Shaping national food and nutrition policy in Nigeria

Ambarka Youssoufane, ENN’s West Africa Regional Knowledge Management Specialist, interviewed Roselyn Gabriel, Deputy Director of Food and Nutrition, Ministry of Budget and National Planning, on the process of developing Nigeria’s National Food and Nutrition Policy.

Roselyn Gabriel has worked in the field of nutrition for the past 30 years at the national level, supervised and monitored state-level programming on Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM), and advocated at the community level to increase knowledge and understanding of nutrition. She holds an MSc in Public Health.

Background

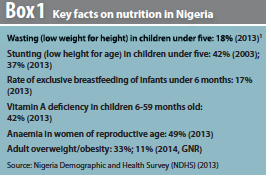

Nigeria is a country with abundant natural and human resources, but poverty remains pervasive. Children from poorer households are four times more likely to be malnourished than children from wealthier families, and the country has the highest number of children under five who are stunted (low height for age) in sub-Saharan Africa and very high levels of wasting (see Box 1). As with other low and middle-income countries (LMICs), Nigeria is also facing the double burden of malnutrition, with the co-existence of undernutrition and overweight/obesity at both household and community levels.

In response to the urgent need to scale up high-impact and cost-effective nutrition interventions, in April 2016 Nigeria adopted a new National Food and Nutrition Policy (NFNP) that reflects emerging issues such as the importance of the first 1,000 days and the upsurge in the prevalence of diet- related, non-communicable diseases (NCDs). The process of developing the new policy has been a lengthy one, involving multiple stakeholders (including the Ministry of Health and State Nutrition Offices) driven by the Ministry of Budget and National Planning and supported by development partners and non-governmental actors.

The new NFNP has been commended for its SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-limited) targets for the reduction of stunting and wasting, for being costed and for identifying current resource allocations and resource mobilisation.

1. The new policy is a significant achievement. How did it come about?

The impetus to review the policy came from Demographic Health Survey (DHS) results in 2013, which revealed very high levels of wasting of about 18%, high levels of stunting, and specific micronutrients deficiencies such as Vitamin A, anaemia and iodine. The Ministry of Budget and National Planning initiated a committee with relevant stakeholders to review the former 2001 nutrition policy, which served as an initial draft. This original policy had become outdated due to poor implementation, inadequate funding and ineffective coordination. It also didn’t take account of emerging initiatives, namely the birth of the SUN Movement (Nigeria joined in 2011), the rise of NCDs and the 1,000 days concept.

Three different sets of meetings were organised to ensure maximum ownership: state level meetings in the country’s three regions (south, east and north); technical meetings at national level; and validation meetings with all national commissioners. The policy was launched by the First Lady, showing commitment at the highest level, and all 36 Nigerian States are ‘domesticating’ the nutrition policy; that is, adapting the national nutrition policy to the state-specific context. Each state is therefore elaborating its own action plan derived from the policy.

2. Did you seek outside guidance or use other country examples for policy development?

Many partners were involved, including the Ministries Departments and Agencies, the UN agencies, academics etc., bringing different knowledge and experiences to the process. Technical assistance was also provided by UNICEF through the recruitment of consultants, who gave technical support and expertise for the regional and national consultations of stakeholders, elaboration of different drafts, and integrating comments from various participants.

3. What are the main priorities of Nigeria’s food and nutrition policy?

The goal of the new NFNP is to attain optimal nutritional status for all Nigerians by 2024, with an emphasis on vulnerable groups such as infants and children, adolescents, women of reproductive age and people in difficult circumstances (e.g. those living with HIV/AIDs and internally displaced people). There is also recognition of the need to prevent and control NCDs and the importance of incorporating food and nutrition considerations into development plans at federal, state and local government level.

The NFNP key targets have been set according to the World Health Assembly (WHA) Global targets 20252 and include:

- Reduce stunting rate among under-five children from 37% in 2013 to 18% by 2025;

- Reduce childhood wasting, including Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) from 18% in 2013 to 10% in 2025 [the WHA target is to reduce to wasting to 5%];

- Reduce anaemia among pregnant women from 67% in 2013 to 33% in 2025;

- Increase exclusive breastfeeding rate from 17% in 2013 to 65% by 2025; and

- Halt the increase in obesity prevalence in adolescents and adults by 2025.

There are several other targets that involve increasing coverage of interventions such as universal household access to iodised salt, zinc supplementation in diarrhoea management, proportion of children who receive deworming tablets and coverage of Vitamin A supplementation.

4. Has the new policy been budgeted? What was the process for costing and what proportion is to be funded by the government and development partners?

After the policy development phase, nutrition stakeholders developed a costed action plan with the support of the Micronutrient Initiative (now Nutrition International), who provided technical assistance to support the process. The 2001 NFNP suffered from the lack of a specific budget line, which blocked the implementation of nutrition activities. That is why the Federal Government has called for specific budget lines to fund the action plan. The President has directed relevant ministries to create specific budget lines to fund nutrition activities based on the NFNP. The 2017 national budget was supposed to make these provisions.

However, discussions are still ongoing with different ministries to comply with presidential instructions. Even though it is difficult to clearly evaluate the limit of the budget created through domestic funding at this stage, we are confident that this mechanism, combined with external donor funding, will allow the scale-up of nutrition interventions to achieve the policy’s objectives.

5. How does the policy relate to the federal governments?

The policy covers multi-sector areas and is therefore amenable to challenges in the course of addressing malnutrition issues. Indeed, although we know the nutrition challenges are high, we also know that they are unevenly distributed across the country. So, the states are in the process of domesticating the policy by developing their own specific action plan emphasising the local context. The state’s action plan is going to be costed and used for advocacy for funding at state government level, ensuring better alignment and coordination with the NFNP. The national action plan will also take into consideration the different sectors involved and develop specific strategies and activities for each sector.

6. What were the most important challenges in writing and adopting the policy?

One of the important challenges we faced was convening meetings with all the stakeholders, particularly when the country has been facing a serious nutrition emergency in the north-east due to the Boko Haram crisis. This has diverted considerable government efforts, including nutrition expertise. There was also a challenge in finding funding for meetings, but various partners started expressing interest in the process and the government also provided some funding.

When the policy document was completed, obtaining the support of the Federal Government was particularly challenging, since there was a new administration after the 2015 general elections. It took us time to brief the new administration about the policy and we had to wait until the government was fully operational before introducing the document. This was done through the National Council of Nutrition (NCN), which is chaired by the Vice President and is the highest decision-making body for nutrition. The NFNP was one of the first documents to be attended to by the new administration.

7. Finally, what advice would you give to other country governments in the region that might want to follow Nigeria’s example?

One of the key lessons we learnt is the importance of working with all stakeholders from government and nongovernment agencies, civil society, even the business sector should be invited to the table. Given that nutrition requires multi-sector interventions to have greater impact, working with all relevant stakeholders right from the policy development step is the only way to be effective and ensure maximum acceptance and understanding. In Nigeria, the SUN Movement has been playing an effective role in bringing people together around the SUN Focal Point, who sits in the Ministry of Health, with the National Committee on Food and Nutrition (NCFN) playing the role of government networker. Today there is a very high commitment toward nutrition at the global level and we are confident that the new policy will help address the issue of malnutrition in line with these global targets and initiatives.

1 Rates of wasting tend to ‘surge’ seasonally during the year and will be higher if a survey is conducted during the lean season. For example, the Global Nutrition Report Nigeria country profile (2015) estimates SAM at 8%: http://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/129994/filename/130205.pdf

2 www.who.int/nutrition/global-target-2025/en/