Mobile clinics as a strategy to identify and treat children with acute malnutrition in difficult-to-reach areas in Chad: A case study of the Wadi Fira Region

Dahab Manoufi is an economist and manages the NGO Bureau d’Appui Santé et Environnement (Health and Environment Support Bureau), Chad.

Dahab Manoufi is an economist and manages the NGO Bureau d’Appui Santé et Environnement (Health and Environment Support Bureau), Chad.

Dr Hervé Oufalba Mounone is a doctor and coordinator at the NGO Bureau d’Appui Santé et Environnement (Health and Environment Support Bureau), Chad.

Background

Like most countries in the Sahelian belt in Africa, Chad experiences high levels of acute malnutrition (often referred to as wasting) which regularly exceed emergency thresholds of 15%. Acute malnutrition rates in Chad have remained consistently high over the last ten years and levels of stunting have increased from 28% to 39%. Almost one in five babies is born with low birth weight, and only three per cent of women practise exclusive breastfeeding.

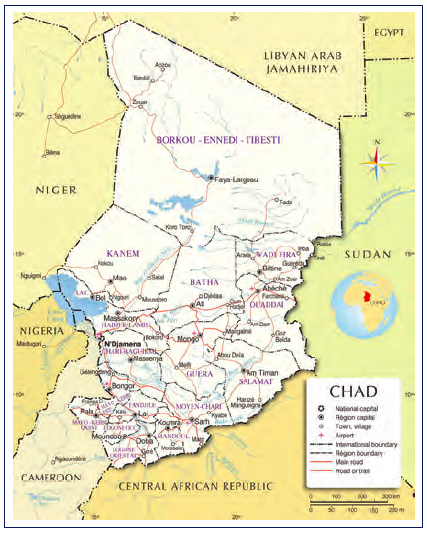

Rates of acute malnutrition are even worse in the populations living in difficult-to-access areas, such as the Wadi Fira Region, situated on the far eastern side of Chad.1

The causes of malnutrition in Wadi Fira are multiple, but key are the barriers to accessing health services due to low population density, the long distances that separate villages from healthcare facilities, and insufficient staff in quantity and quality. Added to this is the restricted mobility of household members caused by high poverty levels, which means households have to dedicate their time to subsistence livelihoods, and where women lack decision-making power.

This article describes how mobile health clinics with nutrition outreach activities were supported in one of the most difficult-to-access areas in Chad.

Nutrition surveys carried out between 2010 and 2015 have revealed high levels of acute malnutrition in the eastern Chad provinces (at times rates have been close to 25%), and a high caseload of children under five years of age in need of immediate treatment of the severest form of acute malnutrition. In response to this, BASE (the Health and Environment Support Bureau), a non-government organisation, initiated a community nutrition and health project in 2011. The strategy was to implement mobile clinics for hard-to-reach populations who do not benefit from fixed-point health services. With financial support from UNICEF and the WFP the project, initially planned for a year, has twice been renewed and covered the three districts of the Region until December 2014.

Mobile clinic activities

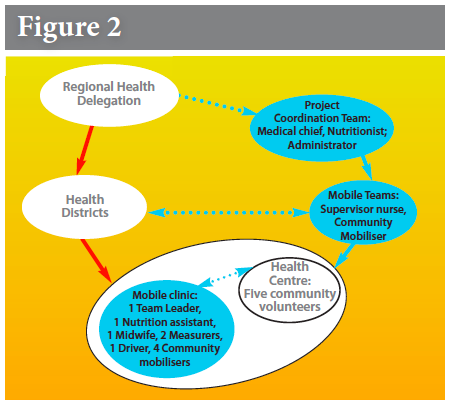

Priority was given to villages located over 5km from a health centre that were difficult to access due to limited means or terrain. Figure 2 shows the implementation of the activities in the three districts.

Mobile team nutrition activities were overseen at the Regional Health Delegation headquarters by a team of three health staff: a medical chief officer (médecin chef de projet); a nutritionist in charge of all training activities and supervision of the application of the national nutritional protocol of management of acute malnutrition; and an administrative/financial assistant.

At the Health District level, six mobile teams were formed, made up of two nurses, a midwife and two measurement officers. These teams were organised to support the health staff responsible for the health centres in 47 sites covering all three health districts. Each Health District had a nurse supervisor and a community mobiliser who tookon the logistics, monitoring and data collection activities relating to the work of the mobile teams as per the implementation of the joint quarterly plans set out by the District Level Management team (Equipe Cadre de District).

The activities carried out by the mobile team included measurement of mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) for screening for cases of acute malnutrition and arranging for severe and complicated cases to be referred to the therapeutic nutritional units (unité de nutrition thérapeutique) in the district hospitals (in Biltine and Iriba). Transportation was provided from the mobile clinics for patients referred to the hospital and their return home once they had recovered.

Community involvement was ensured through four to six community mobilisers per village who supported screening activities, looking for defaulters and making home visits for children who were not gaining weight. They were also involved in supporting the health mobilisers and nurses in their sensitisation activities around basic household-level practices.

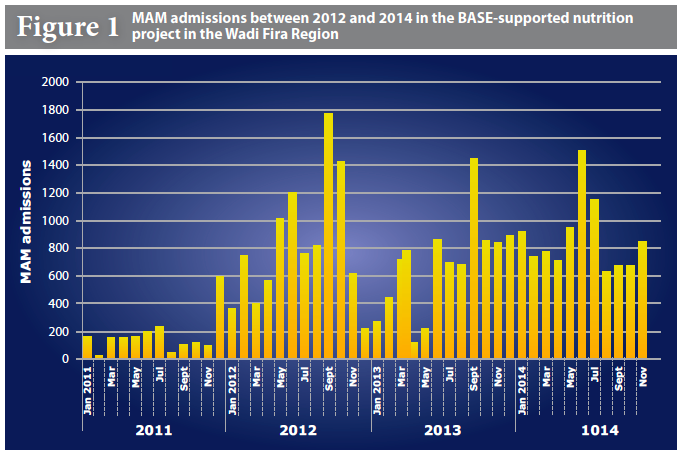

In January 2011, the number of children being admitted for the treatment of moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) based on a MUAC of 115-125mm in Wadi Fira was 200. Treatment for MAM includes the use of a supplementary, ready-to-eat food supplied by WFP that promotes weight gain. When the BASE nutrition project activities began in October 2011 this number started increasing, as shown in Figure 1 below, with over 10,000 treated during 2014. This increased the number of children being treated for MAM considerably during the project in a remote area of Chad where the national coverage rates for MAM are estimated at less than 15%. Seasonal variations in rates of acute malnutrition were reflected in the admissions patterns, as was the drop in the number of children admitted in April and May 2013, which corresponds to a project funding gap when mobile teams were not operating. (Note: these figures are representative of the BASE-supported project areas only.)

The BASE project admissions data presented above reflects a very low number of admissions at the start of the project in 2011 and then a steady increase over 2012, which was a year of crisis due to drought in the Sahel. The number of admissions continues to be relatively constant after June 2012, suggesting that outreach activities using the mobile clinics may have contributed to increased attendance at a time when prevalence levels of acute malnutrition would be expected to rise during the lean season (May to October), but admissions have been fairly regular3.

Lessons learnt

The involvement of communities, the provision of transport for referred children (and their carers) and food assistance are key factors that helped mothers to accept the referral of their children to the hospitals. On the other hand, the cost of implementation, the lack of integration with other services and an unreliable supply chain of supplementary, ready-to use foods limited the scaling-up of such an approach by the health authorities.

Even though this project allowed children suffering from different degrees of acute malnutrition to be referred and treated, it was not focused on preventative actions that could have further reduced the prevalence of acute malnutrition in this population. Acute malnutrition in Chad is still too often perceived as a short-term problem and not a structural one.

References

1 INSEED. Nutritional study 2010.

2 BASE 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014 activity reports.

3 UNICEF. Report on the Sahel nutritional study. 2014.

English

English Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch Italiano

Italiano Español

Español