Mozambique: Behaviour change interventions increase production of vitamin A rich foods

Jurgita Slekiene PostDoc at the Department of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry and Psychosomatic Medicine, University Hospital Zurich, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland; and Ranas Ltd, Zurich, Switzerland

Hans Mosler CEO of RanasMosler, Switzerland

Alice Costa Natural Resources Expert and Development Project Coordinator at Istituto Oikos, Mozambique

Arina de Fatima Momade Nutritionist and Community Engagement Expert at Istituto Oikos, Mozambique

John Brogan Water and Sanitation Advisor at Helvetas, Switzerland

Nicolas Morand Programme Advisor at Helvetas, Madagascar and Mozambique

What we know: Nearly 800,000 people live in a situation of displacement in the province of Cabo Delgado in northern Mozambique, resulting from armed conflicts (since 2017) and the destruction caused by Cyclone Kenneth (in 2019) (IOM, 2022). The district of Mecufi, a southern district of Cabo Delgado, has poor access to basic services, elevated unemployment, and high levels of malnutrition (coinciding with a reduction in humanitarian food assistance programmes).

What this adds: We designed a project aiming to increase access to and consumption of safe and nutritious foods by evaluating possible behaviour change interventions. Growing pumpkins and drying ripe mangoes (instead of drying unripe mangoes, which are low in vitamin A – the standard practice of many households) improved access to vitamin A rich food.

Setting the scene

This project was funded by the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) and implemented in 2020 and 2021 by partners working alongside the District Government of Mecufi. In total, 60 mothers of malnourished children and 100 smallholder farmers benefitted by improving their knowledge on sustainable food production and the appropriate consumption of self-produced fruit and vegetables.

Instituto Oikos is an Italian non-governmental organisation that has worked in Mozambique since 2012, developing projects in Cabo Delgado to support institutions and people to enhance their capacity to face the impact of climate change on natural resources and communities. Oikos collected data pre- and post-intervention and collaborated with RanasMosler to analyse the context, design the programme, and provide technical support.

Helvetas is an independent development organisation based in Switzerland, with affiliated organisations in Germany and the US. Helvetas works to alleviate poverty and advance human rights in almost 40 developing and transitional countries across Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe. Helvetas guided Oikos to use a behaviour change approach – Risks, Attitudes, Norms, Abilities, and Self-regulation (RANAS) – to design their nutrition programme, train field teams, and to lead implementation. RanasMosler was founded as a spin-off collaboration of the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology and has helped pioneer the RANAS approach. RanasMosler measured changes in behaviour, intention, and behavioural factors, with results that form the basis of this article.

Methods

Oikos conducted a 24-hour dietary recall survey in 60 households with children aged under five years. Results showed that low consumption of vitamin A rich foods was a major driver of poor diets. We identified two interventions that had the potential to tackle this: a) growing pumpkins; and b) drying ripe mangos (Box 1). The drying of mango is traditionally limited to green mangoes, which have lower nutrient density compared to the ripe fruit, in Northern Mozambique.

Box 1: The interventionsGrowing pumpkins Training included pumpkin growing techniques in homestead gardens and planning workload using an annual agronomic calendar. Each participant family received a flag to be put in their garden to recognise their efforts and to prompt goal setting. Next, we described the benefits in terms of both health and livelihoods that growing and consuming pumpkins may have. Each family received technical support on subjects such as water management, pest control, soil amelioration, seed production, and conservation. In the final step, radio spots (10-minute radio shows in which nutritional and sustainable agricultural messages were disseminated) and debates created a positive group identity and reinforced the importance of consuming vitamin A rich foods. Drying ripe mangos Two Oikos agronomists trained participants on the techniques to dry ripe mango instead of unripe mangos. In group discussions with study participants, an Oikos nutritionist then led the tasting of dried mango and shared recipes. Any barriers identified were discussed between agronomists and nutritionists to find solutions to support participants to plan and practice target behaviours. |

We collected quantitative data regarding homestead food production of vitamin A rich foods, to develop behaviour change interventions. We applied the RANAS approach (Mosler, 2012; Mosler & Contzen, 2016), which offers an evidence-based method to identify and measure relevant psychosocial factors to change, then design and evaluate behaviour change interventions and strategies in the public health sector. The applicability of the RANAS approach has been demonstrated in previous research in more than 30 countries.1

The baseline survey (N=200) was conducted in October 2020. A quantitative questionnaire based on the RANAS model was used to collect data on the two target behaviours – i.e., growing pumpkins and drying ripe mangos – and the psychosocial factors underlying those target behaviours, by performing face-to-face interviews in households. Baseline study results informed the behaviour change interventions, although these findings are beyond the scope of this article. The RANAS practical guide2 was used to develop a behaviour change strategy.

Behaviour change interventions were implemented from November 2020 to February 2021. Funding limitations prevented this study from continuing for a longer period, but this timeframe was suitable to observe the growth of both mangoes (90–150 days) and pumpkins (85–120 days), which were central to this intervention. The Oikos team developed a four-step behaviour change strategy and trained groups of 15–20 women, involving 160 households in total (100 households in sustainable agriculture and 60 households in nutrition activities) (Box 1).

Collecting follow-up data

Follow-up data was collected in February 2021, with face-to-face interviews conducted with the same baseline participants. The quantitative questionnaire, based on the RANAS model, was used to collect data on the target behaviours and the psychosocial factors underlying those target behaviours.

Evaluation analysis

The differences between baseline and follow-up data, for intention to grow pumpkin and to dry ripe mangos, as well as the contextual and behavioural factors underlying target behaviours, were analysed using T-tests for dependent samples, at a 5% significance level. Where five-point response scales were used, variables were considered as an ‘interval scale’ and differences in means were calculated. We acknowledge that there is some debate regarding the use of Likert scales as interval-scale continuous measurements (Sullivan & Artino, 2013). Although the use of an 11-point scale is sometimes recommended (Wu & Leung, 2017), we opted to use a five-point scale in this setting due to ease of comprehension (for respondents), accurate administration (by researchers), and the nature of the data being analysed.

Growing pumpkins

Growing pumpkins or other vegetables requires the availability of a home garden (or field) and around 24.1% of families cultivated in their homestead at baseline. The cultivation of a home garden increased significantly (to 47.9%) after the intervention. The cultivation of fields was already very high at baseline (99.1%) and reached 100% at follow-up.

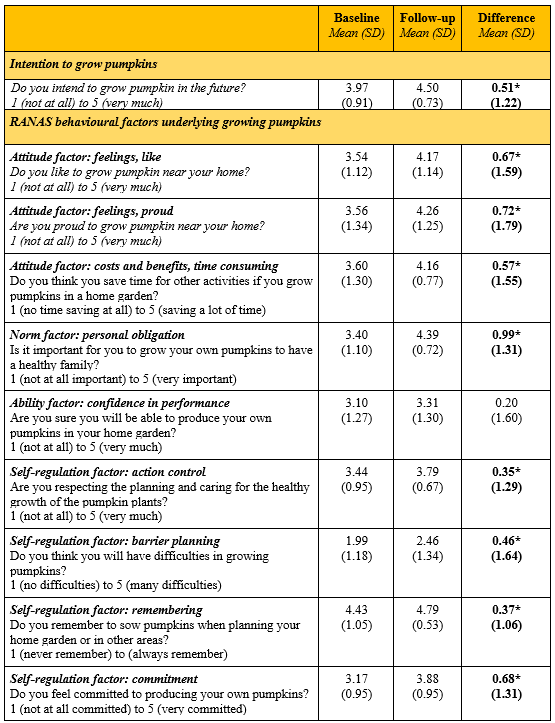

There were significant differences between baseline and follow-up surveys regarding intention to grow pumpkins. The RANAS factors for growing pumpkins targeted with the behaviour change intervention showed significant differences between the baseline and follow-up surveys, with the exception of the ability factor ‘confidence in performance’, which did not significantly change (Table 1).

Table 1: Changes in context, intention, and behavioural factors underlying growing pumpkins

N=104-121 *p ≤ .05

Only factors that were targeted with behaviour change interventions were included in the analysis.

Drying ripe mangos

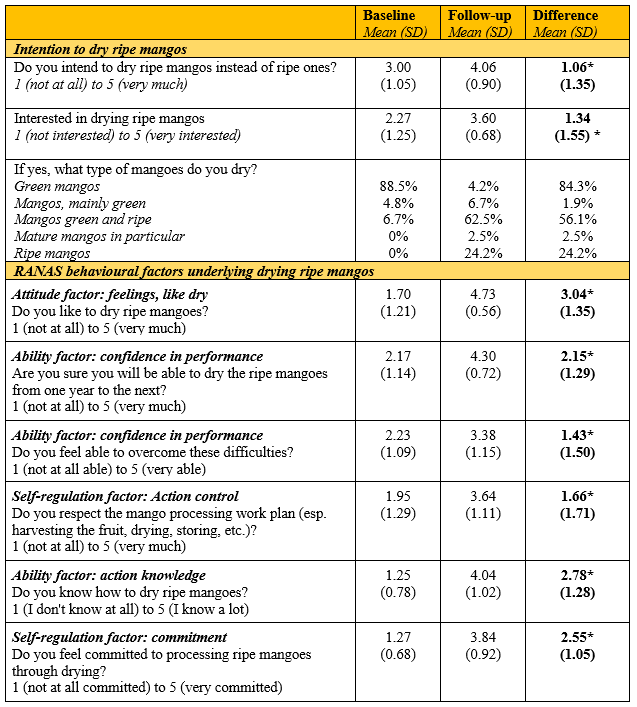

Drying mangoes was an already common practice in the study group at baseline (89.7%), but increased in popularity post-intervention (99.2%). More specifically, interest and intention to dry ripe mangos increased significantly at follow-up compared to baseline (Table 2). At baseline, 0% of respondents reported that they knew the advantages and disadvantages of drying ripe mango, which increased to 93.4% and 63.6%, respectively. The drying of other vegetables and fruits increased by 20% at follow-up, compared to baseline (36.2% to 56.2%) – a complementary outcome of the intervention. Knowledge about the differences between drying ripe and unripe mangos increased from 4.3% to 91.7%. All RANAS factors for drying ripe mango that were targeted with behaviour change interventions showed significant differences between the baseline and follow-up surveys (Table 2).

Table 2: Changes in the behaviour, intention, and behavioural factors underlying drying ripe mangos

N=98-121 *p ≤ .05

Only factors that were targeted with behaviour change interventions were included in the analysis

Discussion

We observed that the cultivation of home gardens for growing pumpkins increased significantly post-intervention. However, only half the participants reported that they cultivated their home garden after the behaviour change intervention. The intention of participants to grow pumpkins, as well as almost all targeted behavioural factors, increased significantly post-intervention – but we discovered that participant confidence (to practice the behaviour) did not change with the intervention. This mirrors findings in the self-regulation factor, specifically ‘barrier planning’, which showed an increase in the perception of barriers to growing pumpkins post-intervention. Possible reasons for this are beyond the scope of the study and would require further examination. Given the short time scale of the study, the validity of findings related to enhancing the 'remembering' factor would benefit from confirmation through a longer observation period.

Our interventions resulted in significant, positive changes in regard to drying ripe mangos – specifically, interest in drying ripe mangos and all associated behavioural factors. However, over half of respondents still reported drying both raw and ripe mangos, with only a quarter practicing the desired behaviour of drying only ripe mangos after the intervention. Raw mango is an important ingredient for many traditional dishes and trade-offs in terms of shelf life, transportability, and market demand make drying unripe mangoes a more practical choice for many people in Mozambique.

Participants increased their understanding of better dietary strategies (e.g., they could easily use home courtyards as gardens for growing pumpkins, or they discovered the advantages of drying ripe mangos to improve vitamin A intake). Through an in-depth analysis of the presence/absence of the behaviour in the target community, we were able to design a project that was adapted to the specific context and to focus on relevant interventions to strengthen the technical capacities needed to adopt a new behaviour, such as increasing the commitment to perform the behaviour, enabling the participants to plan and control their progress, and sharing feelings.

Our study reinforced the usefulness of the RANAS evidence-based behaviour change approach in developing a behaviour change intervention and to quantify any changes observed. To build upon the approach described above, it may be useful to develop a concise and ready-to-use questionnaire and analysis tool that can be easily integrated into project baseline questionnaires. This can also provide important methodological guidance, based on the RANAS approach, considering the psychological factors present in the target community.

The RANAS approach has several characteristics that distinguish it from other behaviour change approaches. First, it is grounded in psychological theory whereby the factors that are relevant for behaviour change are clearly defined by the psychological research evidence base. Second, RANAS defines which behaviour change techniques are suitable for each factor, providing a more tailored approach. Third, RANAS uses quantitative data and statistical analysis for defining which behavioural factors must be changed in a specific context. Fourth, RANAS is adapted to (and has been proven for) low- and middle-income settings. Additionally, the RANAS approach can be applied to any behaviour, whereas other approaches may be restricted to only particular behaviours (e.g., handwashing, toilet building, etc.).

Social and behaviour change communication should only be applied when it is possible for people to behave in a desired way. To promote handwashing, it is only reasonable if water and soap are available. If infrastructure is provided, such approaches are cost-effective and can be easily scaled up using appropriate communication channels.

Conclusion

The RANAS behaviour change interventions were successful in increasing access to vitamin A rich foods, through growing pumpkins and drying ripe mangoes, and in changing RANAS factors targeted with the behaviour change intervention. The results of the project confirmed that, by using evidence-based behaviour change interventions adapted to the cultural context, important improvements in nutrition behaviours can be achieved. We recommend including evidence-based behaviour change approaches, such as the RANAS approach, in future Helvetas and Istituto Oikos interventions. We also hope that the design, methodology, and results from this complex, low-income setting can act as useful guidance for those looking to apply the same strategies in their own areas of work.

For more information, please contact John Brogan at John.Brogan@helvetas.org.

References

IOM (2022) Global data institute displacement tracking index – Mozambique (as at February 2022). dtm.iom.int.

Mosler HJ (2012) A systematic approach to behaviour change interventions for the water and sanitation sector in developing countries: A conceptual model, a review, and a guideline. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 22, 5, 431–449.

Mosler HJ and Contzen N (2016) Systematic behaviour change in water, sanitation, and hygiene. A practical guide using the RANAS approach. Version 1.1. ranasmosler.com.

Sullivan G & Artino A (2013) Analyzing and interpreting data from Likert-type scales. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 5, 4, 541–542.

Wu H & Leung S (2017) Can Likert scales be treated as interval scales? – A simulation study. Journal of Social Service Research, 43, 4, 527–532.

About This Article

Jump to section

Download & Citation

Reference this page

Jurgita Slekiene, Hans Mosler, Alice Costa, Arina de Fatima Momade, John Brogan and Nicolas Morand (2024). Mozambique: Behaviour change interventions increase production of vitamin A rich foods. Field Exchange 72. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25461577