Meeting the health and nutrition needs of adolescents and youth in Ethiopia

Meseret Zelalem is a paediatrician and Director of the Maternal and Child Health Directorate of the Ministry of Health. She also has 10 years’ experience in supervising and mentoring residents and community services engaged in school health and outreach programmes.

Sisay Sinamo is a medical doctor working with Ethiopia’s Seqota Declaration (SD) Federal Programme Delivery Unit at the Ministry of Health, where he is leading the SD innovation phase. He has over 18 years’ experience of international public health and nutrition.

Yetayesh Maru is a public health nutrition specialist currently working for UNICEF Ethiopia with more than 16 years’ experience in development and emergency nutrition programmes, research and evaluation.

Introduction

Ethiopia has a large number of adolescents (15-19 years old) and youth (20-24 years old), which together account for nearly 22% of the population1. This young population is an enormous intellectual and economic resource for the country and their needs have implications for Ethiopia’s social, economic and political agenda as it places demands on the provision of health services, education, water and sanitation, housing and employment.

The Government of Ethiopia has a range of programmes and strategies to improve the health and nutrition of adolescents and youth. These include the National Nutrition Programme (2016-2020), the School Health and Nutrition Strategy (2014), the School Health and Nutrition Programme (2017), the Seqota Declaration (2015-2030) and the National Adolescent and Youth Health Strategy (2016-2020)2.

Adolescent health and nutrition issues

The period of adolescence and youth is characterised by intense physical growth and high nutrient needs, during which adolescents gain up to 50% of their adult weight and skeletal mass and up to 20% of their adult height, while female adolescents need to replace loss of iron through menstruation3. Adolescence is also seen as a ‘second window of opportunity’ to break the intergenerational cycle of malnutrition; for example, through improving adolescent girls’ nutrition and delaying pregnancy.

A 2019 review of the current status of female adolescents and youth in Ethiopia presents a very worrying picture. It shows that 13% of the 15-19 female population began child bearing, 3% of these gave birth by the age of 15 and 21% by the age of 184. The percentage of adolescents who died from pregnancy-related deaths during pregnancy, delivery and the two months following delivery was 17% in 20162, and the majority of young women who married in childhood gave birth before they completed their adolescence. These young women were less likely to receive skilled care during pregnancy and delivery and this is estimated to contribute to one in five adolescent girl deaths and a 50% increase in neonatal mortality. Adolescent pregnancies are also more likely to result in premature and low birth-weight babies, who are more vulnerable to neonatal death, malnutrition and infection.

Furthermore, 29% of adolescents are chronically undernourished, 3% are overweight or obese and about 20% of girls are anaemic5, while 28% of girls consumed less than three meals per day6. Today, at least 51% of 14-19-year-olds are suffering from the effects of stunting during childhood. Moreover, neural-tube defects in newborns are becoming an increasing problem as a result of nutritional, maternal and environmental factors.

Adolescent boys are also malnourished with an estimated 59% having a low body mass index (BMI < 18.5) and 18% are anaemic5. Ethiopia has one of the highest burdens of neglected tropical diseases in the world, with over 10 million children at risk of schistosomiasis and 18 million children at risk of soil-transmitted helminths (parasitic worms). Of the country’s 833 districts, intestinal worms are endemic in 741. These helminths affect youth and adolescents’ health, causing malnourishment, anaemia and impairment of mental and physical development.

In Ethiopia, adolescents’ reasons for leaving school differ by sex and rural/urban residence. The main reason cited by girls was early marriage (29% for urban and 40% rural)7. Ensuring good health and nutrition provision when children are of school age can boost attendance and educational achievement.

Factors affecting adolescent health and nutrition

The major factors that affect adolescent boys and girls nutrition status are related to the external environment, such as lack of access to basic adolescent health and nutrition services, lack of access to food in general, and a gradual increase in access to and utilisation of fast-food outlets (such as school tuck-shops, food stores and vendors). Individual factors, such as psychological and biological circumstances, drive certain behaviours; family factors such as parental food preferences and the social environment (including peer pressure and community perceptions) also have a strong role.

Ethiopian adolescent and youth health and nutrition strategy

The National Adolescent and Youth Health Strategic Plan (AYHS) (2016-2020) sets out the priority health and nutrition needs and challenges faced by adolescents and youth in Ethiopia. The strategy addresses physical activity as well as reproductive health, HIV, substance use, mental health, nutrition-related chronic diseases, injuries, gender-based violence and harmful traditional practices. Activities are focused on improving dietary diversity and offering nutrition counselling and screening (via school health and nutrition clubs and youth-friendly health facilities), anaemia prevention and treatment (weekly iron-folic acid supplementation), menstrual hygiene management, deworming and increasing physical activity (youth-friendly school playgrounds with tennis, volleyball and football facilities).

Delivery platforms

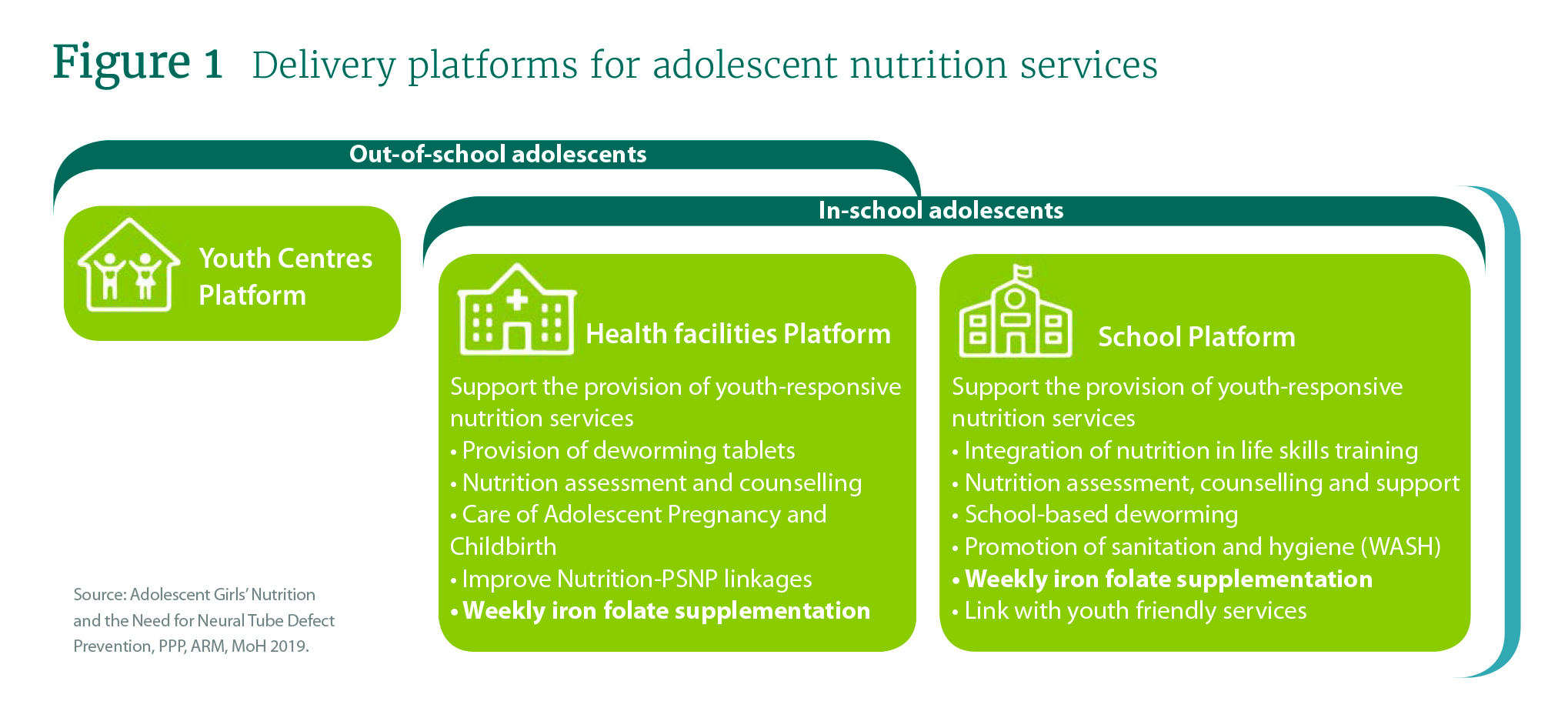

About 90% of Ethiopia’s adolescent population attend school and these are the primary platforms for providing adolescent-friendly health and nutrition services (see Figure 1). There are also ongoing efforts to make health facilities ‘youth friendly’ for out-of-school interventions and over 2,000 government-built youth centres. Specially trained health education workers are providing services in some regions; both in schools and at the youth centres.

• Out-of-school adolescent platforms comprise youth centres and health facilities. Youth centres are used for skills development, while health facilities provide youth-responsive nutrition services (see Figure 1)

• In-school adolescent platforms provide support for the provision of youth-responsive nutrition services (see Figure 1).

Challenges and lessons learned

Various challenges have been encountered in effective implementation of the AYHS. They include: lack of a dedicated coordination mechanism among implementing sectors and partners; high turnover of trained personnel; low stakeholder participation; inadequate financial, human and logistical resources allocation; lack of age- and sex-disaggregated data; socio-cultural barriers around adolescent and youth health and nutrition; lack of integration into the education curriculum; and inadequate youth involvement. In this regard, the government has also developed mitigation strategies to reduce the impact of these challenges, such as development of a technical working group and creating structures in implementing sector ministries to oversee the adolescent health strategy; increasing public awareness; mentorship for continuation of school and livelihood training for out-of-school youth; and mobilising youth to take an active role in their health and nutrition issues.

Footnotes

1 https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/ethiopia-population/

3 World Health Organization (2005). Nutrition in adolescence issues and challenges for the health.

4 Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF. 2019. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Key Indicators. Rockville, Maryland, USA: EPHI and ICF. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/PR120/PR120.pdf

5 EDHS (2016) report https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR328/FR328.pdf

6 In-School Adolescent Girls’ Nutrition Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (KAP) Survey in Somali, Gambella, SNNP and Oromia Regions, Ethiopia. UNICEF (2016)

7 Ethiopia Young Adult Survey (2009)