Feeding hope: The crucial role of nutrition in cleft care

Barbara Delage Director of Global Nutrition Programmes at Smile Train Inc.

Joe Bwija Kasengi Paediatrician at Hôpital Provincial Général de Référence de Bukavu, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)

Danny Loanie General Practitioner at Polyclinique du Millénaire, Kisangani, DRC

What we know: Current understanding emphasises the importance of surgical interventions for children with orofacial clefts, particularly in low-resource settings where surgery can significantly improve a child's quality of life. However, this surgical-centric mindset often neglects the critical need for immediate nutritional support and education for mothers, which are essential for preventing malnutrition and ensuring optimal growth and development.

What this article adds: This article highlights the significant gaps in the continuum of care for children with clefts, showcasing real-life cases that illustrate the consequences of inadequate feeding support and the urgent need for early interventions. The stories shared underscore the importance of prioritising breastfeeding and nutritional care from birth and advocating for a more comprehensive approach that includes both nutritional and surgical interventions.

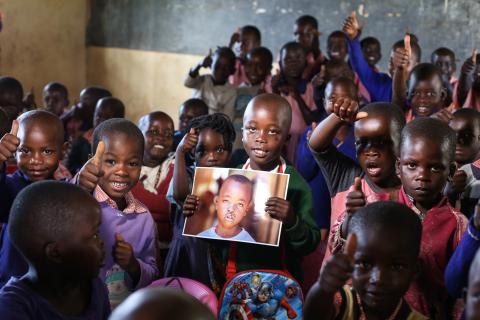

Smile Train is the world’s largest non-governmental organisation focusing on transforming the lives of individuals affected by cleft lips and palates. With a presence in over 70 countries, they have been instrumental in providing free surgical care and other services to children in need. However, despite these efforts, the journey of care for children with clefts is often complicated by nutritional challenges.

Orofacial clefts are common birth defects which occur in about one in 700 live births, with a higher burden in low-income countries (Wang et al, 2023). They are characterised by an opening of the upper lip (cleft lip) and/or of the roof of the mouth (cleft palate) (Kadir et al, 2017). Resulting from defective tissue fusion early in pregnancy, cleft lip and palate have a multifactorial and intricate aetiology that makes it difficult to predict and prevent their occurrence. Optimal care focuses on addressing the unique and varied needs of individuals through an interdisciplinary approach (Frederick et al, 2022).

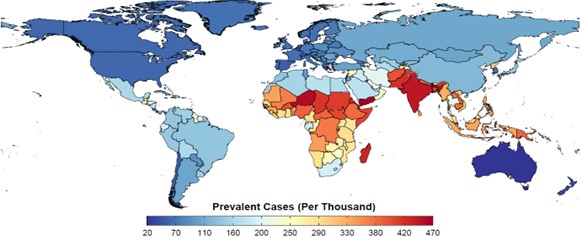

Children born with clefts are at a higher risk of malnutrition, particularly in resource-limited settings (Figure 1). Globally, children with clefts aged under five years are more than twice as likely to be underweight compared to the general under-five population (IHME & Smile Train, 2022). Malnutrition not only compromises the short- and long-term health of these children but also leads to delays in critical treatments, including surgery. Malnourished children face increased risk of complications during anaesthesia and surgery, as well as higher risk of poor healing. Delaying effective care further increases the risk of irreversible damage, such as hearing loss, communication difficulties, and social challenges.

Figure 1: Map of excess underweight prevalence for those with cleftsa

a Children aged <5 years. Data from 2020

Malnutrition is often primarily attributed to the functional challenges of feeding and swallowing caused by the presence of the cleft itself. However, these issues are not the only factors contributing to the excess malnutrition in children with clefts in resource-constrained settings. As Chung et al (2019) highlighted, the stigma faced by children with clefts, which frequently delays their access to healthcare, plays a significant role. Additionally, healthcare systems in these settings are often under-resourced and ill-equipped to provide adequate support to caregivers and their children. The combination of social stigma and an inadequate healthcare response exacerbates the risk of malnutrition.

Apollo and Cikuru’s stories: born with cleft lip and palate in DRC

Baby Apollo

Apollo was born with a bilateral cleft lip and palate into a family of farmers displaced by the armed conflict in South-Kivu province. At the health centre where he was born, his mother was discouraged from breastfeeding as staff believed that “the child would not be able to breastfeed”. Consequently, he was fed raw cow’s milk. He missed vaccinations due to failure to thrive, progressively losing weight and developing chronic febrile respiratory infections. At age seven months, severely wasted and stunted, Apollo was referred to the Hȏpital Provincial Général de Réferénce de Bukavu, a Smile Train partner. Inpatient care was initiated, focusing on managing his infections and severe wasting. Due to a lack of therapeutic milk, he was fed commercial infant formula, starting with 75 kcal/kg/day, gradually increasing to 150 kcal/kg/day. Despite antibiotic therapy, Apollo’s condition worsened, and he was diagnosed with acute tuberculous pneumonia. He was treated with the standard anti-tuberculosis quadruple regimen (isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol), along with vitamin B6 supplementation and oxygen therapy, which resolved his lung infection.

Following the national protocol for the integrated management of acute malnutrition, and in the absence of readily available therapeutic foods, Apollo’s caloric intake was increased to 200 kcal/kg/day using milk and masoso porridge (a maize-soy-sorghum blend with added oil and sugar). After two months in the hospital, he recovered from pneumonia and malnutrition.

By nine months, Apollo’s health status had improved enough for him to safely undergo cleft lip surgery in November 2023. Unfortunately, despite multiple attempts to contact and locate the family, Apollo was lost to follow-up before his cleft palate surgery could be completed.

Baby Cikuru

Cikuru and her twin sister were born in Bukavu in November 2022. The babies were delivered at a local health centre and referred to Bukavu Hospital two days later for further evaluation. Unlike her sister, Cikuru was born with a cleft lip and palate. She was also smaller at birth, weighing just 2.04 kg and measuring 48 cm in length. Their mother had begun breastfeeding them both, with healthcare staff advising her to express milk directly into Cikuru’s mouth to ensure adequate nutrition. Since Cikuru’s twin sister could breastfeed effectively, breast milk supply was maintained, making it possible for both babies to be exclusively breastfed.

At their follow-up visit 20 days later, the paediatrician observed that Cikuru was catching up in growth. However, her twin sister Cito born weighing 2.8kg, was not gaining as much weight as expected. The mother was counselled to ensure both babies received hindmilk, which is richer in calories. She was also taught proper techniques for manual breast milk expression and storage, and family members supported by spoon-feeding Cikuru.

By two months, Cikuru had caught up, weighing 3.73 kg and had grown to 54 cm in length. In April 2023, aged five months, she was healthy enough to undergo surgery to repair her cleft lip. However, despite the need for ongoing growth and health monitoring, Cikuru’s mother did not return to the hospital until August 2023, when Cikuru was nine months old, as advised by the surgeon. During this visit, Cikuru was diagnosed with bronchiolitis, delaying her second surgery by one week for treatment to be completed.

Identified gaps

Our experiences at Smile Train reveal significant gaps in the continuum of care for children with orofacial clefts in resource-limited settings, as exemplified in the cases of Apollo and Cikuru. Apollo, born with a bilateral cleft lip and palate, suffered from poor feeding advice, malnutrition, missed vaccinations, and a serious respiratory infection. The lack of skilled feeding support for his mother delayed proper nutrition and surgery. Cikuru’s story shows the importance of early intervention: in her case, the breastfeeding advice supported her growth, but her experience underscores the need for better coordination and consistent follow-up in cleft care. These gaps, observed firsthand at Smile Train, are common in the field but are rarely documented in published reports or research.

No prioritisation of breastfeeding and breastmilk feeding

The benefits of breastfeeding in reducing mortality and illness among children with clefts are frequently underestimated. Besides the compelling short- and long-term benefits for the health, growth, and development of children (Victora et al, 2016), breastfeeding has been associated with fewer middle ear infections and less nasal inflammation caused by milk reflux. Both of these are common in children with a cleft palate (Aniansson et al, 2002). Additionally, breastfeeding stimulates the muscles that are important for the development of oral sensory motor functions, such as speech and language, which are often affected in children with clefts (Abida et al, 2020). In resource-limited settings health professionals are often unfamiliar with the importance of prioritising breastfeeding for infants with clefts, and they may lack the skills needed to support mothers in this process. As a result, they disproportionately recommend commercial milk formula and bottle feeding, which is unsafe in these environments and may displace breast milk. A qualitative study conducted at a cleft treatment centre in Colombia found that mothers felt that health professionals behaved as though breastfeeding was impossible (Ceron-Zapata et al, 2022). While children with cleft lips can often breastfeed effectively when mothers are encouraged and supported, those with a cleft palate may struggle to generate the intraoral suction needed to draw milk from the breast. This challenge often leads to interventions, such as nasogastric tube feeding or the use of bottles or syringes, that neglect skin-to-skin contact and stimulation of breastmilk production.

Challenges in adopting safe feeding practices for infants with clefts

The lack of expert consensus and formal guidance leads health professionals to disregard recommended infant and young child feeding practices, undermining breastfeeding for infants with clefts. While bottle feeding is preferred in high-income settings, it is often adopted in resource-limited areas where it is unsafe. The World Health Organization recommends cup feeding, but it remains underutilised, compromising safe feeding in environments with limited clean water and sanitation.

Surgery-centric care

Surgical repair is vital for treating cleft lip and palate, helping a child eat, speak, and develop properly while also achieving cosmetically pleasing results. Surgeries are typically performed from three months of age for a cleft lip and after nine months for a cleft palate. However, in resource-limited settings, cleft care often prioritises surgery while neglecting critical early interventions. Nutritional interventions are often viewed merely as a way to prepare patients for surgery, missing opportunities to provide immediate feeding counselling and support and promote healthy growth from the start. This surgery-centred approach delays essential care and reflects broader gaps in healthcare systems.

Limited growth monitoring and promotion

A major shortcoming of surgery-centric care is the lack of regular growth assessment in cleft care management. Current practice focuses heavily on a single-point-in-time measure, usually weight-for-age. This narrow focus can mean children who are experiencing growth faltering but are not yet underweight are overlooked, thereby missing the chance to intervene before malnutrition occurs. Moreover, in limited-resource settings, linear growth retardation is a major contributor to low weight-for-age. Without considering a child’s length or height, weight-for-age can be misleading, as it ignores the fact that a shorter child is expected to weigh less than a taller one at the same age (Gorstein et al, 1994). Additionally, in systems that emphasise nutritional status over growth status, the lack of visible malnutrition is sometimes mistakenly seen as a sign of readiness for surgery. This misinterpretation can compromise surgical safety and overlook the need to support a child's overall physical and cognitive development.

Addressing the gaps: Smile Train’s comprehensive cleft care

Smile Train focuses on enhancing the quality of care provided by cleft teams and treatment centres, recognising that comprehensive cleft care extends beyond surgery. Our approach aims to build stronger teams and nutrition support from day one and focuses on three key areas:

Advocacy for feeding and nutrition care from the first point of contact

We advocate for the prioritisation of feeding and nutrition care from the moment a child with a cleft first presents at a treatment centre. This includes urging cleft teams to onboard nutritionists and paediatricians as integral members, ensuring that each child receives the specialised care needed to address feeding difficulties and promote healthy growth.

Building capacity for nutritionists and allied health professionals

We are committed to training nutritionists and allied health professionals involved in cleft care, focusing on breastfeeding support, and growth monitoring and promotion, to ensure optimal nutritional support for children with clefts.

Improving collaboration among cleft team members for better coordinated care

Recognising that the best outcomes are achieved through coordinated care, Smile Train also focuses on improving team dynamics within cleft care teams. We facilitate training to strengthen collaboration and communication among the various specialist disciplines involved in cleft care, ensuring cohesive care for a child’s well-being.

Call for broad health system improvements

While targeted interventions at the cleft team level are crucial, addressing the broader shortcomings in managing children with clefts from birth requires systemic change at the national level. This calls for countries to improve the quality of their healthcare systems to better support these vulnerable children and their families (Kruk et al, 2018). Key actions may include the following:

Enhancing maternal and child health services

Strengthening primary healthcare facilities is essential for the early detection and management of birth defects, including clefts. Training non-specialist health workers to provide early diagnosis, breastfeeding support, and timely referrals to specialists can reduce stigma and improve care.

Improving referral systems and continuity of care

Establishing well-coordinated referral pathways is vital to ensuring that children with clefts receive the necessary specialist services without delay. Effective coordination between community health centres, hospitals, and cleft treatment centres will ensure seamless, comprehensive care from birth through the treatment journey.

Focusing on competency-based training

To fill current gaps in care, a shift from theoretical training to competency-based approaches is needed. This should include hands-on training in breastfeeding support, growth monitoring, and infant and young child feeding practices. Additionally, healthcare workers must be equipped to recognise when and how to refer patients to specialists.

Promoting an enabling environment for breastfeeding and infant and young child feeding

Governments must address societal and cultural barriers that hinder breastfeeding and optimal infant and young child feeding practices, especially for children with clefts. Public health campaigns, policy reforms, and community-based initiatives are essential to foster an environment that supports and encourages breastfeeding and optimum nutrition for all children.

Conclusion

Smile Train’s targeted support for cleft teams and treatment centres is a crucial component in the journey towards better cleft care. However, the broader solution lies in country-level healthcare system strengthening. By advocating for these changes, we can ensure that every child with a cleft receives the comprehensive, compassionate care they deserve: from the moment they are born, throughout their treatment, and beyond.

For more information, please contact Smile Train at nutrition@smiletrain.org

References

Abida LL, Murti B & Prasetya H (2020) Meta-analysis: The effect of breast milk on child language. Journal of Maternal and Child Health, 5, 5, 579-589

Aniansson G, Svensson H, Becker M et al (2002) Otitis media and feeding with breast milk of children with cleft palate. Scandinavian Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and Hand Surgery, 36, 1, 9-15

Ceron-Zapata AM, Martinez-Delgado CM & Calderon-Higuita GE (2022) Maternal perception of breastfeeding in children with unilateral cleft lip and palate: A qualitative interpretative analysis. International Breastfeeding Journal, 17, 1, 88

Chung KY, Sorouri K, Wang L et al (2019) The impact of social stigma for children with cleft lip and/or palate in low-resource areas: A systematic review. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open, 7, 10, e2487

Gorstein J, Sullivan K, Yip R et al (1994) Issues in the assessment of nutritional status using anthropometry. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 72, 2, 273-283

IHME & Smile Train (2022) State of the world’s cleft care report. A generation lost: The devastating effect of malnutrition on children with clefts. healthdata.org

Kadir A, Mossey PA, Blencowe H et al (2017) Systematic review and meta-analysis of the birth prevalence of orofacial clefts in low- and middle-income countries. Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal, 54, 5, 571-581

Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C et al (2018) High-quality health systems in the sustainable development goals era: Time for a revolution. The Lancet Global Health, 6, 11, e1196-e1252

Victora C, Bahl R, Barris Aet al (2016) Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet, 387, 10017, 475-90

Wang D, Zhang B, Zhang Q et al (2023) Global, regional, and national burden of orofacial clefts from 1990 to 2019: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Annals of Medicine, 55, 1, 2215540

About This Article

Download & Citation

Reference this page

Barbara Delage, Joe Bwija Kasengi and Danny Loanie (2024) Feeding hope: The crucial role of nutrition in cleft care. Field Exchange 74. https://doi.org/10.71744/2gsx-se46