How Inter-Cluster/Sector Collaboration (ICSC) can enhance programming in South Sudan

Ruth Situma Chief of Nutrition, Former Cluster Coordinator at UNICEF South Sudan

Frederic Patigny Former WASH Cluster Coordinator at UNICEF South Sudan

Maleng Ayok Amet Roving Sub-National Nutrition Cluster Co-Coordinator at South Sudan Nutrition Cluster

Marie Cusick Communications Consultant at Global Nutrition Cluster

Rachel Lozano Former ICSC Consultant at Global Nutrition Cluster

What we know: Siloed approaches to humanitarian emergencies rarely achieve the required results and often leave out affected and vulnerable populations. Coordinated, holistic approaches utilise the expertise and perspectives of various sectors and affected communities. It is recommended to apply such approaches in order to respond more adequately to emergencies.

What this adds: We outline the Inter-Cluster/Sector Collaboration (ICSC) approach, its purpose, successes, and challenges, as applied in the South Sudanese context. Observational data indicates that the ICSC approach positively impacted nutrition outcomes and their drivers, with qualitative findings showcasing the necessity of appropriate coordination and collaboration between actors.

In 2022, the Nutrition, Water, Sanitation & Hygiene (WASH), Food Security, and Health sectors established ICSC to bolster collaboration in humanitarian response. ICSC is a holistic approach, centred on relevant clusters/sectors coming together to share information, actively plan, and work on joint actions. ICSC reinforces the work of the Inter-Cluster Coordination Group (ICCG). ICSC aims to reduce access barriers (such as transportation costs), time spent in service provision, and exposure to potential risks. ICSC is stronger than the well-known ‘multi-sectoral’ approach, where different sectors co-exist in a similar area but do not necessary target the same communities or health facilities. ICSC began in 2019 and was fully developed by 2022.

Depending on the context and needs of the affected populations, fewer or more clusters (such as Protection, Shelter, Education) may collaborate to provide the optimum response. Participation is driven by the identified common objective that led to the creation of the group, which is often the initiative of one cluster.

Multiple Lancet series (2008; 2013; 2021) evidence the effectiveness of integrated nutrition-sensitive and nutrition-specific interventions for reducing maternal and child malnutrition. Even when implemented at scale, nutrition-specific interventions alone can only reduce malnutrition by 20%. The remaining 80% needs to be addressed through nutrition-sensitive interventions (Bhutta et al, 2013), reinforcing the importance of such a holistic approach.

The Greater Tonj

The Greater Tonj consists of three counties (Tonj East, Tonj North, and Tonj South) in Warrap State, South Sudan. The area has repeatedly faced challenges to food and nutrition security, stemming largely from crippling socioeconomic and demographic conditions. In 2016, food insecurity hit a historic high. However, wasting prevalence had already been above the 15% emergency threshold for decades (World Food Programme (WFP), 2016). A 2017 Integrated Nutrition and Food Security Causal Analysis noted that the predictable seasonal pattern of food insecurity and associated nutrition indicators had been overshadowed by non-food-related causes. These included poor WASH-associated morbidity, poor health-seeking behaviours, and poor infant and young child feeding practices (WFP et al, 2018).

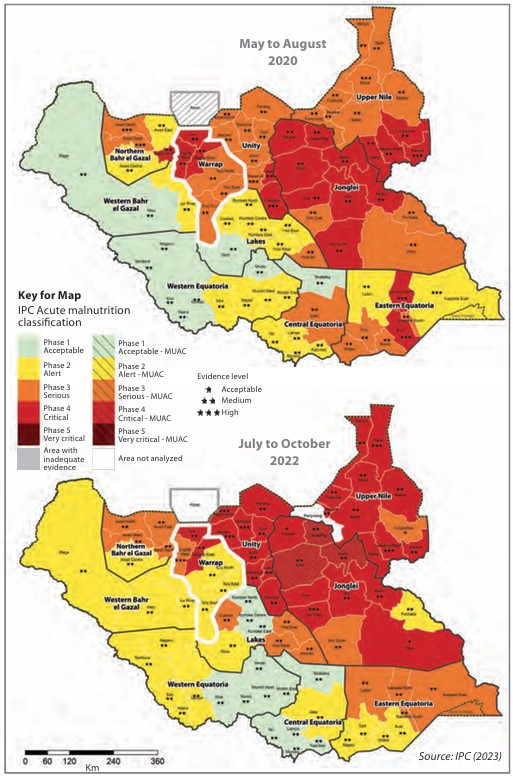

More recent analysis shows that the main drivers of food insecurity in South Sudan include conflict and insecurity, climatic shocks (like floods and dry spells), high food prices, animal disease outbreaks, crop pests and diseases, and reduced household income (IPC, 2023). Due to this combination of factors, it was realised that the humanitarian response requires a holistic, multi-sectoral approach.

A holistic approach

Building on the existing emergency response, an ICSC approach began in South Sudan in late 2020. By agreeing to work together, the Nutrition, WASH, Health, and Food Security and Livelihood clusters first needed to identify areas where they could intervene jointly. Areas designated as Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) acute food insecurity level 4 (“emergency”) and 5 (“famine”), coupled with high WASH and health vulnerabilities, were prioritised for immediate response, based on 2020 data. This was complemented at the local level by implementing partners, authorities, and communities who confirmed those areas with the highest needs (wasting prevalence, WASH conditions, diarrhoea cases, and others). As a result, 17 counties were selected for the joint interventions, including Tonj North, Tonj East, and Tonj South.

The four clusters, and the Gender-Based Violence in Emergencies sub-cluster, then defined a multi-sectoral package of interventions to address the interconnected drivers of malnutrition (Table 1).

Table 1: The agreed package per cluster

| Cluster | Package |

| Nutrition |

|

| WASH |

|

| Food Security and Livelihood |

|

| Health |

|

| Gender-Based Violence in Emergencies |

|

The clusters brought partners together before projects commenced to align each actor on the objectives and types of intervention required. Partners from different sectors were selected to deliver the ICSC package, depending on their respective expertise. Based on capacity and funding availability, some partners were able to deliver the whole package, while others needed to be part of a consortium with other organisations. Packages were delivered at health facility and community levels within agreed catchment areas.

In early 2023, after almost two years of joint implementation, the WASH and Nutrition clusters organised a joint field visit to the three Tonj counties. The visit collected qualitative information through 28 key informants (24 community members; four government members) and six focus groups. Exchanges with 12 mothers took place at the four new water points or at the health facility level. There was no predetermined selection methodology for those interviewed. This lack of robust sampling methodology limits generalisability and the strength of the conclusions that can be drawn from the qualitative data, but it does complement the available quantitative information. Quantitative data was collected by partners directly at health facilities or from existing surveys and gathered through the yearly Humanitarian Needs Overview and Humanitarian Response Plan process.

Findings

Nutrition situation improved

According to IPC data on wasting levels (Figure 1) we observed an improvement in the nutrition situation in the Tonj counties where the ICSC approach was delivered for two years. Wasting prevalence in the three Tonj counties (collected in October 2022) decreased below emergency levels to 9.6%. This had not been seen since 2015.

Figure 1: Acute malnutrition (wasting) in South Sudan (2020-2022)

Source: IPC (2023)

Drivers of malnutrition improved

WASH severity levels were compared between 2021 and 2022. These levels were determined by access to sufficient water for domestic usage, an improved source of water, and a basic sanitation facility. Severity dropped from ‘high’ concern in all three Tonj counties to “medium”, aligning with the improvement in IPC acute malnutrition findings. There are several reasons for this reduction.

Notably, 33 out of 44 (75%) health and nutrition sites now have improved access to safe and clean water provided by WASH partners. This benefits 80% of the targeted communities. New boreholes were also built, others were maintained, and additional sanitation facilities were upgraded. All cases of severe wasting admitted for treatment (around 8,000 individuals), received a WASH kit (including buckets, chlorine tablets, soap, and other items), in addition to standard medical and nutritional care.

A reduction in diarrhoeal disease cases was observed in areas where the ICSC package of interventions was implemented, from 32,516 cases in 2021 to 28,191 cases in 2022 (World Health Organization & IDSR, 2022). No reductions were observed in areas that did not receive ICSC interventions. This information was corroborated by the local authorities.

“Because of integrating WASH into health and nutrition, we have seen a reduction in diarrhoea diseases among children in Warrap State” – Director General, State Ministry of Health

All interviewed women and water committee chairs also reported improvements in child health, with fewer diarrhoea episodes and improved nutritional status. Those whose children had been admitted to health and nutrition facilities for wasting (5 out of 12 women interviewed) shared that they had had no relapse after the treatment.

“It is so rewarding for us as mothers to see our children growing healthier, better nourished, with less diarrhoea, and cleaner” – Mother in Alor Village, Tonj East County

Focus group discussions indicated that gender-based violence risk reduced in conjunction with decreased distances between households and water points. This was supported by the figures reported in Tonj South for both male and female outpatient and inpatient department consultations (86 cases in 2021; 49 cases in 2022).

Women reported that access to water and hygiene items made them feel more self-confident and provided a sense of dignity. Access to safe and clean water reduced tension between communities. This was repeated by people at the four water points and six nutrition sites visited. When women accessed a remote water point, they were not always made welcome by a neighbouring community. This has now been mitigated as women do not have to travel between communities for water.

Successes

By prioritising a holistic approach to addressing the drivers of malnutrition, based on joint assessments, all actors felt they had an important role to play and there was cohesion among partners and government ministries. All parties reported collegial working relationships, with continuous exchanges of information and ideas on how to best serve the communities. Since inception, government staff were included in all programme meetings to ensure accountability and sustainability. The government provided an enabling environment for partners throughout, ensuring both programme security and smooth delivery.

“As WASH partners, we are guided by health and nutrition partners on where to provide water. We usually use health and nutrition assessments to decide where to drill boreholes in the communities” – WASH partner

Across sectors, community frontline workers (community nutrition volunteers, Boma health workers, and hygiene promoters) played a significant role in delivering coherent social behaviour change communication messages to communities. For instance, the 12 women/mothers interviewed were aware of the need to use safe and clean water for food preparation, drinking, and domestic use. They also knew the importance of hand washing with soap at critical moments, which is uncommon in other parts of South Sudan due to cultural norms.

Community feedback mechanisms (exit interviews, community nutrition volunteer home visits, hotlines, and mother-to-mother support groups) supported the implementation of the ICSC approach. For example, community feedback led to the inclusion of a water yard at a nutrition site, which was then connected to two water kiosks supplying nearby communities. This system (managed by the nutrition site) guaranteed sustainable access to safe and clean water.

To strengthen women’s empowerment, village savings and loans associations were implemented and the chairing of water committees by women was favoured. With improved access to safe and clean water, mother support groups successfully maintained kitchen gardens in communities, health, and nutrition sites. These interventions were supported by the ICSC approach as services were delivered by a partner at the same time, in the same place, and to the same beneficiaries.

Challenges

Discontinuity of the ICSC package, due to unforeseen constraints, was an issue. For example, WASH supplies were not available in some nutrition sites due to transport issues (floods) and some nutrition sites had to close due to insecurity. The lack of resources also limited the provision of the comprehensive package to communities. For example, limited funding to Health (through the Health Pooled Fund) and Food Security and Livelihood Cluster partners reduced health services, food rations, and the availability of seeds. In addition, unharmonised pay and incentives for staff and frontline workers led to resignations, disrupting some of the work’s progress.

Despite strong engagement, it was often difficult to agree and organise joint visits, due to competing priorities and work schedules. This resulted in only one joint visit between WASH and Nutrition Clusters at the end of project implementation. More regular joint visits, including all clusters, would have helped to ensure that the package was fully delivered and adjusted in real time, as needed.

Lessons learned and recommendations

There are several themes that can be extracted from the lessons learned in Greater Tonj. Clear communication and regular joint planning meetings between actors (government, humanitarian, and development) must be established, alongside effective and accountable collaboration with communities. Ideally, collaboration should begin before an emergency hits and needs should be anticipated before an ICSC project is implemented, to avoid significant delays in project rollout. Preparedness is key.

Utilising joint monitoring indicators is also important as these can better reflect the outcomes of the joint interventions, in addition to sectoral indicators. We recommend harmonising the incentives, services, and messaging provided by all frontline workers to support this.

To ensure the sustainability of recent gains in Greater Tonj, we advocate for continued investment in an integrated response and a scale-up of prevention efforts. This includes integrating nutrition services as part of the County Health Department's priority for investment and the gradual absorption of community nutrition volunteers into the Boma Health Initiative. Under health authority management, water supply systems at the health and nutrition facilities should be upgraded to supply neighbouring communities. Food Security and Livelihood partner activities, such as local seed multiplication and strengthening community livestock and poultry production capacity, as well as kitchen gardens, can generate household income and support other sector initiatives.

Conclusion

Our findings illustrate how the ICSC approach can be used to address the interconnected drivers of malnutrition. In Greater Tonj in South Sudan, ICSC had multiple knock-on effects. The decreased distance between households and water points reduced the risk of gender-based violence. Access to safe and clean water reduced tension between communities. Access to hygiene items made women feel more self-confident and gave them a sense of dignity. We noted corresponding improvements in child health and nutritional status. ICSC is currently being implemented within humanitarian responses elsewhere in South Sudan and globally, as a holistic approach to addressing the multiple factors that drive malnutrition rates.

For more information, please contact the Global Nutrition Cluster at gnc@unicef.org

References

Bhutta Z, Das J, Rizvi A et al (2013) Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: What can be done and at what cost? The Lancet, 382, 9890, 452-477

IPC (2023) South Sudan: Acute malnutrition situation July-October 2022 and projections for November 2022-February 2023 and March-June 2023. ipcinfo.org

The Lancet (2008) Maternal and child undernutrition. thelancet.com

The Lancet (2013) Maternal and child nutrition. thelancet.com

The Lancet (2021) Maternal and child undernutrition progress. thelancet.com

World Health Organization & IDSR (2022) South Sudan weekly disease surveillance bulletin 2022. afro.who.int

WFP (2016) WFP South Sudan Food Security and Nutrition Monitoring Report (FSNMS) - Round 18, July 2016. reliefweb.int

WFP, Ministry of Health, UNICEF, UN Food and Agriculture Organization, World Health Organization, FEWSNET, Save the Children & Action Against Hunger (2018) Integrated food and nutrition security causal analysis: A WFP led collaborative study that investigated factors underlying persistent acute malnutrition and food insecurity in Warrap and Northern Bahr el Ghazal.

About This Article

Download & Citation

Reference this page

Ruth Situma, Frederic Patigny, Maleng Ayok Amet, Marie Cusick and Rachel Lozano (2024). How Inter-Cluster/Sector Collaboration (ICSC) can enhance programming in South Sudan. Field Exchange 74. https://doi.org/10.71744/1wdw-xm03