A descriptive analysis of gaps in nutrition services across multiple countries

This is a summary of the following paper: Ramadan M, Muthee T, Okara L et al. (2023) Existing gaps and missed opportunities in delivering quality nutrition services in primary healthcare: A descriptive analysis of patient experience and provider competence in 11 low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Open, 13, 2, e064819. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36854587/

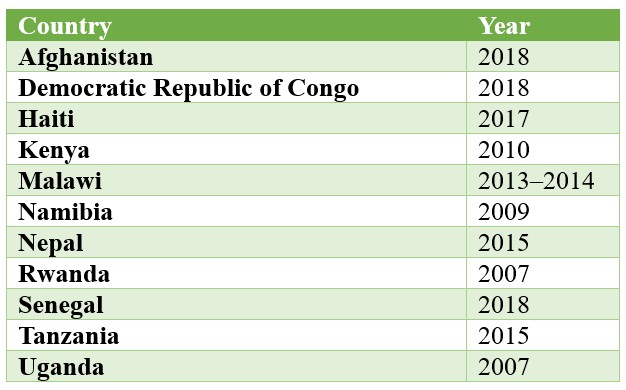

This cross-sectional study analysed standardised, publicly available service provision assessments – comprehensive surveys that collect data from primary healthcare facilities – across 11 countries (Table 1). The secondary data analysis aimed to assess the competence of primary healthcare providers in delivering essential and preventative nutrition services and patients’ experiences in receiving the recommended components of care. Patient experience was assessed through self-reported nutrition service awareness, while provider competence was assessed via direct observation during antenatal care and sick child visits.

To perform the analysis, all outcome variables associated with both patient experience and provider competence were coded as either 1 (available) or 0 (not available). These binary variables were then used to generate facility-level averages for analysis. Data were obtained for 18,644 antenatal care and 23,262 sick child visits across 8,458 facilities.

Table 1: Service provision assessments included in the cross-sectional study

All but one country (Democratic Republic of Congo) reported patient experience scores below 50% and provider competence was below 50% in every country. Patient experiences with child nutrition services were found to be significantly poorer compared to maternal services. Across all countries, less than 42% of clients reported that their child’s weight and growth were discussed with them. In 10 of the 11 countries, only 40% of clients received appropriate fluid intake or breastfeeding counselling and less than 40% received solid food counselling during illness. The Democratic Republic of Congo was an exception, as 99% of clients reported being advised on both fluids and solids.

Although the patient experiences were generally poor across the board, most providers (>72%) explained how to take iron and folic acid at an antenatal care visit. Despite this, knowledge exchange regarding iron side effects was poor (<31%) across all countries, highlighting a lack of depth in nutrition consultation. In addition, in all countries with available data, less than 20% of observed providers advised on early breastfeeding practices. A full breakdown of results for separate indicators can be found in the original paper.

The authors found compelling evidence of a lack of depth in providers’ assessment of the nutritional status of expectant mothers and children.”

A limitation of the study is that data were taken from different time points across different countries; therefore, although this provides an overall picture, it is difficult to compare the findings between countries as indicators change over time. Patient experience was also a self-reported measure, which lends itself to reporting bias, although this method has provided a large sample size to draw from, which is a positive.

Another important consideration is that the analysis was only conducted for primary facilities (n=6,248, 76% of the sample). This means that these results are only valid for community-based nutrition services. Most data were collected from rural settings.

Although measuring quality nutrition service data in the primary healthcare system remains challenging, this evidence highlights that services were lacking in the 11 assessed countries. There are significant opportunities for improvement.