Affordable and nutritious child feeding in Nigeria: Applying Cost of the Diet modelling

This is a summary of a Field Exchange field article that was included in issue 69. The original article was authored by Md Masud Rana, Gideon Luper Abako, Boluwatito Samuel and Alabi Oluyomi.

Md Masud Rana is a Nutrition Advisor at Save the Children, UK.

Gideon Luper Abako is a Nutrition Innovation Coordinator at Save the Children, Nigeria.

Boluwatito Samuel is a Nutrition Specialist at Save the Children, Nigeria.

Alabi Oluyomi is an Assessment and Research Manager at Save the Children, Nigeria.

Key Messages:

- This article explores a ‘Cost of the Diet (CotD)’ assessment, conducted in Nigeria in 2022, which identified the cheapest approaches to meet all the nutritional requirements of children aged 6-23 months throughout the year, from locally available and culturally acceptable food items.

- Markets in the assessment area had a diverse range of food items that could fulfil all major macro-and micro-nutrient requirements. However, even the lowest-cost diet meeting the nutritional requirements was expensive compared to the standard income of the target population.

- This study demonstrates that CotD modelling can be used to develop tools, such as a recipe booklet, to support maternal and child nutrition, as well as to understand the extent to which economic constraints may impact diets.

Background

To improve maternal and child nutritional status in Nigeria the Federal Government implemented the Accelerating Nutrition Results in Nigeria (ANRiN) project across 12 states with the highest burden of malnutrition in the country. The project focused on increasing access to, and utilisation of, Nigeria’s Basic Package of Nutrition Services, which includes the promotion of infant and young child feeding practices through social and behaviour change communication activities. However, evidence suggests that economic constraints can limit the effectiveness and sustainability of such initiatives if nutritious foods are unavailable or are too costly.

In 2022 we conducted a Cost of the Diet (CotD) assessment in Oya, one of the states included in the ANRiN project. The study aimed to answer the following questions:

- What is the minimum cost of a nutritionally adequate and culturally acceptable diet for a typical household in Ogo Oluwa and Afijio Local Government Areas of Oyo state?

- What locally available foods are inexpensive sources of essential nutrients and can be promoted through programme interventions?

Methods

The CotD analysis used primary data and internal databases to estimate the cost, quantity and combination of local foods needed to provide target individuals and households with a diet that met average energy needs and recommended intakes of protein, fat and micronutrients. Primary data (Box 1) were collected from 10 villages from January to February 2022).

Box 1: Primary data collection

- Market surveys were used to obtain the prices and weights of food items found in the assessment area across various seasons.

- Food frequency questionnaires were administered to eight women (with children under two years of age, and who were also the primary food preparers in the household), to assess the consumption frequency (per week) of all food items contained in the market survey questionnaire.

- Focus group discussions were conducted with the women to obtain insights into typical food consumption habits, cultural practices and food taboos.

The analysis estimated the following:

- A lowest-cost diet that only met recommended average energy requirements (energy only (EO) diet).

- A lowest-cost diet that met specifications for energy, protein, fat and micronutrients but that did not consider typical dietary habits (minimum-cost nutritious (NUT) diet).

- A nutritious diet, calculated by applying constraints at the time of analysis to include the staple foods and to exclude taboo foods (staple-adjusted nutritious (SNUT) diet).

- A lowest-cost diet that met specifications for energy, protein, fat and micronutrients and that considered typical dietary habits and cultural acceptability (food habit nutritious (FHAB) diet).

For each wealth group (poor and affluent households), income and non-food expenditure data were entered into the CotD software to determine how affordable each diet was.

Limitations

The software:

- assumes that the average household comprises a man, a breastfeeding mother, and three children, including a child aged 12-23 months;

- does not consider nutrient requirements for convalescing individuals;

- assumes that this particular diet will be consumed by each family member on a daily basis and at every meal;

- fails to consider the requirements for vitamin D, iodine, and essential amino and fatty acids; and

- does not consider inter-household food distribution.

Findings

The cost of meeting the nutritional requirements of breastfeeding women was highest (27% of household spend), followed by meeting the nutritional requirements of men (25%), of children aged 11-12 (24%), of children aged nine to 10 (19%) and of children aged 12-23 months (5%).

Overall, markets in the assessment area had a diverse range of food items that could fulfil all major macro- and micro-nutrient requirements. While this analysis did not identify any limiting nutrients in the assessment zone, calcium and iron were found to be the most difficult to obtain. No specific food taboos were observed for children.

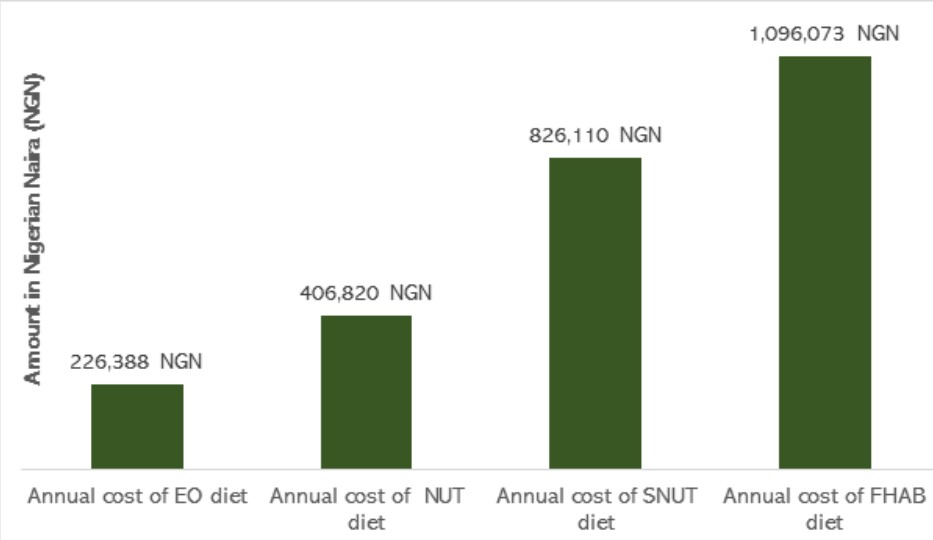

Figure 1: The annual cost of various diet types for a standard household with five members

Abbreviations: EO - energy only diet; FHAB - food habit nutritious diet; NUT - minimum-cost nutritious diet; SNUT - staple-adjusted nutritious diet; NGN - Nigerian Naira.

Although the FHAB diet was 2.7 times more expensive than the NUT diet (Figure 1), food items selected for the FHAB diet were still some of the cheapest options available in the markets. Nevertheless, poor households in the study area were unable to afford both nutritious food and non-food items. Poor households faced a shortfall of NGN 53,771 (USD 120), NGN 475,500 (USD 1,055) and NGN 745,463 (USD 1,650) in regard to being able to afford a NUT, SNUT and FHAB diet, respectively. Conversely, wealthier households with an income in line with the national annual minimum wage could afford both the FHAB diet and non-food expenditure, with a predicted surplus of NGN 241,515 (USD 535).

Nutritious diet ‘what if’ modelling

The CotD assessment found that the cost of a nutritious diet can be significantly reduced by incorporating underutilised nutritious, but cheap or free, food into the local diet: for example, consuming moringa leaves more frequently or replacing yam flour or grated cassava with sweet potatoes.

If a typical poor household adopted both of these practices, the annual cost of the FHAB diet for the entire family would be reduced by 42%. The cost of a nutritious diet for breastfeeding mothers and children under two years of age could be reduced by up to 40% and 36%, respectively.

Development of recipes

To improve child feeding practices and to promote affordable complementary food, the ANRiN project team developed a recipe book containing 20 low-cost, nutritious recipes based on food items identified by the CotD analysis, considering the availability, price and nutrient content of all food items, as well as food preferences and dietary practices.

Conclusion

Overall, markets in the study area had a diverse range of food items that could fulfil all major macro- and micro-nutrient requirements. These results appear to justify the aim of the ANRiN project to enhance children’s nutritional status by reducing affordability gaps. This study demonstrates the way CotD can be used, not only to understand the extent to which economic constraints may affect an individual’s or household’s diet, but also to develop tools, such as a recipe booklet, which can significantly improve maternal and child nutrition.