Putting communities at the heart of improving nutrition: Experiences from Bénin

Professor Roch Mongbo is Chief Executive of the Food and Nutrition Council of the Republic of Bénin (CAN-Bénin) and the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement country Focal Point.

Minakpon Stanislas Hounkanlin is Director of Advocacy for the Bénin National Association of Municipalities, where he has coordinated technical support on nutrition advocacy, including working with the Food and Nutrition Council.

Ophélie Hémonin is a policy advisor in the SUN Movement Secretariat, where she supports a portfolio of 10 francophone African countries in stepping up efforts to reach their nutrition targets.

This article draws on the findings from stakeholder interviews carried out in Bénin as part of an in-depth country review (‘Deep Dive’) to support the mid-term review of the SUN Movement. The final report will be available on the SUN Movement website shortly.

Introduction

When Bénin joined the Scaling up Nutrition (SUN) Movement as an ‘early-riser’ country in 2011, the time was ripe for strong political commitment to tackle malnutrition. In spite of encouraging economic growth rates and a stable political climate, more than half of the population live on less than USD1.25 a day, with 44.6% of children under five years old (CU5) estimated to be stunted and 12% wasted1. As of 2018, the national prevalence of CU5 stunting has decreased to 32.2% (still greater than the developing country average of 25%), CU5 wasting prevalence is down to 5% (less than the developing country average of 8.9%) and exclusive breastfeeding rates are up from 32% to 41.6%1. However, Bénin is not on course to meet the World Health Assembly 2025 global targets for all indicators analysed with adequate data, although it performs relatively well against other developing countries1.

Developing community nutrition

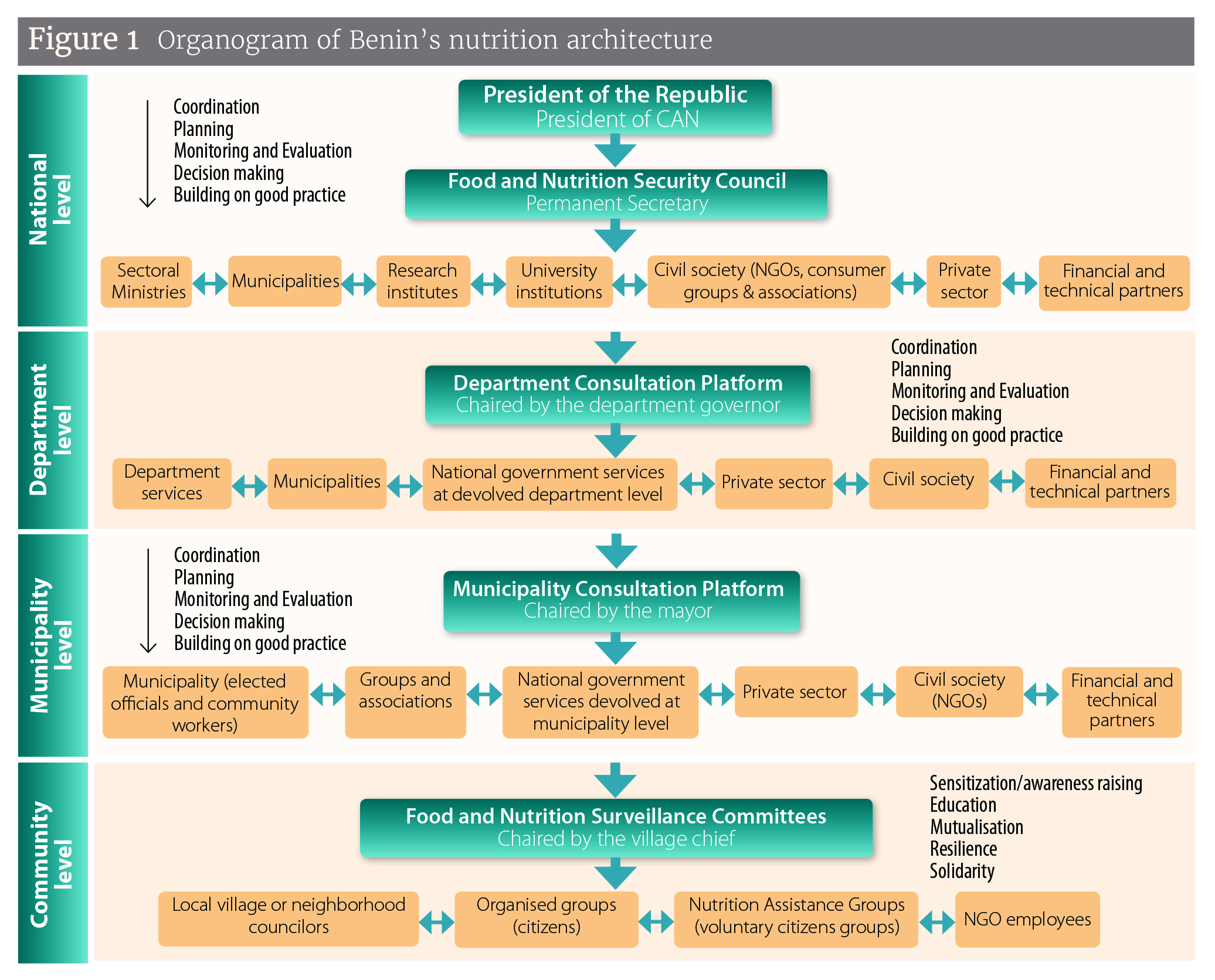

Even before joining the SUN Movement, Bénin had put in place strategies and institutional arrangements to reduce malnutrition. A multi-sector and multi-stakeholder body, the Conseil de l’Alimentation et de la Nutrition (CAN), was created in 2009 and housed within the Office of the President. The CAN Permanent Secretary (SP-CAN) acts as the SUN Focal Point. In the same year, the 10-year Strategic Food and Nutrition Development Plan (PSDAN) was launched; this considers communities a cornerstone of its implementation. The Community Nutrition Programme (PNC), an innovative project driving the PSDAN’s nutrition-specific section of interventions in 10 pilot communes, was a key component.

In 2014, learnings from the PNC were scaled up with the large Multisector Health, Food and Nutrition Programme (PMSAN). Funded with a USD28 million loan from the World Bank, PMSAN is focused on the prevention and treatment of malnutrition in 40 of Bénin’s 77 communes2, including the 10 PNC communes.

Communal Consultation Frameworks

In each commune the institutional framework to implement the programme is provided by the Cadre Communal de Concertation (CCC), or Communal Consultation Frameworks for nutrition, created by municipal decree and chaired by the commune’s mayor. CCC meetings provide a platform where the municipal team, local representatives of the Ministries of Social Affairs, Agriculture, Health and Education, and citizen groups such as women’s associations and non-government organisations (NGOs), meet on a quarterly basis and share information on their respective workplans and interventions, bottlenecks and progress. Together they coordinate and plan interventions to be carried out by an implementing NGO (selected through a call for tender), which leads on the monitoring of nutrition-related sector indicators and reports to the SP-CAN. By November 2016, all 40 communes of the PMSAN had set up their communal frameworks.

Involving nutrition-sensitive sectors and promoting a rights-based approach

Social protection is one of the most decentralised sectors in Bénin. Centres for Social Promotion (CPS), of which there is at least one per commune, were originally set up to oversee the implementation of the policies and strategies of the Ministry of Social Affairs and support community development at the grassroots level, including nutrition-promotion activities. Nowadays, and through the promotion of the Rights of Children and the Family Code, the centres organise social mobilisation sessions on various topics with a focus on women, children and vulnerable groups. For example, in the Adja-Ouèrè commune, which borders Nigeria in the southeast of Benin, social protection centre staff, in conjunction with the NGO, conduct weekly screening sessions for detecting children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and refer them to municipal and hospital treatment centres.

Accelerating impact through decentralised nutrition coordination

As part of the PMSAN, Food and Nutrition Surveillance Committees (CSAN) and Nutrition Assistance Groups (GAN) were set up, comprising volunteers chosen by communities for each village and for every 10 households respectively, to track children suffering from acute malnutrition (both severe and moderate), as well as provide support via social and behaviour-change education for prevention. Over a few years, community participants in Adja-Ouèrè progressed from meeting to share updates on interventions to working together on joint planning, implementation, monitoring and reporting.

Making nutrition everyone’s business

Successful local nutrition coordination appears to be boosted in communes where the mayor ensures that nutrition is ‘everyone’s business’. In Adja-Ouèrè, the mayor set an example by reaching out to chefs d’arrondisssement (heads of districts) and village and urban neighbourhood chiefs to discuss nutrition, involve them in efforts and turn them into nutrition champions. With such leadership, participants’ ownership in the citizens group increased over time. Although the responsibility for delivering the PMASN theoretically relied solely on the implementing NGO, members started reporting on interventions and organising joint delegations to visit vulnerable families. Adja-Ouèrè’s progress, acknowledged by an award in 2014, created a positive ‘domino effect’ among communes of Plateau Department that led to more coordination, better coverage of malnutrition screening activities, and a higher number of children referred and treated for SAM (according to stakeholders interviewed for the ‘Deep Dive’ case study).

Mobilising the mayors

In Bénin, mayors are incentivised through two channels: the Bénin National Association of Communes, which is a fully-fledged member of the CAN multi-stakeholder platform for nutrition, and the SP-CAN. The latter organised a sensitisation campaign involving the department governors (préfets) and recruited six regional coordinators to support them in steering and coordinating communal and departmental levels, and reporting to the central level. This proved a winning strategy, with governors ensuring that all local development plans include a nutrition budget line and that local representatives of ministries include nutrition in their workplans. One former mayor and governor of Couffo Department was even nominated Bénin’s nutrition champion for his outstanding promotion of nutrition, and the governor of Plateau Department presented the Department’s progress in moving “from national vision to local implementation” at the 2019 SUN Global Gathering in Nepal.

Beginning in December 2018, each of the 77 communes has developed a common results framework listing targets, costed interventions, roles and responsibilities, and timelines. No local development plan can be validated in any commune if it does not include a dedicated nutrition budget line; a crucial milestone in community prioritisation of nutrition. This has enabled communes to self-fundraise; so far, 25 communes in nine departments have direct partnership agreements with German development agency GIZ. The CAN has finalised its National Nutrition Policy (2020-2030) and is now finalising the strategic multi-sector nutrition plan (the national-level common results framework), which has been based on all the municipality-level plans – a truly bottom-up approach!

Challenges for nutrition budgeting

Joint funding of the action plans, however, remains a challenge, as is maintaining continuity and political momentum in spite of political cycles. With the notable exception of the education sector (school feeding coverage has increased from 31% to 51% in 2019) and the social affairs sector, fewer ministries in the administration elected in 2016 appear to be prioritising and budgeting nutrition interventions in their current programmes. However, a minimum functioning budget remains crucial in a context where much of the implementation relies on the motivation of community workers, who are often working on a voluntary basis and within a weak infrastructure. A three-track approach, consisting of advocating for the government bodies supporting the decentralisation processes to include a nutrition line; fundraising with external partners to directly support local development plans involving nutrition actions; and more actively engaging the private sector locally could be the way forward.

Findings from the in-depth country review concluded that increasing political will and leadership – for instance, through greater presidential ownership of CAN and substantial public-resource allocation – may be key to providing local platforms with the necessary means of implementation and enabling them to overcome local political obstacles. Galvanising mayoral commitment is also important in resolving barriers to progress, such as traditional distrust of ‘modern’ treatment centres and hospitals and food taboos, and in encouraging local partnerships with the private sector to build more nutrition-sensitive food systems. Given their important role, better coordination, inclusion and representation of local civil society organisations involved in the delivery of the communal nutrition action plans in the CAN may also offer opportunities for convergence and higher impact.

Footnotes

1 https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/western-africa/benin/#profile

2 The departments of Benin are sub-divided into 77 communes, which are divided into arrondissements, themselves divided into villages or city districts. The number of villages per commune varies.