Caregivers’ perceptions of children's diet and development in northern Laos

Sophie-Anne Sauvegrain Anthropologist at Nutriset, France

Didier Bertrand Independent Researcher in Cultural Psychology in Laos

Monique Chan-Huot Director of Innovation at Groupe Nutriset, France

Vanphanom Sychareun Public Health Professor at the University of Sciences and Health in Vientiane, Laos

Phonevilay Santisouk Senior Lecturer at the University of Sciences and Health in Vientiane, Laos

Vilamon Chanthaluesay Teaching Associate at the University of Sciences and Health in Vientiane, Laos

This study was funded by Nutriset Group, a developer and supplier of therapeutic solutions to the World Food Programme (WFP). It does not discuss the impact of products received by beneficiaries, nor does it promote any Nutriset products or commercial interests. Its social and anthropological approach to determine perceptions of child development aims to build on existing knowledge. The authors declare no conflict of interest in the publication of this article.

What we know: Food insecurity and malnutrition are widespread among ethnic minorities from northern Laos. In response, humanitarian assistance, in the form of specialised nutrition supplements, was provided to support this group.

What this adds: This study highlights the importance of natural food in both its symbolic and nutritional dimensions. The authors recommend adopting a comprehensive approach that includes anthropological considerations when setting up nutrition interventions and to define strategies that are adapted to individual contexts, cultures, and social relations.

Background and Introduction

This study was carried out in Luang Namtha Province in the mountainous region of northern Laos. Luang Namtha is populated by ethnic minorities from four main ethnolinguistic1 groups that share common animist beliefs. Most of these villages' inhabitants have been displaced due to conflict or the Government's internal displacement programmes. Their livelihoods depend on a subsistence economy based on agriculture (with rice a staple crop) and livestock breeding, as well as the gathering of edible plants in forest environments, hunting, fishing, or gathering other wild foods. Coping strategies, such as self-sufficiency and then the sharing of food in villages where bartering is common, provide additional local plant and animal foods to the diet.

In this area, the national demographic and health survey (Lao PDR, 2012) identified in 2011 a high rate of stunting for children under five years (53.2%) and worrying levels of wasting (21.2%) and severe wasting (9.2%). This led the WFP to initiate a Mother and Child Health and Nutrition programme, which included the provision of nutrition supplements between 2012 and 2015 to support the nutrition of pregnant and lactating women, as well as infants and young children in their first 24 months (the '1,000 days' period) (WFP, 2016).

The researchers chose this province to interview caregivers, particularly mothers, to understand and hear them describe their feelings and perceptions regarding child nutrition and development. It is important to note that, although the research was conducted in the same area, this study is not an evaluation of the programme implemented by WFP.

Methodology

This research project stems from a tripartite public-private collaboration established from late 2019 to mid-2021 between an independent human science researcher, the Faculty of Public Health at the University of Health Sciences in Vientiane (Laos), and the Nutriset Group.2

A bibliographical research phase was first carried out to inform the design of the research project and to develop the research questions. The interview guide was then compiled and pre-tested. In June 2020, the study protocol received research authorisation from the Ethics Committee of the University of Health Sciences.

In December 2020, three researchers3 conducted data collection in six villages4 of Luang Namtha Province using semi-structured interviews (individual or focus group discussions). They employed an interview guide containing 55 questions covering eight themes, including maternal nutrition and child nutrition and development.

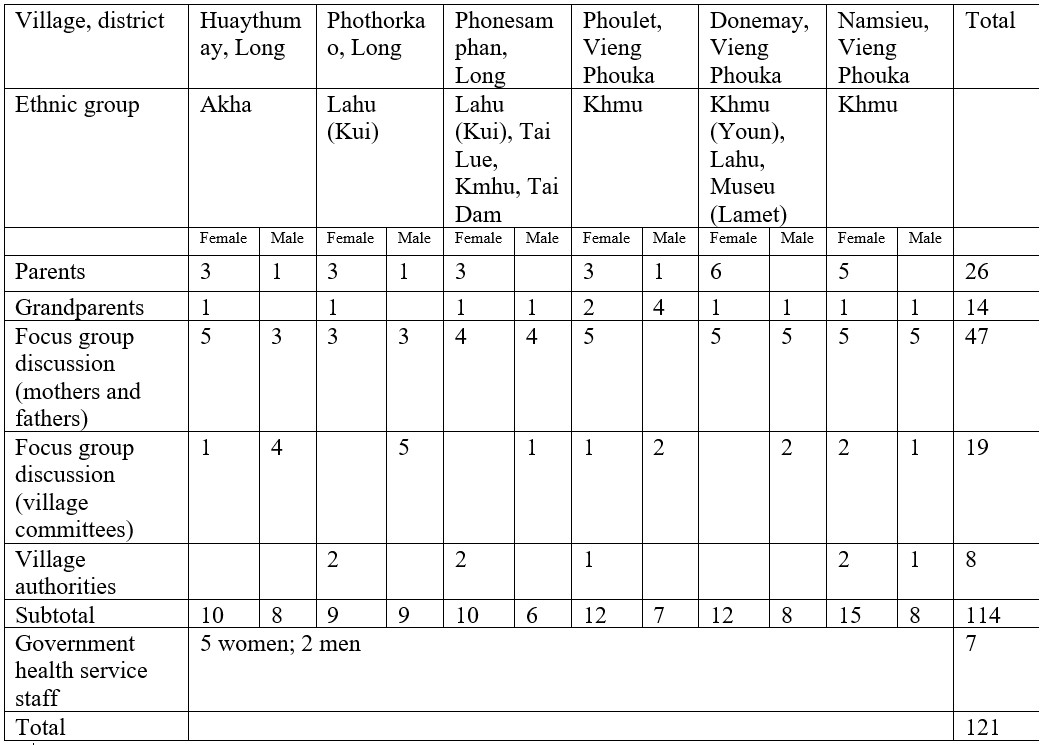

Interviews were carried out with 121 key informants directly or indirectly involved in childcare when the WFP programme was implemented5 (Table 1). The majority (87 people - 57 women and 30 men) were parents or grandparents responsible for childcare and had an influence on children's diets. A further 27 people were considered village authorities (village health volunteers, traditional midwives, members of the Lao Women's Union, and healers) and seven people were government health service staff. The sampling frame consisted of villages. Researchers attempted to ensure the representation of different ethnic groups in multi-ethnic villages.

Table 1: Key informants

Individual interviews and focus group discussions aimed to create an interactive dynamic to allow for more spontaneous data collection. Interviews were either conducted in Lao or through a translator in non-Lao-speaking villages.

The verbatim reports collected were then analysed and grouped by themes under the categories 'nutrition for pregnant and lactating women and their newborns' and 'nutrition for children and their development'.

The data collected considers the concept of a healthy child from the perspective of nutrition and development. Although in practice the data covered more topics, the findings reported here are limited to the main features of child nutrition and the description of 'good' child development.

Findings

Main characteristics of child nutrition in northern Laos

The interviews revealed that, according to ancestral wisdom, breastfeeding should continue until the child is walking and they can start eating solid foods when teeth appear. Complementary feeding begins with rice, which has a strong symbolic and religious significance: rice is considered "good for children; it gives them energy and makes them strong."6

Animal and plant foods, sourced directly from nature, were associated with multiple benefits, such as 'giving strength'. Food of natural origin was contrasted with that produced by intensive agriculture or agroindustry.

"I want him to have as much fruit and natural produce as possible, as well as meat from wild animals" - Extract from an interview with a Lamet mother, regarding her son

Dietary diversity was seen as essential, although putting it into practice in meal preparation depended on the availability of cultivated and/or harvested foods.7 It also appeared that the attention paid to a child's eating habits decreased as the child got older.

Children and their development

In response to the question "How would you describe a well-developed child?", most terms used related to physical appearance: the child was referred to as 'big' or 'strong'8 or even 'fat' or 'brawny'. Fatness (even being overweight) was considered a sign of health and wellbeing, while strength was considered a key quality in mountain environments.

"His skin is not wrinkled", "the child is beautiful" ,"he has a lot of hair“ - Assorted aesthetic terms used to describe children during interviews.

The 'complete' child was often described as the opposite of the malnourished child. In the 'Lessons learned' section, we consider the notions of the 'well-developed' and the 'complete' child.

A few key informants referred to a child's behaviour: two mothers mentioned a child's good temperament and the fact that he did not cry. The child's physical abilities, such as 'walking for a long time', 'running', or 'jumping a long way', were also mentioned.

In the Lahu village, one father mentioned the child's socialisation and tendency to play with others rather than remaining alone. Two mothers referred to a child's good character, good mood, and the fact that they did not cry.

In terms of school education, only five respondents (notably men from Khmu villages) cited the child's intellectual faculties, describing a well-developed child as having a 'good brain' and studying well.

Discussion and lessons learned

Analysis of findings

This study questioned the perception of child development through a comprehensive anthropological approach that integrates the fact that food contributes to the social and biological construction of the child (Bouima, 2021), rather than through the more traditional prism of anthropometry or that of universal 'international standards.' UNICEF, for instance, created the Early Childhood Development Index (Lao PDR, 2012)9 and Forssman et al (2017) developed a method for assessing cognitive development independent of the child's economic, cultural, or educational background. The existing tools are essentially based on psychological or motor examinations of the child.

This study took a different angle and approached child development by collecting and analysing the verbatim accounts of people closest to the child. This study sought to identify new forms of qualitative 'indicators' to describe a child's development. Certain aspects of the perception of potential links between nutrition and child development were explored, with an awareness of the multi-dimensionality of child development - particularly the importance of its emotional and spiritual aspects.

Lessons learned

This study measured the complexity of tackling child development through semantics and the importance of 'speaking the same language' beyond translation. For example, it became clear that the term 'development' was mostly understood as infrastructure development.

In the Lao language, a 'complete' or 'well-developed' child is referred to using the term 'somboon'. This term comes from 'Sampurna' in Sanskrit, which refers to a form of fullness or abundance, which can be literally translated as 'complete' or 'fulfilled' when referring to a child. We noticed that this term, which appeared in the pre-survey, is used in some of the other languages of ethnic groups included in the study.

The interviewees were unfamiliar with the very concept of 'child development', as the elements of children's development are not perceived as connected or evolving in a linear way in the North Lao way of thinking. However, parents could account for what makes a child beautiful or admirable (skin, weight, height, alertness or intelligence, ability to reproduce social cues and socialise, and good health) and to what extent food contributes to this. Use of the local term 'somboon' seemed key to tackling this subject.

This study has shown how parents, driven by the desire to have a 'complete' child, used various food coping strategies in a context of relative precariousness and food insecurity. Certain foods, such as those gathered direct from nature, particularly the forest, had a strong emotional or symbolic significance, reflecting a form of symbiosis between these populations and their environments.

Study limitations

The study did not address the specific culture and beliefs of each of the four ethnolinguistic groups,10 which could have been sensitive in this ethnic minority context.

Based on Natacha Collomb's (2010 and 2011) work in northern Laos, the researchers were interested in exploring the role and importance of the heart and emotions in children's learning and development,11 but this would have been a wider undertaking.

Key barriers

Access to villages was difficult, as some roads had been blocked during the rainy season. Periods of restricted mobility due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 also delayed data collection.

Another barrier was the lack of the researchers' knowledge of local languages, necessitating the presence of a non-professional translator from the community. In addition, some mothers expressed shyness or embarrassment during interviews. Finally, the fact that the study's lead researcher was a man of foreign nationality may have constituted a bias during the interviews, even though he was accompanied by two Lao women.

Conclusion

In a relatively isolated, food-insecure rural context, this study attempted to provide some insights into a parents' understanding of children's growth and development in relation to their diet. The displaced populations in Luang Namtha refer to ancestral knowledge of a diet based on diversified foods of natural origin, which is good for children. The parents also described the characteristics of a well-developed child as 'somboon', a term that represents the child's growth, healthy development, strength, and good health - qualities that seem necessary in forest and mountain environments. Aesthetic features of their face and skin were also highlighted, as were their socialisation and schooling.

These findings confirm the need to take a holistic approach to child development. According to Shonkoff and Philips (2000), physical growth, literacy and numeracy, social and emotional development, and willingness to learn are vital areas of a child's comprehensive development. Collomb's work focuses not only on cognition and brain development, but also on other aspects of emotional and social development. It also seems important to explore the contribution of the spiritual dimension to human fulfilment, here in the context of animist societies.

From our findings, we recommend adopting a comprehensive approach with anthropological considerations when setting up nutrition intervention programmes, with a view to defining strategies that are adapted to the specificities of individual contexts, cultures, and social relations. This study has highlighted the importance of natural food according to both its symbolic and nutritional qualities, which cannot be overlooked when implementing nutritional programmes or offering nutritional solutions.

For more information, please contact Sophie-Anne Sauvegrain at sasauvegrain@nutriset-dev.fr.

References

Bouima S (2021) De l'identité au soin, regard socio-anthropologique sur l'alimentation. Revue de l'infirmiere, 70, 22-24.

Collomb N (2010) Nourrir la vie : éthique de la relation de soin chez les T'ai Dam du Nord Laos. Une étude de la notion polysémique de liang. Mousson, 15, 55-74.

Collomb N (2011) Ce que le cœur sert à penser. Fondements corporels de la cognition, des émotions et de la personnalité chez les T'ai Dam du Nord Laos. L'Homme - Revue française d'anthropologie, 197, 25-40.

Forssman L, Ashorn P, Ashorn U et al (2017) Eye-tracking-based assessment of cognitive function in low-resource settings. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 102, 4, 301-302.

Lao PDR (2012) Lao Social Indicator Survey (LSIS) 2011/12 (Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey / Demographic and Health Survey). dhsprogram.com.

Shonkoff J & Phillips D (2000) From neurons to neighbourhoods: The science of early childhood development. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. scirp.org.

WFP (2016) Country programme Laos (2012-2017) Standard Project Report 2016. World Food Programme in Lao People's Democratic Republic. docs.wfp.org.

1 The four ethnolinguistic groups are the Akha, the Lahu, the Khmu, and the Lamet.

2 Nutriset is a private actor in the response to malnutrition.

3 Two Lao women and a French man.

4 The six villages covered in this study are Huaythumay, Phothorkao, Phonesamphan, Phoulet, Donemay, and Namsieu.

5 Children were aged between six months and two years during programme implementation (2012–2015), which means they were aged 5–10 years during data collection.

6 Mothers used to chew rice before feeding it to their children until hygiene campaigns discouraged this practice.

7 Examples of foods from a diversified diet: cereals (rice, corn), meat (pork, squirrel, duck, chicken), fish, eggs, vegetables (taro, cassava, green vegetables, gourds, etc.) and fruit (palm fruit, pineapple, bananas, rambutan, oranges, apples, etc.).

8 The term ‘strong’ refers to both physical strength and the bodily form.

9 The Early Childhood Development Index is made up of four domains: literacy/numeracy, physical development, social-emotional development, and learning.

10 The Akha, the Lahu, the Khmu, and the Lamet.

11 For the Tai Dam people, beyond the role of the heart in learning, the heart’s feeling is also traditionally used to identify which foods are healthy and which are taboo.