A digital messaging intervention and remote data collection to support ECD & nutrition: Telangana, India

Reetabrata Roy is Programme Director at Sangath, India

Khyati Tiwari is a Nutrition Specialist at the UNICEF office of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Karnataka, India

Gitanjali Lall is a Research Coordinator at Sangath, India

K Sharath Chandrika is a former Research Associate at Sangath, India

Deepak Jangra is a Data Manager at Sangath, India

Narasimha Rao Gaddamanugu is a Consultant for Infant, Young Child Nutrition and Early Child Development at the UNICEF office of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Karnataka, India

Gauri Divan is Director of the Child Development Group at Sangath, India

Key messages:

- This article explores the development of a digital messaging intervention and methodologies used to collect data remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic - in Telangana, India - which targeted message recall, early child development and infant and young child feeding practices.

- The digital messaging intervention leveraged an existing opportunity in Telangana, one of the states with the highest penetration of mobile phones and internet usage, including ownership of phones among women, which ensured that messages delivered through the intervention achieved significant reach among beneficiaries.

- While digital messaging is a promising model to reach women with messages, it cannot replace the critical interpersonal communication offered by frontline workers. Both models are therefore complementary.

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic and its associated lockdowns impacted the health, nutrition, and learning of children in multiple ways (Yoshikawa et al., 2020). These included impacts of protracted lockdowns and family unit disruptions on immediate socioemotional development outcomes, including adverse effects on children due to increased caregiver stress; the trickle down economic implications on household food availability; direct infection from the virus itself, both in the immediate and longer-term; and the implications of curtailing progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2020). Restrictions imposed during the pandemic reduced access to services, especially for vulnerable populations, which had a knock-on effect on multi-sectoral initiatives and child health services - such as school feeding programmes and child immunization (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2020).

Despite these disruptions, community workers - including Anganwadi Workers (AWW) in India - demonstrated both resilience and industry (Nanda et al., 2020), distributing food to families to support complementary feeding for young children and using technology to deliver relevant nutrition and health messages. The distribution of family level food allowance, or ‘ration’, was amongst the least disrupted child health services, with periods between lockdowns seeing moderate resumption in this service (Avula et al., 2022).

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, community level service delivery for components under POSHAN Abhiyaan (the National Nutrition Mission) were brought to a standstill in India. The Department of Women Development & Child Welfare (DWDCW), Government of Telangana & UNICEF conducted rapid online assessments to better understand service delivery gaps within the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) and National Health Mission. While improvement was reported in take-home food ration and growth monitoring, counselling services remained unavailable for over 90% of beneficiaries. In response to this unmet need and to complement POSHAN Maah (Nutrition month), in September 2020, a digital messaging intervention was developed for community dissemination. Sangath, a non-for-profit organisation, who led the development of this intervention, as part of the Aalana Palana intervention (Box 1) that was initiated in the state before COVID-19.

Box 1: The Aalana Palana intervention

The Aalana Palana intervention is a part of ASPIRE - A Scalable Programme IncorpoRating Early child development interventions - a collaboration between Sangath, DWDCW and UNICEF. Aalana Palana, which is delivered by AWWs at the community level, aims to promote nurturing care during the first 1000 days by integrating early child development (ECD) & nutrition messages through the use of videos Aalana Palana in Telugu - implies a caring and nurturing environment provided by caregivers to their children. It promotes an inclusive environment for adequate nutrition, responsive and sensitive caregiving, including opportunities for learning and access to quality health services. Aalana Palana draws from the internationally promoted Nurturing Care Framework on early child development that provides healthcare providers and caregivers guidance on giving children the best start in their lives.

This article aims at sharing the experiences and learnings from the development of this digital messaging intervention and methodologies used to collect data remotely during the pandemic, targeting message recall, ECD and Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) practices.

Methods

Development of the digital messaging intervention

The rationale of developing this digital intervention using multimedia formats (video, audio and text) was based on existing mobile and internet access in Telangana. National Family Health Survey 5 (2019-21) data shows that over 75% households in the state have at least one mobile phone, with over 50% women in rural and 75% in urban Telangana having ownership. Internet availability is at 42% across the state.

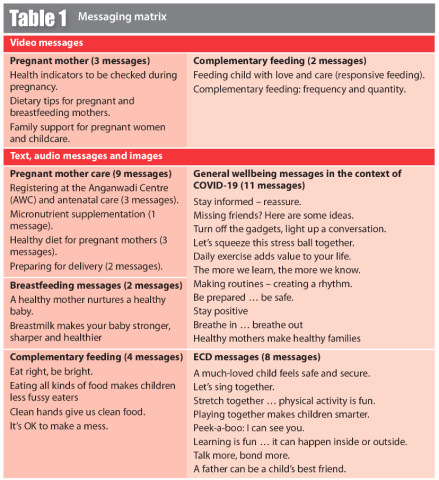

To develop key messages on ECD and nutrition the Aalana Palana team reviewed relevant literature, including UNICEF and WHO guidance for supporting responsive parenting strategies during the pandemic (Parenting for Lifelong Health, n.d.; UNICEF, n.d.). The team produced a messaging matrix to guide development of key messages (Table 1).

Since shorter videos often receive more views (Ferreira et al, 2021), the video and audio messages were kept brief at between 60-120 seconds in duration. All messages included information to address challenges regarding access to resources, limited mobility outside the home and associated stress in both children and caregivers. The appropriateness of the messages was checked with AWWs who had considerable experience of working in the community, especially during the pandemic.

The final set of messages across the media mix was shared with AWWs, and two virtual training sessions were carried out to optimise circulation of the content across multiple platforms. Messages were made available on the DWDCW website and on a state-hosted YouTube channel.1 Social media channels (Facebook and Instagram) were also used. AWWs forwarded the messages to WhatsApp groups for pregnant and breastfeeding women and their family members. Text messages reiterating key points were sent by centralised servers managed by DWDCW to registered mothers. In addition, AWWs further discussed the messages during their limited in-person interaction with women during the distribution of the take-home food ration.

For families who did not have internet or smartphone access, and to supplement social media messaging, other media included in this intervention were direct phone calls to families through a government-operated line and communication with AWWs through a satellite television channel operated by the DWDCW, known as T-SAT.

Remote data collection on coverage and recall of the digital messaging intervention

A message recall survey was conducted with 5377 randomly selected pregnant women & mothers of children under 2 years of age in 16 districts of Telangana. These women were contacted through telephone calls and WhatsApp messages. They were asked questions about whether they had received any digital messages from the health system, what the format and content of the messages was, whether there were any further queries, if there were, whom they reached out to for an answer and, finally, whom they shared the messages with. Coverage of the digital messaging intervention was also assessed via tracking the number of WhatsApp groups created between frontline workers, including AWWs and families in their catchment area on which these messages were circulated widely. Impressions on social media including views, comments, shares on social media were tracked to estimate coverage on these platforms.

Remote data collection on ECD and IYCF practices during the COVID-19 pandemic

242 pregnant women and mothers with children between 6-36 months of age residing in the catchment area of 30 Anganwadi Centres (AWC) were randomly selected and approached for telephonic interviews.

Data was collected using a semi-structured questionnaire, which consisted of adapted versions of standardised questionnaires as well as questions based on literature review (Box 2). Owing to the telephonic mode of administration, certain items such as measuring the quantity of food that the child ate using a standard bowl, had to be omitted. Questionnaires had to be reduced in order to minimise the administration time of the interview. Mock administrations were conducted within the team in order to test the final questionnaire.

Box 2: Survey components/topics

- Household financial security, including information on loss of employment

- IYCF practices, using the WHO Complementary Feeding Questionnaire (adapted) (WHO, 2021)

- Quality and extent of stimulation available to a child in the home environment (both interaction and physical environment), adapted from the Family Care Indicators (Kariger et al, 2012)

- Healthcare service provision through AWC for pregnant women and children, including measurement of height and weight, food supplementation and deworming

- Measurement of exposure to violence or neglect at home

Calls were made by a research assistant from Sangath who had previous interactions with these families during a baseline conducted in the ASPIRE program (results of the baseline are not presented in this article). This rapport with the participants created during baseline was used to increase the chances of participation and cooperation in the sub study. The research assistant was trained on administering the questionnaires and obtaining, and recording, consent over the phone. An excel database was maintained, which contained demographic details as well as a record of call attempts.

Given the sensitive nature of certain questions, specifically those pertaining to violence towards the child and mother, information regarding helplines was provided and a follow up was completed to check if the family had received any required support.

Since the questionnaire took between 20 - 30 minutes to administer, flexibility was offered regarding time of the day and number of sessions across which the questionnaire could be delivered.

Ethical review and quality control

Participant consent was recorded over the phone after obtaining permission from the respondent. Prior to obtaining consent, an information sheet was read aloud and caregivers were encouraged to ask questions.

The study was cleared by the Sangath Institutional Review Board.

A group counselling session in Telangana. India © Sangath

Results

Digital messaging intervention

During POSHAN Maah and the extended digital counselling rounds conducted between September and December 2020, 27,757 WhatsApp Groups were created by AWWs with their beneficiaries. This represented 78% of Anganwadi centres (AWCs) in the state. The remaining AWWs could not connect to beneficiaries in their catchment area due to poor internet connectivity. 227,000 (94%) pregnant and lactating women and 423,000 (65%) parents and other family members of young children (7-72 months) were reached through these groups.

WhatsApp messages reached more than 60% of all registered women beneficiaries in the state. Besides these direct beneficiaries, 100,000 (60%) Village Panchayats members, municipality post-holders, and women collectives received these messages. Social media reach was estimated at 1,500,000 people between September-December 2020.

Message recall survey

Across 16 districts, an average of 84% of women recalled receiving messages in the week preceding the survey via WhatsApp. Results were largely comparable across districts, ranging between 81-89% in 13 out of the 16 districts.

Among women who were able to recall messages, 97% were able to remember pregnancy-care related messages followed by 93% for breastfeeding, and 77% for complementary feeding messages. 97% of women reported receiving these messages on WhatsApp groups created by their AWWs and 88% of women reported sharing messages among their peers and discussing it further with AWWs and family members.

Sub-study on ECD and IYCF during COVID-19

Of the 242 caregivers approached for the sub-study, 208 responded and consented to participate. 31 caregivers were not contactable, and 3 children were deceased.

The results of the sub-study indicated that 51% mothers reported receiving support from family members for feeding their children during the pandemic. Father’s participation in child feeding was reported by 18% mothers. Additionally, 71% mothers reported receiving food from AWCs both before and during the COVID-19 lockdown. Only 43% were able to get their child vaccinated and 39% were able to get their child’s height and weight measured both before and during the COVID-19 lockdown.

For parent-child interactions, 34-42% of caregivers reported playing, reading, singing etc. with their child during the pandemic, yet hadn’t engaged in such activities before the onset of the pandemic.

Most children (95%) received grains & roots in their diet, followed by other fruits and vegetables (84%), dairy products (75%), Vitamin-A-rich foods (72%), and Eggs (61%) (figure 1). A quarter of children received legumes & nuts (26%). Flesh foods, including bird or animal meat & products made from these items, were consumed by 17% of children. Almost two thirds (63%) of children received the WHO recommended minimum acceptable diet in the 24 hours preceding the survey, 73.5% received four or more food groups, and 92% received the recommended number of meals.

Lessons learned

This digital messaging intervention built on the opportunity that Telangana provides, by being one of the states with the highest penetration of mobile phones and internet, including ownership of phones among women. This ensured that key messages delivered through this intervention across multiple themes achieved significant reach among beneficiaries even during the pandemic.

Key learnings from the development of the digital messaging intervention as compared to in-person counselling centred around making the messages sufficient in themselves, such that they would be effective even in the absence of a facilitator going through them with the families. This included significantly simplifying language, using colloquial terms and elaborating concepts. For audio recordings increased importance was given to voice modulation and using a conversational tone, so as to make the messages appealing enough for caregivers.

A key challenge remained, however, of customising messages to cater to the individual needs of families. To address this, customised tele-calling was later initiated for women addressing specific concerns; however, this was possible only in a smaller geography. In addition, the digital messaging intervention served as a tool for the AWWs to engage in discussions with community members ensuring continuity of counselling services, uniformity in messaging and minimising information loss.

The messages developed for digital delivery have been integrated into various government schemes, including the wider Aalana Palana video intervention. Government frontline functionaries can facilitate delivering the digital content through use of different social media platforms especially creatively using WhatsApp groups. It is important to align and integrate messages used on different platforms and schemes (like Aalana Palana) to maintain consistency and continuity.

In addition to the findings from the two cross sectional surveys presented above, later interactions with beneficiaries after the easing of the pandemic related restrictions showed an encouragingly high rate of recall of key messages. During these exchanges with ICDS functionaries at community-based events and home visits by AWWs it was observed that women who were exposed to the digital messaging intervention were able to recall messages and had adopted certain behaviours promoted during its implementation. These included behaviours on pregnancy care and hygiene, such as maternal nutrition supplementation, deworming, managing stress during the pandemic, and hand washing during food preparation, before and after feeding children. Messages on fathers’ and other care providers’ role to support mothers in child care and feeding also were also remembered.

A major challenge of the telephone surveys was the fatigue encountered by respondents, which at times impacted the quality of their responses. Another consequence of this was the inability to complete all questionnaire sections in a single session, requiring on occasion, multiple attempts to contact caregivers. The duration of the phone calls was further increased when families, who were already in a state of stress due to the pandemic, discussed their personal struggles, thereby deviating from the actual interview. Therefore, method of telephonic survey requires careful planning that considers length of the tool, time and number of contacts, respondent’s situation.

Conclusion

Our experience demonstrates that government frontline functionaries can effectively use a mix of high-dose universal digital messaging in combination with targeting specific individual needs through one-on-one counselling to maintain continuity and consistency of messages and behaviours even during pandemic situation. While digital messaging is a promising model to reach women with messages, it cannot replace the critical interpersonal communication with frontline workers like AWWs. Both models are complementary. A community-based mechanism for triaging pregnant women, mothers and young children into high-risk categories and providing them with additional home visits or creating referral pathways for specialised consultations is also required.

Digital platforms can also support incorporating methods for collecting data through chatbots or e-surveys along with coverage of digital messaging, to ensure systematic collection of process indicators and data related to improvement in knowledge levels.

The lessons learnt from Aalana Palana during this unprecedented pandemic and associated lockdowns can be expanded to support young children and their caregivers in future disasters. Such disaster preparedness will be essential to ensure that services to the most vulnerable of our populations are minimally disrupted in the future.

For more information, please contact Reetabrata Roy at r.roy@sangath.in

References

Avula R, Nguyen PH, Ashok S et al (2022) Disruptions, restorations and adaptations to health and nutrition service delivery in multiple states across India over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: An observational study. PLOS ONE, 17, 7, e0269674. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269674

Ferreira M, Lopes B, Granado A et al (2021) Audio-visual tools in science communication: The video abstract in ecology and environmental sciences. Frontiers in Communication, 6, 1. www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2021.596248/full

Kariger P, Frongillo E, Engle P et al (2012) Indicators of family care for development for use in multicountry surveys. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 30, 4, 472-486. https://doi.org/10.3329/jhpn.v30i4.13417

Nanda P, Lewis T, Das P et al (2020) From the frontlines to centre stage: Resilience of frontline health workers in the context of COVID-19. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 28, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2020.1837413

Parenting for Lifelong Health (n.d.) Covid-19 Parenting. www.covid19parenting.com/#/home

Pérez-Escamilla R, Cunningham K & Moran VH (2020) COVID-19 and maternal and child food and nutrition insecurity: A complex syndemic. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 16, 3, e13036. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13036

UNICEF (n.d.) Coronavirus (COVID-19) Parenting Tips. UNICEF. www.unicef.org/coronavirus/covid-19-parenting-tips

United Nations (2020) Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Children. https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-impact-covid-19-children

WHO (2021) Indicators for Assessing Infant and young Child Feeding Practices: Definitions and Measurement Methods. www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240018389

Yoshikawa H, Wuermli AJ, Britto PR et al (2020) Effects of the global COVID-19 pandemic on early childhood development: Short- and long-term risks and mitigating program and policy actions. The Journal of Pediatrics, 223, 188-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.020