Measuring coverage of acute malnutrition treatment at the national level in Mali

Summary of Field Exchange 49 article by Sophie Woodhead, Jose Luis Alvarez Moran, Anne Leavens, Modibo Traore, Anna Horner, Saul Guerrero.

In 2014, the Mali Ministry of Health, UNICEF and the UK-based Coverage Monitoring Network (CMN) implemented a national scale assessment of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) treatment coverage (referred to as SLEAC) in Mali. The number of SAM cases admitted and treated in the integrated management of acute malnutrition (IMAM) programme in Mali has increased steadily since 2011. There was a need to evaluate levels of access against levels of need and to identify the barriers to access in order to learn lessons and improve services.

In 2014, the Mali Ministry of Health, UNICEF and the UK-based Coverage Monitoring Network (CMN) implemented a national scale assessment of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) treatment coverage (referred to as SLEAC) in Mali. The number of SAM cases admitted and treated in the integrated management of acute malnutrition (IMAM) programme in Mali has increased steadily since 2011. There was a need to evaluate levels of access against levels of need and to identify the barriers to access in order to learn lessons and improve services.

The survey was conducted from April to June 2014 across seven of nine regions in Mali (Kidal and Gao regions were omitted due to security conditions). The survey provided a detailed visual representation of treatment coverage, with information at the ‘Cercle’ level (the sub-regional administrative division). SLEAC was selected as the most appropriate survey method, as it is designed to estimate programme coverage over wide areas. The survey was planned and jointly implemented by CMN, UNICEF and national counterparts, including the Ministry of Health (MoH), and The National Institute of Statistics.

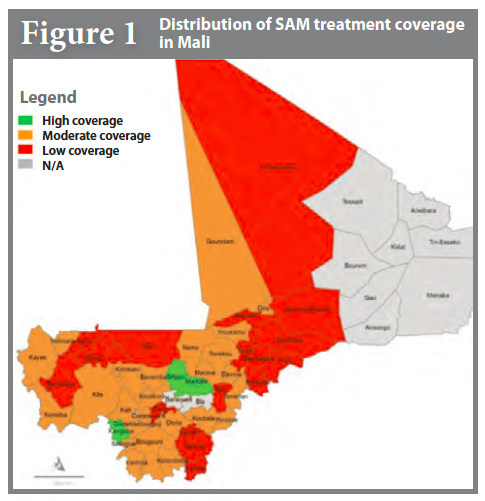

Based on a three tier classification of high coverage (>50%), moderate coverage (between 20% and 50%), and low coverage (<20%), the survey found that 4% (n=2) of the 48 assessed Cercles had high coverage, 46% (n=22) had moderate coverage and 33% (n=16) had low coverage. Coverage estimations could not be made for eight of the 48 surveyed Cercles because of low sample sizes. Figure 1 demonstrates the spatial spread of coverage. The overall point coverage level was estimated at 22.3% (95% CI = 16.7%, 27.6%).

Interviews were conducted with 894 carers of children who should have been admitted for treatment but were not enrolled to better understand barriers to access. Lack of awareness about malnutrition, followed by lack of awareness of the programme, were the reasons most frequently reported for non-enrolment. One third of carers (33%, 302/894) did not consider their child sick and amongst those that did, over half (53%, 316/592) did not consider their child malnourished. Amongst those that recognised their child was malnourished, half (50%, n=138/276) did not know where their child could be treated. Among those who knew their child was sick or malnourished and knew where to find treatment (n=138), major reasons for non-enrolment were distance to the health facility (n=31) and lack of money (n=21). In rural settings, median distance to travel to the nearest health facility varied from 7.5km to 15.5km.

Factors related to the organisation and quality of the programme also influenced the high rates of non-attendance. These included admission and discharge criteria leading to rejection, therapeutic food shortages, and lack of information provided to beneficiaries.

Results have provided clear recommendations that have since enabled the MoH to take decisive action to improve access to SAM services in Mali.