Food-based recommendations for improving complementary feeding in Zimbabwe

Jen Burns Senior Technical Advisor at Helen Keller International, United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Advancing Nutrition

Pamela Ncube-Murakwani Nutrition Lead at International Medical Corps, Amalima Loko

Chris Vogliano Technical Advisor at Helen Keller International, USAID Advancing Nutrition

Lisa Sherburne Director of Social and Behavior Change at John Snow Incorporated, USAID Advancing Nutrition

Shaneka Thurman Senior Technical Advisor at the Manoff Group, USAID Advancing Nutrition

Kavita Sethuraman Director of Nutrition in Humanitarian Contexts at National Cooperative Business Association CLUSA, USAID Advancing Nutrition

We would like to acknowledge the USAID Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance staff who supported this work, namely Mike Manske (Senior Nutrition Advisor), Themba Nduna (Nutrition Adviser, USAID Zimbabwe mission), and Andrea Warren (Nutrition Research Advisor). In addition, we would like to thank the field staff who carried out the participatory work in communities: Patricia Ndebele (Social Behaviour Change Lead), Tinashe Marange (Monitoring Evaluation and Learning Coordinator), Priviledge Manenji (Nutrition Coordinator), Bekezela Ncube (Nutrition Coordinator), Talent Mpofu (Graduate Nutrition Intern).

What we know: In Zimbabwe, approximately 11% of children aged 6–23 months receive a minimum acceptable diet and less than 68% of children receive the minimum meal frequency for their age. In Matabeleland North Province, only 5% of children aged 6–23 months receive a minimum acceptable diet, and using locally available, nutrient-rich foods remains a challenge for caregivers.

What this adds: Using a participatory, community-based approach, we identified and tested a menu of food-based recommendations for young children, with caregivers, and supportive practices from various household members. The menu of primarily indigenous food options, recommended by age, permits caregivers to choose foods that are available, accessible, and culturally acceptable to improve complementary feeding practices at the household level. This goes beyond traditional programmatic messaging and cooking demonstrations.

Background

The USAID-funded ‘Amalima Loko’ is a five-year (2020–2025) programme operating in five districts (Binga, Hwange, Lupane, Nkayi, and Tsholotsho) of Zimbabwe’s Matabeleland North Province. Amalima Loko aims to improve the nutritional status of and practices among women of reproductive age and children aged under five years. As part of a package of multi-sectoral efforts to improve nutrition outcomes, Amalima Loko envisioned developing local food-based recommendations and other supportive behaviours that utilise nutrient-rich, locally available indigenous foods. Between September 2022 and March 2023, USAID Advancing Nutrition provided the Amalima Loko programme with technical assistance to identify the recommendations that caregivers can use at the household level to improve complementary feeding.

Methodology

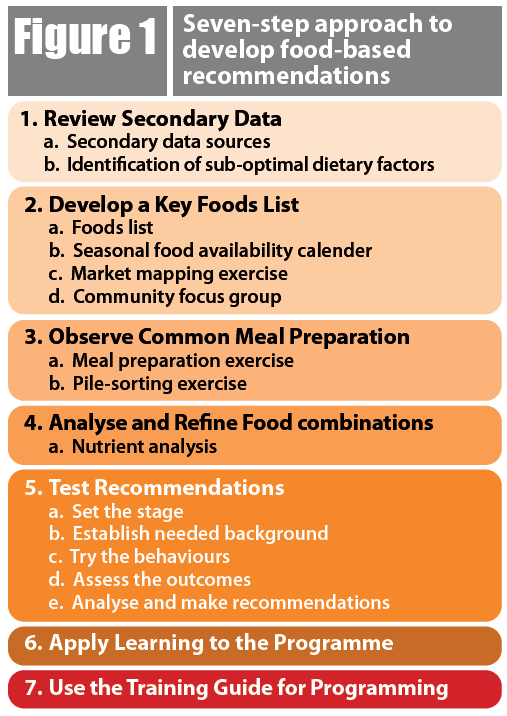

The Amalima Loko team used a seven-step approach (Figure 1), starting with a review of secondary data sources. As a second step, a ‘Key Foods List’ was developed based on several resources, including seasonal availability calendars, market surveys, and community focus group discussions, to identify foods which are locally available. Using the Key Foods List, meal preparation exercises were then carried out to observe the making of typical meals and to gather data for use in developing modifications to current feeding practices. A pile-sorting exercise was used to explore current practices and perceptions around food preparation and feeding practices.

Figure 1: Seven-step approach to develop food-based recommendations

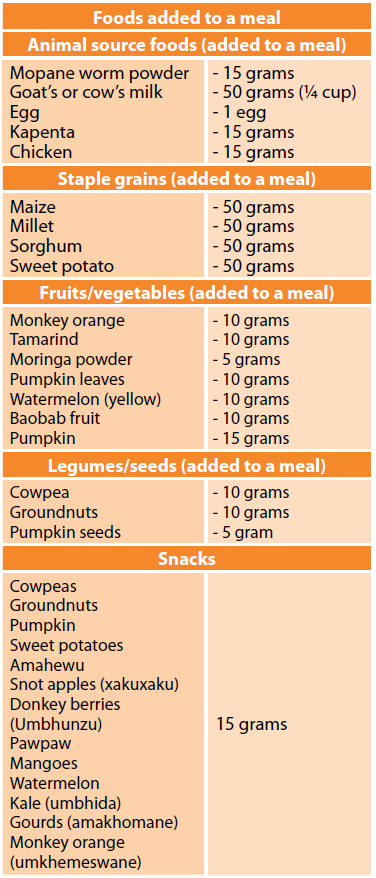

Using an Excel-based analytical tool1, specific types and amounts of foods were analysed to identify combinations with improved nutrient content. The types and quantities of food were then organised in a table by food group, to reflect a menu of foods that would meaningfully contribute to filling nutrient gaps (iron, vitamin A, and other nutrients, like zinc and calcium) for those aged 6–11 months and 12–23 months. This menu was used to offer suggestions to caregivers for foods and quantities that could be added to the child’s own bowl of a typical meal or consumed as a snack (Table 1).

Table 1: Example menu of foods that could be added to a child’s diet (aged 6–11 months)

In addition to the menu of foods, USAID Advancing Nutrition developed guidance that could be offered to caregivers on the appropriate quantity of food per meal, frequency of meals, and variety of nutrient-rich foods for both meals and snacks, conforming to the needs by age group (Box 1). With this, a list of tasks that various household members could carry out to support optimal young child feeding was also developed.

Box 1: Example guidance on foods and supportive behaviours for a child aged 6–11 months1. Prepare porridge or sadza, based on a staple available in your household. |

The menu of suggested foods and potential recommendations were then tested using the Trials of Improved Practices (TIPs) methodology, a formative research technique that tests and refines recommended practices over a series of household visits in a collaborative way to reach agreed solutions. In total, 32 households tried new or modified behaviours around dietary diversity, frequency of feeding, amount of food, and caregiver roles in young child feeding to determine which were the most feasible and acceptable. Constraints on participants’ willingness to change behaviours were also investigated through the behavioural trials, as well as their motivations for trying and sustaining the new practices.

Findings

Overall, we found that this approach worked to identify and tailor food-based recommendations to the local contexts. Results from the TIPs indicated that many of the recommendations were both feasible and acceptable. The learning generated at each stage of the seven-step approach informed food-based recommendations related to dietary diversity, meal frequency, and food amounts, as well as influencing factors.

Initially, we found that children's meals often consisted of a staple (grains) and one, or sometimes two, additional foods – often plant based. Children aged 6–11 months typically received starchy and less diverse meals, whereas older children were offered more diverse food, sometimes including animal source foods. Across all age groups, children received two to three meals per day, depending on food availability and caregiver’s availability. Age-specific knowledge regarding the amount of food to offer to a child was low, and caregivers typically did not measure food when cooking and serving children. Children usually received meals from their own bowl and plate.

Communities shared additional barriers to feeding local and indigenous foods, notably in regard to caregiver’s time, food preparation and processing skills, and limited decision-making around purchasing food. Men primarily manage household income and make decisions around purchasing or selling livestock. Other household members are also involved in decisions around food purchasing, preparation, and the actual feeding of young children. For example, grandmothers, aunts, or older siblings will help with the actual feeding of young children when the mother is away or busy with chores. In addition, certain cultural beliefs – including around eggs causing epilepsy or affecting children’s teeth, meat causing greediness, and peanut butter affecting the reproductive system – restrict what caregivers feed children. Religion also influences nutrition and health practices, as well as perceptions of indigenous foods. Communities noted perceptions of indigenous foods being valued because they are available for all people to consume, do not have to be purchased, and are considered “healthy”; however, some are viewed as “poor people’s foods,” a people expressed little desire to gather them. The Amalima Loko programme utilised these findings to develop community nutrition dialogues. These bring together influential community members, caregivers, and other family members to discuss specific issues, dispel myths and misconceptions, and foster a supportive, enabling environment for recommended practices to be adopted.

Successes

It was possible for caregivers to improve complementary feeding practices using locally available foods, provided they could access seasonally available foods, had the knowledge, skills, and time to prepare them, and had family and community support for putting the behaviours into practice.

During household trials, caregivers were willing and able to use a menu of options to add animal source foods, legumes, fruits, and vegetables to their child’s meals, as well as offering snacks between meals. Caregivers were also willing to measure foods when cooking and to serve children appropriate amounts of food. Cultural beliefs around foods in different communities continued to influence those that caregivers are willing to try to offer children, making the menu of options critical. Offering the menu of food options permitted households to identify what works for them based on what is available and their own resources. Furthermore, when caregivers received the support of other household members to try a new food, households were more successful. One woman stated that other wives can work the grinding mill to produce readily available flours. Another stated the husband purchased peanut butter, which allowed her to add it to the porridge.

“The food-based recommendations are great. It’s easy for mothers to learn through the practical cooking sessions. Each meal they give to the children is enriched with nutritious ingredients such as umviyo (an indigenous fruit)” – Mother in Lupane district

“Before I gained all this knowledge, I would just prepare porridge for my child without enriching it. Now I add two different ingredients from different food groups. My baby loves the porridge. She is healthy, happy and strong – and that makes me happy” – Mother in Lupane district

Amalima Loko now implements the findings through a simple, clear, and easy-to-use recipe guide for over 36,000 caregivers. The guide offers the menu of options for household use and community cooking sessions with care groups and encourages caregivers to creatively use local foods to improve children’s diets.

“Mothers are confident when it comes to preparing nutritious meals [now]…The babies are healthy and happy and the mothers cannot stop talking about the different kinds of recipes they are coming up with!” – Priviledge Manenji, Amalima Loko Nutrition Coordinator

The activity is supported by a series of lively community dialogues on child feeding and the engagement of ‘male champions’ who support childcare and feeding. Male champions learn and practice how to enrich young children's porridge with local foods such as milk and juice from an indigenous fruit, umkhemeswane.

Challenges

Programme interventions were adapted to address challenges. To address cultural restrictions, especially in one district around feeding eggs to young children, the programme organised multiple community dialogues and an interactive forum theatre with influential family members – including grandmothers who uphold the norms. Some caregivers found that their children did not like the taste of mopane worm powder. To improve palatability for children, the programme adjusted recommendations to encourage mixing the powder with other ingredients. Seasonal availability continues to be another challenge. The programme promotes sun drying of vegetables and some indigenous fruits and pounding these into a powder that is then used to enrich the child's food. In addition, supporting farmers’ groups to sun dry pumpkin seeds and nuts has helped to address year-round availability.

Lessons learned

Important lessons for improving young children’s diets emerged from this experience. First, the Key Foods List demonstrates how even small amounts of indigenous foods can contribute significantly to meeting the nutrient requirements of children aged 6–11 and 12–23 months. This learning contributes to the growing evidence base on the role of indigenous foods in ensuring an affordable, accessible, and nutritionally adequate diet (Termote et al., 2014; Ruzengwe et al., 2022). It also highlights how ongoing natural resource management efforts, undertaken to conserve wild food resources by communities and supported through the programme, are essential for young child feeding as well as other nutrition and livelihood goals.

The seven-step approach can be used by any programme to translate a key foods list of indigenous foods into a menu of locally acceptable foods that communities and caregivers are willing and able to use to improve young children’s diets through meals and snacks. The participatory approach with communities, caregivers, and their families was necessary to contextualise the programme’s Key Foods List and develop the menu of options. Caregivers’ real experiences helped identify practical and feasible solutions that mothers were keen to adopt. It is worth noting that, while the focus of this work was on food-based recommendations for children aged 6–23 months, programmes should also promote continued breastfeeding through to age two years and beyond. Breastmilk remains an essential source of energy and nutrients for this age group.

Finally, the move away from standard recipes to a menu of options from which caregivers could select based on seasonal availability, child’s taste and preference, and other personal choices is a lesson learned from caregivers themselves.

Conclusion

Drawing on global best practice, and responding to the needs of many implementing partners of infant and young child feeding programmes, this experience offers a template for working to improve children’s diets. Multi-sectoral nutrition programmes carrying out community-based work could apply the same approach to develop context-specific, locally acceptable, and feasible food-based recommendations to improve the diets of young children, and move away from providing food transfers.

For more information, please contact Jen Burns at jbarr5@yahoo.com

References

Ruzengwe F, Nyarugwe S, Manditsera F et al. (2022) Contribution of edible insects to improved food and nutrition security: A review. International Journal of Food Science & Technology, 57, 10, 6257–6269.

Termote C, Raneri J, Deptford A et al. (2014) Assessing the potential of wild foods to reduce the cost of a nutritionally adequate diet: An example from Eastern Baringo District, Kenya. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 35, 4, 458–479.

Jump to section

About This Article

Download & Citation

Reference this page

Jen Burns, Pamela Ncube-Murakwani, Chris Vogliano, Lisa Sherburne, Shaneka Thurman and Kavita Sethuraman (2024). Food-based recommendations for improving complementary feeding in Zimbabwe. Field Exchange Magazine 72. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25461385