Weekly iron and folic acid supplementation and nutrition education for adolescent girls in Africa and Asia

This is a summary of a Field Exchange field article that was included in issue 66. The original article was authored by Anjali Bhardwaj, Lucy Murage, Shibani Sharma, Dhian Dipo, Christine Makena, Marion Roche and Mandana Arabi

Anjali Bhardwaj is the Regional Manager for Adolescents and Women’s Health and Nutrition for Asia at Nutrition International.

Lucy Murage is the Regional Advisor for Adolescents and Women’s Health and Nutrition for Africa at Nutrition International.

Shibani Sharma is a Junior Technical Officer for the Adolescents and Women’s Health and Nutrition programme at Nutrition International’s headquarters in Ottawa.

Dhian Dipo is Director of Public Health Nutrition at the Directorate General of Public Health, Ministry of Health, Republic of Indonesia.

Christine Makena is a Senior Programme Officer in charge of the Kenya Adolescent Health and Nutrition programme at Nutrition International, Kenya Office.

Marion Roche is the Senior Technical Advisor for Adolescents and Women’s Health and Nutrition at Nutrition International.

Mandana Arabi is Vice President and Chief Technical Advisor for Global Technical Services at Nutrition International headquarters.

Nutrition International has supported governments to develop and implement weekly iron and folic acid (IFA) supplementation and nutrition education to reduce anaemia in six high-risk countries since 2015.

- Despite regional supply chain challenges and COVID-19 pandemic-related complications, IFA supplementation coverage increased in all countries.

- A paucity of data on adolescent outcomes continues to restrict the design, implementation and monitoring of adolescent nutrition programmes.

- Although school-based delivery models are effective at the population level, reaching out-of-school adolescents remains a significant challenge. Governments should prioritise community-based approaches to reach this isolated and often more vulnerable group.

Background

Since 2015, Nutrition International (NI) has worked with national and subnational governments in six African and Asian countries (India, Indonesia, Kenya, Senegal, Ethiopia and Tanzania) to implement adolescent nutrition programmes under the ‘Right Start’ initiative (2015-2020). Programmes are based on World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations and include weekly iron and folic acid (IFA) supplementation (WIFAS) and nutrition education to reduce anaemia.

Programme description

In each country, NI consulted with the government to develop context-specific strategies for WIFAS and nutrition education. They also collaborated with the government and non-governmental organisations to deliver these programmes.

Across countries, programme development and implementation incorporated:

- Delivery platforms: In most countries, government-funded schools were the preferred delivery platforms since they allowed access to the largest groups of adolescents. However, in some countries, including India and Ethiopia, community-based approaches were incorporated to reach out-of-school adolescent girls.

- IFA supplies: Adolescent girls require WIFAS using a distinct formulation. Although NI worked with UNICEF to ensure that appropriate IFA supplements became available in the UNICEF supply catalogue in 2019, they are still not part of the WHO Essential Medicine List (EML). This means that governments have not been able to purchase them and NI has supported the supply chain for the government-endorsed product. NI has also provided financial, technical and operational support to governments to improve the forecasting, procurement and supply capacity of health staff, strengthening supply chain management and providing training for teachers, health staff and other district officials. NI has also supported the harmonisation of joint forecasting and procurement for both maternal and adolescent nutrition programmes.

- Nutrition education: Adolescent nutrition programmes have included robust evidence-based behaviour change interventions (BCI). These were informed by formative research with adolescents, parents, health staff, teachers, community influencers and religious leaders.

- Gender mainstreaming: NI recognises the need for a gender-responsive approach to adolescent nutrition programmes. Thus, although adolescent girls were prioritised for WIFAS, both girls and boys have received nutrition education. Men’s buy-in to the programme was also crucial to reaching adolescent girls and achieving scale-up.

- Service providers: The training and capacity-building of service providers from health and education departments was undertaken at scale. Programme managers from the Ministries of Health, Education and Agriculture were trained as trainers. Trainings were then cascaded to frontline health workers, community health volunteers, teachers and peer educators. In most contexts, teachers were responsible for managing programmes within schools. Health workers collaborated with teachers to connect schools to health facilities and ensure that IFA supplies reached schools. Since all WIFAS programmes were government-led, the duties of teachers and health workers were incorporated into their workload in government schools.

- Generating evidence and measuring progress: When possible, the coverage of WIFAS programmes was reported through the governments’ Health Management Information System (HMIS). When the HMIS did not include IFA supplementation indicators (such as in most African countries), parallel paper-based systems were used. Data was recorded by teachers and consolidated by NI programme managers.

NI also conducted quantitative and qualitative surveys including baseline, midline and endline assessments. Within NI’s global Nutrition Intervention Monitoring System, a set of uniform survey tools and data collection methodologies was developed. These modules were easily adaptable by context and were implemented in all countries since 2017 with the exception of India where a reliable HMIS system was already in place.

- Programme adaptations to the COVID-19 pandemic: After school closures disrupted the WIFAS programmes, NI advocated for and supported the delivery of WIFAS through community outreach. Adaptations included providing additional IFA tablets to cover the period of school closures, delivering IFA tablets to homes or sending them with remote school curriculum packages and adapting digital platforms to continue nutrition education, data collection and monitoring.

Results/outcomes

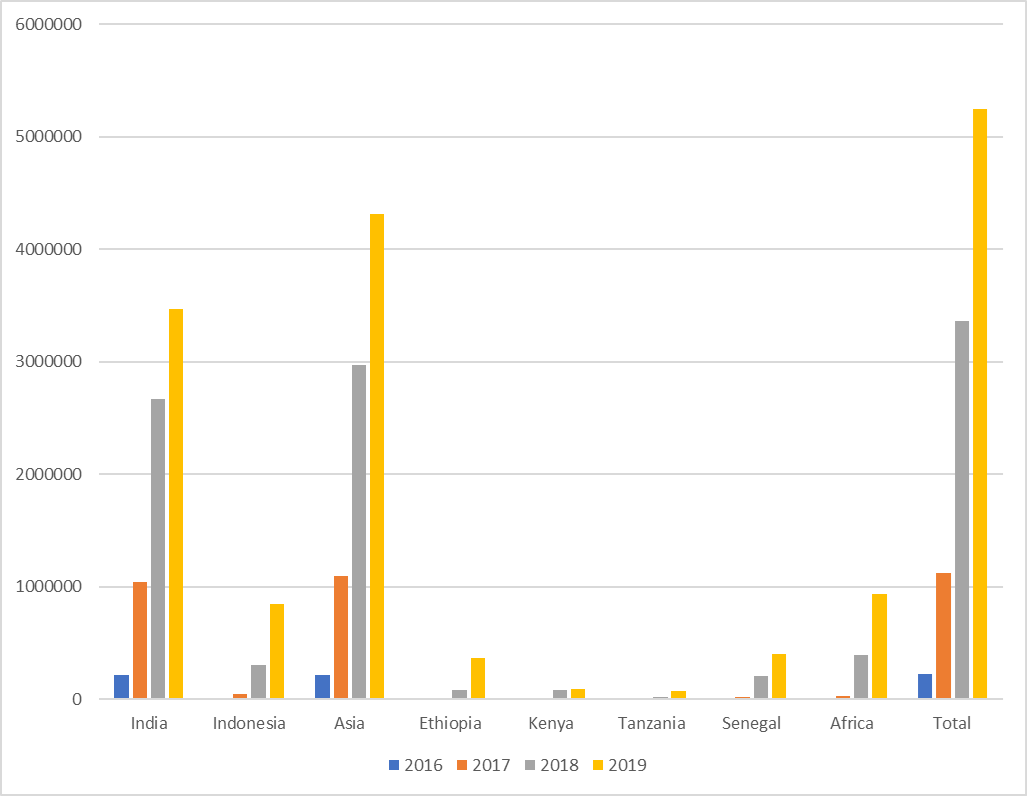

- The number of adolescent girls reached with WIFAS and nutrition education increased across all countries, with greater success in Asian countries (Figure 1).

- In total, approximately 1.2 million cases of anaemia have been averted.

- NI’s programme evaluation survey results show increased receipt of, and adherence to, WIFAS.

- Nearly 3.7 million adolescents, including almost one million boys, were reached with nutrition education over two years.

- More than 195,000 frontline workers were trained to deliver and support the implementation of the adolescent nutrition programme.

Figure 1: Additional1 adolescent girls who consumed the recommended weekly IFA supplements2 by country from 2016 to 2019

Successes, challenges and lessons learned

The WIFAS programmes were successful in supporting governments to create enabling environments and to develop capacity for delivering adolescent nutrition programmes. Successes, challenges and lessons learned during programme development and implementation include:

- Lack of adolescent specific data: In many countries, adolescent-specific indicators are lacking in HMIS. To address this, NI conducted formative research at the beginning of each programme to inform context-specific programme design.

- IFA supplies: IFA shortages are common in many low- and middle-income countries and regular stock-outs and irregular and unequal distribution of IFA supplements pose immense challenges. NI provided technical assistance and operational support to governments which increased their responsibility for procuring IFA supplements during the scale-up period.

- COVID-19 related challenges: Adolescent nutrition programming consistently evolved during the COVID-19 pandemic, using digital technology and virtual platforms to continue nutrition education. After an initial drop, the coverage of WIFAS increased as more girls were reached via community platforms.

- Adolescent participation: Adolescents led key activities and provided crucial support to promote the acceptance and continuation of NI’s programmes. Examples of adolescents’ engagement included acting as ‘motivator’ girls in Ethiopia, designing BCI campaign slogans in Kenya and participating in a content creation workshop in Indonesia.

- Reaching out-of-school girls: Coverage among out-of-school adolescent girls remains low. National governments need to make targeted investments to reach them with WIFAS and nutrition education. Lessons learned from India’s experience in reaching both in- and out-of-school-adolescent-girls show that designating pre-existing, functional community-based platforms could be effective in other countries.

- Advancements in adolescent nutrition programming and training: NI’s efforts contributed to IFA supplements becoming available in their recommended dosages for weekly supplementation. NI worked with academic researchers to understand the efficacy of WIFAS for the prevention of neural tube defects, making IFA supplements eligible for consideration for the EML for anaemia and neural tube defects. NI is leading the development of technical resources for the capacity-building of programme staff, partners and interested stakeholders. These include the Adolescent Nutrition and Anaemia Online Course3, frequently asked questions for WIFAS4 and tools to support gender mainstreaming.

Conclusion

NI’s experiences demonstrate the successful establishment and scale-up of WIFAS across countries in Asia and Africa. Moving forward, the development of more resilient and adaptable government-supported programmes that feature active engagement and participation from adolescents and their communities is needed to improve the delivery and uptake of adolescent nutrition programmes.

For more information, please contact Anjali Bhardwaj at abhardwaj@nutritionintl.org.