Developing a community-based nutrition surveillance system in Somalia

Mary Wamuyu is a nutritionist with four years’ experience in implementing nutrition in emergency projects in Kenya and a further five years in Somalia’s Gedo region. She holds a degree in Food, Nutrition and Dietetics and works as an Institutional Funding Officer for Trócaire Somalia.

Aden Mohamed is a member of the Ministry of Health District Health Office in Belet Hawa District and has worked as a health records officer for Belet Hawa hospital for nine years. He is also a trainer of trainers for the Community Based Nutrition Surveillance System.

Introduction

Somalia’s Gedo region is situated along its south-west border with Kenya and Ethiopia and comprises six districts (Belet Hawa, Dollow, Luuq, Baardheere, El Wak and Garbahareey). The population is largely pastoral and agro-pastoral; their livelihoods are often affected by cyclical droughts, which are common and increasing in severity. The region is home to over 734,126 people, including 168,000 internally displaced people (IDPs). Trócaire, an Irish NGO, operates in four of the seven districts, reaching approximately 225,000 people annually with interventions in health, nutrition, education and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), targeting IDPs as well as vulnerable and marginalised riverine and rural communities. The need for humanitarian assistance in Gedo is clear: acute malnutrition is 13-15 per cent, above the emergency threshold for the region and an estimated 13,260 children need ongoing and urgent treatment1.

Capturing data for effective programming

In conjunction with other partners, including government officials, Trócaire identified the need for a nutrition surveillance system that acts as an early warning system for early case detection and for identifying populations at risk of acute malnutrition. This led to the development of a simplified community-based nutrition surveillance system (CBNSS) to provide continuous trend monitoring of the nutrition situation rather than one-off surveys that only show prevalence levels at a particular point in time.

The CBNSS involves a random selection of villages (referred to as sentinel sites) that represent the catchment population and is using 30 such villages to monitor key trends in the following indicators:

- Global Acute Malnutrition or GAM (SAM+MAM) by mid-upper arm circumerferance (MUAC) and/or oedema;

- Diarrhoea, acute respiratory infections and fevers;

- Vitamin A and measles immunisation; and

- Household hunger scale.

Data collection is carried out every three months by trained community nutrition workers (CNWs), who are local residents. Prior to the data collection, the CNWs undergo a refresher training on data collection. Current spend on the CBNSS is US$5,000 per cycle, covering the need for CNW refresher trainings each quarter before data collection. This is expected to decrease to approximately US$4,000 per cycle.

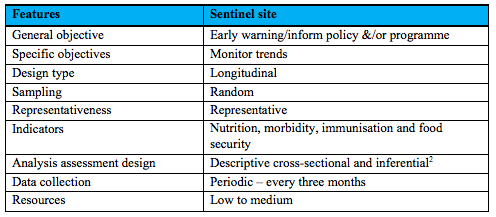

Table 1: Summary of features of the CBNS methodology

Changes to programme design

The 2017 CBNSS assessment had two main results, both of which called for a programme redesign: firstly, it revealed high levels of household food insecurity in all three districts; secondly, it identified the need for support in areas not previously targeted.

Food baskets were subsequently included in emergency interventions. The initial food basket contained rice, beans, oil and sugar. However, through community feedback, there was a request to include flour and to divide the 50 kgs of rice into 25kgs of rice and 25kgs of wheat flour; these recommendations were undertaken.

The response initially focused on IDPs in Luuq and Dollow. However, results from the CBNSS led to a retargeting and inclusion of beneficiaries in Belet Hawa, where little response had previously taken place, as well as increasing support for riverine communities in Dollow and Luuq. Trócaire has since secured funding to support this initiative.

Working with communities

The key implementing partners in all four districts include the community-appointed District Health Boards (DHBs) and Community Education Committees (local structures comprising of respected members of different clans within the district), and the Ministry of Health (MoH) District Health Officers. These structures are an effective, sustainable model for provision of services, particularly in a context where insecurity remains a challenge3.

The DHBs supported compilation of population data, mapping accessible/inaccessible areas and arranging community mobilisations (informing/gathering community members when surveillance was due). The MoH District Records Officers were trained as trainers of trainers (ToTs) and participated in the training of the CNWs for data collection and supervision. A technical team oversaw the process and disseminated the data to the programme team, community members, Nutrition Cluster partners in Gedo and other stakeholders. The focus is on a phased plan for establishing structures that provide direct oversight for health services with ongoing training to build capacity of local government officials.

Lessons learned

A number of aspects of the programme are working well, including buy-in from staff, government and the community, enabling implementation and the use of the data for decision-making and resource mobilisation. In addition, female CNWs have gone beyond the CBNSS, training women on MUAC screening in their own villages. More mothers are now aware of malnutrition, resulting in a notable increase in self-referrals (270 children over a six-month period).

CNW recruitment has been a challenge, partly due to literacy levels, although a translation of the tools into Somali, refresher trainings and supervision have improved capacity. Community expectations are high; some people feel left out due to the highly targeted nature of interventions and this requires continuous community sensitisation.

Experiences and lessons learned will be shared with stakeholders now that the one-year/four rounds of data collection are complete. Initial findings show that the system can be used to identify hotspots for malnutrition at a lower unit level (i.e. village level) than the FSNAU assessments can identify, as these are more general and less frequent (six-monthly compared to every three months). There are plans to advocate for CBNSS scale-up and integration into community nutrition programming (for example, livelihood and food security interventions) in light of the high GAM rates in South Central Somalia, including Gedo.

1FSNAU-FEWS-NET-2017-Post-Deyr-Technical-Release-29-January-2018.

2Use of a random sample of data taken from a population to describe and make inferences about the population.

3The Gedo region was operating without any government structures until 2015. Trócaire, in partnership with the DHBs, has been in charge of health service delivery in the bigger part of Gedo. With the new government in place, Trócaire is slowly shifting some responsibilities to the regional and district government offices in health and education with the aim of handing over fully to the government by 2021.