Father-to-father support groups in northern Nigeria: An emergency response initiative

Lisez cet article en français ici

Solomon Atuman is a Nutrition Coordinator at FHI 360

Onesmus Langat is a Monitoring and Evaluation Coordinator at FHI 360

Alessandro Iellamo is a Senior Emergency Nutrition Adviser at FHI 360

Simon Idoko is a Senior Technical Officer, Nutrition at FHI 360

What we know: Male caregiver decisions directly influence female caregivers’ abilities to utilise the knowledge gained through mother-to-mother support groups. Engaging with fathers alongside mothers can increase programme effectiveness.

What this adds: After three years of implementing a community-led father-to-father support group (FTFSG) programme, a greater proportion of intervention households reported adequate infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices than those from comparison households. Challenges included strong cultural norms, competing priorities of fathers as main providers, and limited sustainability of the approach beyond the direct programme phase.

Background

Nigeria is home to the second-highest number of stunted children in the world (15 million), and only 20% of the 2 million children who suffer from severe wasting receive treatment (UNICEF, 2023). Almost 2 million people have been displaced in Nigeria’s north-eastern states, 81% of whom reside in the state of Borno.

Living conditions in the state restrict appropriate IYCF practices (NPC Nigeria and ICF, 2019). Only 44% of children were put to the breast within one hour of birth, 45% of children were exclusively breastfed at six months, and 55% of children continued breastfeeding at 12–23 months (Nutrition Cluster and UNICEF, 2022). Complementary feeding practices fare worse, with less than 20% of children aged 6–23 months achieving a minimum acceptable diet. Provision of services to prevent childhood malnutrition is also low, with 32% of children receiving vitamin A supplementation, 16% being dewormed, and only 6% receiving micronutrient powders.

Since 2017, FHI 360 has implemented four iterations of an integrated humanitarian assistance project in three local government areas of Borno state – Bama (Bama town and Banki), Ngala, and Mobbar (Damasak). This project aimed to improve the nutritional status of children under five years and of pregnant and lactating women in both internally displaced people camps and host communities. To address cultural determinants of IYCF practices, our evidence-based social and behaviour change communication approach (Lamstein, 2019), including community support groups, was used to improve IYCF practices.

Community support groups provide spaces for conversations around breastfeeding, supporting decision making and ensuring that women have the best breastfeeding experiences possible in their communities. Mother-to-mother support groups have been running since 2017. However, a 2018 knowledge, attitudes, and practices survey (FHI 360, 2018) found that decisions made by male caregivers directly influence female caregivers’ abilities to utilise the knowledge gained through these support groups. In response, the FTFSG initiative was designed by FHI 360 to involve fathers in childcare and enhance the adoption of improved IYCF practices.

Father-to-father support groups overview

Funding was secured from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance to initiate the FTFSG initiative in April 2019. A total of 484 FTFSGs have been established to date. At the end of 2022, a total of 2,412 FTFSG sessions had been held - reaching 30,917 men.

Each support group contains 8-15 men and is led by a facilitator who provides counselling, supporting group members to adopt best practices. The facilitator is a male volunteer selected in collaboration with community leaders using set criteria. Relevant IYCF, reporting, and counselling training is provided to facilitators by FHI 360 technical staff. Within each support group, one particularly active member is selected as the ‘lead father’ to assist the facilitator in coordinating the group and encouraging attendance. Social and behaviour change communication strategies - including community mobilisation, social marketing, interpersonal communication, and use of education materials - are used to promote positive changes among the groups.

Face-to-face meetings are held monthly and last 30-60 minutes, depending on the interest of the group members in the particular topic. One topic is selected and discussed per month, with all 12 topics covered by the time the group graduates after one year. New members are enrolled for the following one-year period, thereby enabling more men to serve as mentors and to disseminate IYCF knowledge within their community.

UNICEF IYCF counselling cards were adopted by the Nigerian government for use at community level, providing visual tools that facilitate conversations with support groups (SPRING and USAID, 2012). Counselling topics included general hygiene, early initiation of breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding until six months, complementary feeding practices, and maternal nutrition - especially during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Men are encouraged to support their wives and children within their roles as fathers, including encouraging them to carry out common household chores such as cleaning, helping to feed the child, and engaging with healthcare (e.g. taking a child to the health facility or for immunisation, accompanying their wife to health centres or antenatal services, etc.).

A community dialogue session is first conducted to ensure community engagement. After an initial introduction, community members can suggest how they want to structure the group, including deciding on the timings and venue of the meetings. Recruitment into each support group is voluntary and based on locality, with groups being open to all men who are heads of households, particularly fathers.

Monitoring data, including the number of sessions held and individuals reached, are routinely collected by the facilitator and technical staff using support group registers and summary forms.

Impact Assessment

In July 2022, after three years of implementation, we conducted an evaluation to assess the impact that FTFSGs had on knowledge, attitudes, practices, and, to some extent, nutrition outcomes. Data were collected from primary caregivers of children aged under five years using a quantitative household survey and focus group discussions (FGDs). In households with more than one child under five, the survey focussed specifically on the youngest child in the household.

We employed a quasi-experimental1 impact assessment technique to compare results between an intervention group (households of FTFSG members who had completed the curriculum) and a comparison group (non-member households). There were no baseline data available to compare changes over time, nor to assess the comparability of intervention and comparison groups prior to implementation of the FTFSGs.

Settlements, and households within those settlements, were randomly selected through a multi-stage sampling technique based on probability proportional to population size. Only households in which both mothers/primary caregivers of children aged 0–59 months and their fathers were 18 years or older were considered for inclusion. Intervention households were selected from membership lists collated across all locations and comparison households from lists of non-participating households generated by community facilitators.

In total, 168 groups had completed the curriculum and graduated: 56 in Banki, 56 in Bama, and 56 in Damasak. Dikwa was excluded from the study, as no groups could be safely visited. Finally, 264 respondents were selected: 136 in households from the intervention group and 136 from the comparison group.

Results

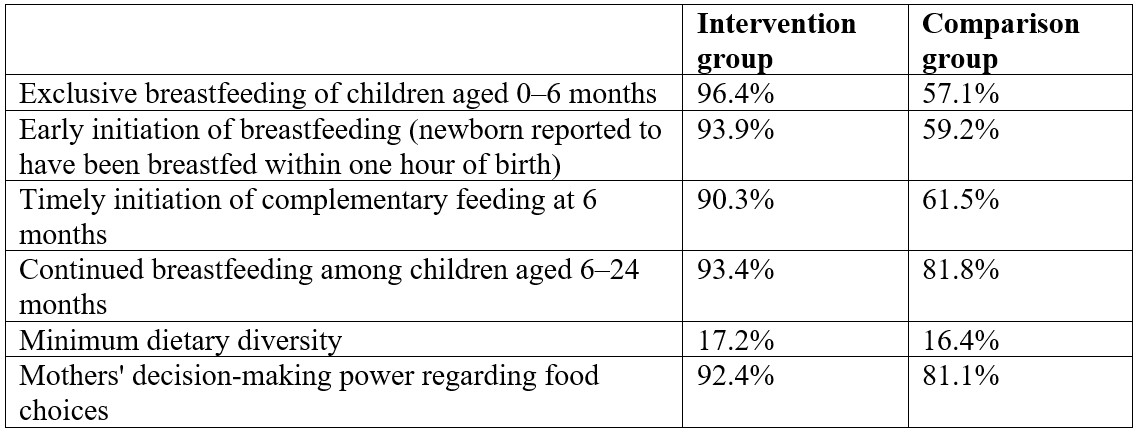

Results from the quantitative survey showed that, after three years of programme implementation, a greater proportion of respondents from intervention households reported adequate IYCF practices than those from comparison households (Table 1). Adequate breastfeeding behaviours were reported by more than nine out of ten caregivers of children under five years of age in the intervention group, compared to between five and eight in the comparison group, which is already a higher prevalence than local and national levels (see the Challenges section). Minimum dietary diversity was overall low, with limited difference between the intervention and comparison groups. This reflects the similar constraints faced by both groups in terms of access to diverse nutritious foods and financial resources, which cannot be addressed by behaviour change interventions alone.

Most mothers participating in the FGDs reported that their husband's participation in the FTFSG had improved IYCF practices in their households.

"Since our husbands joined FTFSGs, we have learnt many things through them such as environmental hygiene, antenatal care visit, hospital delivery, using locally available foods to prepare different varieties of foods, taking a sick child to the hospital, caring for the sick child, the importance of early initiation, exclusive breastfeeding, and complementary feeding" - Mother, FGD participant.

Most women in both intervention and comparison households reported having decision-making power over food choices for family feeding. This is generally considered a women's domain, with men viewing themselves as providers and women as responsible for feeding the family. During FGD sessions, men from the intervention group reported contributing to providing safe drinking water and supporting household hygiene practices through clearing grass around the house, ensuring a clean environment, and regular handwashing after using the toilet and before eating.

"Joining FTFSG meetings has opened our eyes as we learnt many things and can let go of some norms and beliefs that contribute greatly to malnutrition. Now our children are doing well through effective IYCF practices, such as early initiation, exclusive breastfeeding, and combining different food groups to make a nutritious meal as we were taught" - FTFSG participant.

More caregivers in intervention households reported that they had heard of child spacing (79%) and that their husbands were in support of this (80%) than those in comparison households (57% and 57% respectively). Around 99% of respondents from intervention households reported referring the youngest child to the health facility the last time they were sick, compared to 88% of respondents from comparison households.

"As soon as we observe the children are unwell, we quickly refer to the hospital. No longer visiting the traditional healer or religious home and (we need) no money to go to the chemist" - FTFSG participant.

Success

Programme design: Careful design of the programme to respond to the needs of mothers in the community, including the social and behaviour change communication strategy monitoring system, contributed to its success and allowed adjustments to be made to programme delivery modalities. Support group facilitators comprised young, middle-aged, and older fathers with a good understanding of the sociocultural barriers experienced by other group members.

Utilising an older support group facilitator, who commanded great respect and held influence with community leaders, allowed for effective key message delivery. Sustained capacity building of the FTFSG facilitators also ensured that they could manage support group meetings and adapt messages to the local context.

Community participation: The programme was poorly perceived and not well accepted by communities at the start. However, continuous community engagement, sensitisation, and advocacy increased community acceptance and ownership over time. Awareness of local languages, norms, and health-seeking behaviours enabled positive contact with the community to support context-specific programme design and implementation.

Regular efforts were made to build good working relationships with community leaders to familiarise them with the FTFSG approach and gain their support. Fathers who were community leaders played dual roles through participation in FTFSGs and community dialogues, making it easier to encourage adoption of appropriate behaviours.

Programme monitoring: Implementation of a monitoring system allowed for ongoing identification of strengths and weaknesses in the FTFSG programme to support quality improvement. As well as tracking attendance, the system used standard IYCF tools to assess participant knowledge and behaviour change, and to evaluate the effectiveness of the support group facilitators. Regular feedback was provided to the facilitators and other stakeholders to identify areas for improvement and promote continuous learning.

Successes

Evaluation of impact: This assessment evaluates the impact of FTFSGs based on reported IYCF practices. Intervention groups may be more likely to report what they know they should be doing based on information provided during group meetings than comparison groups who have not participated. It is also possible that exposure to other interventions, such as mother-to-mother support groups, of which 46% and 21% of respondents from intervention and comparison households respectively were members, influenced the responses provided.

Strong gender and cultural norms: Gender norms dictate that fathers are responsible for providing for the household and this affected support group attendance in cases where sustaining livelihoods was prioritised. Similarly, while positive impacts have been documented for FTFSG members, some cultural norms do not support men’s involvement in household chores or in daily caregiving, limiting their adoption of key messages. Advocacy targeted at community leaders, along with sustained social and behaviour change communication strategies, were incorporated to address this.

Difficulties with programme implementation: A lack of comfortable locations for FTFSG meetings in the community made selecting appropriate venues a challenge. Some members had to host meetings in their own houses. Meeting schedules sometimes coincided with days designated for other activities - such as farming, markets, and food distribution. Liaising with group members flexibly was therefore required to ensure that feasible days were agreed upon.

The emergence of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic also affected programme implementation and regular meetings were suspended for two months. Once reinstated, activities were adapted to include COVID-19 prevention and mitigation measures with guidance from the nutrition sector.

Sustainability: Ensuring the sustainability of the FTFSG programme has been challenging. Maintaining sufficient resources and the involvement of trained facilitators may not be feasible over the longer term. Few meetings have been recorded after participants graduated from the programme, indicating a lack of sustained mentorship and key message dissemination that may limit future impact and scalability.

Insecurity: Security threats and population displacement disrupted some activities.

Conclusion

Findings from this evaluation indicate that fathers’ involvement in support group meetings has improved the uptake of recommended IYCF practices at household level, suggesting potential to contribute to reducing childhood malnutrition in vulnerable groups, such as those displaced by humanitarian crises. Other sectors could explore the use of FTFSGs to support adoption of other behaviours where gender and cultural norms influence acceptance within households.

FHI 360 plans to continue the approach in new projects being implemented, and to share these experiences and lessons learnt with other members of the Nutrition Cluster. However, expansion and sustainability of FTFSGs is critical to achieving optimal IYCF practices and more work is needed to understand how this may be achieved.

For more information, please contact Solomon Atuman at satuman@fhi360.org

References

Family Health International (2019) Borno State Health, WASH & Nutrition KAP Survey Report for the Integrated Humanitarian Assistance to North-East Nigeria Project (October 2018). reliefweb.int.

Lamstein S, Pérez-Escamilla R, Adeyemi S et al (2019) Impact of UNICEF’s Community Infant and Young Child Feeding (C-IYCF) Counselling Package on Priority IYCF Practices in Nigeria (P16-038-19). Current Developments in Nutrition. 3 (Supplement 1): P16-038-19.

Ministry of Health (2010) National Policy on Infant and Young Child Feeding in Nigeria. Abuja, Nigeria: Government of Nigeria.

National Population Commission (NPC) Nigeria and ICF (2019) Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF.

Nutrition Cluster and UNICEF (2022) North-East Nigeria nutrition & food security surveillance (NFSS), round 12 – August to September 2022, final report (December 2022). reliefweb.int.

OCHA (2023) Nigeria Humanitarian Response Plan 2023 (February 2023). reliefweb.int.

SPRING and USAID (2012) The Nigeria Community and Facility Infant and Young Child Feeding Package. spring-nutrition.org.

UNICEF (2023) Nutrition. UNICEF Nigeria. unicef.org.

1 In a quasi-experimental design, the randomisation is done after the intervention has taken place (a posteriori), rather than a priori, according to groups of people (communities in this case) rather than individuals.