Nutrition budget analysis at national level: A contribution to a revised approach from West Africa

Adam Aho is Coordinator of the West African consultation on the methodology of nutrition budget analysis and has worked for three years with UNICEF West and Central Africa regional office.

Judith Kabore is an advocacy officer for Action Against Hunger, originally in Burkina Faso and then at the West and Central Africa regional office.

Seydou Ndiaye is National Coordinator of the African Network on the Right to Food and for Senegal’s Civil Society Alliance for the Scaling Up Nutrition Movement.

Dr Noel Zagre is Regional Nutrition Adviser for UNICEF West and Central Africa regional office.

Background

The importance of good nutrition for the health and economy of countries has been recognised for many years now, underlining the need for increased funding for the nutrition sector and the need to track financial resources dedicated to nutrition in national programmes. However, tracking nutrition financial resource flows is not straightforward, mostly due to their multi-sector nature. Although most nutrition-specific expenditures are incurred in the health sector, so-called nutrition-sensitive expenditures involve sectors responsible for water and sanitation, education, social protection, food and agriculture.

Nutrition financing and budget-tracking is generally recognised as a challenging process. In 2015 the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement developed a three-step approach to enable countries to assess resources dedicated to nutrition in their national budgets. The approach consists in first identifying budget-line items that are relevant to nutrition through a keyword search (a list of keywords is provided by the SUN Movement). Second, identified budget lines are classified into two categories: "nutrition-specific" and "nutrition-sensitive". Finally, a percentage is assigned to the amount of each budget line in order to estimate the concrete financing dedicated for improved nutrition outcomes1.

Nevertheless, seven countries in West Africa (Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Mauritania and Togo) that conducted a nutrition budget analysis in 2015 using this approach reported a number of issues, such as difficulties in identifying nutrition-relevant budget lines. Significant discrepancies were observed regarding the way each country categorised and weighted budget-line items.

Review of nutrition financing tracking in West Africa

In response to these issues, the regional offices of UNICEF and Action Contre la Faim (ACF) worked on a technical review of nutrition financing tracking in West Africa, consulting with governments, institutions and agency partner experts in the field2.

The main findings were:

- Importance of defining boundaries for nutrition programmes

Since nutrition problems require multi-sector approaches, many sectoral actions could be included in the budget allocation to the nutrition costed plan. Therefore, the consultation group deemed it important to clearly delineate between programmes within the nutrition sphere and those that are not. To do this, the consultation group recommends using the national common results frameworks (CRF), which lists nutrition-specific as well as nutrition-sensitive interventions. The CRF should also be based on nutrition determinants in the country and should be costed.

Although straightforward in theory, experience has shown the method of budget-line identification through keyword search to be challenging, since budget wordings are not often linked to nutrition documents and do not include nutrition terms. This is because the system of public finance management adopted by most countries in the region does not allow nutrition expenditure to be identified directly3. To address this, the consultation group recommends a line-by-line manual review of the national budget. Although lengthier than a simple keyword search, this would enable stakeholders to generate a comprehensive list of nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive government budget lines or programmes, in line with CRF4. This should be completed by both nutrition and budget experts (budget and planning staff from the ministry for budget/finance/economy and other key ministries, when needed). The group also recommends carrying out this step with additional interviews in order to clarify particular budget-line items, where identified.

- Classification of nutrition-related budget lines should not be systematic

The importance of the Lancet nutrition framework, as well as the continuum of care targeting the first 1,000 days (pregnant and lactating women and children under two years old) and women of reproductive age, including adolescent girls) was recognised by the consultation group for the categorisation step. However, it was agreed to use the Lancet nutrition framework as a reference or a guiding framework but not as the only mandatory framework. The use of the framework would allow identification of the determinants of malnutrition, but differentiate them by country and by regions in the same country.

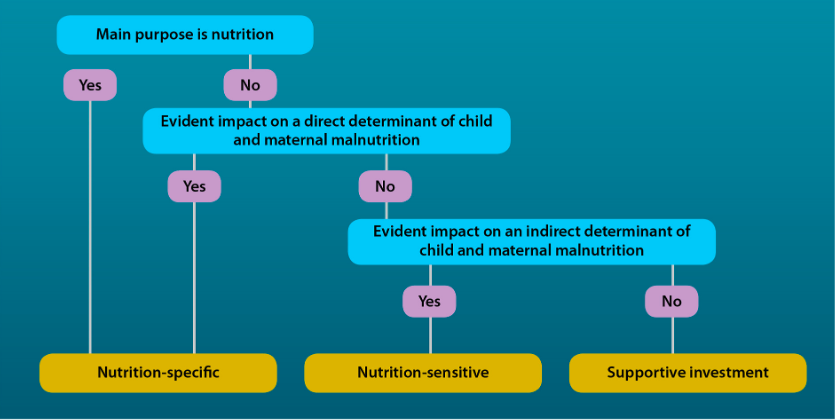

Two criteria are important in determining the classification of nutrition programme financing: (1) primary purpose and (2) expected outcomes on nutrition (direct or indirect impact)5. Nutrition-specific refers to high-impact interventions through which the nutrition outcomes are explicit. By contrast, nutrition-sensitive applies to programmes where the objectives or expected results are important to nutrition and may address the underlying determinants of malnutrition.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework for nutrition funding categorisation

The review proposes a third category, "supportive investment", to include broader development programmes that may contribute to improved nutrition outcomes but which have an extremely long and often unclear pathway, such as construction of roads in rural areas; irrigation programmes; the purchase of agricultural machines; research or training in nutrition, etc. This category is not considered in total nutrition allocations or expenditure.

- Arbitrary weighting cannot be avoided for nutrition-sensitive interventions for now but could be better conducted and harmonised

A comprehensive package of interventions combining nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive initiatives is required to tackle malnutrition. However, unlike nutrition-specific programmes, the impact of nutrition-sensitive interventions is less clear. For instance, women’s empowerment programmes usually focus on increasing female literacy, female income and female bargaining power in the household as their primary aims; therefore, it would be inaccurate to assume that 100% of the resources allocated to nutrition-sensitive interventions can be attributed to improving the nutrition situation in a country. Ideally, the weighting and level of funding for such interventions that should reasonably be included in the nutrition budget still needs to be developed scientifically to avoid relying on subjective judgment.

Since there is as yet no scientific method and no clear evidence on most nutrition-sensitive interventions, the consultation group suggests using the judgment of experts for this. The review’s advice was to use a weighting of 100% for nutrition-specific funding, which means the total amount will be taken into account. Regarding nutrition-sensitive funding, the group proposes a triple system of weighting (10%, 25% and 50%) to be applied to funding, depending on the estimated degree of nutrition sensitivity (low, medium and high respectively). In order to reduce the level of subjectivity, the following two criteria are to be considered: (1) expected outcomes (theoretical impact reflecting the literature, as well as the actual situation); and (2) targeted population (direct and indirect beneficiaries of a given action).

Piloting a consensual approach

In 2018 the methodology was applied in five West African countries: Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania and Togo. In all five countries the overall process was led by government (SUN Focal Points) in collaboration with partners and included capacity-development during the exercise to enable national stakeholders to undertake the exercise by themselves in the future.

As in previous experiences with the three-step approach, findings showed that budgets allocated to nutrition remain very low. Estimates for general government budget range from 0.1% in Guinea; 0.4% in Mali; 1.1% in Burkina Faso; 1.4% in Togo and 3% in Mauritania, although there is little financial commitment from governments for nutrition, despite the precarious malnutrition situation in all five countries. Moreover, in line with other similar exercises, most of the financing was found to be engaged in nutrition-sensitive actions; Guinea has no budget allocation for nutrition-specific activities, while Burkina Faso has the highest contribution at 14%. Findings also show that significant nutrition-sensitive budgets are invested in agriculture (Guinea and Mali), health (Burkina Faso), social protection (Mauritania) and water, sanitations and hygiene (Togo). Reasons for this skewing of investment toward nutrition-sensitive interventions are unclear and the issue requires further investigation.

Challenges encountered

Two main obstacles were faced in conducting nutrition budget-tracking by applying the consensual methodology. Firstly, CRFs do not exist in some of the countries (for example, Guinea and Togo). Thus, a list of interventions was developed based on the determinants of malnutrition in the country and validated by all nutrition stakeholders, to be used as a reference to identify nutrition budget lines. Secondly, the level of budget detail is very low in most of the public finance management systems being used by countries in this review. This meant that in-depth analysis of each identified budget line (activities, objectives, expected results, beneficiaries) was instead performed through interviews with resource people in the relevant ministries that were familiar with particular programmes and budgets. Advocacy is recommended to push for programme-based budgets that would better enable identifying nutrition-relevant budget lines.

Lessons learned and next steps

A number of key lessons were learned from this initiative:

- There is a great need for further actions and breakthrough strategy for increased domestic budget for nutrition, especially for nutrition-specific investments. Furthermore, nutrition-sensitive programmes should be better designed and oriented to improve nutrition outcomes;

- Government ownership and leadership are critical to successful budget analysis;

- Nutrition budget-tracking should be conducted routinely (yearly): there is a need to strengthen the methodology and to develop in-country capacity for the analysis;

- Adequate timing for the exercise is important to better influence budget process: for most West African countries, this would be between February and June;

- Involving a wide range of stakeholders increases buy-in and the quality of the analysis;

- It is important to track external funding for nutrition in the analysis, so a separate exercise should be conducted to cover external funding that bypasses national budgets.

The findings, interpretations and conclusions in this article are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of UNICEF or ACF, their executive directors, or the countries that they represent and should not be attributed to them.

Footnotes

1http://scalingupnutrition.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/SUN-Budget-Analysis-Short-Synthesis-Report-SUNGG-version-EN.pdf

2www.actioncontrelafaim.org/publication/investir-dans-la-nutrition-cest-sauver-la-vie-de-28-millions-denfants-souffrant-de-malnutrition-chronique/

3Expenditures are configured by administrative classification (i.e., the department or unit under which the expenditure falls) or economic classification (i.e., the nature of expenditure such as personnel costs, recurrent or capital expenditure).

4The time taken to complete the keyword search depends on the length of the national budget; among the five countries it took 2.5 days on average and covered four to five fiscal years.

5Direct and indirect determinants refer respectively to direct/immediate and underlying/structural factors or causes of child and maternal malnutrition.