The impact of a Positive Deviance/Hearth intervention in Ethiopia

Frederica Smith, Epidemiologist at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Global Health Center

Takele Morka, Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability and Learning Manager at International Medical Corps (IMC)

Nazrawit Yohannes, Former Nutrition Programme Coordinator at IMC

Jennifer Majer, Senior Advisor – Monitoring and Evaluation, and Research, at IMC

Minda Sebsibe, Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability and Learning Coordinator at IMC

Sarah King, Nutritional Epidemiologist at CDC, Global Health Center

Iris Bollemeijer, Senior Nutrition Advisor at IMC

We would like to acknowledge the Ethiopia Ministry of Health for their support and for giving us permission to conduct the study. We express our sincere gratitude to the Crown Family Philanthropies and Earth Council Geneva for funding this work. We are grateful to the caregivers of all enrolled children for their participation and to all staff for their implementation of this study. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US CDC.

What we know: The Positive Deviance/Hearth (PDH) model is a behaviour change strategy that targets the nutritional wellbeing of underweight children by implementing locally developed solutions. PDH has achieved proven success in the Ethiopian context, but questions remain regarding its effectiveness beyond the implementation period.

What this adds: This study presents findings from a secondary analysis of PDH programme data from southern Ethiopia. Overall, children responded positively to the intervention, with a 46% decrease in underweight prevalence after 12 months’ follow-up. However, approximately half of the children did not return to a normal weight. Findings suggest that more intensive follow-up and/or additional nutritional interventions may be needed to reach desired nutritional outcomes, especially for younger or severely underweight children.

PDH begins by identifying families whose children are well nourished yet live in comparable socioeconomic conditions to undernourished neighbours. The practices of these ‘positive deviant families’ are then promoted, targeting families with underweight children through nutrition education and rehabilitation sessions. These families are supported to adopt culturally acceptable, affordable, and optimal nutrition practices, making these habitual behaviour changes sustainable at the household level (Nutrition Working Group Child Survival Collaborations and Resources Group (CORE), 2002). Sessions are conducted in the home (‘hearth’) of a community volunteer.

A previous intervention in Ethiopia demonstrated 8.1% and 6.3% lower prevalence of stunting and underweight, respectively, in PDH participants (aged 6-12 months) compared to those not in the programme (Kang et al, 2017). However, a systematic review revealed mixed results regarding PDH’s effectiveness and sustainability beyond the implementation period (Bisits Bullen, 2011). This article assesses the effectiveness of IMC’s PDH project by measuring changes in weight-for-age z-score (WAZ) among participating children both during and at 12 months post-implementation. WAZ was the anthropometric indicator of choice, as recommended by PDH guidance (Nutrition Working Group CORE, 2002). Our article evaluates changes in nutritional status and seeks to understand caregiver perceptions around implementing promoted practices.

Methodology

We conducted a programme evaluation involving a secondary analysis of longitudinal data from the PDH programme and focus group discussions with participating caregivers. The PDH programme was implemented from March 2021 to December 2022 in Damot Weyde and Duguna Fango woredas (districts) in the South Ethiopia Regional State. In coordination with local health facilities, IMC identified four important existing practices among mothers whose children were well nourished: 1) diversified local food preparation, 2) appropriate hygiene precautions, 3) active feeding of children, and 4) provision of healthy snacks (such as eggs and whole milk) in between household meals. These behaviours were subsequently targeted for intervention.

Study population

Underweight children (WAZ <-2) aged 6-23 months (at enrolment) were eligible for the intervention (12 consecutive days of hearth sessions) if they lived within 20 selected villages and their caregivers consented to 12 months of follow-up. During the project period, a total of 170 hearth sessions, comprising 10-12 caregivers each, were held over 12 consecutive days in both woredas. Children were included in the study if they were classified as underweight at enrolment and had monitoring data for a minimum of six months post-intervention. We included 1,138 children in the final analysis. Implausible values (WAZ ≤-6 or ≥5) were excluded. Loss to follow-up was under 10%, with only 103 children not completing the full 12-month observation period.

If children were found to be severely wasted at enrolment (mid-upper arm circumference <115 mm), they were immediately linked to an appropriate nutrition programme and excluded from the intervention. As there was no moderate wasting management in the study area, caretakers of moderately wasted children were advised to provide a diversified diet.

Data collection

Nutritional status was periodically monitored via repeated weight measurements at days 12 and 30, and months three, six, and 12 post-intervention. Children with implausible weight changes (WAZ >3 standard deviation change) since the previous measurement were excluded from the analysis.

The primary outcome was the change in WAZ status between each post-intervention time point compared to enrolment. Weight gain was included as a secondary outcome. Child nutritional status was categorised as underweight (WAZ <-2), moderate underweight (-2> WAZ ≥-3), and severe underweight (WAZ <-3) (WHO, 2023). Children were defined as “not underweight at month three” for sustained nutrition improvement if they met WAZ ≥-2 by the three-month measurement. PDH weight gain requirements define success as achieving ≥0.2 kg (12 days), ≥0.4 kg (30 days), and ≥0.9 kg (three months) post-intervention (Baik & Klaas, 2021).

A total of eight focus group discussions were conducted with 32 participant caregivers. Focus group discussions captured general recall of key messages delivered during the intervention. Each focus group discussion included four caregivers and was conducted in the Wolaytta language.

Findings

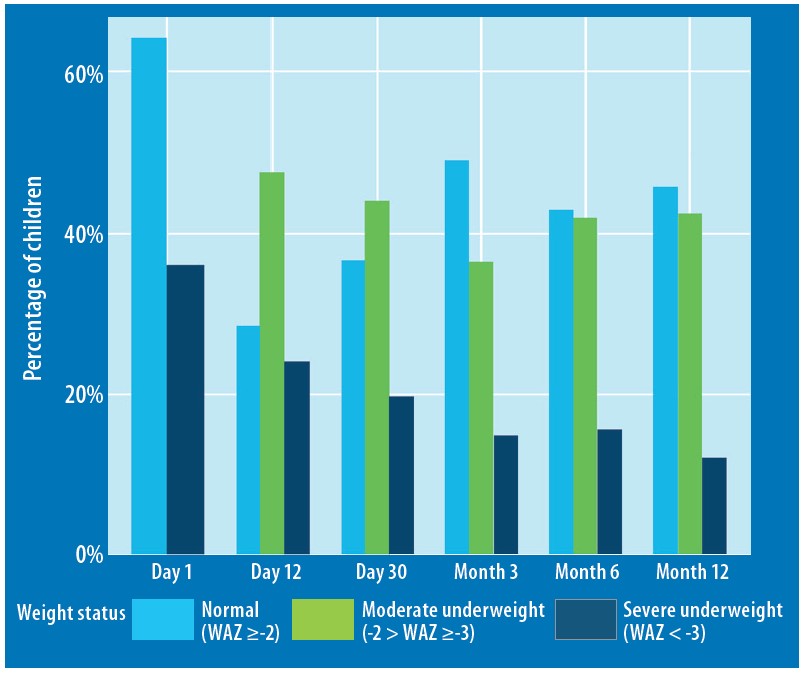

Overall, 1,138 children were included in the study (621 Duguna Fango, 517 Damot Woyde), with an average age of 13.5 months (± 4.8) at enrolment. Within three months of the intervention, 556 (49%) children met the WAZ ≥-2 criteria. Of the 1,035 children with 12 months of measurements, 472 (46%) achieved normal weight (WAZ ≥-2) by 12 months of follow-up. The prevalence of severely and moderately underweight children decreased from 36% and 64% (day 1) to 12% and 42% (month 12), respectively (Figure 1). Overall, these findings indicate that weight gain and improvement in WAZ were sustained throughout the 12-month period.

Figure 1 : Fluctuation in percentage of underweight children over 12-month follow-up period

Average overall weight gain across the 12 months was 2.55 ± 0.28 kg, with an average change in WAZ of 0.75 ± 0.36 standard deviation. At three months post-intervention, 99% of children met the 0.9 kg weight gain requirement as outlined in PDH protocols. This aligns with results from a PDH intervention in Bangladesh that observed a WAZ 0.71 standard deviation increase across its six-month follow-up period (Kim et al, 2021)

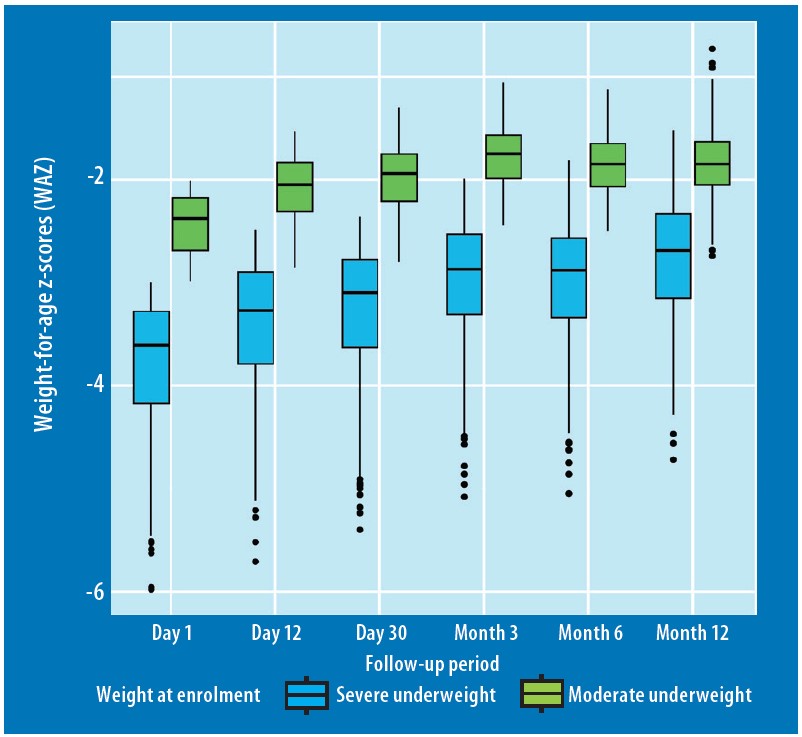

Children who were more severely underweight at enrolment remained underweight by month 12 and had a lag in catch-up growth, compared to those who began the intervention moderately underweight (Figure 2). Although the severely underweight group experienced slightly higher gains over the 12-month period, these gains were often insufficient to reach a normal weight status. This suggests that severely underweight children may require specific, targeted interventions to address their needs.

Recent research highlights that a WAZ <-3 identifies children at higher risk of death, particularly when combined with other anthropometric criteria (Khara et al, 2023). This has become a key targeting criterion in the 2023 World Health Organization (WHO) guideline on the prevention and management of wasting (WHO, 2023). While local food interventions may provide sustained nutritional benefits for moderately underweight children, our findings suggest that more intensive nutritional support is likely to be necessary for those most at risk.

Figure 2: Weight-for-age z-score (WAZ) changes disaggregated by nutrition status at enrolment

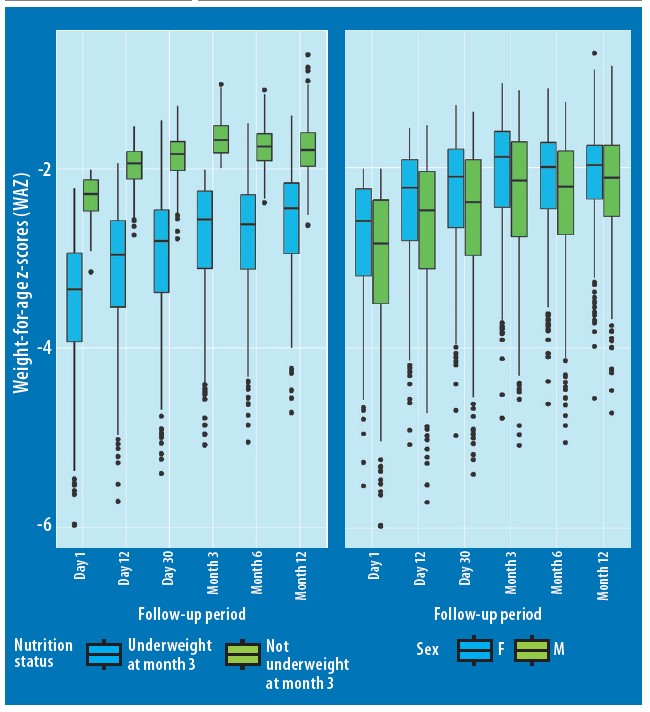

In Bangladesh, children who were underweight at month three did not catch up to their non-underweight counterparts by month six. In this Ethiopian setting, the average weight gain between the two groups remained similar across all observation points. However, between months three and six and months six and 12, the “underweight at month three” group experienced greater weight gain and total WAZ change compared to the “not underweight at month three” group (Figure 3). Underweight children at month three may therefore have had more capacity for weight gain, whilst the other group may have already achieved their optimal weights. Children who were classified as “not underweight at month three” generally started the intervention with a higher average WAZ.

Variation across sexes and age groups

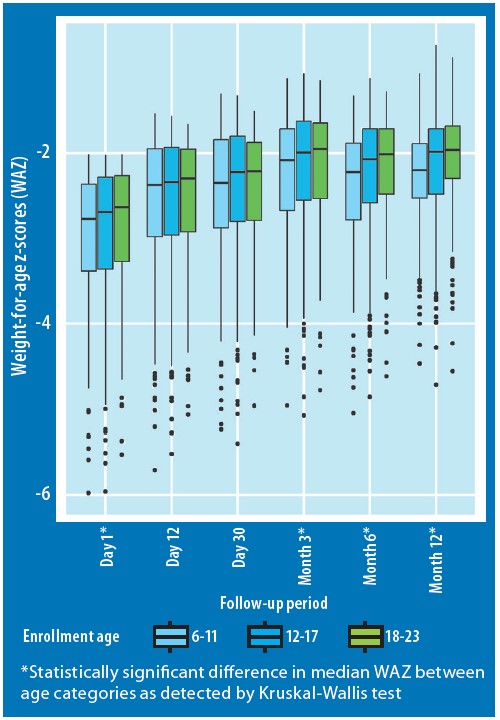

Male children consistently had significantly lower WAZ than females at both enrolment and throughout follow-up (Figure 3). This is in line with the broader literature (Thurstans et al, 2020). There were statistically significant differences in median WAZ between age categories at day one, month three, month six, and month 12 (Figure 4). Children aged 6-11 months at enrolment had the lowest WAZ throughout the follow-up period, followed by children aged 12-17 months. Child age at enrolment therefore appeared to impact nutrition outcomes. PDH should more closely examine differences in feeding patterns across age groups and complementary foods in this setting. At 6-11 months, children are introduced to complementary feeding and are consequently more vulnerable to foodborne illnesses and/or inadequate feeding.

Figure 3: Differences in weight-for-age z-score (WAZ) disaggregated by nutrition status and sex

Figure 4: Participant weight-for-age z-score (WAZ) disaggregated by age category

By month six, all age groups experienced a rise in the prevalence of underweight (compared to month three), with the two eldest age categories returning to their month three status by month 12. While seasonality and other contextual factors may have had an effect, this suggests that more intensive reinforcement of PDH concepts at each follow-up period may yield a greater response. This could include additional nutritional counselling and education about complementary feeding to reinforce PDH concepts. Previous studies have demonstrated a sustained impact on improving WAZ when employing a phone-based intervention (Young et al, 2021). This was likely due to participants receiving twice the number of follow-up sessions compared to the traditional PDH group.

Qualitative and contextual findings

A full breakdown of the qualitative results is beyond the scope of this article. However, caregivers across both of the response groups expressed similar challenges and successes related to food affordability and availability, healthcare-seeking practices, complementary feeding, and overall programme perceptions. Participants in many of the focus group discussions cited economic limitations. Not all families could afford or access the recommended food types, leading to adaptations based on available resources.

The region experienced severe drought conditions which worsened malnutrition in 2022 compared to 2021. Seven zones faced water shortages, with water availability at critical levels. This may have contributed to only 46% of children reaching normal weight and makes the case for providing additional support in contexts of drought and severe food insecurity. Notably, caregivers expressed that previous timely seed allocations had enabled them to implement ideas from the PDH sessions by growing food in home gardens.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of our study is the fact that we monitored nutritional outcomes over a 12-month period, enabling us to measure the sustained impact of the intervention. We also showed programme success in a food-insecure area, which has been previously cited as a challenge by a multi-country PDH programme evaluation (Baik, 2019).

We did not include controls in our study design and therefore could not adjust for confounding variables or compare growth outcomes to children not enrolled in the intervention. At baseline, we did not collect covariates, such as height, breastfeeding history, household food security status, and recent treatment for wasting. This would have allowed for a more robust analysis. Consequently, we were unable to assess the impact of wasting and stunting on a child’s response. Since WAZ reflects both conditions, it is possible that the response was influenced by their presence. We recommend the collection of these variables in future PDH programming to better inform the conclusions drawn from PDH programme evaluations.

Conclusions

While there were improvements in child underweight status, approximately half of the children did not return to a normal weight-for-age during the intervention and follow-up period. Some families could not afford or access the recommended food types. Our results suggest that more intensive follow-up and/or additional nutritional interventions may be needed to reach desired nutritional outcomes, especially for younger children or severely underweight children. The use of interventions that incorporate existing community-based solutions have the potential to significantly reduce child undernutrition. Additional interventions that address economic limitations could further benefit families. Our findings provide a baseline understanding of the challenges and successes of PDH in our specific context and can help with future implementation in the community.

These results are timely given the new WHO guideline on the prevention and management of wasting (WHO, 2023), which recommends increasing undernourished children’s access to local nutrient-dense diets and implementing interventions, such as PDH, for infants and children with moderate wasting.

For more information, please contact Frederica Smith at yfn0@cdc.gov

References

Baik D (2019) World Vision’s positive deviance/hearth programme: multi-country experiences. Field Exchange 60. https://www.ennonline.net/fex/60/worldvisionsprogramme

Baik D and Klaas N (2021) World Vision’s training of facilitators for Positive Deviance Hearth (3rd ed.). wvi.org

Bisits Bullen PA (2011) The positive deviance/hearth approach to reducing child malnutrition: systematic review. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 16, 11, 1354-1366.

Kang Y, Kim S, Sinamo S et al (2017) Effectiveness of a community-based nutrition programme to improve child growth in rural Ethiopia: A cluster randomized trial. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13, 1

Khara T, Myatt M, Sadler K et al (2023) Anthropometric criteria for best-identifying children at high risk of mortality: a pooled analysis of twelve cohorts. Public Health Nutrition 26, 4, 1-17

Kim Y, Biswas JP, Hossain MI et al (2021) Age differences in the impact of a Positive Deviance/Hearth programme on the nutritional status of children in rural Bangladesh. Public Health Nutrition, 24, 16, 5514-5523

Nutrition Working Group, CORE (2002) Positive Deviance / Hearth: A Resource Guide for Sustainably Rehabilitating Malnourished Children.

Thurstans S, Opondo C, Seal A et al (2020) Boys are more likely to be undernourished than girls: A systematic review and meta-analysis of sex differences in undernutrition. BMJ Glob Health, 5, 12

WHO (2023) WHO guideline on the prevention and management of wasting and nutritional oedema (acute malnutrition) in infants and children under 5 years. who.int

Young MF, Baik D, Reinsma K et al (2021) Evaluation of mobile phone-based Positive Deviance/Hearth child undernutrition program in Cambodia. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 17, 4, e13224

About This Article

Jump to section

Download & Citation

Reference this page

Frederica Smith, Takele Morka, Nazrawit Yohannes, Jennifer Majer, Minda Sebsibe, Sarah King and Iris Bollemeijer (2024). The impact of a Positive Deviance/Hearth intervention in Ethiopia. Field Exchange 74. https://doi.org/10.71744/6hj9-0n55