneficiaries.

Household-level outcomes

Outcomes at the household level consisted of looking at how the cash disbursement was utilised and whether there were changes in coping strategies and food consumption scores (FCSs). The following three indicators were considered as part of the household questionnaires at each PDM.

Cash utilisation details were obtained based on a one-month recall period, to be consistent with monthly cash distributions.

The FCS is an index that aggregates household-level data on the diversity and frequency of food groups consumed over the previous seven days, which are then weighted according to the relative nutritional value of the consumed food groups (WFP, 2008). Based on this score, a household’s food consumption can be further classified into one of three categories: “poor” (0–21), “borderline” (21.5–35) and “acceptable” (>35).

The Reduced Coping Strategies Index (rCSI) is an indicator used to compare the hardship faced by households due to shortage of food. The index measures the frequency and severity of food consumption behaviours households have to engage in due to food shortages over the seven days prior to the survey (WFP, 2019). The maximum raw score for the rCSI is 56. Data were categorised into “low”, “moderate” or “high” levels of coping strategy. Four preselected coping strategies that households used over the seven days prior to conducting the PDM surveys are detailed in Box 1.

Box 1. The four types of coping strategy

Food insecure households typically employ any of four types of consumption coping strategy:

1. Households may change their diet, e.g. they may switch from preferred foods to cheaper, less preferred substitutes

2. Households can attempt to increase their food supplies using short-term strategies that are not sustainable over a long period, such as borrowing or purchasing on credit. More extreme examples are begging or consuming wild foods, or stocks of seeds

3. Households can try to reduce the number of people they have to feed by sending some of them elsewhere. This could involve sending children to a neighbour’s house when they are eating, or more complex medium-term migration strategies

4. Households can attempt to manage the shortfall by rationing the food available to the household, for example by cutting portion sizes or reducing the number of meals; favouring certain household members over other members; skipping whole days without eating; etc.

Individual-level outcomes

Individual dietary diversity information was obtained from the PDM surveys, which included a survey of caregivers to collect the eight food groups their child aged 6–23 months had consumed over the previous 24 hours. The minimum dietary diversity score was calculated as the proportion of children who had consumed foods from four food groups or more during the recall period. Although they received ready-to-use foods during their treatment, all children included in the analysis were no longer under treatment during data collection, neither at baseline nor at endline. Ready-to-use foods did not therefore compose a food category.

Achievements

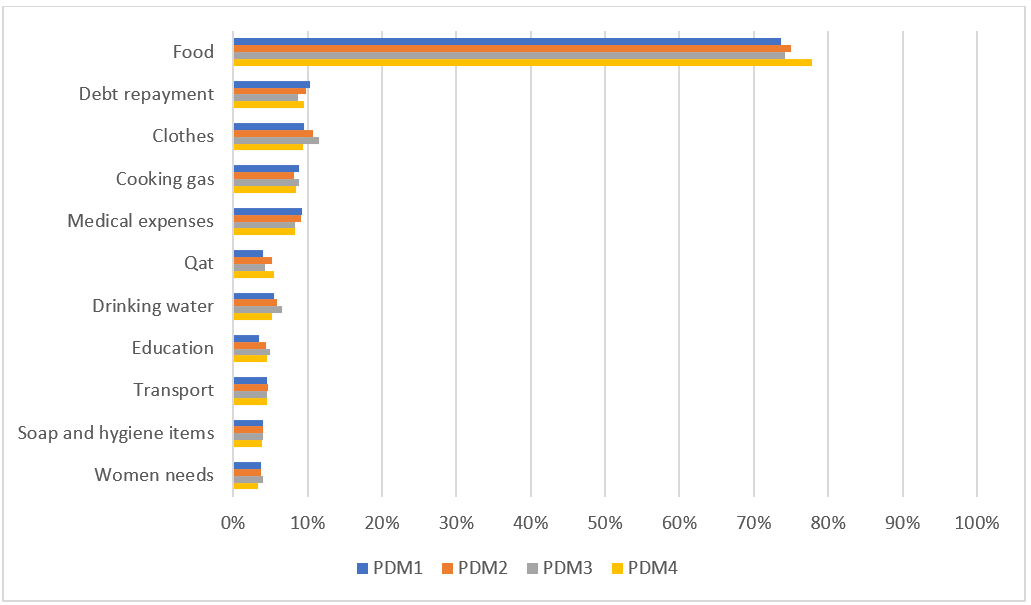

Utilisation of cash assistance

Analysis of the data showed that over 70% of the cash received by beneficiary households was used to buy food and almost another 10% was spent on cooking gas, followed by covering medical expenses (9%) and repaying debts (10%). The findings were consistent across all PDMs (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Utilisation of cash assistance

Household Food Consumption Scores

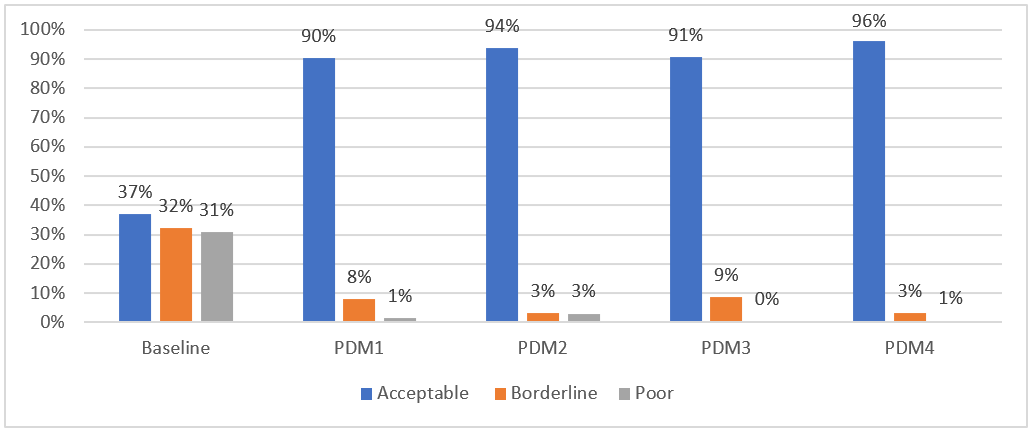

The baseline assessment showed that 63% of households with a child who had recovered from the CMAM treatment programme had either “poor” (31%) or “borderline” (32%) FCSs and were therefore unable to meet their nutritional requirements.

Between baseline and all subsequent PDM assessments, 60% of the families improved their FCSs from a “borderline/poor” to an “acceptable” level of food consumption, with 96% of families having acceptable FCS at PDM4 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: FCSs

Household coping strategies

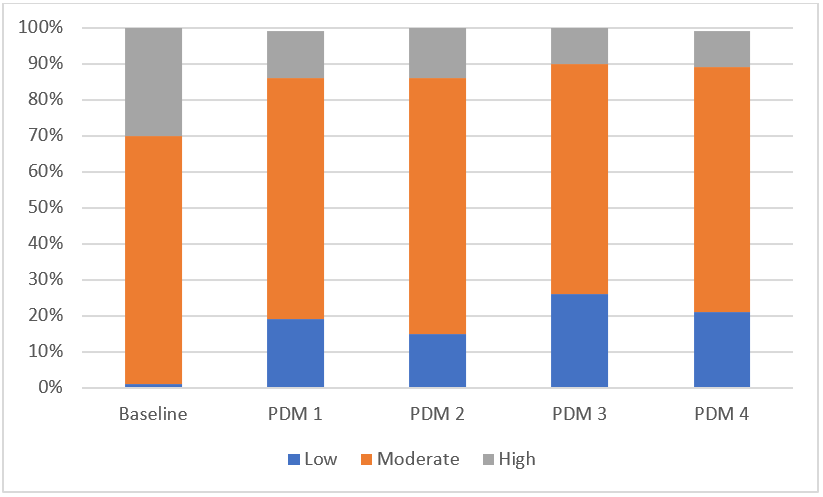

At baseline, 30% of families had a high rCSI score, indicating high reliance on negative coping strategies for food access. At subsequent PDMs, that level ranged between 10% and 14%. Similarly, the prevalence of families who had a low reliance on coping strategies increased with the implementation of the programme. The programme resulted in a reduction in the number of households relying highly on negative coping strategies (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Household Reduced Coping Strategies Index scores

Child feeding practices

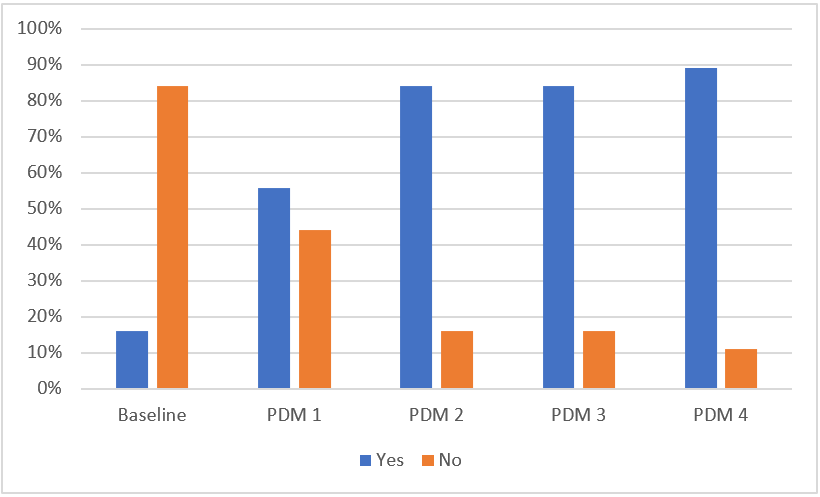

At baseline, analysis of data showed that only 16% of children aged 5–23 months were meeting the minimum dietary diversity score (≥4 food groups). After each round of cash assistance (PDM1–PDM4), dietary diversity scores showed meaningful improvement, with almost nine out of 10 children consuming food from at least four food groups after the fourth round of distribution (Figure 5). This suggests that cash assistance, coupled with caregiver sensitisation, contributed to improved household food consumption, as well as to children’s dietary diversity.

Figure 5: Dietary diversity scores in children aged 6–23 months

Key learnings

Programmatic arrangements

The four rounds of cash distribution aimed to strengthen financial security for families whose children were discharged “recovered” from the CMAM programme. A certain number of programmatic arrangements were made to ensure families would receive that financial support and use it for the most vulnerable members of the household. For instance, to ensure female caregivers would be able to collect the monthly grants (in a culture where women might not have the rights or the paperwork to do so), the financial service providers in charge of distributing the grants were instructed to accept a “recognition of ID” delivered to them by the community health volunteers (CHVs). Another arrangement was to give several alternative days (five) for household members to collect their grant from the financial service provider.

Programme treatment outcomes

The CMAM programmes showed improved performance indicators (the recovery rate increased, non-responder rate decreased and the defaulter rate decreased steeply) during the time the cash assistance component was added. All caregivers of children with severe wasting who were not receiving cash/food assistance from other organisations were informed of their potential eligibility for cash assistance if their children recovered during treatment. This may have acted as an incentive and motivated households to follow the advice given around childcare practices and supported regular treatment attendance. However, it is important to note that the impact of cash assistance on regular treatment attendance could not be statistically established due to other potential confounding factors, such as the maturity of the programme, improved mobilisation over the longer project duration and improved availability of commodities and services at the facility level.

Improvement in Food consumption

Programme data showed that families spent most of the cash they received on food and cooking gas. This resulted in the observation that the cash assistance led to meaningful improvements in household food consumption, as well as a greater diversity of children’s diets and reduced use of negative coping strategies.

Conclusion

This work makes an important contribution to the limited evidence base on cash assistance programmes. It demonstrates positive associations with food consumption, which in turn could potentially lead to improved nutrition outcomes. Specifically, findings showed that providing families with cash may have helped increase their expenditure on food and improved dietary diversity among children under the age of five. Cash distribution upon graduation from wasting treatment may also have promoted greater adherence to treatment programmes by children and their caregivers, with positive impacts on treatment performance indicators. We therefore believe that cash assistance should be scaled up to expand coverage to all food insecure families with children under the age of five, in all locations that are classified as IPC3 or worse in all the districts of the Hajjah governorate.

As next steps, the project team will provide more dedicated technical support to ensure appropriate collection of relapse information during admission, as well as to improve data recording and reporting from health facilities. Save the Children, in collaboration with the Nutrition Cluster, will continue to advocate for the approval of relapse research from the authorities to explore whether cash assistance can contribute to reductions in relapse rates. Save the Children will also consider sharing these learnings with the Food Security and Agriculture Cluster (FSAC) and Nutrition Cluster partners to sensitise and advocate scaling up cash for nutrition programming in Yemen and to engage more partners in support of the government’s efforts to tackle food and nutrition insecurity.

For more information, please contact Tammam Ahmed at tammam.ahmed@savethechildren.org.

References

ACF (2018) Nutrition and Retrospective Mortality Survey – Highlands and Lowlands Livelihood Zones of Hajjah Governorate.

https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/yemen/document/smart-survey-hajjah-march-2018.

IPC (2018) Yemen: Situation Overview and Key Drivers. IPC Acute Food Security Analysis, December 2018–January 2019. https://reliefweb.int/report/yemen/yemen-ipc-acute-food-insecurity-analysis-december-2018-january-2019.

WFP (2008) Food Consumption Analysis: Calculation and Use of the Food Consumption Score in Food Security Analysis.

https://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/manual_guide_proced/wfp197216.pdf

WFP (2019) Reduced Coping Strategies Index. https://resources.vam.wfp.org/data-analysis/quantitative/food-security/reduced-coping-strategies-index.

1 The food consumption score (FCS) is a composite score based on the dietary diversity, food frequency and relative nutritional importance of different food groups. This is a proxy indicator to measure caloric intake and diet quality at household level, giving an indication of the food security status of the household if combined with other household access indicators (ACF, 2018).

2 Only 55 children’s families fell into that category during programme implementation .